John Wesley facts for kids

Quick facts for kids John Wesley |

|

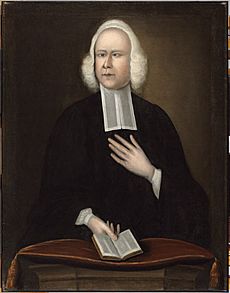

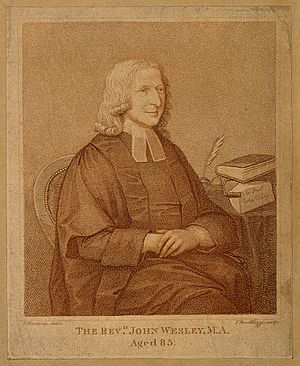

Portrait by George Romney (1789), National Portrait Gallery, London |

|

| Born | 28 June [O.S. 17 June] 1703 in Epworth, Lincolnshire, England |

|---|---|

| Died | 2 March 1791 (aged 87) in London, England |

| Nationality | English |

| Church | Church of England |

| Ordained | 1725 |

| Offices held |

President of the Methodist Conference

|

| Spouse |

Mary Vazeille

(m. 1751; separated 1758) |

| Parents | Samuel and Susanna Wesley |

John Wesley (born June 28, 1703 – died March 2, 1791) was an English church leader, religious thinker, and preacher. He led a big religious movement within the Church of England called Methodism. The groups he started became the main part of the independent Methodist movement we see today.

Wesley studied at Charterhouse School and Christ Church, Oxford. In 1726, he became a fellow at Lincoln College, Oxford. Two years later, he became an Anglican priest. At Oxford, he led the "Holy Club" with his brother Charles Wesley. This group focused on studying and living a very Christian life. George Whitefield was also a member.

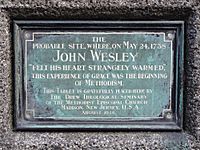

After working for two years in the Georgia colony in Savannah, Wesley returned to London. He joined a religious group led by Moravian Christians. On May 24, 1738, he had a powerful religious experience where he felt his "heart strangely warmed." After this, he left the Moravians and started his own ministry.

A big step for Wesley was to travel and preach outdoors, just like Whitefield. Unlike Whitefield's Calvinism, Wesley believed in Arminian doctrines. He traveled all over Great Britain and Ireland. He helped create and organize small Christian groups called "societies." These groups focused on personal faith and religious teaching. He also appointed traveling, unordained preachers, both women and men, to help these groups. Under Wesley's leadership, Methodists became important in social issues like ending slavery and improving prisons.

Wesley was not a formal theologian, but he taught about Christian perfection. He disagreed with Calvinism, especially the idea of predestination. His teachings were based on sacraments, believing that these helped believers become more holy. He taught that through faith, Christians could become more like Christ. He believed that in this life, Christians could reach a state where God's love "reigned supreme in their hearts." This would bring them both inner and outer holiness. Wesley's teachings, known as Wesleyan theology, still guide Methodist churches today.

Throughout his life, Wesley stayed part of the official Church of England. He believed the Methodist movement fit well within its traditions. Early in his ministry, many churches would not let him preach, and Methodists faced hard times. But later, he became widely respected. By the end of his life, people called him "the best-loved man in England."

Contents

- Early Life and Family

- Education and Early Ministry

- Journey to Savannah, Georgia

- Wesley’s “Aldersgate Experience”

- After Aldersgate: Working with the Moravians

- Challenges and Lay Preaching

- Methodist Chapels and Organization

- Ordination of Ministers

- Wesley's Beliefs and Teachings

- Personality and Daily Life

- Death and Legacy

- Literary Work

- Commemoration and Legacy

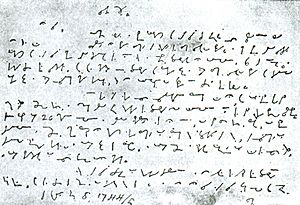

- Images for kids

- In Film and Theatre

- See also

Early Life and Family

John Wesley was born on June 28, 1703, in Epworth, England. He was the fifteenth child of Samuel Wesley and Susanna Wesley. His father, Samuel, was a poet and a church leader in Epworth. His mother, Susanna, was the daughter of a minister. She had nineteen children, but only nine lived past infancy. Both Samuel and Susanna became members of the Church of England as young adults.

Wesley's parents taught their children at home, which was common then. All the children, including the girls, learned to read very early. They were expected to learn Latin and Greek and memorize large parts of the New Testament. Susanna Wesley checked each child's learning before meals and evening prayers. The children were not allowed to eat between meals. Their mother also met with each child alone once a week for special religious lessons.

In 1714, when Wesley was 11, he went to Charterhouse School in London. There, he continued the studious and religious life he learned at home. A big event in his childhood was a fire at their home on February 9, 1709. Wesley was five years old. The roof caught fire, and sparks fell on the children's beds. Everyone got out except John, who was stuck upstairs. With the stairs burning and the roof about to fall, a neighbor helped him out a window. Wesley later used the phrase "a brand plucked out of the fire" from the Bible to describe this event. This story became part of his legend, suggesting he had a special purpose in life.

Education and Early Ministry

In June 1720, Wesley started at Christ Church, Oxford. After finishing his first degree in 1724, he stayed to study for his master's degree. On September 25, 1725, he became a deacon. This was a step toward becoming a fellow and teacher at the university. On March 17, 1726, Wesley was chosen as a fellow of Lincoln College. This gave him a room and a regular salary. While studying, he taught Greek and philosophy. He also lectured on the New Testament.

In August 1727, after getting his master's degree, Wesley went back to Epworth. His father needed his help in a nearby church. Wesley became a priest on September 22, 1728. He worked as a church curate for two years. During this time, he read books by Thomas à Kempis and William Law. These books made him think deeply about God's laws and how to live a holy life. He decided to follow God's laws as strictly as possible, believing this would lead to salvation. He lived a very disciplined life, studied the Bible, and gave money to the poor. He wanted to achieve "holiness of heart and life."

In November 1729, Wesley returned to Oxford to keep his position as a junior fellow.

The Holy Club

While Wesley was away, his younger brother Charles started a small club at Christ Church. This group was for studying and living a very Christian life. When Wesley returned, he became the leader. The group grew in size and commitment. They met daily for prayer, psalms, and reading the Greek New Testament. They prayed often throughout the day. They also took Communion every Sunday, even though the church only required it three times a year. They fasted on Wednesdays and Fridays.

In 1730, the group started visiting prisoners in jail. They preached, taught, and helped prisoners who owed money. They also cared for the sick. Many people at Oxford did not like Wesley's group. They called them "religious fanatics." People at the university mockingly called them the "Holy Club." This name was meant to make fun of them. The group was also called "Methodist" by others. Wesley later used this name to describe his followers.

Wesley wanted to be truly holy inside. He kept detailed records of his daily activities. He noted how well he kept his resolutions and how devoted he felt each hour. He also saw the criticism he received as a sign of being a true Christian. He wrote that a person was not truly saved "Till he be thus contemned."

Journey to Savannah, Georgia

On October 14, 1735, Wesley and his brother Charles sailed from England to Savannah. They went at the request of James Oglethorpe, who founded the Georgia colony. Oglethorpe wanted Wesley to be the minister for the new Savannah parish.

During the voyage, the Wesleys met Moravian settlers. Wesley was impressed by their strong faith. Once, during a storm, the English passengers panicked. But the Moravians calmly sang hymns and prayed. This made Wesley feel that the Moravians had an inner strength he lacked. Their deep personal faith greatly influenced Wesley and his later Methodist teachings.

Wesley arrived in Georgia in February 1736. He lived in the parsonage for a year. He saw his mission in Georgia as a chance to bring back "early Christianity." His main goal was to preach to Native American people. But there were not enough clergy in the colony, so he mostly worked with European settlers in Savannah. While his time there is often seen as a failure compared to his later success, Wesley did gather a group of devoted Christians. They met in small religious societies. Also, more people attended Communion during his two years as a priest at Christ Church.

However, Wesley's ministry in Georgia was not easy. It ended unhappily after he developed feelings for a young woman named Sophia Hopkey. He hesitated to marry her because he felt his main job was to be a missionary to Native Americans. He was also interested in the idea of priests not marrying. After she married someone else, Wesley felt her religious devotion lessened. He eventually left the colony on December 22, 1737, and returned to England.

One important thing Wesley did in Georgia was publish a Collection of Psalms and Hymns. This was the first Anglican hymnal published in America. It was the first of many hymn books Wesley would publish. It included five hymns he translated from German.

Wesley’s “Aldersgate Experience”

Wesley returned to England feeling sad and defeated. At this point, he turned to the Moravians. Both he and Charles got advice from a young Moravian missionary, Peter Boehler. Wesley's famous "Aldersgate experience" happened on May 24, 1738. He was at a Moravian meeting in Aldersgate Street, London. He heard someone read from Martin Luther's introduction to the Epistle to the Romans in the Bible. This moment completely changed his ministry. Earlier that day, he had heard a choir singing Psalm 130 at St Paul's Cathedral.

Still, Wesley felt down when he went to the evening service on May 24. But during the reading, he felt his "heart strangely warmed." He felt a deep trust in Christ for his salvation. He felt that Christ had taken away his sins and saved him.

A few weeks later, Wesley preached about personal salvation through faith. He then preached about God's grace being "free for all." This moment is seen as a turning point. Daniel L. Burnett says: "The importance of Wesley's Aldersgate Experience is huge... Without it, the names of Wesley and Methodism would likely be nothing more than obscure footnotes in the pages of church history." This event is often called Wesley's "Evangelical Conversion." May 24 is celebrated in Methodist churches as Aldersgate Day.

After Aldersgate: Working with the Moravians

Wesley joined the Moravian society in Fetter Lane, London. In August 1738, he traveled to Germany to visit Herrnhut, the Moravian headquarters. When he returned to England, Wesley made rules for the groups within the Fetter Lane Society. He also published a collection of hymns for them. He met often with these groups in London. However, he did not preach much in 1738 because most churches would not let him.

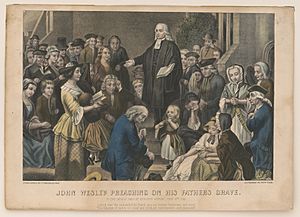

Wesley's friend, the preacher George Whitefield, was also not allowed to preach in churches in Bristol. In February 1739, Whitefield went to a nearby village, Kingswood, and preached outdoors to miners. Wesley was unsure about doing this. But he overcame his doubts and preached outdoors for the first time near Bristol in April 1739.

Wesley did not like the idea of preaching outdoors at first. He thought it was "almost a sin." But he soon realized that outdoor services reached many people who would not go into churches. From then on, he preached wherever people would gather. He even used his father's tombstone in Epworth as a pulpit. Wesley continued this for fifty years. He preached in churches when invited, and in fields, halls, cottages, and chapels when churches would not have him.

In late 1739, Wesley separated from the Moravians in London. He felt they were teaching wrong ideas. So, he decided to form his own group of followers. He wrote, "Thus, without any previous plan, began the Methodist Society in England." He soon started similar groups in Bristol and Kingswood. Wesley and his friends made many new followers wherever they went.

Challenges and Lay Preaching

From 1739 onwards, Wesley and the Methodists faced difficulties from church leaders and officials. Even though Wesley was an Anglican priest, many other Methodist leaders were not. Wesley also did not follow many Church of England rules about church areas and who could preach. This was seen as a threat to the established church. Clergy attacked them in sermons and writings. Sometimes, angry crowds attacked them too. Wesley and his followers kept working among those who were ignored and in need. People accused them of teaching strange ideas and causing religious trouble. They were called fanatics who misled people.

Wesley felt that the church was failing to call people to change their ways. He believed many clergy were corrupt and that people were suffering in their sins. He felt God had given him a mission to bring about a revival in the church. He believed no opposition could stop this divine mission. He put aside his own strict ideas about church rules and traditions to do God's work.

Wesley realized that he and the few clergy working with him could not do all the work needed. So, as early as 1739, he started allowing local preachers. These were men who were not ordained by the Anglican Church. They preached and did pastoral work. This use of non-clergy preachers was a key reason Methodism grew so much.

Methodist Chapels and Organization

As his groups needed places to worship, Wesley began to provide chapels. The first was in Bristol, called the New Room. Then came "The Foundery" in London, and later Wesley's Chapel. The Foundery was an old building that used to make brass guns. It had been empty for 23 years after an explosion.

The Bristol chapel, built in 1739, was first managed by a group of people. But a large debt grew, so Wesley's friends asked him to take full control. He became the only manager. Following this, all Methodist chapels were put under his care. Later, he transferred control of them to a group of preachers called the "Legal Hundred."

To keep order among members, Wesley started giving out tickets. These tickets had members' names and were renewed every three months. Those who were not living up to the standards did not get new tickets and quietly left the group.

When chapel debts became a problem, it was suggested that one member out of twelve collect money from the other eleven. This led to the Methodist class-meeting system in 1742. To keep bad behavior out of the groups, Wesley started a trial period for new members. He also visited each group regularly. As the number of groups grew, Wesley could not visit everyone. So, in 1743, he wrote a set of "General Rules" for the "United Societies." These rules became the basis of the Methodist Discipline, which is still used today.

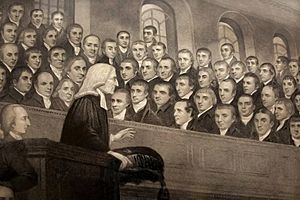

Wesley built the foundation for what is now the Methodist Church organization. Over time, a system of societies, circuits, quarterly meetings, annual conferences, classes, and bands developed. Locally, there were many societies grouped into circuits. Traveling preachers were assigned to these circuits for two-year periods. Circuit leaders met every three months. Conferences with Wesley and traveling preachers were held yearly to discuss beliefs and rules for the whole movement. Classes of about a dozen members met weekly for spiritual support.

In 1744, John and Charles Wesley, along with other clergy and lay preachers, met in London. This was the first Methodist conference. Later, the Conference, with Wesley as its president, became the main governing body of the Methodist movement. Two years later, Wesley appointed "helpers" to specific circuits. Each circuit had at least 30 preaching stops a month. Wesley believed that preachers worked better if they moved to a new circuit every year or two. He called this the "itinerancy" and insisted his preachers follow this rule.

John Wesley had strong ties to the North West of England. He visited Manchester at least fifteen times between 1733 and 1790. In 1781, Wesley opened a chapel on Oldham Street in Manchester.

Ordination of Ministers

As the Methodist groups grew, they started to look more like a church system. The difference between Wesley and the Church of England became wider. Some of his preachers and groups wanted to separate from the Church of England. But his brother Charles strongly opposed this. Wesley himself refused to leave the Church of England. He believed Anglicanism was "nearer the Scriptural plans than any other in Europe." In 1745, Wesley wrote that he would do anything his conscience allowed to live in peace with the clergy. But he would not give up the idea of salvation by faith. He would not stop preaching, or break up the societies, or stop lay members from preaching.

In 1746, Wesley read a book that convinced him that apostolic succession (the idea that church authority comes from the apostles) could be passed down by priests, not just bishops. He wrote that he was "a scriptural episkopos (bishop) as much as many men in England."

In 1784, Wesley felt he could no longer wait for the Bishop of London to ordain ministers for the American Methodists. After the American War of Independence, the Church of England was no longer the official church in the United States. So, Wesley ordained Thomas Coke as a superintendent for Methodists in the United States. Coke was already a priest in the Church of England. Wesley also ordained Richard Whatcoat and Thomas Vasey as priests. They sailed to America with Coke. Wesley wanted Coke and Francis Asbury to ordain others in the new Methodist Episcopal Church in the United States.

His brother Charles was worried by these ordinations. He begged Wesley to stop. But Wesley replied that he had not left the church and did not plan to. However, he said he must save as many souls as he could while alive. Even though Wesley was happy that American Methodists were free, he advised his English followers to stay in the established church.

Wesley's Beliefs and Teachings

A scholar named Albert Outler said that Wesley developed his religious beliefs using a method called the Wesleyan Quadrilateral. In this method, Wesley believed that the main part of Christianity was in the Bible (Scripture). He thought the Bible was the only true source for religious ideas. He even called himself "a man of one book," even though he read a lot.

However, Wesley also believed that religious ideas must agree with Christian traditional teachings. So, tradition was the second part of his method. Wesley also thought that faith had to be experienced personally. This meant that if something was truly God's truth, Christians would feel it in their own lives. And finally, every belief had to be explained using reason. He did not separate faith from reason. But Wesley always said that tradition, experience, and reason must always be guided by the Bible.

Wesley often spoke and wrote about several key ideas:

- Prevenient Grace: This is God's grace that comes before we even know it. It helps all people be able to believe in Christ and be saved. Unlike some others, Wesley did not believe in predestination. He thought God wanted everyone to be saved.

- Personal Salvation by Faith: Wesley believed that salvation comes from personal faith in Christ.

- Witness of the Spirit: He described this as an "inward impression" where God's Spirit tells believers that they are God's children. This idea came from Bible verses like Romans 8:15–16.

- Entire Sanctification: Wesley taught that Christians could become "perfect in love" after they were saved, and before they died. He avoided the term "sinless perfection" because it could be confusing. Being "perfect in love" meant that a believer's actions would be guided by a strong desire to please God. It also meant living with a main focus on caring for others. This love for God and others would be "a fulfillment of the law of Christ."

Supporting Arminianism

Wesley often got into arguments as he tried to change church practices. His most famous argument was about Calvinism. His father believed in Arminian ideas. Wesley came to his own similar conclusions in college. He strongly disagreed with Calvinist ideas like predestination, which he called "blasphemous." He said it made "God worse than the devil." His way of thinking is now called Wesleyan Arminianism.

In contrast, Whitefield believed in Calvinism. Whitefield disagreed with Wesley's Arminian ideas, but they remained friends, though sometimes with tension. When Wesley preached a sermon attacking Calvinism in 1739, Whitefield asked him not to publish it. But Wesley published it anyway. The two men then separated their work in 1741.

Whitefield and others became the founders of Calvinistic Methodism. But Whitefield and Wesley soon became friendly again. Their friendship lasted even though they took different paths. When someone asked Whitefield if he thought he would see Wesley in heaven, Whitefield joked, "I fear not, for he will be so near the eternal throne and we at such a distance, we shall hardly get sight of him."

In 1770, the argument started again, becoming very heated. Wesley began publishing The Arminian Magazine in 1778. He said he did this not to convince Calvinists, but to protect Methodists. He wanted to teach the truth that "God willeth all men to be saved."

Fighting Against Slavery

Later in his life, Wesley strongly supported the movement to end slavery. He spoke out and wrote against the slave trade. Wesley called slavery "the sum of all villainies." In 1774, he wrote a powerful paper called Thoughts Upon Slavery. He wrote, "Liberty is the right of every human creature, as soon as he breathes the vital air." Wesley also influenced William Wilberforce, who was important in ending slavery in the British Empire.

Because of Wesley's anti-slavery message, a young African American named Richard Allen became a Christian in 1777. Allen later founded the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME) in 1816, following Methodist traditions.

Supporting Women Preachers

Women played an active role in Wesley's Methodism. They were encouraged to lead classes. In 1761, he informally allowed Sarah Crosby, one of his followers, to preach. One time, over 200 people came to a class she was supposed to teach. Crosby felt she had to preach instead. She wrote to Wesley for advice. He told her she could continue preaching as long as she avoided acting too much like a formal preacher. Between 1761 and 1771, Wesley gave Crosby and other women detailed instructions on how they could preach.

In 1771, Mary Bosanquet wrote to Wesley to defend her and Sarah Crosby's preaching work. Her letter is seen as the first full defense of women preaching in Methodism. She argued that women should be able to preach if they felt a special call from God. Wesley accepted her argument. From 1771, he formally allowed women to preach in Methodism.

Personality and Daily Life

Wesley traveled widely, usually on horseback. He preached two or three times every day. One writer says Wesley rode 250,000 miles, gave away a lot of money, and preached over 40,000 sermons. He started societies, opened chapels, and trained preachers. He also helped with charities, cared for the sick, and oversaw orphanages and schools.

Wesley ate a vegetarian diet. Later in life, he stopped drinking wine for health reasons. He enjoyed music concerts, especially by Charles Avison. After a concert in 1758, Wesley wrote in his journal that the audience was very serious during Handel's Messiah. He said it was even better than he expected.

Wesley is described as "rather under the medium height, well proportioned, strong, with a bright eye, a clear complexion, and a saintly, intellectual face." He married Mary Vazeille in 1751 when he was 48. She was a widow with four children. They had no children together, and their marriage was not happy. Mary left him several times before their final separation. Wesley wrote in his journal, "I did not forsake her, I did not dismiss her, I will not recall her."

When George Whitefield died in 1770, Wesley wrote a sermon praising him. He acknowledged their differences but said, "In these we may think and let think; we may 'agree to disagree.'" Wesley may have been the first to use "agree to disagree" in print in its modern meaning.

Wesley was very ill during a visit to Lisburn, Ireland, in June 1775. People thought he would die. But after prayers were said for "another fifteen years," he recovered.

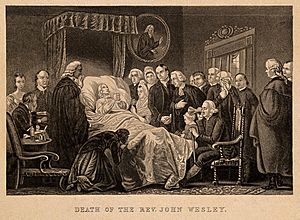

Death and Legacy

Wesley's health got much worse near the end of his life, and he stopped preaching. He died on March 2, 1791, at the age of 87. As he was dying, his friends gathered around him. Wesley held their hands and kept saying, "Farewell, farewell." At the very end, he said, "The best of all is, God is with us." He lifted his arms and repeated these words. He was buried at his chapel on City Road, London.

Because he gave so much to charity, Wesley died without much money. He left behind 135,000 members and 541 traveling preachers under the name "Methodist." People say that when John Wesley was buried, he left behind a good library of books, a well-worn clergyman's robe, and the Methodist Church.

Literary Work

Wesley wrote, edited, or shortened about 400 publications. Besides religious topics, he wrote about music, marriage, medicine, abolitionism, and politics. Wesley was a clear and strong writer. Between 1746 and 1760, he put together several books of his sermons, called Sermons on Several Occasions. His Forty-Four Sermons and Explanatory Notes Upon the New Testament (1755) are important Methodist books. Wesley was a powerful preacher. He usually preached without notes and for a short time, but sometimes for a very long time.

In his Christian Library (1750), he wrote about mystics like Macarius of Egypt and Blaise Pascal. This shows how Christian mysticism influenced his ministry.

Wesley's writings were first collected by himself in 32 volumes. His main prose works are published in seven volumes. The Poetical Works of John and Charles Wesley were published in 13 volumes.

Besides his sermons and notes, his Journals are also very important. These were published in 20 parts between 1740 and 1789. Other works include The Doctrine of Original Sin (1757), An Earnest Appeal to Men of Reason and Religion (1743), which defended Methodism, and a Plain Account of Christian Perfection (1766).

Wesley's Sunday Service was his version of the Book of Common Prayer for American Methodists. In his Watchnight service, he used a prayer now known as the Wesley Covenant Prayer, which is perhaps his most famous contribution to Christian worship. He was also a well-known hymn-writer and translator.

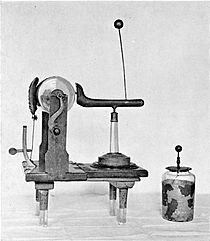

Wesley also wrote about science and medicine. For example, he wrote The Desideratum (1759), which was about electricity. He also wrote Primitive Physic, Or, An Easy and Natural Method of Curing Most Diseases.

Commemoration and Legacy

Wesley is still the main religious influence for Methodists around the world. The Methodist movement has 75 million followers in over 130 countries. His teachings also form the basis for the Holiness movement, which includes churches like the Free Methodist Church, the Church of the Nazarene, and the Salvation Army. Pentecostalism and parts of the Charismatic movement also grew from these teachings. Wesley's call for personal and social holiness continues to inspire Christians today.

He is remembered in the Calendar of Saints of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America on March 2, along with his brother Charles. The Wesley brothers are honored on March 3 in the Calendar of Saints of the Episcopal Church. They are also honored on May 24 (Aldersgate Day) in the Church of England's Calendar.

In 2002, Wesley was ranked number 50 on the BBC's list of the 100 Greatest Britons.

Wesley's house and chapel, which he built in 1778 in London, are still standing today. The chapel has a busy church, and there is a Museum of Methodism in the basement.

Many schools, colleges, hospitals, and other places are named after Wesley. In 1831, Wesleyan University in Connecticut was the first higher education school in the United States named after him.

A copy of the house where Wesley lived as a boy was built in the 1990s in Lake Junaluska, North Carolina. This was part of a group of buildings for the World Methodist Council. It included a museum with letters written by Wesley and a pulpit he used. The museum closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Its items were moved to Bridwell Library at Perkins School of Theology in Dallas, Texas.

Images for kids

-

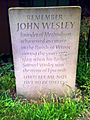

"Remember John Wesley", Wroot, near Epworth.

-

Statue of Wesley outside Wesley Church in Melbourne, Australia.

-

Stained glass window honoring the Wesleys and Asbury, at Lake Junaluska, North Carolina.

-

John Wesley preaching in Moorfields in 1738, stained glass in St Botolph's, Aldersgate.

In Film and Theatre

In Film

In 1954, the British Methodist Church and J. Arthur Rank made a film called John Wesley. It told the story of Wesley's life, with Leonard Sachs playing Wesley.

In 2009, a bigger movie called Wesley was released by Foundery Pictures. Burgess Jenkins played Wesley, and the film was directed by John Jackman.

In Musical Theatre

In 1976, a musical called Ride! Ride! premiered in London. It was composed by Penelope Thwaites and written by Alan Thornhill. The musical is based on a true story from Wesley's life about a young woman named Martha Thompson who was put in a mental hospital. The show has been performed many times since then.

See also

In Spanish: John Wesley para niños

In Spanish: John Wesley para niños

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |