Vestments controversy facts for kids

The Vestments Controversy was a big disagreement in the Church of England during the English Reformation. It was mainly about what clothes, called vestments, church leaders should wear.

The argument started when John Hooper, a bishop, refused to wear the special clothes required by the 1549 Book of Common Prayer and a church rule from 1550. He thought these clothes were too much like old Catholic traditions and not found in the Bible. This debate showed deeper worries within the Church of England about its identity, beliefs, and practices.

Contents

What Was the Vestments Controversy About?

This disagreement is also known as the vestiarian crisis. Sometimes, especially later, it was called the edification crisis. This name came from the debate about whether vestments, if they were considered "things indifferent" (meaning not essential for faith), should be allowed if they were "edifying" or helpful.

The idea of "edification" comes from the Bible (1 Corinthians 14:26). It means building up or improving the church. Some believed that the monarch (the king or queen) had the right to decide on church matters, including clothes, if it helped to "edify" the church.

The Controversy Under Edward VI

The argument first flared up during the reign of King Edward VI. John Hooper had been living outside England during King Henry VIII's time. He returned in 1548 from churches in Zürich that had changed a lot, removing many old church traditions. Hooper became a leading Protestant reformer in England.

In 1550, Hooper gave a series of Lenten sermons to the king. He spoke against the 1549 church rules that required new bishops to wear a cope and surplice and to swear an oath that mentioned "all saints." Hooper felt these were old Jewish and Catholic traditions that didn't belong in the Christian church.

Hooper was asked to explain his views to the Privy Council (the king's advisors) and the archbishop. They were mainly worried about whether Hooper would accept the king's authority over the church. Hooper seemed to reassure them, and he was soon offered the job of bishop of Gloucester.

However, Hooper refused the job because of the required vestments and the oath. This went against the Act of Uniformity 1549, which made refusing a church appointment a crime. So, Hooper was called before the king. The king understood Hooper's point of view, but the Privy Council did not.

A compromise was reached: vestments would be seen as adiaphora, or "things indifferent" – meaning they were not essential beliefs. Hooper could be ordained without them, but he had to allow others to wear them.

Still, the Bishop of London, Nicholas Ridley, who was supposed to perform the ordination, refused to do anything but follow the official rules. Ridley, though a reformer himself, seemed to have a problem with Hooper. He might have felt that reformers like Hooper, who had been in more radical churches abroad, were clashing with English clergy who had stayed with the established church.

The Privy Council repeated its decision, but Ridley argued that the monarch could require "indifferent things" without exception. The council became divided, and the issue dragged on. Hooper then argued that vestments were not indifferent because they encouraged hypocrisy and superstition.

The debate between Hooper and Ridley became very heated. Ridley focused on keeping order and authority in the church, while Hooper cared more about the vestments themselves.

Hooper and Ridley's Arguments

In a letter, Hooper argued that vestments should not be used because they are not "indifferent" and are not supported by the Bible. He said that church practices must either be clearly in the Bible or be "indifferent" things that the Bible implies are okay. He believed that if something couldn't be proven from the Bible, it wasn't a matter of faith.

Hooper also said that the Bible doesn't mention special clothes for clergy in the New Testament early church. He felt that priestly clothing in the Old Testament was a symbol that ended with Christ, who made all Christians spiritually equal.

Ridley disagreed with Hooper's strict demand for biblical origins. He pointed out that many common church practices are not mentioned in the Bible. Ridley also said that what the early church did isn't necessarily a rule for today.

Hooper also argued that an "indifferent thing" should be left to each person's choice. If it's required, it's no longer indifferent. Ridley countered that on "indifferent" matters, people should follow the church's authorities. He believed that refusing to obey showed disrespect for lawful authority. For Ridley, the debate was about who had the right to make rules, not just about the clothes. He said that things that have been misused should be fixed, not thrown away.

Marian Exiles and Vestments

During the reign of Queen Mary I, many Protestants, called Marian exiles, had to leave England. They went to places like Frankfurt, where they debated church rules and services. Even though they disagreed on many things, most of them, including those who supported the English prayer book, stopped using vestments while they were in exile.

When these exiles returned to England under Elizabeth I, this agreement didn't last. Many of those who had supported the prayer book in exile were given high positions in the church by Queen Elizabeth. They had to accept the use of vestments. However, many who had preferred the more "reformed" (simpler) church practices on the continent took lower positions. These people, who became leaders of the anti-vestment group, were freer to openly disobey the rules about clerical dress.

Many of the leaders against vestments under Elizabeth had spent time in Calvin's Geneva, where there were no vestments at all.

The Controversy Under Elizabeth I

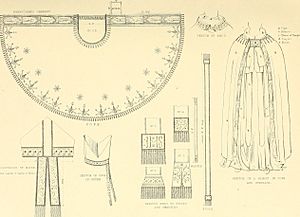

Elizabeth I wanted unity in her church. Her Act of Uniformity 1559 brought back the 1552 Prayer Book as the model, but it also said that vestments from the second year of Edward VI's reign (like the alb, cope, and chasuble) should be used again. Some exiles had even given up the surplice, so this was a big change for them. The queen took direct control over these rules.

Many clergy, including some who had been exiles, were unhappy. They wrote to important reformers like Peter Martyr Vermigli and Heinrich Bullinger for advice. Their advice was to accept the vestments but to preach against them. However, many English bishops, like Edmund Grindal and John Jewel, were reluctant to go against the queen, even if they had some sympathy for those who didn't want to conform. Archbishop Parker was also a major source of unhappiness for those who opposed vestments.

In 1563, a church meeting called the Convocation of 1563 voted on changes to the Prayer Book that would have removed vestments. These changes failed by just one vote. The queen supported Parker in keeping the rules of the 1559 Prayer Book.

On March 20, 1563, twenty clergy members asked the church commissioners to let them not use vestments. This group included important clergy in London. All the commissioners except Parker and Guest approved the petition, but Parker and Guest rejected it.

Parker then targeted Thomas Sampson and Humphrey, two nonconformist leaders. Sampson was quickly removed from his position in 1565 because he was directly under the queen's authority.

In March 1566, the church cracked down hard on those who wouldn't conform, especially in London. The London clergy were gathered at Lambeth Palace. They were told to appear in a square cap, gown, tippet, and surplice, and to follow the rules of the Prayer Book and the queen's orders. They had to say "yes" (volo) or "no" (nolo) in writing. Sixty-one said yes, but thirty-seven said no. Those who said no were immediately suspended from their jobs. They were given three months to change their minds before losing their jobs completely.

These punishments were based on Parker's Advertisements, which he had published to define church conformity. However, Parker hadn't gotten the queen's full approval for this mandate. The nonconformists reacted strongly, feeling persecuted. The term "Puritan" was first used around this time as a negative name for these nonconformists.

Protests in 1566

One of the clergy who said "no" was Robert Crowley, a vicar in London. Even though he was suspended, he ignored it. On April 23, Crowley stopped a funeral party at his church because some laymen (not clergy) were wearing surplices. He said the church was his and he wouldn't allow "superstitious rags of Rome" to enter. He succeeded in turning them away.

Other incidents happened too. At one church, a preacher spoke strongly against vestments, leading to a fight between parishioners who supported and opposed them. At another church, a member of the congregation stole the communion cup and bread because the minister used a wafer instead of ordinary bread.

Bishop Grindal found that another suspended lecturer, Bartlett, was still teaching without a license. Sixty women from the parish appealed to Grindal for Bartlett, but Grindal preferred to listen to "a half-dozen of their husbands."

Crowley's actions led to a complaint to Archbishop Parker. Crowley was put under house arrest but continued to insist he would not allow surplices. He was eventually fully removed from his position.

The "Literary War"

While under arrest, Crowley published a pamphlet called A Briefe Discourse Against the Outwarde Apparel of the Popishe Church (1566). This is sometimes called the first "Puritan manifesto." Crowley argued strongly against vestments, saying they were evil and that preachers were responsible to God, not to men. He also said that rulers were responsible for allowing such "vain toys."

Crowley agreed that vestments might be "indifferent" in theory, but he argued that when their use is harmful, they are no longer indifferent. He believed they were harmful because they encouraged superstition among simple people and confirmed the beliefs of Catholics. Crowley's writing was radical because he said that no human authority could go against God's disapproval of an abuse, even if the abuse came from something that was "indifferent."

In response, a pamphlet likely written by Parker argued that Crowley's ideas challenged the queen's authority and were like rebellion. This pamphlet said that vestments were good because they brought more respect to the sacraments. It also emphasized that disobeying authority was worse than the vestments themselves.

Another nonconformist pamphlet followed, arguing that vestments were "idolatrous abuses" and monuments of idolatry. It said that the Bible always had relevance to every question and activity. This pamphlet also argued that the monarch's authority did not extend to church matters beyond what the Bible allowed.

Letters from continental reformers like Bullinger were also published, sometimes by those who wanted to use them to support their own side. This "literary war" involved many pamphlets and letters, with both sides using biblical arguments and quoting famous reformers to support their views.

New Groups: Separatists and Presbyterians

After 1566, the most radical figures, called Separatists, began to organize illegal, secret church groups. They believed they had to separate from the official Church of England because it was too corrupt. When discovered, they often claimed they were not separatists but the true church.

Other opponents of vestments tried to change the church's structure to be more like Presbyterianism in the early 1570s. This system, supported by Calvin's successor, Theodore Beza, involved church governance by elders (presbyters) rather than bishops. This movement gained support from some Puritans.

A key moment was the publication of Admonition to Parliament in 1572, which was a founding document of English Presbyterianism. This led to a new debate between Archbishop John Whitgift and Thomas Cartwright. Whitgift agreed that vestments were not "indifferent" in themselves but insisted that the church had the authority to require them.

The issue of vestments, which started as a question of clothing, grew into a larger debate about the nature, authority, and legitimacy of the church's government. While Separatist Puritans continued to reject vestments, the bigger political issues about church power eventually overshadowed the original argument about clothes.

Images for kids

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |