Jane Boleyn, Viscountess Rochford facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Jane Boleyn

|

|

|---|---|

| Viscountess Rochford | |

| Born | Jane Parker c. 1505 Norfolk, England |

| Died | 13 February 1542 (aged 36–37) Tower of London, England |

| Buried | Chapel Royal of St. Peter ad Vincula, Tower of London 51°30′31″N 0°04′37″W / 51.508611°N 0.076944°W |

| Noble family | Boleyn |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Father | Henry Parker, 10th Baron Morley |

| Mother | Alice St John |

Jane Boleyn, also known as Jane Parker, was an important English noblewoman who lived from about 1505 to 1542. She was married to George Boleyn, Viscount Rochford. George was the brother of Anne Boleyn, who became the second wife of King Henry VIII. Jane worked in the royal household for King Henry's first wife, Catherine of Aragon. Later, she also served as a lady-in-waiting (a helper to the Queen) for Henry's third, fourth, and fifth wives. She was executed in 1542 along with King Henry's fifth wife, Catherine Howard.

Contents

Early Life and Royal Connections

Jane Parker was born in Norfolk, England, around 1505. Her parents were Henry Parker, 10th Baron Morley, and Alice St John. Her family was very wealthy and well-known. They were respected members of the English nobility.

Jane's father was a smart man who loved culture and learning. Jane herself was sent to the royal court when she was a young teenager. She joined the household of King Henry VIII's first wife, Catherine of Aragon. In 1520, she traveled with the royal family to France for a big event called "The Field of the Cloth of Gold".

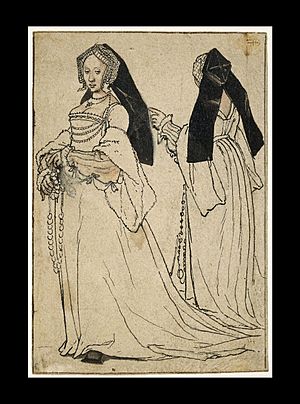

What Did Jane Look Like?

For a long time, people thought there were no pictures of Jane. However, her biographer, Julia Fox, suggests that a painting by Holbein might show Jane. She also thinks that Holbein's drawings of an "unknown woman in Tudor dress" might give us a good idea of what Jane looked like.

Jane was likely considered attractive. In 1522, she was chosen to perform in a special play at court called "Château Vert". The seven women chosen for this play were picked partly because they were beautiful. Among them were the King's sister, Mary Tudor, Queen of France, and Jane's future sisters-in-law, Anne Boleyn and Mary Boleyn.

Marriage to George Boleyn

Around 1524 or 1525, Jane married George Boleyn, Viscount Rochford. George was the brother of Anne Boleyn. At this time, Anne was not yet married to the King, but she was already a very important person at court.

As a wedding gift, King Henry gave Jane and George a home called Grimston Manor in Norfolk. In 1529, George became a viscount, which is a noble title. This meant Jane gained the title of Viscountess Rochford. People at court often called her "Lady Rochford."

As the Boleyn family became more powerful, Jane and George were given the Palace of Beaulieu in Essex as their main home. They decorated it beautifully with a fancy chapel, a tennis court, and even a bathroom with hot and cold running water! Their bed was covered in expensive fabrics.

It's not clear how well Jane got along with her sister-in-law, Anne Boleyn. Many people believe Jane was jealous of Anne.

Life as a Widow

George Boleyn was executed on 17 May 1536. His sister, Anne Boleyn, was executed two days later. It's not known if Jane saw either execution. After Anne's death, many people felt sorry for her. This led some to see Jane as a cruel person who helped cause Anne's downfall.

After her husband's death, Jane faced financial difficulties. The Boleyn family's wealth and titles usually passed down through the male family members. Since George had no sons, much of the family fortune was lost. Jane continued to use the title of Viscountess Rochford.

Returning to Court

Jane was away from court for several months after George's death. She worked hard to get her finances in order. The Boleyn family eventually gave her a yearly payment of £100. This was less than she used to have, but it was enough for her to live as a noblewoman. This was important because she wanted to return to court.

It's not known exactly when she returned, but she became a lady-in-waiting to King Henry's third wife, Queen Jane Seymour. As a viscountess, she could bring her own servants and live in the King's palaces.

After Queen Jane Seymour died, the King married Anne of Cleves. Jane Boleyn continued to serve as a lady-in-waiting. However, King Henry soon wanted to end this marriage. He then married Catherine Howard, who was related to the Boleyn family.

Lady Rochford kept her job as a lady-in-waiting for Queen Catherine. In late 1541, Queen Catherine's past actions were discovered. Her private life was investigated. The Queen was held in her rooms and then placed under house arrest. People who were close to her were questioned. Lady Rochford was also questioned. She was involved in arranging meetings between the Queen and a man named Thomas Culpeper.

Downfall and Execution

During her time in the Tower of London, Lady Rochford was questioned. She was not tortured, but she became very unwell. By early 1542, she was declared insane.

Jane was sentenced to death by a special law. Her execution was set for 13 February 1542, the same day as Queen Catherine's execution.

Jane was executed and buried in the church of St Peter ad Vincula inside the Tower of London. She was buried near Queen Catherine, Anne Boleyn, and her husband George Boleyn.

In Books and TV

Lady Rochford has appeared in many books, especially those about Anne Boleyn and Catherine Howard. Some books show her as a difficult character, while others try to explain her actions.

She has also been shown in TV shows and movies. In the 1970 BBC series The Six Wives of Henry VIII, she was played by Sheila Burrell. In the 2008 film The Other Boleyn Girl, Juno Temple played her. In the TV series The Tudors, Joanne King played Jane. This version showed her marriage as unhappy. In Wolf Hall, Jessica Raine played her. This show suggested her actions were partly due to how Anne and George treated her.