Yaqui Wars facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Yaqui Wars |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Mexican Indian Wars and the American Indian Wars | |||||||

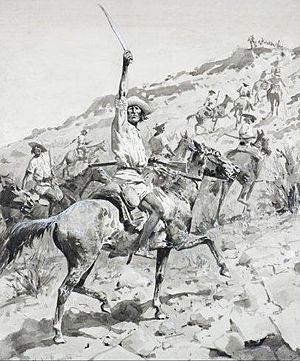

Uprising of the Yaqui Indians – Yaqui Warriors in Retreat, by Frederic Remington, 1896. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

(1533–1716) (1716–1821) (1821–1929) |

|

||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

|||||||

The Yaqui Wars were a series of conflicts that happened over a very long time. They involved the Yaqui people and the governments of New Spain (which later became Mexico). These wars started in 1533 and lasted until 1929. The Yaqui Wars were some of the last and longest Mexican Indian Wars. For nearly 400 years, Spanish and Mexican forces often fought against the Yaqui people in their territory. These fights led to many serious battles and difficult times.

Contents

A Long Fight for Land and Freedom

Early Conflicts: The 1700s

The main reason for these wars was similar to many other Mexican Indian Wars. In 1684, Spanish settlers found silver in the Yaqui River Valley in what is now Sonora, Mexico. After this discovery, more and more Spanish people began to settle on Yaqui land.

By 1740, the Yaqui people decided they had to fight back. There had been smaller conflicts before, even as far back as 1533. But in 1740, the Yaqui united with nearby tribes like the Mayo, Opata, and Pima. Together, they successfully pushed the Spanish settlers out of their lands by 1742.

Juan Banderas: A Leader for His People

During the Mexican War of Independence from Spain (1810–1821), the Yaqui people did not take sides. However, things changed when the Mexican state of Occidente passed a law in 1825. This law made the Yaqui people citizens and said they had to pay taxes. The Yaqui had never been taxed before, so they decided to fight.

The first battles took place at Rahum. A Catholic priest named Pedro Leyva encouraged the movement. The Yaqui people chose Juan Banderas as their leader. Juan Banderas was a respected Yaqui leader. In 1825, he had visions that inspired him to unite the Yaqui and other tribes. These included the Opata, Lower Pima, and Mayo people. He used the symbol of the Virgin of Guadalupe to bring them together.

Banderas successfully challenged Mexican rule in Sonora and Sinaloa from 1825 to 1832. The war was so intense that the capital of Occidente had to be moved. In 1827, Banderas' forces were defeated near Hermosillo. This happened partly because the Yaqui mainly used bows and arrows, while the Mexicans had guns. After this defeat, Banderas made peace with Occidente. He was pardoned and recognized as a captain-general of the Yaqui, even receiving a salary.

However, in 1828, the government ended the captain-general position. Occidente again said it had the right to tax the Yaqui. They also planned to divide Yaqui lands. So, in 1832, Banderas started the war again. He worked with Dolores Gutiérrez, a chief of the Opata people. Mexican forces captured Banderas and other Indian leaders after a battle at Soyopa, Sonora, in December 1832. In January 1833, Banderas, Gutiérrez, and ten others were executed. Juan Banderas remained a powerful symbol of Yaqui resistance.

Mid-19th Century: Continuing Resistance

After Juan Banderas's death, some Yaqui warriors kept fighting. They hid in the Sierra Vakatetteve mountains. In 1834, Yaquis at Torim tried to remove Mexican settlers from their area. Mexican forces in this fight were led by a Yaqui named Juan Ignacio Juscamea. Juscamea worked with the Mexican government until 1840. He was then killed by anti-Mexican Yaquis in a fight at Horcasitas.

During the 1830s and 1840s, the Yaqui often helped Manuel María Gándara. He was a former governor of Sonora. Gándara was fighting against José de Urrea for control of Sonora. In 1838, Urrea captured the Yaqui's coastal salt deposits. He then put them under state control.

In 1857, Ignacio Pesqueira removed Gándara from power. The Yaqui, led by Mateo Marquin (also known as Jose Maria Barquin), were key allies of Gándara. They helped him try to regain control of Sonora. At first, most of the fighting was in the Guaymas River valley. But in 1858, Cócorit became a place of violence. The Mayos joined the Yaqui in fighting the Mexican government. They also destroyed Santa Cruz, Sonora.

In August 1860, about 1,000 to 1,200 Yaqui and Mayo fighters marched towards Guaymas. They burned Mexican settlements as they went. The people of Guaymas prepared their town for defense. They armed 350 men. Governor Pesqueira left Hermosillo with 60 horsemen and 80 infantry. He planned to get more troops at El Cachora. However, the Yaqui attacked him and his troops at Jacalitos. This small village was about 42 miles from Hermosillo.

The Mexican troops were not experienced and ran away. Pesqueira and General Angel Trias were left with only a few bodyguards to face 600 well-armed Yaqui. They eventually escaped and joined forces at El Cachora. After this defeat, Pesqueira invaded Mayo and Yaqui territory in 1862. He forced them to agree to peace terms. The peace was made at Torim, Sonora. The terms allowed the Yaqui leaders to be pardoned. But it also required a military post at Agua Caliente, Sonora. This was so the Mexicans could control the Yaqui's actions.

French Intervention and Its Aftermath

After the French defeated Pesqueira at Guaymas in 1865, the Yaqui joined the French. They fought against the Mexicans. Mateo Marquin openly supported the French. Refugio Tánori, an Opata leader, also allied with the French. These native allies took control of Alamos, Sonora. They drove Pesqueira from his base at Ures.

In 1868, the French left Mexico. Pesqueira then appointed Yaqui leaders who supported Mexico to manage the Yaqui towns. But in Bácum, the Yaqui killed this official. Pesqueira then put Garcia Morales in charge of a campaign against the Yaqui. In 1868, 600 Yaqui surrendered at Cócorit. The Mexicans held 400 Yaqui in a church. When they felt the Yaqui were not cooperating, they fired cannons at the church. This caused a fire that killed 120 men, women, and children. This terrible event became known as the Bacum massacre.

Such harsh attacks made many Yaqui people leave their homes. Some moved to other places, while others were sent away by the Mexicans or forced into labor.

Cajemé: A Strong Leader

In 1874, Pesqueira appointed Cajemé as the main leader for all Yaqui and Mayo towns. However, when Pesqueira's son was named as the next governor, it caused trouble. There was an attempt to violently choose a new governor. Pesqueira reacted by attacking Cajemé and his people. From Medano, Pesqueira attacked many Yaqui residents. He killed Yaqui people just for being there and stole from their farms.

In 1876, the Yaqui leader José Maria Leyba Peres, known as Cajemé, created a small independent area in Sonora. By then, only about 4,000 Yaqui had not been defeated. They tried to protect their land by building a strong fort called El Añil (The Indigo). El Añil was near the village of Vícam, in a thick forest by the Yaqui river. The fort had a wide moat and a large trench for water. It also had a wooden wall made of thick tree trunks. This wall protected the 4,000 Yaqui people inside.

Agustin Ortiz, whose brother was the governor, led an attack in 1882 to capture Cajemé. Cajemé was wounded in the Battle of Capetemaya, but Ortiz's forces were defeated. Fighting in the Mayo areas continued until 1884. The Mayo people then agreed to Mexican rule. But Cajemé continued to fight for independence.

In 1885, Loreto Molino, a former lieutenant of Cajemé, raided Cajemé's home. The house was burned, but Cajemé was away and survived. This raid, approved by the Mexican government, led to a full-scale war again. In March 1886, three large groups of Mexican soldiers, each about 1,200 strong, moved against the Yaquis. Every important Mexican town was fortified. The Mexican Federal Forces used powerful machine guns against the Yaqui.

In May 1886, the Mexican army began attacking the main Yaqui fort, El Añil. General Carrillo attacked El Añil first. General Ángel Martínez then brought 1,500 more soldiers. El Añil was captured on May 12, 1886. Only a few Yaqui soldiers escaped into the mountains. About 200 Yaqui died, and 2,000 people, mostly elderly, children, and sick, were captured. The Mexican forces lost 10 officers and 59 troops.

After the battle, the people in nearby villages were pardoned by the Mexican government. They had to give up their weapons and were given clothes and food. Most of the remaining Yaqui soldiers could no longer fight the Mexican military directly. They hid in the mountains, being hunted down. Cajemé sent a message to General Juan Hernández, saying: "We will all obey the government, if within 15 days all your forces at the Rio Yaqui go back to Guaymas and Hermosillo. If not, you can do what you think is best; I, with my nation, am ready to fight until the very end."

Nearly a year later, Cajemé was captured near Guaymas. He was paraded through many Yaqui villages to show he was caught. On April 23, 1887, Cajemé was executed. Juan Maldonado took his place and continued a guerrilla war in the Sierra del Bacatete mountains. Many Yaqui towns along the Rio Yaqui became empty. People fled to the mountains or to other states in Mexico.

Yaqui Uprising of 1896

In February 1896, a new event called the Yaqui Uprising began. A Mexican revolutionary named Lauro Aguirre planned to overthrow the government. Aguirre convinced some Yaqui and Pima natives to join him. On August 12, a group of at least seventy men attacked the customs house at Nogales, Sonora. A battle followed, leaving at least three people dead and many wounded.

During the fight, a group of American militia from Nogales, Arizona, helped the Mexican defenders. The Yaquis and others had to retreat. This ended the uprising and led to the United States Army tracking the rebels. Two companies of the 24th Infantry Regiment were sent to hunt the rebels. Mexican Army Colonel Emilio Kosterlitsky also pursued them. However, the rebels escaped, some to Arizona.

In 1897, a peace treaty was signed in Ortiz between the Yaquis and the Mexican government. But in 1899, more fighting began. This led to the bloody Mazocoba Massacre of 1900. Several hundred natives were killed. Some Yaquis at Mazocoba survived the fighting but chose to take their own lives rather than surrender. Many Yaqui people began moving north to the United States. They settled around Tucson and Phoenix, Arizona, and parts of Texas.

Later Years and the End of the Wars

Around this time, President Porfirio Díaz wanted to find a solution to the Yaqui wars. By 1903, the government decided to send both peaceful and rebellious Yaqui natives to the Yucatan and Oaxaca regions. From 1904 to 1909, the Mexican governor of Sonora, Rafael Izábal, led "organized manhunts." During these, about 8,000 to 15,000 Yaquis were captured and forced into labor.

Between 1900 and 1911, many Yaquis, possibly 15,000 to 60,000, died during these forced movements. When the Mexican Revolution began in 1910, Yaqui warriors joined different rebel armies. They also started returning to their traditional lands along the Rio Yaqui. In 1911, Díaz was exiled, and President Francisco Madero took office. He reportedly promised the Yaqui people help for their losses. But by 1920, when the main part of the war ended, these promises were not kept.

By 1916, Mexican generals like Álvaro Obregón began taking Yaqui land for their own properties during the revolution. This led to more fighting between the Yaqui and the military.

During this period, the United States Army fought its last battle of the American Indian Wars. In January 1918, a small group of about thirty Yaqui natives was stopped by Buffalo Soldiers of the 10th Cavalry. This happened just across the border, near Arivaca, Arizona. In the thirty-minute fight, the Yaqui commander was killed, and some others were captured.

The last major battle of the Yaqui Wars happened almost ten years later. It is called "The Yaqui Revolt of 1926–1928." The battle began in April 1927 at Cerro del Gallo (Hill of the Rooster). On April 28, 1927, the Los Angeles Times reported that Mexican Federal Troops had captured 415 Yaquis. This group included 26 men, 214 women, and 175 children.

The Mexican newspaper El Universal reported that the Yaqui had retreated into the mountains. So, the Mexican Federal Staff decided to launch a major attack against them. General Obregón and General Manzo led these operations. Another report from October 5, 1927, said that 12,000 "federales" (federal troops) would soon be in Sonora. They would have machine guns, airplanes, and even poison gas. On October 2, 1927, the Los Angeles Times reported that General Francisco R. Manzo expected the Yaqui chief, Luis Matius, to surrender soon.

After this, some smaller fights continued into 1929. But the violence mostly ended due to bombings from the Mexican Air Force. The Mexican Army also set up posts in all Yaqui settlements. These actions helped prevent future conflicts.

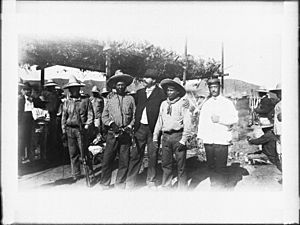

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Guerra del Yaqui para niños

In Spanish: Guerra del Yaqui para niños

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |