Battle of Sampford Courtenay facts for kids

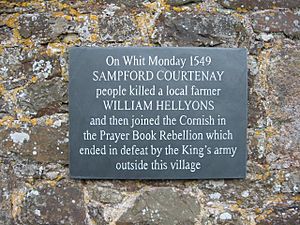

The Battle of Sampford Courtenay was a very important fight during the Western Rebellion of 1549. This rebellion happened because people in Cornwall and Devon were unhappy with changes to their church services.

Getting Ready for Battle

By August 1549, Humphrey Arundell was leading the rebel army. He gathered his troops at Sampford Courtenay in Devon. He was expecting 1,000 more soldiers from Winchester to join him. This place would be the site of the fifth and final battle of the Prayer Book Rebellion.

What Arundell didn't know was that someone in his own camp was secretly working against him. His secretary, John Kessell, had been telling John Russell, 1st Earl of Bedford, all about Arundell's plans. Russell was the head of the Council of the West, a powerful government group.

Lord Russell thought the rebels from Devon and Cornwall were already beaten. The news from Kessell changed his plans. Russell had also received more soldiers led by Sir Anthony Kingston. Now, Russell had an army of over 8,000 men. This was much larger than the rebel forces.

Russell moved his army on August 16. They camped overnight at Crediton. The next morning, scouts from both sides met by accident. This led to a small fight, and a Cornish captain named Maunder was captured.

The 1,000 men from Winchester never arrived to help Arundell. The main rebel army had dug in on high ground outside Sampford Courtenay. A smaller group led by Humphrey Arundell waited in the village. They knew this would be their last stand. The rebels were on their own against Russell's much larger army.

The Battle and What Happened Next

Lord Russell decided to attack from three different directions. Strong groups of soldiers led by Lord Grey and Sir William Herbert attacked the rebel camp first. Russell himself followed behind them. The fight was harder than Russell expected. The rebel camp had more defenders than he thought.

A fierce gun battle lasted for about an hour. This gave time for Russell's other two groups of soldiers to move in. One group was made up of Italian soldiers called arquebusiers. These were soldiers who used early firearms. The other group was German soldiers called Landsknechte. They were professional soldiers.

With almost all the government forces attacking them, the rebels had to retreat into the village. There, they faced heavy cannon fire. If the Cornish and West Devon rebels had soldiers on horseback, they might have won the battle.

John Hooker, a historian from Exeter at the time, wrote about the battle. He said the rebel army would not give up until most of them were killed or captured. Lord John Russell said his army killed between 500 and 600 enemy soldiers. He also said that chasing the rebels killed another 700.

The men from Devon tried to escape to Somerset. But one by one, they were caught. Many faced severe punishment from troops led by Sir Peter Carew and Sir Hugh Paulet. The Cornishmen headed home. They tried one last time to fight Russell at Okehampton. Russell planned another attack. But in the morning, he heard from Kessell, the informer. Kessell said the Cornish forces were mostly gone. The remaining Cornishmen had crossed back over the River Tamar into Cornwall.