Proto-cuneiform facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Proto-cuneiform |

|

|---|---|

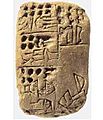

| [[Image:Tableta_con_trillo.png|]]

Kish Tablet

|

|

| Type | Ideographic |

| Spoken languages | Unknown, possibly Sumerian |

| Time period | c. 3500–2900 BC |

| Child systems | Cuneiform |

| ISO 15924 | Pcun |

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. | |

The proto-cuneiform script was an early way of writing that appeared in Mesopotamia, a region in the Middle East. It was a very old form of writing that later grew into the famous cuneiform script. Cuneiform was used in Mesopotamia during its Early Dynastic I period.

This writing system started from a simpler method that used small clay "tokens" to keep track of things. These tokens had been used for thousands of years before proto-cuneiform. We know that later cuneiform was used to write the Sumerian language. However, we are not sure what language people spoke when they used proto-cuneiform.

Contents

How Did Proto-Cuneiform Begin?

Around 9,000 years ago, people in the ancient Near East started using small clay tokens. These tokens helped them keep records, like how many animals they had or how much grain they stored. Over time, these tokens changed. They became marked, and then people started putting them inside hollow clay balls called "bullae."

Scientists believe these tokens and bullae were the first steps toward proto-cuneiform. Another writing system, Proto-Elamite, also developed around the same time. Many tokens have been found in Susa, an important city in a region called Elam. Even after proto-cuneiform appeared, people still used these older tokens.

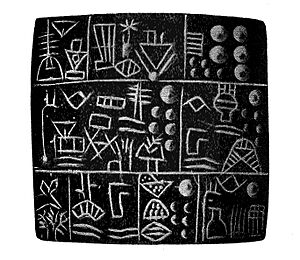

The very first proto-cuneiform tablets found are mostly "numerical." This means they mainly show lists of numbers with simple signs like circles or triangles. These tablets were often sealed, like a signature. Most of these early tablets were found in Susa and Uruk.

When Was Proto-Cuneiform Used?

Proto-cuneiform first appeared around 3300 BC, during a time known as the Uruk IV period. It continued to be used through the Uruk III period. The writing slowly changed over time, with signs combining or looking different. It started in Uruk and then spread to other places like Jemdet Nasr.

Around 2900 BC, the standard cuneiform script began to be used to write the Sumerian language. Only about 400 tablets from this early cuneiform period have been found, mostly from Ur. So, it took about 5,000 years for writing to develop from simple tokens to full cuneiform. This is about the same amount of time that has passed since cuneiform was first used!

What Language Did It Represent?

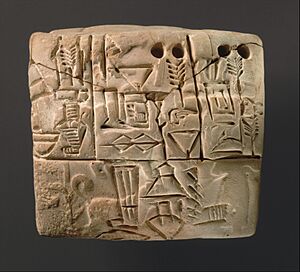

[[File:Pictographs Recording the Allocation of Beer (London, England).jpg|thumb|This proto-cuneiform tablet records how much beer was given out.]] Experts have long debated when the Sumerian people arrived in Mesopotamia. Many changes happened in Mesopotamia around the same time the Sumerian language first clearly appeared.

Proto-cuneiform tablets do not clearly show what spoken language they represent. This has led to many guesses, but many people think it was an early form of Sumerian.

Where Were Proto-Cuneiform Tablets Found?

About 4,000 proto-cuneiform texts have been found in Uruk, which is the largest collection. These tablets are mostly from two different styles. The older tablets (from building level IV) have more natural-looking pictures and were written with a pointed tool. The newer tablets (from building level III) have more abstract designs and were made with a blunt tool. These styles match the Late Uruk (around 3100 BC) and Jemdet Nasr (around 3000 BC) periods.

Many of these tablets were later used as filler when new buildings were constructed. It seems people thought these records were only useful for a short time and then threw them away.

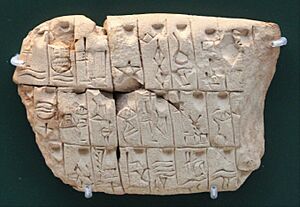

Smaller numbers of tablets were found in places like Jemdet Nasr, Umma, and Kish. These tablets are often in better condition. Some have ended up in museums and private collections around the world. For example, a famous tablet called the "Kish tablet" was found in the 1920s. A copy of it is in the Ashmolean Museum, and the original is in the Baghdad Museum.

Some tablets were sealed using a cylinder seal, which was like a rolling stamp.

How Do We Understand Proto-Cuneiform?

To understand an unknown writing system, scholars usually need to know the language it represents, or have texts that are written in two languages. Proto-cuneiform was different. It wasn't a full writing system for stories or poems. Instead, it was a special way to keep economic records, like lists of items. Because these texts were very simple and always about the same things, it was possible to figure them out.

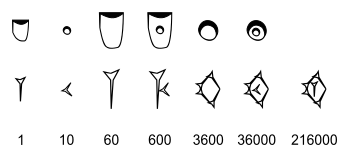

By 1928, experts had already created a list of the numbers used in proto-cuneiform. They did this by comparing them to the earliest cuneiform texts, which came right after proto-cuneiform. The number system, which was based on the number 60 (called sexagesimal), was largely understood by the 1970s. Some small details are still being debated today.

What Kinds of Signs Did They Use?

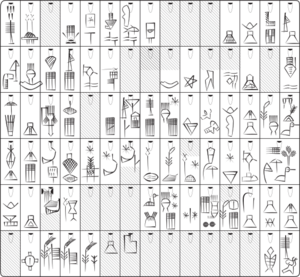

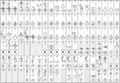

Today, we know about 2,000 different proto-cuneiform signs. About 350 of these are numbers. Around 1,100 are individual "ideographic" signs, meaning they represent an idea or object. The other 600 are complex signs, made by combining individual signs.

Many signs were used only once or a few times. But about 104 signs were used more than 100 times. Some common signs represented things like barley and a type of wheat called emmer.

Numbers in Proto-Cuneiform

The number system in proto-cuneiform, like later cuneiform, was based on the number 60. This is called a sexagesimal system. Imagine counting in groups of 60 instead of groups of 10!

People used different measurement systems for different products. For example, one system might be used for grain rations, another for barley, and yet another for emmer wheat. There were 13 different number systems in total!

What Kinds of Texts Were Written?

Most proto-cuneiform texts are "administrative accounts," which are like economic records. These records list various items, including people, animals, and grain. It can be a bit confusing because there were often several ways to write the same thing. For example, people could be listed by their gender and age (adult, child, baby), or just by age groups (like 0-1 year olds, 3-10 year olds, etc.).

Another large group of texts are called "lexical lists." These lists appeared early on and became very popular. They are lists of items grouped by category, such as metals, cities, or tools. These types of lists continued to be used for a very long time, even into later periods.

Gallery

See also

- Proto-Elamite

- Blau Monuments

- Liste der archaischen Keilschriftzeichen

- Kushim (Uruk period)

- Babylonian cuneiform numerals

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |