Siege of Pensacola facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Siege of Pensacola |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Gulf Coast campaign | |||||||||

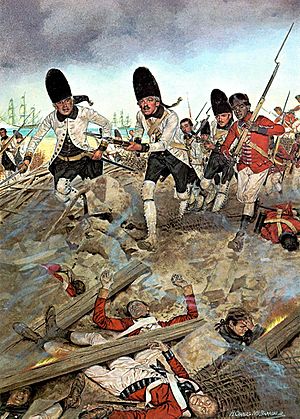

Spanish grenadiers and militia pour into Fort George. Oil on canvas, United States Army Center of Military History. |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 7,400 regulars & militia 10,000 sailors & marines 21 ships (Including 1,500 French sailors and 750 French soldiers) |

1,300 regulars, rangers, militia & natives 500 Indians |

||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 95 killed 202 wounded |

155 killed 105 wounded 1,113 captured 2 sloops captured |

||||||||

The Siege of Pensacola was a big battle in 1781. It was the final part of Spain taking control of British West Florida from the British. This happened during a larger fight called the Gulf Coast campaign. A siege is when an army surrounds a city or fort and tries to capture it by cutting off supplies and attacking.

Contents

Why Did the Siege of Pensacola Happen?

When Spain joined the war in 1779, Bernardo de Gálvez was the energetic governor of Spanish Louisiana. He quickly started military actions to take control of British West Florida. He began by attacking Fort Bute.

In September 1779, Gálvez took full control of the lower Mississippi River. He captured Fort Bute and then made the remaining British forces surrender after the Battle of Baton Rouge. He continued his success by capturing Mobile on March 14, 1780, after a short siege.

Gálvez then planned to attack Pensacola, which was the capital of West Florida. He wanted to use troops from Havana and use the recently captured Mobile as a starting point. However, British reinforcements arrived in Pensacola in April 1780, which delayed his plans. When his invasion fleet finally sailed in October, a hurricane scattered it a few days later. Gálvez spent almost a month gathering his fleet again in Havana.

How Were the British Defenses Set Up?

After fighting started with Spain in 1779, General John Campbell was worried about his defenses. He asked for more troops and started building new defenses. By early 1781, the Pensacola army included the 16th Regiment and a battalion from the 60th. It also had the 4th Battalion Royal Artillery.

These forces were joined by the Third Regiment of Waldeck and the Maryland Loyalist Battalion. The Pennsylvania Loyalists also joined. These were professional soldiers, not just local volunteers.

Some groups of Native Americans also helped the British. After Mobile fell in March 1780, many Native Americans came to Pensacola to help defend it. These allies included Choctaws and Creeks. The Creeks were the most numerous.

Just before the Spanish attack, only 800 Native American warriors remained in Pensacola. General Campbell had sent about 300 away, not knowing the attack was coming. During the siege, only about 500 were left. This was because the Muscogee Creeks tried to stay neutral, offering supplies to both sides. Most of the warriors still fighting for the British were Choctaw.

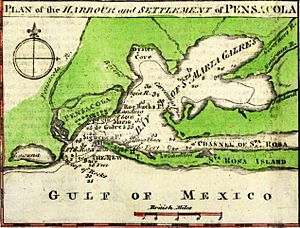

Gálvez had received detailed information about the defenses in 1779. He had sent an aide to Pensacola, supposedly to discuss runaway slaves. However, Campbell had made many changes since then. Pensacola's defenses in early 1781 included Fort George. This was an earth fort with a wooden fence on top, rebuilt by Campbell in 1780.

North of Fort George, Campbell had built the Prince of Wales Redoubt. To its northwest was the Queen's Redoubt, also built in 1780. Campbell also built a battery called Fort Barrancas Colorada near the entrance of the bay.

What Were the Spanish Forces Like?

Gálvez sailed with the Spanish fleet, which was led by Captain José Calvo de Irazabal. The fleet had about 1,300 men. These included a regiment from Mallorca and 319 men from Spain's Irish Hibernia Regiment, led by Arturo O'Neill de Tyrone. There were also militias of mixed-race and free Afro-Cubans. Gálvez had also ordered more troops from New Orleans and Mobile to help.

The Spanish forces sailed from Havana on February 13. They arrived outside Pensacola Bay on March 9. Gálvez landed some troops on Santa Rosa Island, which is a barrier island protecting the bay. O'Neill's Hibernians landed at the island battery. They found it undefended and brought in artillery. They used the artillery to drive away British ships hiding in the bay.

However, getting the Spanish ships into the bay was hard. It was similar to the problem they faced the year before at the capture of Mobile. Supplies were unloaded onto Santa Rosa Island to make some ships lighter. But Calvo, the fleet commander, refused to send more ships through the channel. This was after the lead ship, the 64-cannon San Ramon, got stuck. Also, some British guns seemed to be able to fire on the bay's entrance.

Gálvez used his power as Governor of Louisiana to take control of the ships from Louisiana. He boarded the Gálveztown and sailed it through the channel into the bay on March 18. The three other Louisiana ships followed him. The British artillery fire was not effective against them. After Gálvez sent Calvo a detailed description of the channel, all his captains insisted on crossing. They did so the next day. Calvo then claimed his job of delivering Gálvez's invasion force was done and sailed back to Havana in the San Ramon.

The Siege of Pensacola Begins

On March 24, the Spanish army and its militia moved to the main battle area. O'Neill acted as an aide and led the scout patrols. Once the bay was entered, O'Neill's scouts landed on the mainland. They stopped an attack by 400 mostly pro-British Choctaw Native Americans on the afternoon of March 28. The scouts soon joined the Spanish troops arriving from Mobile.

During the first weeks of April, O'Neill's Irish scouts explored the Pensacola forts. The farthest fort from the city was the Crescent. Next was the Sombrero, followed by Fort George. The Spanish troops set up camps and started preparing for the siege. Hundreds of engineers and workers brought supplies and weapons to the battlefield.

The engineers also dug trenches and built bunkers and small forts. They also built a covered road to protect the troops from constant fire. On April 12, Gálvez himself was wounded while looking at the British forts. Command of the battlefield was officially given to Colonel José de Ezpeleta, who was a personal friend of Gálvez.

A second attack by the Choctaws happened on April 19, stopping the siege preparations. That day, a large fleet was seen heading towards the bay. At first, everyone thought it was bringing British reinforcements. But the ships turned out to be the combined Spanish and French fleet from Havana. This fleet was commanded by José Solano y Bote and François-Aymar de Monteil. They had Spanish Field Marshal Juan Manuel de Cagigal on board.

Reports of a British fleet near Cape San Antonio had reached Havana. So, reinforcements had been sent to Gálvez. The Spanish ships carried 1,700 sailors and 1,600 soldiers. This brought the total Spanish force at Pensacola to a huge 8,000 men. Solano decided to stay and help Gálvez after the troops landed. The two men worked very closely together.

On April 22, 1781, the Spanish troops landed. They were led by Field Marshal D. Juan Manuel Cagigal and Squadron Chief of the Navy D. José Solano y Bote. By this day, General Bernardo de Gálvez had 7,800 experienced soldiers under his command. These included many different regiments from Spain and its colonies. There was also a small group of American patriots.

From the end of April to the beginning of May, the Spanish artillery positions became stronger. They dug trenches and tunnels closer and closer to the British defenses. This caused more damage to the English forts.

On April 24, a third Choctaw attack surprised the Spanish. No one was killed, but five Spanish soldiers were wounded. This included O’Neill's cousin, Sublieutenant Felipe O'Reilly. Two days later, soldiers from the Queen's Redoubt attacked Spanish positions. But O'Neill's scouts pushed them back.

On April 30, the Spanish cannons began firing. This signaled the start of the full attack on Pensacola. However, the Gulf was experiencing strong storms. A hurricane hit the Spanish ships on May 5 and 6. The Spanish fleet had to pull back, fearing the storms would wreck the ships on the shore. The army stayed to continue the siege, even though the trenches were flooded. Gálvez gave them a daily drink of brandy to keep their spirits up.

In early May, Gálvez was surprised when chiefs of the Tallapoosa Creeks visited him. They offered to supply the Spanish army with meat. Gálvez arranged to buy beef cattle from them. He also asked them to tell the British-allied Creeks and Choctaws to stop their attacks.

On May 8, a howitzer shell hit the gunpowder storage in Fort Crescent. It exploded, sending black smoke into the sky. Fifty-seven British troops were killed by the huge blast. Ezpeleta quickly led his light infantry in a charge to take the damaged fort. The Spanish moved howitzers and cannons into what was left of it. They then opened fire on the next two British forts. Pensacola's defenders fired back from Fort George, but the massive Spanish firepower soon overwhelmed them.

Two days later, General John Campbell realized his last line of defense could not survive the attack. He reluctantly surrendered Fort George and the Prince of Wales Redoubt. The British garrison raised a white flag over Fort George at 3 in the afternoon on May 10, 1781. More than 1,100 British and colonial troops were taken prisoner. There were 200 British casualties. The Spanish army lost 74 dead and 198 wounded.

Gálvez personally accepted the surrender from General John Campbell. This ended British control in West Florida after the surrender document was signed. The Spanish fleet left Pensacola for Havana on June 1. They went to prepare for attacks on the remaining British areas in the Caribbean. Gálvez appointed O'Neill as the Spanish Governor of West Florida. His Hibernia Regiment left with the fleet.

What Happened After the Siege?

The surrender terms included all of British West Florida, the British army there, and large amounts of war supplies. It also included one British warship. Gálvez moved the cannons and Fort Barrancas Coloradas closer to the bay's entrance. He also placed cannons on Santa Rosa Island. This was to stop British attempts to recapture Pensacola.

The Tallapoosa Muscogee Creek mission during the siege was likely connected to Alexander McGillivray. He was a mixed-race Creek trader. Even though he supported the British and was a British colonel, he had long opposed American colonists taking Creek land. McGillivray was raised as a Creek but was well-educated. Many Creeks saw him as their leader. He supplied the British in Pensacola and had organized the British Muskogee Creek groups who fought with the Choctaws.

He became the main Chief of the Upper Creeks in 1783. These Creeks lived on the Tallapoosa River. His support for Spain later led to the 1784 Treaty of Pensacola. In this treaty, Spain promised to respect Creek territory. In return, the Creeks promised to stop raiding their neighbors and disrupting trade. McGillivray personally negotiated the treaty and lived the rest of his life in Pensacola.

The Spanish fleet took the British prisoners to Havana. From there, they were sent to New York in a prisoner exchange. This made the Americans angry. However, such exchanges were normal. Gálvez arranged the exchange to free Spanish prisoners of war from British prison ships.

Gálvez and his army were welcomed as heroes when they arrived in Havana on May 30. King Charles III promoted Gálvez to lieutenant general. He was made governor of both West Florida and Louisiana. The king's praise said that because Gálvez alone forced his way into the Bay, he could put the words Yo Solo (meaning "me alone") on his coat of arms.

José Solano y Bote was later honored by King Charles III. He was given the title Marques del Socorro for helping Gálvez. A painting of Solano is now in the Museo Naval de Madrid. It shows him with Santa Rosa Bay in the background. A British flag captured at Pensacola is displayed at the Spanish Army Museum in Toledo.

See also

In Spanish: Batalla de Pensacola para niños

In Spanish: Batalla de Pensacola para niños