Catherine Howard facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Catherine Howard |

|

|---|---|

A small portrait by Hans Holbein the Younger that might show Catherine Howard

|

|

| Queen consort of England | |

| Tenure | 28 July 1540 – 23 November 1541 |

| Born | c. 1524 Lambeth, London |

| Died | 13 February 1542 (aged 16–21) Tower of London, London |

| Burial | 13 February 1542 Church of St Peter ad Vincula, Tower of London, London |

| Spouse | |

| House | |

| Father | Lord Edmund Howard |

| Mother | Joyce Culpeper |

| Signature | |

Catherine Howard (born around 1524 – died 13 February 1542), sometimes spelled Katheryn Howard, was the Queen of England from 1540 to 1541. She became queen as the fifth wife of Henry VIII. Catherine was the daughter of Lord Edmund Howard and Joyce Culpeper. She was also a cousin to Anne Boleyn, who was Henry VIII's second wife. Her uncle, Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk, was an important person at Henry's court. He helped Catherine get a job in the home of Henry's fourth wife, Anne of Cleves. There, King Henry noticed Catherine. They married on 28 July 1540 at Oatlands Palace in Surrey. This was just 19 days after Henry's marriage to Anne of Cleves ended. Henry was 49 years old, and Catherine was between 15 and 21. Catherine lost her title as queen in November 1541 and died three months later.

Contents

Early life

Catherine was likely born in Lambeth, London, around 1524. We do not know her exact birth date. After her mother died around 1528, Catherine and some of her brothers and sisters went to live with her father's stepmother. This was Agnes Howard, the Dowager Duchess of Norfolk. The Dowager Duchess had large homes at Chesworth House in Horsham, Sussex, and at Norfolk House in Lambeth. Many servants and young relatives lived there. It was common for noble children to be raised in other noble homes back then. However, the care at Chesworth House and Lambeth was not very strict. The Dowager Duchess was often away at court. She did not seem to be very involved in raising the young people in her care.

In the Duchess's home, Catherine was influenced by some older girls. These girls were not always well-behaved. Catherine was not as well-educated as some of Henry's other wives. But she could read and write, which was impressive for her time. People often described her as lively, cheerful, and quick. She was not known for being serious or very religious. She loved her dance lessons but would often get distracted and make jokes. She also cared deeply for animals, especially dogs.

Around 1536, at the Duchess's home in Horsham, Catherine started music lessons. One of her teachers was Henry Mannox. They became very close. Mannox's exact age is not known, but he was likely in his early to mid-twenties. Catherine stopped seeing Mannox in 1538. Soon after, Francis Dereham, who worked for the Dowager Duchess, became close to Catherine. They even called each other "husband" and "wife." Many of Catherine's friends knew about their relationship. It seems to have ended in 1539. However, Catherine and Dereham might have planned to marry when he returned from Ireland.

Arrival at court

Catherine's uncle, the Duke of Norfolk, helped her get a job at court. She became a lady-in-waiting in the household of the King's fourth wife, Anne of Cleves. As a young and pretty lady-in-waiting, Catherine quickly caught Henry's attention. The King had not been very interested in Anne of Cleves from the start. Catherine's family, the Howards, may have hoped she would bring them more power at court.

As the King became more interested in Catherine, the Howard family gained more influence. Her youth, beauty, and lively spirit charmed the King, who was middle-aged. He said he had never met anyone like her. Within months of her arrival at court, Henry gave Catherine gifts of land and expensive clothes. Henry called her his "very jewel of womanhood." The French ambassador, Charles de Marillac, thought she was "delightful." A portrait by Holbein shows a young girl with reddish-brown hair and a nose typical of the Howard family. Catherine was said to have a "gentle, earnest face."

Marriage

(1509–1533)

(1533–1536)

(1536–1537)

(1540)

(1540–1542)

(1543–1547)

King Henry and Catherine married on 28 July 1540. The wedding took place at Oatlands Palace. Catherine was a teenager, and Henry was 49. Catherine chose a French motto: "Non autre volonté que la sienne", which means "No other will but his." The marriage was announced to the public on 8 August. Prayers were said for them at Hampton Court Palace. Henry "let her have everything she wanted" because of her cheerful nature.

Catherine was young, happy, and carefree. She was too young to handle important government matters. However, every night, Sir Thomas Heneage, a royal official, would visit her room. He would tell her about the King's health. There were no plans for a coronation, but she still traveled by royal boat into the City of London. There was a gun salute and people cheered for her. She was given Baynard's Castle as her home. Not much changed at court, except that many members of the Howard family arrived. Every day, she wore new clothes in the French style. These clothes were decorated with precious jewels and gold on the sleeves.

The Queen left London in August 1540 to avoid the plague. The royal couple traveled on their honeymoon through Reading and Buckingham. The King spent a lot of money to celebrate his marriage. He made many changes and improvements at the Palace of Whitehall. Then, he gave more expensive gifts for Christmas at Hampton Court Palace.

That winter, the King's bad moods grew worse. This was partly because of pain from his leg sores. He accused his advisors of lying. He also began to regret having Thomas Cromwell executed. After a dark and sad March, his mood improved at Easter.

Plans were made in case the Queen became pregnant. The French ambassador reported on 15 April that if she was pregnant, she would be crowned at Whitsuntide.

Downfall

Catherine may have had a close relationship with Henry's favorite male courtier, Thomas Culpeper, during her marriage to the King. Dereham later said that Culpeper "had taken [Henry's] place in the Queen's affections." Catherine had thought about marrying Culpeper when she was a lady-in-waiting to Anne of Cleves.

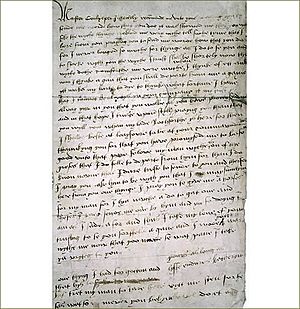

Culpeper called Catherine "my little, sweet fool" in a love letter. It is believed that in spring 1541, they met in secret. These meetings were supposedly arranged by Jane Boleyn, Viscountess Rochford (Lady Rochford). She was the widow of Catherine's cousin, George Boleyn, who was Anne Boleyn's brother.

During the investigation, a love letter written in the Queen's own handwriting was found in Culpeper's room. This is the only letter from her that still exists, apart from her later "confession."

On All Saints' Day, 1 November 1541, the King was praying in the Chapel Royal. There, he received a letter with accusations against Catherine. On 7 November 1541, Archbishop Cranmer and other advisors went to Winchester Palace to question her.

Imprisonment and death

If it was proven that Catherine had promised to marry Dereham before marrying the King, her marriage to Henry would have been invalid. This would have allowed Henry to end their marriage and send her away to live in poverty. However, Catherine strongly denied any such promise.

Catherine lost her title as queen on 23 November 1541. She was then held at the new Syon Abbey in Middlesex, which used to be a convent. She stayed there through the winter of 1541. A royal advisor made her return a ring that the King had given her. This ring had belonged to Anne of Cleves. Returning it was a sign that she had lost her royal rights. The King was at Hampton Court, but she never saw him again. Even with all these actions, her marriage to Henry was never officially ended.

Culpeper and Dereham were charged with high treason on 1 December 1541. They were executed on 10 December 1541. Many of Catherine's relatives were also held in the Tower. They were found guilty of hiding information about treason. They were sentenced to life in prison and lost all their belongings. Her uncle, the Duke of Norfolk, stayed away from the scandal. He wrote a letter of apology, blaming everything on his niece and stepmother. His son, Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, who was a poet, remained a favorite of the King.

Catherine remained in an uncertain state until Parliament passed a special law on 29 January 1542. This law made it treason, punishable by death, for a queen to not tell the king about her past relationships within 20 days of their marriage. This law made Catherine clearly guilty. No formal trial was held for her.

When the King's advisors came for her, she reportedly panicked and screamed. They took her to a boat that would carry her to the Tower on Friday, 10 February 1542. Her boat passed under London Bridge, where the heads of Culpeper and Dereham were displayed. Entering through the Traitors' Gate, she was led to her prison cell. The next day, the special law was approved. Her execution was set for 7:00 am on Monday, 13 February 1542. Sir John Gage, as the Constable of the Tower, oversaw the arrangements.

At her execution, Catherine spoke traditional last words. She asked for forgiveness for her sins. She said she deserved to die for betraying the king, who had always treated her kindly. She called her punishment "worthy and just." She asked for mercy for her family and prayers for her soul. These kinds of speeches were common for people executed back then. They were often meant to protect their families, as the condemned person's last words would be told to the King.

Lady Rochford was executed right after Catherine on Tower Green. They were buried in an unmarked grave in the nearby chapel of St. Peter ad Vincula. Catherine's cousins, Anne Boleyn and George Boleyn, were also buried there. Other cousins were in the crowd, including the Earl of Surrey. King Henry did not attend. Catherine's body was not found during chapel repairs in Queen Victoria's time. She is remembered on a plaque on the west wall dedicated to all who died in the Tower.

Portraits

Artists continued to include Jane Seymour in pictures of King Henry VIII even after she died. This was mainly because Henry still favored her as the only wife who gave him a son. Most artists copied the portrait by Hans Holbein the Younger because it was the only full-sized picture available. There is no proof that Catherine Howard ever had her portrait painted. Any picture of Catherine might have been destroyed after she died. Or they might have been ignored until later generations wondered who they were. There is no confirmed picture of Catherine Howard from her time. People still debate who is shown in possible portraits.

Small portraits

Two small portraits by Hans Holbein the Younger might be the only pictures of Catherine painted when she was alive. One is in the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle. The other is in the Buccleuch Collection. The historian David Starkey believes the Royal Collection version was painted when Catherine was queen. This is based on details of her clothing and the painting style. In this portrait, she wears a pendant jewel. This jewel is similar to one in Holbein's portrait of Jane Seymour and identical to one in the portrait of Henry VIII's third queen.

Her necklace of pearls and rubies set in gold looks very much like those seen in portraits of Henry VIII's other wives. This includes Jane Seymour and is identical to Catherine Parr's in the Hastings portrait. The necklace and pendant might have been given to Catherine by Henry VIII when they married in 1540. She is the only queen from that time whose appearance is not already known and who fits the dating. For female subjects, duplicate small portraits only exist for queens during this period. There are no other likely pictures of her to compare them to. Both versions have long been known as Catherine Howard, since 1736 for the Buccleuch version and at least the 1840s for the Windsor version.

Art historian Franny Moyle believes the Royal Collection small portrait is not Catherine Howard. Instead, she thinks it shows Henry VIII's fourth wife, Anne of Cleves. The small portrait has been linked to Catherine because it is from 1540, the year she married the king. Also, the person in the portrait wears jewels that were in Catherine's collection. Moyle noticed that the person in the portrait looked very much like Holbein's 1539 small portrait of Anne. She also found that Holbein, known for his hidden meanings, put the small portrait on a playing card showing the four of diamonds. She thought this might refer to Anne as Henry's fourth queen. Moyle also noted that jewels were often passed between queens. So, the jewels could have been Anne's too.

Other portraits

A drawing by Holbein (shown below) is also often said to be Catherine Howard. However, this does not seem to be true.

-

Unknown woman engraved as Catherine Howard, 1797, by Francesco Bartolozzi after Hans Holbein

A portrait of a lady in black, by Hans Holbein the Younger, was identified as Catherine Howard in 1909. This portrait (below), from around 1535–1540, is shown at the Toledo Museum of Art. It is called Portrait of a Lady, probably a Member of the Cromwell Family'. Two copies exist. A 16th-century copy at Hever Castle is shown as Portrait of a Lady, thought to be Catherine Howard'. The National Portrait Gallery shows a similar painting, Unknown woman, formerly known as Catherine Howard'. This one is from the late 17th century. The original portrait has "ETATIS SVÆ 21" written on it. This means the lady was 21 years old. This portrait has long been linked to Henry VIII's young queen. But now, she is thought to be a member of the Cromwell family.

In 1967, art historian Sir Roy Strong noted that both the Toledo portrait and the National Portrait Gallery version appear in a series of portraits of the family of Protector's uncle, Sir Oliver Cromwell. They have connections to the Cromwell family. He argued that the Toledo Museum of Art portrait "should show a lady of the Cromwell family aged 21 around 1535–40." He suggested the lady might be Elizabeth Seymour, wife of Gregory Cromwell, 1st Baron Cromwell. She was the son of Thomas Cromwell, Earl of Essex. He said that the clothing, especially the sleeves, matched Holbein's Christina of Denmark from 1538. Herbert Norris said the lady wears a sleeve style set by Anne of Cleves. This would mean the portrait was painted after 6 January 1540, when Anne married Henry VIII. The original Holbein is dated 1535–1540. But the National Portrait Gallery dates their copy to the late 1600s. This would mean the person was still important enough to be remembered over a century later, unlike Catherine.

Historians Antonia Fraser and Derek Wilson believe the portrait likely shows Elizabeth Seymour. Antonia Fraser argued that the person is Jane Seymour's sister, Elizabeth. She was the widow of Sir Anthony Ughtred. This is because the lady looks like Jane, especially around the nose and chin. She also wears black, which could mean she is in mourning. However, her rich black clothing, which showed wealth, did not always mean mourning. Her jewelry suggests otherwise. Derek Wilson noted that in August 1537, Cromwell arranged for his son, Gregory, to marry Elizabeth Seymour. She was the queen's younger sister. So, he was related to the king by marriage. This was an event worth remembering with a portrait of his daughter-in-law. The painting was owned by the Cromwell family for centuries.

-

Portrait of an Unknown Lady, around 1535, by Lucas Horenbout (1490/95–1544)

Recently, Susan James, Jamie Franco, and Conor Byrne have said that a Portrait of a Young Woman at the Metropolitan Museum of Art is a portrait of the queen. This painting is believed to be from the workshop of Hans Holbein. However, Brett Dolman has noted that this idea is "not supported by the evidence."

Images for kids

-

A small portrait by Hans Holbein the Younger that might show Catherine Howard

-

Unknown woman engraved as Catherine Howard, 1797, by Francesco Bartolozzi after Hans Holbein

-

Portrait of an Unknown Lady, around 1535, by Lucas Horenbout (1490/95–1544)

See also

In Spanish: Catalina Howard para niños

In Spanish: Catalina Howard para niños

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |