Thomas Cranmer facts for kids

Quick facts for kids The Right Reverend and Right Honourable Thomas Cranmer |

|

|---|---|

| Archbishop of Canterbury | |

Portrait by Gerlach Flicke, 1545

|

|

| Church | Church of England |

| Diocese | Canterbury |

| Enthroned | 3 December 1533 |

| Reign ended | 4 December 1555 |

| Predecessor | William Warham |

| Successor | Reginald Pole |

| Orders | |

| Consecration | 30 March 1533 by John Longland |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 2 July 1489 Aslockton, Nottinghamshire, England |

| Died | 21 March 1556 (aged 66) Oxford, England |

| Denomination | Protestantism (Anglicanism) |

| Profession | Priest |

| Alma mater | Jesus College, Cambridge |

| Sainthood | |

| Venerated in | Anglican Communion |

Thomas Cranmer (born 2 July 1489 – died 21 March 1556) was an important leader during the English Reformation. He served as the Archbishop of Canterbury for many years, working with King Henry VIII, King Edward VI, and for a short time, Queen Mary I.

Cranmer played a key role in helping King Henry VIII end his marriage to Catherine of Aragon. This event was a major reason why the English Church separated from the Pope in Rome. Cranmer also strongly supported the idea that the king, not the Pope, was the highest authority over the Church in England.

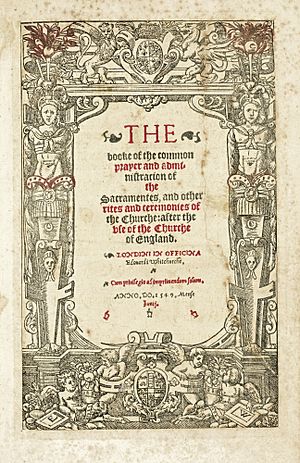

As Archbishop, Cranmer helped create the first rules and worship styles for the new Church of England. Under King Henry, he made some changes, like publishing the first official church service in English. But bigger changes happened when Edward VI became king. Cranmer wrote the first two versions of the Book of Common Prayer, which became the main worship book for the English Church. He also worked with other reformers to change ideas about the Eucharist (Communion), whether priests could marry, and the use of images in churches.

When the Catholic Queen Mary I came to power, Cranmer was put on trial for treason and heresy (beliefs against the official church). He was imprisoned for over two years. Under pressure, he signed several papers saying he would return to the Catholic Church. However, on the day he was to be executed, he bravely took back his statements. He died as a martyr for the English Reformation. His story is famously told in Foxe's Book of Martyrs. Today, his work lives on in the Church of England through the Book of Common Prayer and the Thirty-Nine Articles, which are important statements of Anglican faith.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Thomas Cranmer was born in 1489 in a village called Aslockton in Nottinghamshire, England. He was the younger son of Thomas Cranmer and Agnes Hatfield. His family was not super rich but was well-known.

When he was 14, after his father passed away, Thomas was sent to Jesus College, Cambridge. It took him eight years to earn his first degree, where he studied logic, old literature, and philosophy. He also started collecting old books from the Middle Ages. For his master's degree, he studied the works of important thinkers like Erasmus. He finished this degree in three years, in 1515, and became a Fellow at Jesus College.

Later, Cranmer married a woman named Joan. Even though he wasn't a priest yet, he had to leave his position at Jesus College because Fellows were not allowed to be married. To support himself and his wife, he worked as a teacher at Buckingham Hall. Sadly, Joan died during the birth of their first child. After this, Jesus College allowed Cranmer to return as a Fellow. He then began studying theology and became a priest around 1520. He earned his highest degree in theology in 1526.

Working for King Henry VIII

King Henry VIII's first marriage began in 1509 to Catherine of Aragon. After several miscarriages, they had a daughter, Mary, in 1516. By the 1520s, Henry still did not have a son to take over the throne. He believed this was a sign of God's disapproval and wanted to end his marriage.

In 1529, Cranmer was staying with relatives to avoid the plague in Cambridge. He met with two friends from Cambridge and they discussed the king's marriage problem. Cranmer suggested asking university experts across Europe for their opinions instead of just focusing on the legal case in Rome. King Henry liked this idea very much. Cranmer was then asked to join the royal team to gather these opinions.

In 1532, Cranmer became an ambassador to the court of the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V. While traveling, he visited the city of Nuremberg and saw the changes happening because of the Protestant Reformation. There, he met a reformer named Andreas Osiander. They became good friends, and Cranmer did something surprising: he married Margarete, Osiander's wife's niece. This showed that Cranmer was starting to agree with some Protestant ideas. However, he could not convince Emperor Charles, who was Catherine's nephew, to support the annulment of her marriage.

Becoming Archbishop of Canterbury

While Cranmer was in Italy, he received a letter saying he had been chosen as the new Archbishop of Canterbury. This happened after the previous archbishop, William Warham, died. Cranmer was told to return to England. This important job was arranged by the family of Anne Boleyn, whom Henry wanted to marry. Cranmer was not a very well-known church leader at the time, so his appointment surprised many people.

Henry paid for the special papers from the Pope needed for Cranmer to become Archbishop. These papers were easy to get because the Pope wanted to avoid a complete break with England. Cranmer became a bishop on 30 March 1533. Even before this, Cranmer continued to work on the king's marriage case, which became more urgent when Anne announced she was pregnant. Henry and Anne secretly married in January 1533. Cranmer found out about it two weeks later.

Over the next few months, Cranmer and the king worked out how the king's marriage would be judged by the church leaders. On 10 May, Cranmer opened a court session. Catherine of Aragon did not appear. On 23 May, Cranmer declared that Henry's marriage to Catherine was against God's law. He also said Henry would be excommunicated if he did not stay away from Catherine. Henry was now free to marry, and on 28 May, Cranmer confirmed Henry and Anne's marriage. On 1 June, Cranmer crowned Anne as queen.

The Pope was very angry about this, but he couldn't act too strongly because other rulers pressured him to avoid a full break with England. The Pope did say that Henry and his advisers (including Cranmer) would be excommunicated if Henry did not leave Anne. But Henry kept Anne as his wife. On 7 September, Anne gave birth to Elizabeth. Cranmer baptised her soon after and was one of her godparents.

By 1534, Cranmer had clearly broken away from Rome and was setting a new path for the Church. He supported the reform movement by replacing older church leaders with men who agreed with the new ideas. He also helped reformers in religious arguments, which upset those who wanted to stay connected to Rome.

Changes Under King Henry's Rule

Many bishops in England did not immediately accept Cranmer's authority. This led Thomas Cromwell, the king's chief minister, to take on a new role as the king's deputy for church affairs. Cromwell's role meant that he, not Cranmer, was the main person in charge of the king's church matters. Cranmer did not seem to mind being the junior partner, as he was a scholar and not as skilled in politics as Cromwell.

On 29 January 1536, Anne Boleyn lost her baby. The king then became interested in Jane Seymour. By April, he asked Cromwell to prepare for a divorce. Anne was sent to the Tower of London on 2 May. Cranmer was called to see her. He wrote a letter to the king expressing his doubts about Anne's guilt, but he accepted that her marriage would end. On 16 May, he saw Anne in the Tower and heard her confession. The next day, he declared her marriage null and void. Two days later, Anne was executed. Cranmer was one of the few who publicly showed sadness at her death.

The king and Cromwell worked to balance traditional and reform ideas in the church. This was seen in the Ten Articles, the first attempt to define what the Church of England believed. These articles recognized only three of the seven traditional sacraments: baptism, eucharist (Communion), and penance (confession). The other articles dealt with images, saints, ceremonies, and purgatory, showing a mix of old and new ideas. Cranmer and Cromwell, along with other church leaders, agreed to the Ten Articles in July 1536.

In late 1536, there were uprisings in northern England, known as the Pilgrimage of Grace. The protesters were very angry at Cromwell and Cranmer. After the rebellion was put down, the government tried to improve the Ten Articles. This led to The Institution of a Christian Man, also called the Bishops' Book, published in 1537. Cranmer helped lead the discussions for this book.

King Henry did not fully support the Bishops' Book at first. He was busy with Jane Seymour's pregnancy and the birth of his son, Edward. Jane died shortly after Edward's birth. Henry then began to work on the Bishops' Book himself. Cranmer's comments to the king showed his strong support for reformed ideas, like sola fide (salvation by faith alone). However, his words did not convince the king. A new statement of faith, the King's Book, was delayed until 1543.

In 1538, Henry and Cromwell tried to form an alliance with Lutheran princes in Germany. A group of German delegates came to England. Discussions about religious differences were held at Lambeth Palace, led by Cranmer. Progress was slow because Cromwell was busy and the English team had both conservative and reform-minded members. The talks failed, partly because a conservative bishop, Cuthbert Tunstall, influenced the king's decisions. Cranmer urged the Germans to continue, saying that "many thousands of souls in England" were at stake, but they left without an agreement.

Challenges and Continued Reforms

In 1539, King Henry started to favor conservative opinions in England. Parliament passed the Six Articles, which supported traditional Catholic beliefs like the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist and that priests should not marry. As this law was passed, Cranmer sent his wife and children out of England for their safety. The law forced other reformers, like Hugh Latimer, to resign from their church positions.

However, this setback for reformers did not last long. By September, Henry was unhappy with the results of the Six Articles. Cranmer and Cromwell were back in favor. The king asked Cranmer to write a new introduction for the Great Bible, an English translation of the Bible. Cromwell also arranged a marriage between Henry and Anne of Cleves, hoping to restart ties with the German Protestants. Henry did not like Anne when they met, but he married her anyway in a ceremony led by Cranmer. The marriage was quickly ended, and Cromwell was arrested and executed in July 1540.

Cranmer now found himself in a very important political position. The king trusted him completely. In 1541, while Henry was away, Cranmer was part of a council managing affairs for the king. During this time, he learned that Henry's new wife, Catherine Howard, had been unfaithful. An investigation proved this, and Catherine was executed in 1542.

King's Support and Final Years of Henry VIII

In 1543, some conservative churchmen tried to accuse Cranmer of wrongdoing. They presented their accusations to the king's council. Cranmer seemed unaware of this plot against him. For five months, Henry did nothing about the accusations. Finally, the king himself told Cranmer about the conspiracy. Henry appointed Cranmer as the chief investigator of the plot. Cranmer carried out raids, gathered evidence, and identified the leaders. He forgave many of the clergymen involved, but some were imprisoned, and one was executed. To show his trust, Henry gave Cranmer his personal ring. When the Privy Council tried to arrest Cranmer, the ring showed them that the king supported him.

With the king's support, Cranmer quietly continued his church reforms, especially in worship. In 1544, the first official church service in English, called the Exhortation and Litany, was published. It is still used today in the Book of Common Prayer. This service removed prayers to saints. More reformers were elected to Parliament, and new laws were introduced to lessen the impact of the Six Articles.

In 1546, conservatives made one last attempt to challenge the reformers. They targeted several reformers connected to Cranmer. However, powerful reform-minded nobles, Edward Seymour and John Dudley, returned to England and helped turn the situation around. Cranmer did not seem to be involved in these political struggles.

Cranmer performed his last duties for King Henry on 28 January 1547. Instead of giving Henry the traditional last rites, Cranmer gave a reformed statement of faith while holding the king's hand. Cranmer was very sad about Henry's death. It was said that he grew a beard to show his grief and his break with the old Church, as many Continental reformers did. On 31 January, he was among those who carried out the king's will, which named Edward Seymour as the Lord Protector for the young King Edward VI.

Reforms Under Edward VI

With Edward VI as king and Edward Seymour as Lord Protector, the reformers gained power. In 1547, churches were told to get a copy of the Homilies, a book of sermons. Four of these sermons were written by Cranmer. In his sermons, Cranmer emphasized that salvation comes through faith, not just through good actions or church ceremonies.

Cranmer's ideas about the Eucharist (Communion) continued to change, influenced by reformers from Europe. He had been in touch with Martin Bucer for years. After a war in Europe, England became a safe place for persecuted reformers. Cranmer invited important theologians like Peter Martyr and Bernardino Ochino to England. Their ideas, especially about the Eucharist, further influenced Cranmer.

In 1549, Cranmer invited Bucer and Paul Fagius to England, promising them places at English universities. Cranmer was very happy to finally meet Bucer. He needed these scholars to train new preachers and help reform church services and beliefs.

The Book of Common Prayer

As English became more common in church services, there was a clear need for a single, official worship book. Meetings to create what would become the 1549 Book of Common Prayer began in September 1548. The people involved included both traditionalists and reformers. In December, Cranmer publicly stated that he no longer believed in the physical presence of Christ in the Eucharist, but only a spiritual presence. Parliament then approved the Prayer Book and allowed priests to marry.

It is hard to know exactly how much of the Prayer Book Cranmer wrote himself. Scholars have found that he used many sources, including older English church services and writings from Lutheran reformers. However, Cranmer is given credit for editing and structuring the book.

The new Prayer Book became compulsory on 9 June 1549. This led to protests in some parts of England, known as the Prayer Book Rebellion. The rebels demanded the return of the Six Articles, Latin mass, and prayers for souls in purgatory. Cranmer wrote a strong response to these demands, criticizing the rebellion. He also gave a sermon defending the official Church.

Strengthening Reforms

The Prayer Book Rebellion caused problems for the government. A group of powerful council members, led by John Dudley, removed Edward Seymour from power in October 1549. Even though some conservative politicians supported this change, the reformers kept control of the government, and the English Reformation continued. Cranmer helped move his former chaplain, Nicholas Ridley, to a more important church position in London.

In 1550, Cranmer and Bucer worked together to create the Ordinal, which set out the services for ordaining deacons, priests, and bishops. Cranmer also wrote Defence of the True and Catholic Doctrine of the Sacrament of the Body and Blood of Christ, which explained the Eucharist beliefs in the Prayer Book. In this book, he compared traditional Catholic practices like pilgrimages to weeds, saying that the roots of these weeds were beliefs like transubstantiation (the idea that the bread and wine physically become Christ's body and blood).

Bucer was worried that the reforms were not happening fast enough, but Cranmer assured him that the 1549 Prayer Book was just the first step. Cranmer kept in close contact with Bucer. This helped during a disagreement about church clothes. A reformer named John Hooper objected to wearing traditional church vestments. Cranmer and Ridley stood firm, arguing that changes should happen carefully and under government authority. Hooper eventually gave in and was consecrated as bishop wearing the required vestments.

Final Reform Plans

Cranmer's political influence lessened when Edward Seymour was arrested again in October 1551 and later executed. This created a rift between Cranmer and John Dudley, who was now the main power in the government. Despite this, Cranmer worked on three major projects: revising church law, revising the Prayer Book, and creating a statement of church beliefs.

The old Catholic church laws needed to be updated after England broke from Rome. Cranmer formed a committee in December 1551 to work on this. He invited Peter Martyr, and even Hooper and Jan Łaski, showing his willingness to forgive past disagreements. Cranmer hoped to unite all the reformed churches of Europe under England's leadership to stand against the Catholic Church's Council of Trent. In March 1552, he invited important European reformers like John Calvin and Philipp Melanchthon to come to England for a church council. However, they were unable to come. Cranmer replied, "Meanwhile, we will reform the English Church to the utmost of our ability."

Cranmer also led the revision of the Prayer Book. This work began in late 1549. Peter Martyr and Bucer's ideas greatly influenced the changes. The new book made it clear that the presence of Christ in the Eucharist was spiritual, not physical. It also removed prayers for the dead, as these implied support for purgatory. The Act of Uniformity 1552 made the new book compulsory from 1 November.

The final version of the Prayer Book was published almost at the last minute because of Dudley's involvement. Dudley met a Scottish reformer named John Knox and brought him to London. Knox attacked the practice of kneeling during communion. The Privy Council temporarily stopped the printing of the new Prayer Book and asked Cranmer to revise it. Cranmer argued that Parliament, with the king's approval, should decide on changes to the church service. The council decided to keep the liturgy as it was but added a note, called the Black Rubric, explaining that kneeling at communion did not mean worshiping the bread and wine.

Cranmer also worked on a statement of beliefs that eventually became the Forty-Two Articles. By September 1552, Cranmer and his friend John Cheke were working on drafts. When the Forty-Two Articles were published in May 1553, the title page wrongly said they were agreed upon by the Convocation (assembly of clergy) and published by the king's authority. Cranmer complained about this, but the council avoided giving a direct answer. Cranmer was given the difficult task of asking bishops to agree to the articles, even though many opposed them.

Trials, Recantations, and Execution

King Edward VI became very ill in 1553. The council tried to persuade judges to name Lady Jane Grey, Edward's Protestant cousin, as the next queen instead of Mary, who was Catholic. On 17 June 1553, the king made his will, naming Jane as his successor, which went against a previous law. Cranmer tried to speak to Edward alone but was refused. Edward told him he supported his will. Cranmer decided to support Jane.

By mid-July, there were revolts in favor of Mary, and support for Jane quickly fell. Mary was proclaimed queen, and many of Jane's supporters were imprisoned. Cranmer was not immediately arrested. On 8 August, he led Edward's funeral using the Prayer Book services. During this time, he advised others, like Peter Martyr, to leave England, but he chose to stay. Protestant bishops were removed, and conservative clergy were restored to their positions.

Cranmer did not give up easily. When rumors spread that he had allowed the Catholic mass in Canterbury Cathedral, he declared them false. He stated that the beliefs and religion under King Edward VI were "more pure and according to God's word, than any that hath been used in England these thousand years." The government saw this as rebellion. On 14 September, he was ordered to appear before the council and was sent to the Tower of London with Hugh Latimer and Nicholas Ridley.

On 13 November 1553, Cranmer and four others were tried for treason, found guilty, and sentenced to death. Many witnesses said Cranmer had encouraged heresy. In February 1554, Lady Jane Grey and other rebels were executed. Then, attention turned to the Protestant church leaders. On 8 March 1554, Cranmer, Ridley, and Latimer were moved to Bocardo Prison in Oxford for a second trial for heresy. Cranmer managed to send a letter to Peter Martyr, who had fled to Strasbourg, saying, "I pray that God may grant that we may endure to the end!"

Cranmer stayed in Bocardo prison for 17 months before his trial began on 12 September 1555. The trial was under the Pope's authority. Cranmer admitted to the facts presented but denied any treachery or heresy. Latimer and Ridley were tried shortly after Cranmer and were burned at the stake on 16 October. Cranmer was forced to watch. On 4 December, Rome decided Cranmer's fate, removing him as archbishop and allowing the government to carry out his sentence.

In his final days, Cranmer's situation changed, leading to several recantations (statements taking back his beliefs). On 11 December, he was moved to a house where he was treated as a guest. He debated with a friar about the Pope's authority and purgatory. In his first four recantations, he submitted to the king and queen and recognized the Pope as head of the church. On 14 February 1556, he was stripped of his holy orders and sent back to prison. These statements were not enough for Edmund Bonner, a conservative bishop.

On 24 February, Cranmer's execution was set for 7 March. Two days later, he issued a fifth statement, which was a true recantation. He rejected all Protestant theology, fully accepted Catholic beliefs, including the Pope's authority and transubstantiation, and said there was no salvation outside the Catholic Church. He expressed joy at returning to the Catholic faith and received forgiveness. Cranmer's burning was postponed. Normally, this would have saved him, but Queen Mary wanted him executed. His last recantation was issued on 18 March, a confession of sin. Despite church law saying that those who recant should be spared, Mary was determined to make an example of Cranmer.

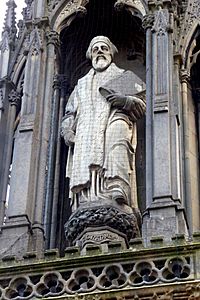

Cranmer was told he could make a final recantation in public at the University Church. He wrote his speech beforehand. On the day of his execution, 21 March 1556, he began with a prayer and urged obedience to the king and queen. But then, unexpectedly, he changed his speech. He took back all the recantations he had signed since his degradation, saying that his hand, which signed them, would be burned first. He then declared, "And as for the pope, I refuse him, as Christ's enemy, and Antichrist with all his false doctrine."

He was pulled from the pulpit and taken to the place where Latimer and Ridley had been burned. As the flames rose, he put his right hand into the fire, calling it "that unworthy hand." His dying words were, "Lord Jesus, receive my spirit...; I see the heavens open and Jesus standing at the right hand of God."

Legacy

The government of Queen Mary tried to hide what Cranmer really said at his execution, but the truth soon became known. This made it hard for Mary's message to be effective. Protestants also found it difficult to use his story at first because of his recantations. However, John Foxe later told Cranmer's story powerfully in his book Acts and Monuments in 1563.

Cranmer's family had gone to Europe in 1539. They returned to England after Edward VI became king in 1547. His daughter, Margaret, was likely born in the 1530s, and his son, Thomas, later. When Mary became queen, Cranmer's wife, Margarete, fled to Germany, and his son was taken to Europe by Cranmer's brother. Margarete later married Cranmer's publisher, Edward Whitchurch. They returned to England after Mary's reign. Cranmer's children died without having their own children, so his family line ended.

When Elizabeth I became queen in 1558, she restored the Church of England's independence from Rome. The church she re-established was very similar to the Edwardian Church of 1552. The Elizabethan Prayer Book was mostly Cranmer's 1552 edition, but without the "Black Rubric." In 1563, the Forty-Two Articles were changed to become the Thirty-Nine Articles, which are still important statements of Anglican faith today. Many reformers who had left England returned and continued their work in the Church.

Cranmer cared most about keeping the king as the head of the church and spreading reformed Christian ideas. He is best remembered for his contributions to the English language and to English culture. His writing style helped shape the English language, and the Book of Common Prayer is a major work of English literature that has influenced Anglican worship for hundreds of years.

Some historians see Cranmer as someone who changed his beliefs to fit the situation, or as a tool of the king. Others believe he sometimes went against his own principles. However, most agree that Cranmer was a dedicated scholar whose life showed both strengths and weaknesses as a very human reformer.

The Anglican Communion remembers Thomas Cranmer as a Reformation Martyr on 21 March, the anniversary of his death. He is also honored in the Church of England's calendar of saints with a special day. The U.S. Episcopal Church honors him with Hugh Latimer and Nicholas Ridley on 16 October.

See also

In Spanish: Thomas Cranmer para niños

In Spanish: Thomas Cranmer para niños

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |