Cornish Rebellion of 1497 facts for kids

The Cornish Rebellion of 1497 was a big protest by people in Cornwall, a region in the southwest of Britain. It happened because King Henry VII wanted to collect new taxes to pay for a war against Scotland. The people of Cornwall, especially the tin miners, were upset. They felt these taxes broke old promises made by King Edward I of England. These promises had said Cornwall would not have to pay certain taxes.

Contents

The Rebellion Begins

When King Henry VII asked for these new taxes, two men convinced many Cornish people to protest. These leaders were Michael Joseph, known as An Gof (which means "the Smith" in Cornish), a blacksmith from St Keverne, and Thomas Flamank, a lawyer from Bodmin.

About 15,000 people joined their army. They marched into Devon, gaining more supporters and supplies along the way. Their march was mostly peaceful, except for one small event in Taunton. From Taunton, they went to Wells, where a skilled soldier named Baron Audley joined them.

Marching Towards London

After sharing their complaints, the army left Wells. They marched through Bristol and Salisbury to Winchester, surprisingly without anyone stopping them. At this point, they had come a long way. Flamank suggested they go to Kent, a place known for past protests like the Peasants' Revolt of 1381. They hoped to get more support there.

However, they didn't find much help in Kent. Some of the army went home, while the rest turned towards Surrey.

Reaching Guildford and Blackheath

By June 13, 1497, the Cornish army reached Guildford in Surrey. King Henry VII was surprised by how big the rebellion was. He quickly called back his army of 8,000 men, which had been preparing to fight in Scotland. On the same day, Lord Daubeney, leading the King's army, set up camp at Hounslow Heath.

The King decided to attack the Cornish forces. Lord Daubeney sent 500 mounted spearmen to fight them. They clashed with the Cornish outside Guildford on June 14, 1497.

The Cornish army then left Guildford. They marched through Banstead and Chussex Plain to Blackheath. This was their final camp, overlooking the River Thames and the City of London. An Gof managed to keep his army together, even though they faced huge odds. Some Cornish soldiers left, but about 9,000 to 10,000 brave Cornish fighters remained.

The Battle of Deptford Bridge

The Battle of Deptford Bridge, also called the Battle of Blackheath, happened on June 17, 1497. It took place in what is now Deptford, south-east London, near the River Ravensbourne. This battle was the main event of the Cornish Rebellion.

King Henry VII had a much larger army of about 25,000 men. The Cornish army did not have the cavalry (soldiers on horseback) or artillery (cannons) that professional armies used back then. Henry cleverly spread rumors that he would attack on Monday. Instead, he attacked the Cornish at dawn on Saturday, June 17, 1497.

The King's forces were split into three groups. Two groups, led by Lords Oxford, Essex, and Suffolk, were to go around the Cornish army's right side and behind them. The third group waited in reserve. Once the Cornish were surrounded, Lord Daubeney and the third group were ordered to attack from the front.

Fighting at the Bridge

At the bridge over Deptford Strand, the Cornish had placed archers to stop the King's army from crossing the river. Lord Daubeney's spearmen had a tough fight here. They eventually captured the crossing, but they lost some men.

The Cornish had made a mistake. They did not send enough support for their men at the bridge. Their main army stood far back on the heath, near the top of the hill. Lord Daubeney and his troops poured across the bridge and bravely attacked the enemy. Daubeney himself got too far ahead and was captured by the Cornish. Amazingly, the Cornish simply let him go, and he quickly returned to the fight.

The Battle Continues

The other two Royal army groups attacked the Cornish exactly as planned. Since the Cornish were not well-armed or well-led, and had no horses or cannons, they were easily defeated. Estimates of the Cornish dead range from 200 to 2,000. Many of the defeated army were being killed when An Gof ordered them to surrender. He tried to escape but was captured in Greenwich. Lord Audley and Thomas Flamank were captured on the battlefield.

What Happened Next

By 2:00 PM, King Henry VII returned to the City in victory. He honored deserving people along the way and attended a special church service at St Paul's.

After the rebellion, the King made the people of Cornwall pay very high fines. This made many families poor for years. Some prisoners were sold into slavery, and their lands were taken and given to people loyal to the King. The rebels who managed to escape went home, and the rebellion ended.

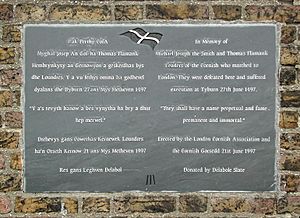

An Gof and Flamank were both executed in London on June 27, 1497. An Gof is said to have wished for "a name perpetual and a fame permanent and immortal" before he died. Thomas Flamank was quoted as saying, "Speak the truth and only then can you be free of your chains." Lord Audley, because he was a nobleman, was beheaded on June 28 at Tower Hill, London.

Remembering the Rebellion

In 1997, 500 years after the rebellion, a statue of the Cornish leaders, Michael An Gof and Thomas Flamank, was put up in An Gof's home village of St Keverne. A special plaque was also placed on Blackheath Common to remember them.

See also

In Spanish: Rebelión de Cornualles de 1497 para niños

In Spanish: Rebelión de Cornualles de 1497 para niños

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |