Francisco de Miranda facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Francisco de Miranda

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait by Martín Tovar y Tovar

|

|

| Supreme Chief of Venezuela | |

| In office 25 April 1812 – 26 June 1812 |

|

| Preceded by | Francisco Espejo |

| Succeeded by | Simón Bolívar (As President of the Second Republic of Venezuela) |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Sebastián Francisco de Miranda y Rodríguez de Espinoza

28 March 1750 Caracas, Venezuela |

| Died | 14 July 1816 (aged 66) Cádiz, Spain |

| Profession | Military |

| Nicknames | The Precursor The First Universal Venezuelan The Great Universal American |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Years of service | 1771–1812 |

| Rank | Generalissimo |

| Battles/wars | American Revolutionary War French Revolution Siege of Melilla (1774) Venezuelan War of Independence Battle of San Mateo |

Francisco de Miranda (born March 28, 1750 – died July 14, 1816) was a brave military leader and a revolutionary from Venezuela. He dreamed of freeing the Spanish American colonies from Spanish rule. Even though his own plans didn't fully succeed, he is seen as a very important person who came before Simón Bolívar. Bolívar later successfully helped many parts of South America become free.

Miranda was known as "The First Universal Venezuelan" and "The Great Universal American." He lived an exciting life during a time of big changes, influenced by the Age of Enlightenment. He took part in three major historical events: the American Revolutionary War, the French Revolution, and the Spanish American wars of independence. He wrote down all his experiences in a journal that filled 63 books! He had a big vision to free and unite all of Spanish America. Sadly, his military efforts for an independent Spanish America ended in 1812. He was captured and died in a Spanish prison four years later.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Miranda was born in Caracas, Venezuela Province, which was a Spanish colony at the time. His father, Sebastián de Miranda Ravelo, was a successful merchant from the Canary Islands. His mother, Francisca Antonia Rodríguez de Espinoza, was from a wealthy Venezuelan family.

Miranda grew up with a good education and went to the best private schools. His father wanted to improve the family's standing. He made sure his children received a college education. Miranda first learned from Jesuit teachers. Then he went to the Academy of Santa Rosa.

In 1762, Miranda started studying at the Royal and Pontifical University of Caracas. He learned Latin, grammar, and religion. He continued his studies, learning about history, geography, and arithmetic. In 1767, he earned his degree in Humanities.

Family Challenges

Miranda's family faced some difficulties because his father was from the Canary Islands. In 1764, his father became a captain in the local militia. This new position bothered some of the wealthy families in Caracas. They tried to cause problems for his father.

His father worked hard to prove his family's good name. He showed that his family had no African, Jewish, or Muslim ancestors. This was important to be accepted in society. In 1770, the King of Spain, Charles III, officially confirmed his father's title and standing. This victory, however, created lasting disagreements with the powerful families.

Adventures in Spain

After his father's legal victory, Miranda decided to start a new life in Spain. He left Caracas in January 1771 and arrived in Cádiz, Spain, in March. He then traveled to Madrid.

In Madrid, Miranda loved the libraries, buildings, and art. He continued his education, focusing on modern languages. He wanted to travel all over Europe. He also studied mathematics, history, and political science. He hoped to become a military officer for the Spanish King.

Miranda also started building his own library. He collected many books, old writings, and letters as he traveled. In 1773, his father sent him money to help him become a captain in the Princess's Regiment.

First Military Experiences

As a captain, Miranda traveled in North Africa and southern Spain. In December 1774, Spain went to war with Morocco. Miranda experienced his first battle during the Siege of Melilla. The Spanish forces successfully fought off the Moroccan sultan.

Even though Miranda was successful in the military, he faced some complaints. These included spending too much time reading and issues with money. He was transferred back to Cádiz.

Missions in America

Spain joined the American Revolutionary War to gain more land in America. In 1779, Spanish forces began to help their American allies. Miranda was sent to Havana, Cuba, in 1780.

Miranda took part in the Siege of Pensacola in 1781. He earned the temporary rank of lieutenant colonel. He also helped the French during the Battle of the Chesapeake. He helped them get money and supplies for the battle.

In the Caribbean

In 1781, Miranda went to Jamaica on a secret mission. He helped release 900 prisoners of war and got ships for the Spanish Navy. He also gathered information while he was there.

Miranda was later accused of being a spy and a smuggler. He was ordered to be sent back to Spain. However, his commander, General Cagigal, supported him.

Miranda also helped capture the Bahamas. He brought news of this victory to General Gálvez. This experience with Spanish officials made Miranda think more about independence for Spain's American colonies.

Escaping to the United States

The Spanish authorities wanted to arrest Miranda and send him to Spain. But Miranda found out about the plan. With help from his friends, he escaped on a ship to the United States. He arrived in New Bern, North Carolina in July 1783.

In the United States, Miranda studied the country's military defenses. He met many important people. He became friends with George Washington in Philadelphia. He also met Henry Knox, Thomas Paine, Alexander Hamilton, Samuel Adams, and Thomas Jefferson. He visited famous places like the Library of Newport and Princeton College.

Travels in Europe

Miranda left the United States in December 1784 and arrived in England in February 1785. The Spanish government watched him closely. They suspected him of planning against Spain.

Journey Through Europe

Miranda traveled a lot in Europe. He visited Prussia to see military exercises. He also went to Sweden and Norway. In Sweden, he met King Gustav III. He even visited Gunnebo House, a country home.

He then traveled through many other countries, including Belgium, Germany, Austria, Hungary, Poland, Greece, and Italy. He spent over a year in Italy.

Miranda visited the court of Catherine the Great in Russia. She was very kind to him and protected him from those who wanted to arrest him. She gave him a Russian passport. He also met the King of Poland, Stanisław II August. In Hungary, he stayed at the palace of Prince Nicholas Esterházy.

In 1790, Miranda used a disagreement between Spain and Britain to share his ideas about independence for Spanish territories in America with British leaders.

Miranda and the French Revolution

Starting in 1791, Miranda played an active role in the French Revolution. He became a general in the French army. He fought in the 1792 campaign of Valmy.

Miranda's army tried to capture Maastricht in February 1793 but failed. He was arrested and accused of plotting against the French Republic. He defended himself very well in court and was found innocent.

However, he was arrested again in July 1793 during a very dangerous time called the Reign of Terror. He stayed in prison even after the leader of the Terror, Robespierre, was removed from power. He was finally released in January 1795.

Miranda realized that the Revolution had gone wrong. He left France for England in January 1798.

Expeditions to South America

In 1804, Miranda presented a plan to the British to free Venezuela from Spanish rule. Britain was at war with Spain at the time. When the British decided to focus on other areas, Miranda traveled to New York in 1805. He began to organize his own expedition to free Venezuela.

First Attempt to Free Venezuela

Miranda met with President Thomas Jefferson and Secretary of State James Madison in Washington. They listened but did not get involved. In New York, Miranda secretly gathered money, weapons, and volunteers. He bought a ship and named it Leander. He set sail for Venezuela on February 2, 1806.

In Haiti, Miranda got two more ships. On March 12, he designed and raised the first Venezuelan flag on the Leander. On April 28, his attempt to land in Ocumare de la Costa failed. Two Spanish ships captured two of his vessels. Sixty of his men were imprisoned, and ten were executed.

Miranda escaped on the Leander and went to British islands like Grenada and Trinidad. He met with Admiral Alexander Cochrane. Since Spain was at war with Britain, Cochrane and the governor of Trinidad agreed to help Miranda with a second attempt.

On August 3, 1806, Miranda and his men landed in La Vela de Coro. They cleared the beach of Spanish forces and captured some cannons. Miranda then marched and captured Santa Ana de Coro. However, the people of the city did not support him.

A large Spanish force of almost 2,000 men arrived. Miranda realized his small force was too weak to hold Coro. On August 13, he ordered his men to sail away to Aruba.

After this failed attempt, Miranda spent the next year in Trinidad. He waited for more help that never came.

The First Republic of Venezuela

Venezuela became independent on April 19, 1810. A group called the Supreme Junta of Caracas took over from the Spanish rulers. The Junta sent a group to Great Britain to ask for help. This group included Simón Bolívar. They convinced Miranda to return to Venezuela.

In 1811, Miranda was warmly welcomed in La Guaira. In Caracas, he encouraged the government to declare full independence from Spain. He helped create a group called la Sociedad Patriotica, similar to political clubs in the French Revolution.

On July 5, 1811, Venezuela officially declared independence and formed a republic. The congress also chose Miranda's tricolor flag as the new nation's flag.

Challenges for the Republic

The new Republic faced many problems. Some areas of Venezuela remained loyal to Spain. Venezuela also lost its main market for cocoa, which caused money problems. This made many people, especially the poor, lose hope in the Republic.

Then, on March 26, 1812, a powerful earthquake hit the country. It caused many deaths and damaged buildings, mostly in areas that supported the Republic. Many people thought this was a sign from God. Royalist leaders said it was punishment for rebelling against the Spanish King.

Many people, including soldiers and priests, began to secretly work against the Republic or join the royalist side. Other provinces refused to send help to Caracas. Some provinces even switched sides.

Miranda's Leadership and Defeat

In these difficult times, Miranda was given special powers by the government. A Spanish captain named Domingo Monteverde gathered a large army. He advanced towards Valencia, leaving Miranda in charge of only a small part of Venezuela.

Bolívar lost control of San Felipe Castle in Puerto Cabello on June 30, 1812. Miranda saw that the republican cause was lost. He began talks with the royalists. They signed a peace agreement on July 25, 1812.

Miranda's Arrest

Bolívar and other revolutionary officers believed Miranda's actions were a betrayal. They arrested Miranda and handed him over to the Spanish Royal Army in La Guaira port. Bolívar then received a passport from the Spanish and left for Curaçao.

Miranda had planned to leave on a British ship before the royalists arrived. Bolívar later said he wanted to shoot Miranda for being a traitor. By handing Miranda over, Bolívar secured his own safe passage out of Venezuela.

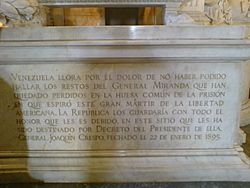

Final Years

Miranda never became free again. He died in a prison cell in Cádiz, Spain, on July 14, 1816, at the age of 66. He was buried in a mass grave, so his remains cannot be identified. An empty tomb is kept for him in the National Pantheon of Venezuela.

Miranda's Vision

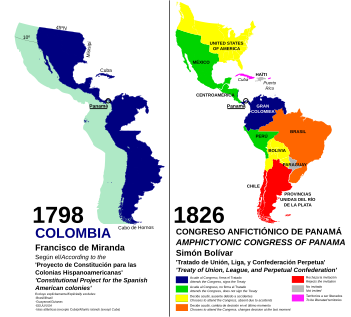

Miranda strongly believed in the independence of Spanish colonies in Latin America. He imagined a huge independent empire. It would include all the lands that had been ruled by Spain and Portugal. This empire would stretch from the Mississippi River to Cape Horn.

He thought this empire should be led by a hereditary emperor called the "Inca." This name honored the great Inca Empire. The empire would also have a two-part legislature. He called this grand empire Colombia, after the explorer Christopher Columbus.

Freemasonry

Like many important figures in American Independence, Miranda was a Freemason. In London, he started a lodge called "The Great American Reunion."

Personal Life

After fighting in the French Revolution, Miranda settled in London. He had two sons, Leandro and Francisco, with his housekeeper, Sarah Andrews. He later married Sarah.

Legacy and Honors

- A famous painting by Venezuelan artist Arturo Michelena, Miranda en la Carraca (1896), shows him in the Spanish prison where he died. This painting has become a symbol of Venezuelan history.

- In France, Miranda's name is carved on the Arc de Triomphe in Paris. His portrait is in the Palace of Versailles. There is also a statue of him in Paris.

- Many places in Venezuela are named after Miranda. These include the state of Miranda, a harbor called Puerto Miranda, a subway station, and a main avenue in Caracas. Several towns are also named "Miranda" or "Francisco de Miranda".

- The Caracas airbase and a Caracas park are named after him.

- The Order of Francisco de Miranda was created in 1939. It is an award for great achievements in science, national progress, and outstanding merit.

- In 2006, Venezuela's Flag Day was moved to August 3. This honors Miranda's landing at La Vela de Coro in 1806.

- One of the Bolivarian missions, Mission Miranda, is named after him.

- Miranda's life has been shown in Venezuelan films, including Francisco de Miranda (2006).

- There are statues of Miranda in many cities around the world, including Ankara, Bogotá, Caracas, London, Paris, and Philadelphia.

- The house where Miranda lived in London is now the Consulate of Venezuela in the United Kingdom. A special blue plaque marks it.

- Miranda's personal writings, called Colombeia, are kept in the National Archive of Venezuela. In 2007, UNESCO recognized this collection as part of the Memory of the World Register.

- In 2016, the Municipal Council of Caracas officially cleared Miranda of old charges like treason. He was also given the title of Chief Admiral after his death.

- The first Venezuelan Remote Sensing Satellite, launched in 2012, was named VRSS-1 after him.

Images for kids

-

Miranda's name transcribed beneath the Arc de Triomphe, column 4.

See also

In Spanish: Francisco de Miranda para niños

In Spanish: Francisco de Miranda para niños