Edmund Bonner facts for kids

Quick facts for kids The Right Reverend Edmund Bonner |

|

|---|---|

| Bishop of London | |

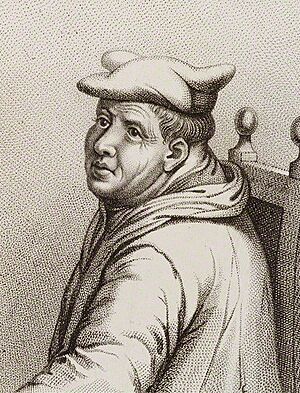

Edmund Bonner in a 19th-century engraving after 16th-century portrait

|

|

| Church | Catholic |

| Diocese | Diocese of London |

| Elected | 1539; 1553 |

| Reign ended | 1549; 1559 (twice deprived) |

| Predecessor | John Stokesley; Nicholas Ridley |

| Successor | Nicholas Ridley; Edmund Grindal |

| Other posts | Bishop of Hereford elected 27 November 1538 |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | c. 1519 |

| Consecration | 4 April 1540 by Stephen Gardiner |

| Personal details | |

| Born | c. 1500 Hanley, Worcestershire |

| Died | 5 September 1569 The Marshalsea |

| Buried | Southwark, London (initially) |

| Nationality | English |

| Denomination | Catholic |

| Parents | Edmund Bonner & Elizabeth Frodsham |

| Alma mater | Broadgates Hall, Oxford |

Edmund Bonner (around 1500 – September 5, 1569) was an important English bishop during a time of big religious changes. He served as the Bishop of London twice: first from 1539 to 1549, and then again from 1553 to 1559.

At first, Bonner helped King Henry VIII separate the Church of England from the Pope in Rome. But later, he disagreed with the Protestant changes made by the Duke of Somerset. Bonner then became a strong supporter of Catholicism. He became known as "Bloody Bonner" for his role in dealing with those who held different religious beliefs under Queen Mary I. He spent his final years as a prisoner under Queen Elizabeth I.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Edmund Bonner was born around the year 1500 in Hanley, Worcestershire. His mother was Elizabeth Frodsham. She was married to Edmund Bonner, who worked as a sawyer (someone who cuts wood).

He went to Broadgates Hall, which is now Pembroke College, Oxford. He earned a degree in civil and church law in 1519. Around the same time, he became a priest. In 1525, he received his doctorate in civil law.

Working for the King

In 1529, Bonner became a chaplain for Cardinal Thomas Wolsey. This job helped him get noticed by King Henry VIII and Thomas Cromwell, a powerful advisor. Even after Wolsey lost power, Bonner stayed loyal to him.

After Wolsey's death, Bonner began working for the King. In 1532, he was sent to Rome to help with the King's divorce. He tried to slow down the legal process against Henry in the Pope's court.

In 1533, Bonner was given the task of telling Pope Clement VII that King Henry wanted to appeal to a general church council. For his services, Bonner received several church positions. He was also made Archdeacon of Leicester in 1535.

Over the next few years, Bonner went on many important trips for the King. He tried to stop the Pope from calling a general council. In 1535, he went to North Germany to support what he called "the cause of the Gospel." He also wrote a foreword for a book that supported the King's power over the Pope. This pleased the Lutherans (early Protestants).

In 1538, Bonner became the ambassador to France. He was good at his job, but his bossy manner sometimes caused problems. He helped print the King's Great Bible in English in Paris. While in France, he was appointed to be the Bishop of Hereford. But because he was away, he couldn't officially take the role. In 1539, he was moved to become the Bishop of London. Bonner returned to England and was officially made bishop on April 4, 1540.

At this time, Bonner was seen as a strong supporter of King Henry's changes. He didn't protest against any of them. He wasn't a religious expert himself, but he agreed with the King's Act of the Six Articles. This law kept many traditional Catholic beliefs in England. One of his first jobs as Bishop of London was to try people who disagreed with these articles. He became known for being very strict, and many people in London disliked him. He became a strong supporter of traditional Catholic ways.

Religious Changes and Challenges

The death of King Henry VIII in 1547 changed everything for Bonner. He had always supported the King, even when Henry broke away from Rome. But Bonner had always kept his traditional Catholic beliefs.

When King Edward VI came to the throne, new Protestant changes were introduced by Protector Somerset and Archbishop Cranmer. Bonner disagreed with these changes. He believed that the King's power over the church was limited, especially since Edward was so young.

Under King Edward VI

Bonner resisted the new religious rules in 1547 and was sent to Fleet Prison. But he soon gave in and was released. He then spoke out against the government in Parliament. In 1549, he opposed the first Act of Uniformity and the new Book of Common Prayer.

When these laws passed, Bonner did not enforce them well. On September 1, 1549, he was ordered to preach that the young King Edward had full authority, just like an adult king. He did this, but he left out important parts. After a seven-day trial, he was removed from his position as bishop by a church court led by Archbishop Cranmer. He was then sent to the Marshalsea prison.

When Protector Somerset lost power, Bonner hoped to be freed. But the Protestant leaders stayed in charge. On February 7, 1550, Bonner's removal as bishop was confirmed. He was sentenced to stay in prison. He remained there until Queen Mary I came to the throne in 1553.

Under Queen Mary I

When Queen Mary I became queen, Bonner was immediately given back his job as Bishop of London. His removal was seen as unfair. He quickly worked to bring back Catholicism in his area. He had no problem accepting the Pope's authority again.

In 1554, Bonner visited his diocese to restore Catholic practices. This work was slow and difficult. To help, Bonner published a list of 37 "Articles to be enquired of" (questions to ask). But these caused so much trouble that they were temporarily removed.

Queen Mary's government believed that people who disagreed with the official religion should be dealt with by church courts. Since Bonner was Bishop of London, he had a big role in stopping religious disagreements. In 1555, he began the actions that led to his nickname "Bloody Bonner."

He was also chosen to remove Archbishop Cranmer from his church office in Oxford in 1556. The part Bonner played in these events made many people hate him. John Foxe, in his famous Book of Martyrs, wrote about Bonner:

- "This cannibal in three years space three hundred martyrs slew

- They were his food, he loved so blood, he spared none he knew."

However, some people who defend Bonner say he was just doing his official duty. They claim he had no control over the fate of those accused once they were declared to have wrong beliefs. They say he always tried to gently persuade them to return to the Catholic Church first. The Catholic Encyclopedia states that about 120 people were executed in his area, not 300. Many of these cases were forced on him by the King and Queen's Council. At one point, the Council even wrote to Bonner, saying he wasn't being strict enough.

Bonner's critics, like John Foxe and John Bale, painted a different picture. They said Bonner was eager to condemn people to death. Bale called him "the bloody sheep-bite of London" and "bloody Bonner."

Bonner also wrote important works during this time. These included books on priesthood and articles for his church visits. He also published Homelies (sermons) to be read in his diocese.

Under Queen Elizabeth I

After Queen Mary died, Elizabeth became queen. The Council ordered Bonner to give up his bishopric, but he refused. He said he would rather die. He was sent back to the Marshalsea prison on April 20, 1560.

For the next two years, Protestants often called for Bonner and other imprisoned bishops to be executed. In 1563, a new law was passed. Refusing the oath of royal supremacy (an oath recognizing the Queen as head of the church) a second time could lead to death. The bishops had already refused it once.

Thanks to the Spanish ambassador, action against the bishops was delayed. But in 1564, Bonner was charged for refusing the oath again. He questioned if the bishop who offered him the oath was properly appointed. A special law was passed to deal with this, and the charge against Bonner was dropped. For three years, he had to appear in court four times a year, only to be sent back to prison.

Bonner spent his last year in prison. He was known for being cheerful during his long imprisonment. Even John Jewel, the Bishop of Salisbury, described him as "a most courteous man and gentlemanly."

Bonner never stopped trying to convert others to Catholicism. He never regretted his actions under Queen Mary. Bishop Jewel wrote that Bonner visited other prisoners and called them his friends. Bonner died in the Marshalsea prison on September 5, 1569. He was buried secretly at midnight in St George's, Southwark, to avoid any angry crowds.

Bonner in Historical Memory

Some Catholic writers at the time considered Bonner and other bishops who died in prison to be martyrs. However, in English history, Bonner's name has often been strongly disliked.

Later historians have offered a more balanced view of Bonner. An Anglican historian, S. R. Maitland, described him as:

- "... a man, straightforward and hearty, familiar and humorous, sometimes rough, perhaps coarse, naturally hot tempered, but obviously (by the testimony of his enemies) placable and easily entreated..."

Lord Acton also noted in 1904 that while many people were executed in Bonner's diocese, this might have been because there were many Protestants in London and Essex. He also suggested that Bonner patiently dealt with many Protestants and tried his best to convince them to change their beliefs.

Twelve of Bonner's Homelies (sermons) were translated into the Cornish language by John Tregear. These are now the longest single work of traditional Cornish prose.

Legacy

- Bonner Street, Bethnal Green, East London

- Bonner Hall Bridge, Regent's Canal

- Bonner Road, Bethnal Green, East London

- Bonner Primary School, Stainsbury Street E2

Images for kids

| Church of England titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Edward Foxe |

Bishop of Hereford 1538–1539 |

Succeeded by John Skypp |

| Preceded by John Stokesley |

Bishop of London 1539–1549 |

Succeeded by Nicholas Ridley |

| Preceded by Nicholas Ridley |

Bishop of London 1553–1559 |

Succeeded by Edmund Grindal |

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |