Linotype machine facts for kids

The Linotype machine was a special printing machine that could create a whole line of metal letters at once. It was a big step forward from setting type by hand, where workers had to pick out one metal letter at a time. The name "Linotype" comes from "line-o'-type," because it made an entire line of text in one go!

This amazing machine was used a lot in newspapers, magazines, and for posters from the late 1800s until the 1970s and 1980s. It made printing much faster and easier.

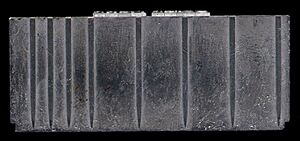

Here's how it generally worked: An operator would type on a keyboard. The machine would then gather tiny molds, called matrices, for each letter. These molds would line up to form a word or sentence. Then, hot, melted metal was poured into these molds to create a single, solid piece of metal with the whole line of text on it. This piece was called a slug. After the slug was made, the matrices were automatically put back in their places, ready to be used again.

The Linotype machine changed newspaper publishing forever. It meant that fewer people could set up many pages of text every day. Ottmar Mergenthaler invented the Linotype in 1884, with help from James Ogilvie Clephane, who provided money to make it a real product.

The Story of Linotype

The inventor of the Linotype machine was a German clock maker named Ottmar Mergenthaler. He moved to the United States in 1872. In 1876, a man named James O. Clephane and his friend Charles T. Moore asked Mergenthaler for a faster way to print legal documents.

By 1884, Mergenthaler had a brilliant idea: a machine that could put together metal letter molds (matrices) and then pour hot metal into them, all in one go. His first try showed it was possible, and a new company was started.

Mergenthaler kept improving his invention. In July 1886, the very first Linotype machine used for business was set up at the New York Tribune newspaper office. It was immediately used to print the daily paper and a big book. That book, called The Tribune Book of Open-Air Sports, was the first book ever made using the new Linotype method!

At first, the Mergenthaler Linotype Company was the only one making these line-casting machines. But over time, other companies started making similar ones. For example, The Intertype Company began making the Intertype machine around 1914. It was very similar to the Linotype and even used the same matrices.

Newspapers slowly stopped using Linotype machines in the 1970s and 1980s. They were replaced by newer technologies like phototypesetting and later, computer systems. Today, very few newspapers still use Linotype. The Saguache Crescent in the United States and Le Démocrate de l'Aisne in Western Europe are some of the last ones.

How the Linotype Machine Works

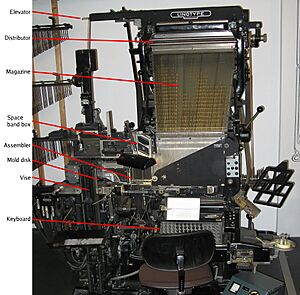

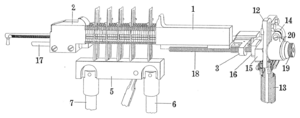

The Linotype machine has four main parts that work together:

- Magazine: This is where the letter molds (matrices) are stored.

- Keyboard: This is where the operator types the text.

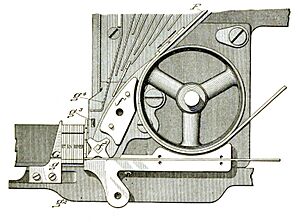

- Casting Mechanism: This part melts metal and creates the line of type.

- Distribution Mechanism: This part puts the matrices back in their correct places.

The operator uses the keyboard to type out lines of text. The other parts of the machine work automatically once a line is finished. Some Linotype machines could even read text from a paper tape, which meant they could print even faster!

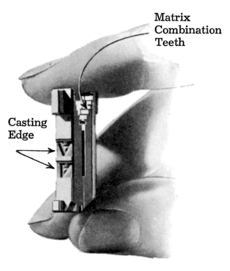

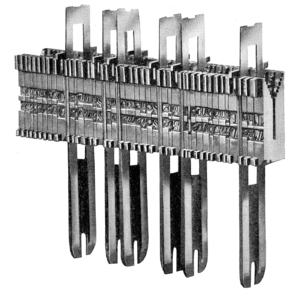

Matrices: The Letter Molds

Each matrix is a small metal piece with the shape of a letter, number, or symbol carved into it. Think of it like a tiny cookie cutter for a letter. These matrices are used to create the metal slugs.

Many matrices have two letter shapes on them. For example, one side might have a regular (Roman) letter, and the other side might have an italic (slanted) or bold version of that letter. The operator could choose which version to use.

When you look at a Linotype matrix, the letter shape is carved *into* it, not raised. This is because it's a mold. The metal slug that comes out of the mold will have the letter raised, ready for printing.

The Magazine Section

The magazine is like a storage box for all the matrices. It's a flat box with many thin walls that create "channels." Each channel holds matrices for a specific character, like all the "a"s or all the "b"s. Most magazines have 90 channels.

Each magazine holds a specific font (a style and size of type). If the operator needed a different font, they would switch to a different magazine. Some Linotype machines could hold several magazines at once, making it easy to change fonts.

To keep the matrices moving smoothly, it was very important to keep the machine clean and free of oil. If oil got into the matrix path, it could cause matrices to get stuck or come out in the wrong order, which would slow down printing. Operators had to be very careful with maintenance!

Keyboard and Composing

In this section, the operator types the text. Every time a key is pressed, a matrix for that character is released from the magazine. The matrix then travels down channels and lines up with others in a special area called the assembler.

When the operator needs a space between words, they press a special lever. This releases a spaceband. Spacebands are different from matrices because they can expand to make the line of text fit perfectly.

Once a line is typed and ready, the operator presses a "casting lever." This sends the line of matrices and spacebands to the casting section. While the machine is busy casting that line, the operator can already start typing the next one!

The Keyboard Layout

The Linotype keyboard has 90 keys. The keys are usually arranged by color: black keys on the left for small letters, white keys on the right for capital letters, and blue keys in the middle for numbers, punctuation, and other symbols. There's no "shift" key like on a modern computer keyboard.

The letters are arranged so that the most common ones are easy to reach. For example, the first two columns have letters like e, t, a, o, i, n, s, h, r, d, l, u. If an operator made a mistake, it was often faster to just finish the line with these common letters (creating nonsense words like "etaoin shrdlu") and then remove the bad line later.

Spacebands for Justification

In printing, "justified text" means that all lines are the same width, with spaces between words stretching or shrinking to make this happen. Linotype machines did this using spacebands. A spaceband is made of two metal wedges. When these wedges are pushed up, they expand, making the space wider.

Spacebands are stored separately from the matrices because they are too large to fit in the magazine. They are released one at a time when the operator presses the spaceband lever.

The Assembler

As matrices and spacebands are released, they travel along a moving belt into the assembler. The assembler is a rail where the matrices and spacebands line up side by side. One end of the assembler is set to the exact width the line of text needs to be.

When the operator thinks the line is long enough, they send it to the casting section. The rest of the process for that line happens automatically, allowing the operator to start typing the next line right away.

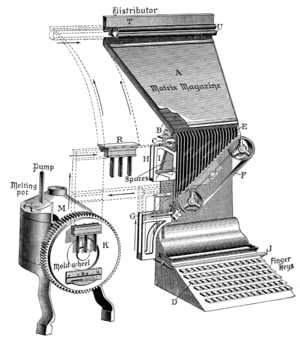

The Casting Section

The casting section is where the magic happens: the metal slug is created! This part of the machine starts working automatically once the operator sends a completed line. The whole process of casting a slug takes less than nine seconds.

The metal used for casting is a special mix, mostly lead (about 85%), with some antimony and tin. This mix creates a strong slug that can be used to print many thousands of copies before it starts to wear out.

The metal is kept melted in a pot at a very precise temperature (around 535°F or 279°C). As the metal is heated, some impurities rise to the top and form a "dross" that needs to be removed.

Justifying the Line

After the line of matrices and spacebands leaves the assembler, it moves to the justification vise. This vise has two jaws that are set to the exact width of the line needed. The spacebands then expand to make the line fit tightly between these jaws. This tight fit is super important because it stops the hot, melted metal from leaking out when the slug is cast.

If the operator didn't type enough characters for the line, it won't justify correctly. A safety system in the machine detects this and stops the casting process. This is a good thing! Without it, hot metal could spray out, which would be a big mess and dangerous for the operator.

Making the Slug

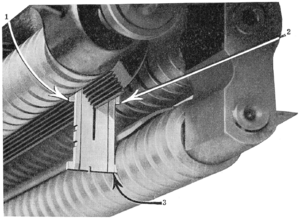

The justified line of matrices is pressed against a mold disk. This disk has rectangular openings that match the size of the slug that will be made. Behind the mold disk is a pot of melted metal.

Just before casting, the mold disk moves forward and presses tightly against the matrices. Then, the pot tilts, and a plunger pushes the melted metal into the mold opening. The hot metal flows into the carved shapes on the matrices and fills the mold, creating a solid metal slug with the letters raised on top. The mold disk is often cooled to help the slug harden quickly.

Once the slug is solid, the mold disk rotates. As it moves, the slug is trimmed by sharp knives to make sure it's the correct height and thickness for printing. Finally, a set of blades pushes the finished slug out of the mold. The slug then drops into a tray, ready to be used for printing.

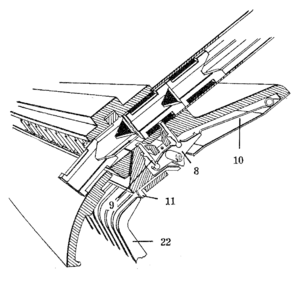

The Distribution Mechanism

One of the most clever parts of the Linotype machine is how it automatically puts the matrices back where they belong. This is done by the distributor.

After a slug is cast, the matrices are lifted up to the top of the machine, to the distributor. The spacebands are separated here and sent back to their own storage box.

The matrices have a special pattern of teeth at the top. These teeth allow them to hang from the distributor bar. The distributor bar also has a pattern of cut-away teeth. As each matrix travels along the bar, it will hang on until it reaches the exact spot where its teeth match the cut-away sections on the bar. At that point, it loses its support and drops down into its correct channel in the magazine, ready to be used again!

Special Matrices: Pi Characters

Sometimes, printers need to use very unusual characters, like special symbols or fractions, that aren't in the main magazine. These are called pi characters. On a Linotype machine, a pi matrix has all its teeth, so it won't drop into any of the regular magazine channels. Instead, it travels all the way to the end of the distributor bar and drops into a special tube called the pi chute. These characters are then collected in a "sorts stacker" for later use.

See also

- Ottmar Mergenthaler

- Monotype System

- Saguache Crescent

- Etaoin shrdlu

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |