Codex Boturini facts for kids

The Codex Boturini, also known as the Tale of the Mexica Migration, is an ancient Aztec codex (an old book or manuscript). It tells the amazing story of how the Azteca people, who later became known as the Mexica, journeyed from their legendary homeland called Aztlán. We don't know the exact year it was made. It was likely created just before or soon after the Spanish arrived in the Aztec Empire. This important codex has influenced other Aztec books. Today, the Codex Boturini is a key symbol of Mexica history and their great journey. You can even see it carved into a stone wall at the entrance of the National Museum of Anthropology and History in Mexico City. The original codex is kept safe at this museum.

Contents

What is the Codex Boturini?

This special ancient book is called either the Codex Boturini or the Tira de la Peregrinación de los Mexica. The first name comes from a person named Lorenzo Boturini Benaduci. He was an Italian scholar from the 1700s who collected many Aztec manuscripts.

How Was the Codex Made?

The Codex Boturini is a very long sheet of paper. It is about 549 centimeters (about 18 feet) long and 19.8 centimeters (about 7.8 inches) high. This sheet is made from amate, a type of paper from tree bark. It is folded up like an accordion into 21.5 sections. Each section is about 25.4 centimeters (10 inches) wide.

The artist who made the Boturini Codex was called a tlacuilo. This artist knew the Aztec writing system very well. The pictures in the codex all look very similar. This suggests that only one person drew the entire book. Some alphabet writing in the Nahuatl language was added later.

The codex looks like it was never fully finished. It was only painted with red ink. This red ink was used to connect the date symbols. Artists at that time used natural colors for their paintings. These colors were easy to find before and after the Spanish arrived. Red and black were very important colors for tlacuiloque (artists) in ancient times.

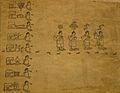

The red lines of ink connect the date symbols to the places the Mexica people arrived at. Some parts of the codex show where the artist erased things. This tells us that the tlacuilo first tried to connect dates and places in a different way. But then, the artist decided to use black ink footprints instead. These footprints show the Mexica moving from one place to the next.

The codex also has 24 notes written in Nahuatl. These notes are in a faded brown ink and were added after the codex was made. A scholar named Patrick Johansson Keraudren studied these notes. He found that they were mostly place names or short phrases from the 1500s.

Making the Paper and Drawings

The sheets of amate paper were glued together on the front side. Strong strips were added along the folds on the back. The glue was made from orchid roots and sap from the guanacaste tree. After gluing, the tlacuilo put a white layer called gesso on the paper. This made the surface smoother and filled the paper's tiny holes. This was only done on the front side.

Then, the tlacuilo drew the entire codex using a light black ink. After that, the artist connected the symbols and date blocks with a light red ink line. Once any corrections were made, the tlacuilo drew over the light black ink with a darker black ink. You can still see the lighter ink in some places. The red draft lines were never painted over. You can also see where the artist erased some parts. An art scholar named Angela Herren Rajagopalan thinks the artist worked on the whole codex at once, not just one page at a time.

The red ink used for the draft lines was probably a watered-down extract from cochineal insects or a clay-based color.

The History of the Codex

We don't know the exact date the Codex Boturini was created. However, it was likely made in the early 1500s in the Basin of Mexico. For a long time, people thought the codex was made before the Spanish arrived. But in the mid-1900s, scholars like Donald Robertson started to disagree. He pointed out that the date symbols were grouped and "edited." This suggested it was made after the Spanish conquest. Before the conquest, date symbols were usually in a continuous line.

Another historian, Pablo Escalante, also thought it was made after the conquest. He noted the lack of color and the simple drawings of people. These artistic choices suggest the codex was made during or right after the Spanish conquest. The materials and style of the codex are very similar to what early European explorers described about the first codices from the New World.

Early descriptions of the Boturini Codex said it was made of agave paper. But later studies found it was made of amate paper. Both types of paper were used before European paper factories were built.

The Codex Boturini became part of Lorenzo Boturini Benaduci's collection. He lived in New Spain (now Mexico) from 1736 to 1743. He started listing his collection while in prison in 1743. Later, more lists of his collection were made. The Boturini Codex was always listed as the first item. The codex stayed in Mexico until 1823.

Then, an English traveler and collector named William Bullock took the codex to London. It's not clear how he got it. He showed it in an exhibition about Mexico in 1824. After the exhibition, Bullock returned the codex to Mexico. We don't know the details of its return. The codex changed a lot during this time. Bullock added a label to the last page. It also seems that some of the final pages were lost between 1804 and 1824. At some point, gold paint was added to the edges of the codex.

Once back in Mexico, the Codex Boturini and other ancient items went to the new National Museum. This museum, now called the National Museum of Anthropology, still keeps and displays the codex. In 2015, a digital version of the codex was put online by the museum.

What Stories Does the Codex Tell?

The codex shows the events of the Mexica people's journey from Aztlán. It covers their history from the years 1168 to 1355 AD.

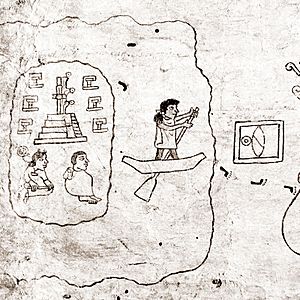

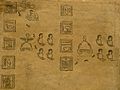

It starts with a priest leading Chimalma, an important ancestor of the Azteca, in a boat from Aztlán. When they reach the shore near Colhuacan, they build a special altar for their god, Huitzilopochtli. He was the one who told them to start this journey. There, they meet eight other tribes who want to join them. The Azteca agree. The nine tribes then set out. They are led by four "god-bearers": Chimalma, Apanecatl, Cuauhcoatl, and Tezcacoatl. Each of them carries a tlaquimilolli (a sacred bundle).

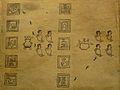

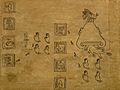

On pages 3 and 4, the Azteca become the Mexica. This happens when Huitzilopochtli chooses them to be his special people. He teaches them to offer blood to him. He also causes the Mexica to separate from the other eight tribes. This is shown on page 3 with a broken tree and another image of Huitzilopochtli. Next, five men eat together. Then, six men sit together, talking and crying. Above them, an Aztec man follows Huitzilopochtli's order to break away from the other tribes. This happens during a nighttime talk.

On page 4, the Mexica make their first human sacrifices to Huitzilopochtli. The people being sacrificed are shown wearing animal fur clothes. This tells us they are not Mexica. The person who separated from the other tribes performs these sacrifices. Huitzilopochtli appears again, this time as an eagle. He is above the victims. A Mexica man brings him a bow, an arrow, a bow drill, and a woven basket.

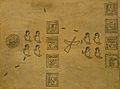

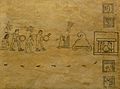

The Mexica arrive in the Basin of Mexico at Chapultepec on page 18. This page also shows the first New Fire ceremonies and the invention of the atlatl (a tool for throwing spears). After staying for 20 years and celebrating the New Fire, the Mexica move on. But they are attacked and defeated near Acocolco. The winning warriors bring the Mexica leader Huitzilihuitl and his daughter Chimalaxoch to Coxcox. Coxcox was the ruler of Colhuacan.

The Mexica then form an alliance with Colhuacan. They marry people from Colhuacan. This gives them a connection to the important Toltec ancestors. Coxcox asks the Mexica to fight the Xochimilco people. He tells them to bring back the ears of their defeated enemies as proof.

The codex ends here, just before the founding of Tenochtitlan (the great Aztec capital). Old records from New Spain explain that pages lost in the early 1800s told about the Mexica's wars around Chapultepec, which they fought for Coxcox.

The invention of pulque (an alcoholic drink) is shown on page 13.

-

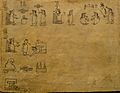

Folio 9. Beneath and below the glyph for Apaxco are the ghostly remains of two more date glyphs.

How is it Like Other Codices?

The Codex Boturini shares many similarities with another book called the Aubin Codex. The Aubin Codex tells almost the exact same journey. The main differences are in the dates for the first six places of the migration and at the very end of the Aubin Codex. The Aubin Codex focuses more on arrival dates, while the Boturini Codex emphasizes departure dates. Also, in the Aubin Codex, the victims of the first sacrifice to Huitzilopochtli do not look different from the Mexica people.

The Codex Mexicanus, which is a manuscript written over an earlier text, also looks a lot like the Boturini Codex. It also has footprints and red lines connecting date symbols. It also emphasizes departure dates, just like the Codex Boturini. However, the artists of the Codex Mexicanus only used black ink for the footprints.

See also

In Spanish: Tira de la Peregrinación para niños

In Spanish: Tira de la Peregrinación para niños

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |