Prayer Book Rebellion facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Prayer Book Rebellion |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of European wars of religion and the English Reformation |

|||||||

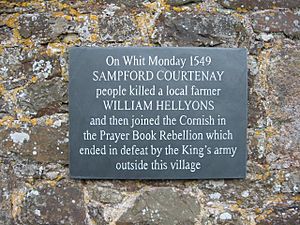

Memorial plaque in Sampford Courtenay |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Southwestern Catholics | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

John Winslade John Bury Robert Welch, Vicar of St Thomas, Exeter |

|||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| ~7,000 rebels | ~8,600 troops | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| At least 2,000 killed Unknown wounded |

At least 300 killed Unknown wounded |

||||||

| ~5,500 deaths | |||||||

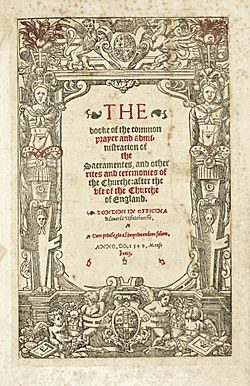

The Prayer Book Rebellion, also called the Western Rising, was a big uprising in Cornwall and Devon in 1549. It happened when a new prayer book, called the first Book of Common Prayer, was introduced. This book brought in new ideas from the English Reformation, which was a time of big changes in the Church in England.

Many people, especially in areas like Cornwall and Devon, were still very loyal to the old Catholic ways. They did not like the new prayer book. Also, times were tough with money problems, and the government made people use the English language in church, which upset those who spoke Cornish. All these things led to a burst of anger and the start of the rebellion. King Edward VI's government sent an army led by John Russell to stop the revolt. The rebels were defeated, and their leaders faced severe consequences a couple of months after the fighting began.

Contents

Why the Rebellion Started

One main reason for the Prayer Book Rebellion was the big religious changes happening in England. The new king, Edward VI, was very young. So, his main advisor, Lord Protector Somerset, made many new laws. These laws were part of the English Reformation. They aimed to change how people worshipped and what they believed. This was especially true in places like Cornwall and Devon, where people had strong Catholic beliefs.

Traditional religious events, like special parades and journeys to holy places, were stopped. Government officials were sent to remove all symbols of the Catholic faith. This was part of Thomas Cranmer's plan to make England more Protestant. In Cornwall, a man named William Body was given this job. People thought he was disrespecting their holy places. He was killed in April 1548.

Besides religious changes, there were also money problems. A new tax on sheep made things harder for farmers in the West Country. This region had a lot of sheep farms. Rumors spread that the tax would soon include other animals, which made people even more unhappy.

The local leaders were not strong enough to handle the growing anger. The main landowner in the area was not around much. This meant there was no one powerful nearby to calm things down.

Some people think the rebellion also had roots in Cornwall's desire to be independent from England. They did not like new laws from a faraway government. Earlier, in 1497, there was another Cornish rebellion. Also, King Henry VIII had closed down many monasteries between 1536 and 1545. These monasteries had supported Cornish and Devonian culture and learning. Their closure made people upset and ready to oppose future changes. Some historians believe that the Catholic Church had been good at supporting Cornish language and culture. So, attacks on their traditional religion made the people of Cornwall want to fight back.

After William Body's death, many Cornishmen were punished. Some were put to death at Launceston Castle. One priest, Martin Geoffrey, was taken to London and also put to death.

The Uprising Begins in Sampford Courtenay

The new prayer book was not accepted everywhere. In 1549, a new law, the Act of Uniformity, made it illegal to use the old Latin church services. This law started on a special day called Whitsunday. Local officials were told to make sure everyone followed the new rule.

The very next day, in a village called Sampford Courtenay in Devon, people forced their priest to go back to the old service. The rebels said the new English service was "like a Christmas game." This might have been because the new book had men and women walk to different sides of the church to receive a special blessing, which reminded them of country dancing. When officials came to enforce the new rules, a fight broke out, and one supporter of the new changes was killed.

After this, a group from Sampford Courtenay decided to march to Exeter to protest the new prayer book. As they moved through Devon, many more Catholic supporters joined them. Soon, they became a large force. They marched east to Crediton and then laid siege to Exeter. They demanded that all English church services be stopped. Even though some people inside Exeter supported the rebels, the city gates stayed closed for over a month.

Rebel Goals and Demands

In Cornwall and Devon, the new prayer book was the final straw for the people. For twenty years, they had faced difficulties, and prices for food like wheat had gone up four times. Also, common lands were being fenced off, and the attack on the Church, which was central to their lives, made people furious.

In Cornwall, an army gathered in Bodmin. Their leaders were Henry Bray, the mayor, and two Catholic landowners, Sir Humphrey Arundell and John Winslade. Many wealthy people sought safety in old castles. Some hid in St Michael's Mount, but the rebels surrounded them. The rebels created a lot of smoke by burning hay. With little food and worried women, the people inside had to give up. Another wealthy man, Sir Richard Grenville, hid in Trematon Castle. He was tricked into coming out to talk, then captured, and the castle was searched. Sir Richard and his friends were put in jail. The Cornish army then marched into Devon to join the Devon rebels near Crediton.

The rebels' main goal was religious. They wanted to bring back the old ways. Their slogan was "Kill all the gentlemen and we will have the Six Articles up again, and ceremonies as they were in King Henry's time." This also showed that they were upset with the wealthy landowners. They even demanded that rich families should have fewer servants. This might have been a way to challenge the power of the wealthy. Important people at the time, like Thomas Cranmer, believed the rebels were trying to start a class war. Lord Protector Somerset also thought that all the rebellions in 1549 showed a strong dislike for the wealthy.

The Cornish rebels were also worried about the English language in the new prayer book. At this time, the Cornish language was slowly being used less. However, in West Cornwall, many people still spoke Cornish. They were very angry that the church service was now in English. They wrote their demands, saying, "...and so we the Cornyshe men (whereof certen of us understande no Englysh) utterly refuse thys newe Englysh." Archbishop Cranmer, however, asked why they were upset about English when they had used Latin before and not understood that either.

Key Battles and Confrontations

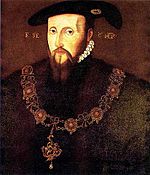

When news of the rebellion reached London, King Edward VI and his advisors were very worried. The Lord Protector, the Duke of Somerset, ordered Sir Gawen Carew to try and calm the rebels. At the same time, Lord John Russell was told to bring an army to stop the rebellion by force.

The rebels came from many different backgrounds. There were farmers, tin miners, and fishermen. Cornwall seemed to have a larger group of trained fighters than other areas of its size.

Crediton and Exeter

After the rebels passed Plymouth, two knights, Sir Gawen and Sir Peter Carew, tried to talk with the Devon rebels at Crediton. But their path was blocked, and they were attacked. Soon after, the Cornish rebels arrived. Their leader, Arundell, split his forces. One group went to Clyst St Mary to help villagers, and the main army advanced on Exeter. They surrounded the city for five weeks. The rebel leaders tried to convince John Blackaller, Exeter's mayor, to surrender, but he refused. The city gates stayed closed.

Battles Near Exeter

Lord John Russell, 1st Earl of Bedford's army arrived in Honiton. It included soldiers from Italy and Germany. With more troops coming, Russell would have over 8,600 well-armed and trained men. He thought the rebels had about 7,000 men. On July 28, Arundell tried to block Russell's army at Fenny Bridges. This battle was not clearly won by either side. About 300 men on each side died. Lord Russell and his army went back to Honiton.

On August 2, Russell's reinforcements arrived. His army of 5,000 men marched towards Exeter. They set up camp on Woodbury Common. On August 4, the rebels attacked, but the battle was not decisive. Lord Russell's army captured many prisoners.

Arundell's forces gathered again with 6,000 soldiers at Clyst St Mary. But on August 5, Russell's troops attacked them. After a fierce fight, Russell's army won. A thousand Cornish and Devonian rebels were killed, and many more were captured.

Clyst Heath Massacre

Russell set up camp on Clyst Heath. Here, he had 900 rebel prisoners killed. When Arundell's forces heard about this terrible event, they attacked again on August 6. Lord Grey, a commander, said he had never seen such a deadly fight. About 2,000 soldiers died in this battle.

Exeter is Saved

Lord Russell continued his attack and finally lifted the siege of Exeter. In London, a rule was made that the lands of those involved in the rebellion could be taken away. Arundell's land was given to Sir Gawen Carew, and Sir Peter Carew received John Winslade's land.

Final Battle at Sampford Courtenay

Lord Russell thought the rebels were defeated. But then he heard that Arundell's army was gathering again at Sampford Courtenay. This changed his plans. Russell's army grew even stronger with new troops. His army now had over 8,000 men, much more than the remaining rebels. Lord Grey and Sir William Herbert led the attack. A historian at the time wrote that the Cornish rebels fought until most of them were killed or captured. Lord John Russell reported that his army killed between 500 and 600 rebels in the battle. He said another 700 were killed as his army chased the retreating Cornish.

Aftermath and Consequences

Many rebels escaped, including Arundell, who fled to Launceston. There, he was captured and taken to London, along with Winslade, who was caught in Bodmin. In total, over 5,500 people lost their lives during the rebellion and the punishments that followed.

The King's advisors, the Duke of Somerset and Archbishop Thomas Cranmer, ordered that the attacks continue. Sir Anthony Kingston led the English and hired soldiers into Devon and Cornwall. They killed many people before the violence finally stopped. Ideas to translate the Prayer Book into Cornish were also rejected.

The many deaths in the Prayer Book Rebellion and the punishments that followed, along with the introduction of the English Prayer Book, were a big turning point for the Cornish language. Unlike Welsh, the Cornish language never had a full bible translation. Some studies suggest that before the rebellion, the Cornish language was actually getting stronger. Also, anti-English feelings were growing, which gave more reasons for the rebellion to happen.

See also

- Cornish Rebellion of 1497

- Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire Rising of 1549, which happened at the same time and for similar reasons

- Pilgrimage of Grace

- Rising of the North

- Religion in the United Kingdom

- Jenny Geddes, who sparked a later rebellion in Scotland

- List of topics related to Cornwall

- History of Devon