Nicholas Hilliard facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Nicholas Hilliard

|

|

|---|---|

Self-portrait, 1577

|

|

| Born | 1547 Exeter, England

|

| Died | 7 January 1619 (aged 71–72) London, England

|

| Known for | Portrait miniatures |

| Patron(s) | Elizabeth I, James I |

Nicholas Hilliard (around 1547 – 7 January 1619) was a famous English artist. He was a goldsmith, meaning he worked with gold, and a limner, which was a painter who specialized in very small, detailed portraits called portrait miniatures. He is best known for painting members of the royal courts of Elizabeth I and James I of England.

Hilliard mostly created tiny oval miniatures, but he also painted some larger ones, up to about 25 centimeters tall. He even painted at least two well-known, half-length portraits of Queen Elizabeth I on wooden panels. He was a successful artist for 45 years, even though he often had money problems. His paintings still show us what Elizabethan England looked like, which was quite different from the rest of Europe at that time. His art style was traditional, but his paintings are beautifully made and have a special charm. This has kept his reputation strong as "the most important artist of the Elizabethan age."

Contents

Who Was Nicholas Hilliard?

Hilliard's Early Life and Family

Nicholas Hilliard was born in Exeter, England, in 1547. His father, Richard Hilliard, was also a goldsmith and a strong Protestant. Richard became the Sheriff of Exeter in 1568. Nicholas had three brothers; two also became goldsmiths, and one became a clergyman.

When he was young, Hilliard may have lived with John Bodley, a leading Protestant from Exeter. When the Catholic Queen Mary I of England came to power, John Bodley went into exile. In 1557, when Hilliard was ten, he was with the Bodley family in Geneva, Switzerland, attending a Calvinist church service led by John Knox. Hilliard didn't become a Calvinist, but he learned to speak fluent French, which was helpful later.

Hilliard painted a self-portrait when he was 13 years old in 1560. It is also said that he painted a portrait of Mary, Queen of Scots, when he was 18.

Becoming an Artist: Hilliard's Training

Hilliard became an apprentice to Robert Brandon (who died in 1591), the Queen's jeweler and a goldsmith in London. Some experts believe that Hilliard might have also learned the art of limning (miniature painting) from Levina Teerlinc during this time. She was the daughter of Simon Bening, a famous master of illuminated manuscripts from Flanders. Teerlinc became the court painter for Henry VIII after Holbein died.

After seven years of training, Hilliard became a freeman of the Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths in 1569. He then opened a workshop with his younger brother, John. In 1576, he married Alice Brandon (1556–1611), Robert Brandon's daughter. They had seven children together.

Hilliard's Career as a Royal Artist

Working for the Queen: Royal Limner

Hilliard finished his apprenticeship just when a new royal portrait painter was greatly needed. Two large portraits, the "Phoenix" and "Pelican" portraits, are thought to be by him and date from around 1572–1576. Hilliard was made the official limner (miniaturist) and goldsmith to Queen Elizabeth I. His first known miniature of the Queen is from 1572. By 1573, the Queen rewarded him for his "good, true and loyal service."

In 1571, Hilliard made a "book of portraitures" for the Earl of Leicester, who was the Queen's favorite. This likely helped him become known at court. Several of Hilliard's children were named after people in Leicester's group.

Time in France

Despite his royal support, Hilliard went to France in 1576. He wanted to "increase his knowledge" and hoped to earn money from French lords and ladies to help him when he returned to England. The English Ambassador in Paris, Sir Amyas Paulet, reported this and Hilliard stayed with him for much of the time. Francis Bacon was also part of the embassy, and Hilliard painted a miniature of him in Paris.

Hilliard stayed in France until 1578–1579. He spent time with other artists at the French court, including Germain Pilon, the Queen's sculptor, and George of Ghent, her painter. He also met the poet Ronsard.

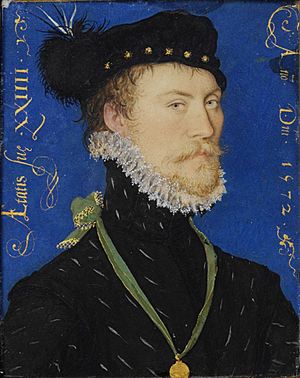

In 1577, Hilliard is mentioned in the papers of the duc d'Alençon, who was a suitor of Queen Elizabeth. He is listed as "Nicholas Belliart, peintre anglois" (English painter) and received a payment of 200 livres. A miniature of Madame de Sourdis, painted by Hilliard, is dated 1577. Other portraits believed to be his work include those of Gabrielle d'Estrées and la princesse de Condé.

Financial Challenges and Royal Support

Money was often a problem for Hilliard. A typical miniature cost about £3, which was a good price compared to other artists at the time. For example, a portrait of the Earl of Northumberland cost £3 in 1586. Around 1574, Hilliard lost money by investing in a gold mine in Scotland.

In 1599, Queen Elizabeth gave Hilliard an annual payment of £40. In 1617, he managed to get a special right from King James I to be the only one allowed to create miniatures and engravings of the King. Elizabeth had refused him this in 1584. Even with this, Hilliard was briefly put in Ludgate Prison that year because he couldn't pay a debt for someone else. His father-in-law didn't trust Hilliard with money, so his will in 1591 arranged for his daughter's allowance to be managed by the Goldsmiths' Company. In the same year, the Queen gave him £400, a large sum, after he made a new Great Seal.

In 1601, when his finances were low, Hilliard wrote to Robert Cecil, the Secretary of State. He asked for permission to leave London and live more cheaply in the countryside. He explained that his apprentices were now competing with him. Hilliard also asked Cecil to hire his son as a clerk because he couldn't support him in his own trade.

Recent studies of two paintings at Waddesdon Manor have changed what we know about Hilliard's work. Two large paintings, portraits of Sir Amyas Paulet and Queen Elizabeth, are now believed to be by him. These paintings are on French oak panels, not the Baltic oak usually used in England, suggesting they were painted during Hilliard's time in France.

Later Years and Artistic Legacy

After returning from France, Hilliard lived and worked in a house in Gutter Lane, near Cheapside, from 1579 to 1613. His son and student, Laurence, then took over the business for many years. Hilliard moved to a new home in St Martins-in-the-Fields, outside the city and closer to the Court. This new shop helped miniatures become popular beyond the royal court, reaching gentry and wealthy city merchants.

Besides Laurence, Hilliard's students included Isaac Oliver, who became very important, and Rowland Lockey. He also seemed to teach art to people who painted for fun. A letter from a young lady in London in 1595 mentions: "For my drawing, I take an hour in the afternoon... My Lady... tells me, when she is well, that she will see if Hilliard will come and teach me."

Hilliard continued to work as a goldsmith. He created beautiful "picture boxes" or jeweled lockets for miniatures, which were worn around the neck. An example is the Lyte Jewel in the British Museum, which King James I gave to a courtier in 1610. The Armada Jewel, given by Elizabeth to Sir Thomas Heneage, and the Drake Pendant, given to Sir Francis Drake, are other famous examples. Courtiers were expected to wear the Queen's likeness, especially at court, as part of the respect shown to the Virgin Queen. Elizabeth herself had a collection of miniatures, kept in a cabinet in her bedroom.

Hilliard's role as a miniaturist also included painting illuminated manuscripts. He was asked to decorate important documents, such as the founding charter of Emmanuel College, Cambridge (1584). This document shows Queen Elizabeth on her throne within a detailed frame of Flemish-style Renaissance decoration. He also seemed to design woodcut frames for book title pages, some of which have his initials. As a New Year's gift in 1584, Hilliard gave Queen Elizabeth a painting of the story of the five wise and foolish virgins.

King James I also highly favored Hilliard, just like Elizabeth did. In 1617, the King gave him a special patent, allowing him the sole right to create engraved royal portraits for twelve years. Hilliard had already been making these, though he likely used other engravers like Renold Elstrack to do the actual engraving. King James's generous gifts of portraits affected the quality of work from Hilliard's workshop. When the Earl of Rutland returned from Denmark, sixteen members of his group received gold chains with the king's picture.

The poet John Donne praised Hilliard's work in his poem The Storm (1597), showing how much his contemporaries respected him. Nicholas Hilliard died on 7 January 1619 and was buried in the church of St Martins-in-the-Fields, Westminster. In his will, he left money to the poor of the parish, to his two sisters, and some goods to his maidservant. The rest of his belongings went to his son, Lawrence Hilliard.

The largest collection of Hilliard's work is at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. The National Portrait Gallery and British Museum in London also have several pieces. Because miniatures were kept carefully, many are still in excellent condition.

Hilliard's Artistic Style

Hilliard wrote an important book about miniature painting, now called The Art of Limning (around 1600). This book is kept in the Bodleian Library. While it was once thought that another artist, John de Critz, wrote it, most experts now agree that Hilliard wrote The Art of Limning himself, possibly as instructions for one of his students, like Isaac Oliver.

In The Art of Limning, Hilliard mentions Hans Holbein the Younger, who was Henry VIII's court painter, and Albrecht Dürer. Hilliard likely knew Dürer's work only from his prints. Both Holbein and Dürer had died before Hilliard was born. In many ways, Hilliard's style was even more traditional than Holbein's. He also learned from French art, including their chalk drawings, and mentioned the artist and writer Gian Paolo Lomazzo. English art at the time was not as advanced as art in other parts of Europe. Hilliard's art was very different from the early-Baroque Italian artists of his time or his contemporary El Greco (1541–1614).

In The Art of Limning, Hilliard advised against using much chiaroscuro (strong contrasts between light and dark) in his paintings. This reflected Queen Elizabeth's views: "to show oneself best needs no shadow... Her Majesty chose her place to sit... in the open alley of a goodly garden, where no tree was near, nor any shadow at all..."

He stressed the importance of capturing "the grace in countenance, in which the affections appear." He believed a "wise drawer" (artist) should "watch" and "catch these lovely graces, witty smilings, and these stolen glances which suddenly like lightning pass." His usual method was to paint the entire face while the person was sitting for him, usually in at least two sessions. He kept several prepared flesh-colored blanks ready in different shades to save time. He would then faintly draw the outlines of the features with a very fine pointed squirrel-hair brush, before filling them in with light lines. He added new techniques, especially for clothes and jewels, often using tiny shadows from thick dots of paint to make pearls and lace look three-dimensional. A few unfinished miniatures show how he worked. He probably made few drawings, as not many have survived.

Hilliard's style didn't change much after the 1570s, except for some technical improvements. However, many of his later paintings of King James I and his family are not as strong as his earlier works. King James did not like sitting for his portrait, so Hilliard probably had few chances to paint him directly. From the 1590s onwards, his former student Isaac Oliver became a competitor. Oliver was appointed Limner to the new Queen Anne of Denmark in 1604, and then to Henry, Prince of Wales in 1610. Oliver had traveled abroad and developed a more modern style than his teacher. He was better at drawing with perspective, but he couldn't match Hilliard's freshness and ability to show a person's inner feelings.

Images for kids

Panel Portraits

Portrait Miniatures

-

Marguerite de Navarre, 1577

-

Sir Francis Drake, 1581

-

Sir Walter Raleigh, 1585

-

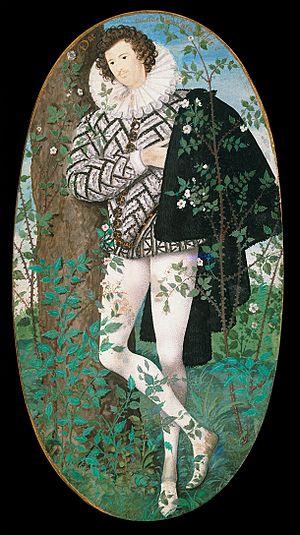

Unknown youth, 1585, Victoria and Albert Museum

-

James I, 1603–9, Victoria and Albert Museum

-

Christopher Hatton around 1589

-

Mary Sidney, Countess of Pembroke around 1590

-

Lettice Knollys, Countess of Leicester around 1590–1595

-

Elizabeth, Queen of Bohemia, daughter of James I, 1605–10

Elizabeth I

-

Miniature of Elizabeth I, around 1586–87, Nationalmuseum, Stockholm.

-

Miniature of Elizabeth I, 1572, National Portrait Gallery, London. Hilliard's earliest miniature of Elizabeth, painted when she was 38 years old.

-

Elizabeth I playing the lute around 1580

Drawings and Illuminations

-

Probably one of the alternative designs Elizabeth asked for her new Great Seal of England in 1584 – another version was chosen. Victoria and Albert Museum.

-

Drawing of Elizabeth Stuart, Electress Palatine, and her son Frederick Henry, likely for an engraving

See also

In Spanish: Nicholas Hilliard para niños

In Spanish: Nicholas Hilliard para niños

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |