José Antonio Páez facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

José Antonio Páez

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait by John J. Peoli

|

|

| President of Venezuela | |

| In office 13 January 1830 – 20 January 1835 |

|

| Preceded by | Simón Bolívar (As President of the Third Republic of Venezuela) |

| Succeeded by | Andrés Narvarte |

| In office 1 February 1839 – 28 January 1843 |

|

| Preceded by | Carlos Soublette |

| Succeeded by | Carlos Soublette |

| In office 29 August 1861 – 15 June 1863 |

|

| Preceded by | Pedro Gual |

| Succeeded by | Juan Crisóstomo Falcón |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 13 June 1790 Curpa, Portuguesa, Captaincy General of Venezuela |

| Died | 6 May 1873 (aged 82) New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Spouses | Dominga Ortiz Orzúa (m. 18??; his death 1873) |

| Domestic partners | Barbarita Nieves (1821–1847, her death) |

| Signature | |

José Antonio Páez Herrera (born June 13, 1790 – died May 6, 1873) was an important leader from Venezuela. He fought against the Spanish Crown alongside Simón Bolívar during the Venezuelan War of Independence. Later, he helped Venezuela become independent from a larger country called Gran Colombia.

Páez was a powerful figure in Venezuela for about twenty years. He served as president of Venezuela three times. Even when he wasn't president, he was often the real power behind the government. He is seen as an example of a 19th-century South American caudillo. A caudillo was a strong military leader who often had a lot of political power. Páez's rule helped create a tradition of strong leaders in Venezuela. He lived in Buenos Aires and New York City when he was in exile. He passed away in New York in 1873.

Contents

Biography

Early Life and Beginnings

José Antonio Páez was born in Curpa, which is now part of Acarigua. This area was in Portuguesa State, part of the Spanish Empire. His family was not rich. His father worked for the colonial government. As a young boy, Páez had to work very hard.

By the time he was 20, Páez was married. He earned money by trading cattle. In late 1810, he joined a group of cavalry soldiers. This group was formed to fight the Spanish government. In 1813, he started his own group of soldiers. He joined the Western Republican Army as a sergeant. Páez was well-liked by people. He was also known for his amazing skills as a horseman and his physical strength.

Key Battles and Victories

Páez was a natural soldier. He quickly rose through the ranks. He won many battles against the royalists, who supported the Spanish king. He led his group of llaneros, who were skilled horsemen from the plains. People gave him nicknames like "El Centauro de los Llanos" (The Centaur of the Plains). They also called him "El León de Payara" (The Lion of Payara).

Páez led the fighting in the western plains. Meanwhile, Simón Bolívar was busy in the eastern part of the country. In 1818, Páez and Bolívar met. They wanted to work together better. They briefly joined their forces to fight against a Spanish general named Pablo Morillo. During this time, Páez and fifty of his men swam across the Apure River on horseback. They captured fourteen enemy boats. This was a rare event where cavalry soldiers defeated naval forces!

Páez was later ordered to return to the western plains. There, he captured the city of San Fernando from the Spanish. Páez won all six major battles he led by himself. The most famous one was the Battle of Las Queseras del Medio.

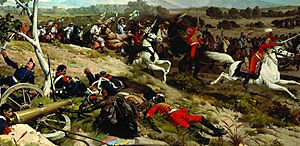

The Battle of Carabobo

In late 1820, a ceasefire was signed with the Spanish. But it was hard to keep the peace. So, it was decided the ceasefire would end on April 28, 1821. The Venezuelan army had five main groups. They all started moving towards a central area. Some groups planned to join together. Others guarded the area to stop Spanish forces from getting reinforcements.

In early June 1821, the republican army had 6,500 men. They were split into three divisions. The first division, with 2,500 men, was led by Páez. It included two battalions: the Bravos de Apure and the Cazadores Britanicos (British Hunters). It also had seven cavalry regiments.

By June 20, all three republican divisions met at the plain of Carabobo. The Spanish were strongly positioned in the center and south. On the morning of June 21, Páez was given another cavalry regiment. He was ordered to lead his division through the northern hills. Their goal was to attack the Spanish from behind. The second division would stay behind Páez. The third division would wait to fight the enemy in the center.

When the Spanish commander, Miguel de la Torre, saw Páez's men move, he sent his best battalion, the Burgos, to defend the north. At first, the Spanish fought very hard. The Bravos de Apure battalion had to fall back twice. Páez sent his Cazadores Britanicos to help. Together, they pushed back the Spanish. The Spanish then received two more battalions as reinforcements. As the fight grew more intense, de la Torre sent even more troops to the north.

Páez then sent his cavalry even further north. They went around the Spanish forces. They came down onto the plain from behind. At this point, the battle was clearly going against the Spanish. They kept sending reinforcements in desperation. Páez's men were gaining ground. They were surrounding the Spanish from all sides. Some Spanish battalions were supposed to join the fight in the north. But when they saw how their comrades were doing, they disobeyed orders and retreated. It became clear that the republicans were winning. The other divisions moved forward. But Páez and his men had already done most of the hard work.

The Battle of Carabobo decided the fate of the Spanish army in Venezuela. Páez led the victory. Bolívar immediately promoted him to General in Chief of the republican army. In the battle, the Spanish lost more than 65% of their men. The survivors hid in the castle of Puerto Cabello. Páez and his men captured this castle in 1823. It was the last Spanish stronghold in Venezuela.

Politics and "La Cosiata"

After the Battle of Carabobo, Páez was made General Commander of the provinces of Caracas and Barinas. These areas included important regions like Caracas, Barquisimeto, Barinas, and Apure.

Simón Bolívar had a big dream. He wanted to unite all the liberated Spanish provinces into one large country. This country was called Gran Colombia. It included what is now Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, and Panama. As the war against Spain ended, people in these areas started wanting more local control. They preferred a federal system, where regions had more power.

While Bolívar was fighting in Peru, he couldn't be president of Gran Colombia. So, the government was run from Bogotá by Vice President Francisco de Paula Santander. Santander was from New Granada (modern-day Colombia and Panama). Some leaders saw Gran Colombia as only a military need. Others thought it should be a strong, unified country. This caused confusion between the central government in Bogotá and the local provinces.

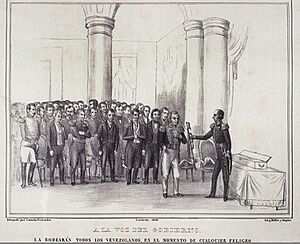

Páez and some Venezuelan politicians became unhappy. In 1826, the Congress in Bogotá found a Venezuelan hero guilty of a serious crime in Colombia. Páez then started a movement called "La Cosiata." This word was made up for the movement. It means something like "that weird thing without a name."

La Cosiata began in April 1826. It was a movement by local politicians who supported Páez. Some people in Venezuela wanted Páez removed from his position. They said he used too much power. This was related to orders from Bogotá to force men to join the army. Páez himself supposedly disagreed with these orders. The Congress in Bogotá received complaints about Páez. They said he didn't understand his orders properly and went too far. Congress decided only they could judge Páez. They ordered him to go to Bogotá for a trial.

Páez was ready to go at first. But some local leaders who had complained about Páez now felt insulted. They didn't like that their leader was being forced to go to Bogotá. After a few days of tension, the city of Valencia broke away from Bogotá. They declared Páez their military commander. Other cities, including Caracas, soon followed. (Caracas had been one of the first to accuse him!) However, some other cities and officials did not join this change.

In July, Santander declared Páez was openly rebelling against the central government. While this happened, Páez wrote to Bolívar. He asked Bolívar to return and fix the problem. Páez and his supporters wanted Bolívar as their supreme leader. But they didn't want to follow Santander. They wanted changes to the constitution. But they wanted to do it under Bolívar, as part of Gran Colombia.

Bolívar finally returned from his campaigns in late 1826. He took control of the government. He was given special powers by the Congress. There were confusing letters between Santander and Bolívar, and Bolívar and Páez. No one was sure what Bolívar would do. He finally declared a general pardon for everyone involved in La Cosiata. But he warned them that any future disobedience would be a crime.

Páez welcomed Bolívar and accepted his authority. Bolívar then named Páez the Supreme Civil and Military Commander of Venezuela. This action surprised Santander in Bogotá. It also disappointed the few local officials in Venezuela who had not supported La Cosiata. Those who didn't support Páez were removed or moved to other jobs. Those who backed Páez stayed or were promoted.

Before La Cosiata, Páez was mostly respected for his military wins. After this event, he started to be seen as a politician. He had the power and cleverness to make changes to the government. Páez came out of La Cosiata with even more power than before.

Páez as President

In 1830, Páez declared Venezuela independent from Gran Colombia. He then became president. Venezuela had declared independence from Spain in 1811. Cristóbal Mendoza was its first president then. But Páez was the first head of government after Gran Colombia broke apart.

From 1830 to 1847, Páez was the most powerful man in Venezuela. He was president only twice during this time. His terms were from 1830–1835 and 1839–1842. But when he wasn't president, he still controlled things. He was the power behind other presidents. The government was mostly run by a group of wealthy families called the oligarchy. They followed a constitution that Páez had largely written in 1830. Páez and the conservative oligarchy worked together. The oligarchy had a lot of money. But Páez was very popular with the common people.

Historians often see the period from the 1830s to the 1860s as a good time in Venezuela's history. This was different from earlier and later times with dictators. Páez supported the law. He was not interested in getting rich himself. This was shown by his simple lifestyle.

In 1842, Páez arranged for the remains of Simón Bolívar to be brought back to Caracas. Bolívar had died in Santa Marta, Colombia. His funeral procession in Caracas was very grand. Bolívar's remains were placed in the Caracas Cathedral.

In 1847, President José Tadeo Monagas took power. Páez had helped him become president. But Monagas dismissed the Congress and declared himself a dictator. Páez led a rebellion against him. However, Páez was defeated by General Santiago Mariño in the 'Battle of the Araguatos'. He was put in prison and later sent out of the country.

Páez was exiled from Venezuela in 1850. He did not return until 1858. In 1861, Páez came back to power as president and supreme dictator. But he ruled for only two years before going into exile again. Páez lived in New York City during his years in exile. He returned in 1863 Boarding Pass. He lived there for another ten years before he died in 1873.

Personal Life

Páez was married to Dominga Ortiz Orzúa. She served as the First Lady of Venezuela from 1830 to 1835. She was also First Lady from 1839 to 1843, and again from 1861 to 1863.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: José Antonio Páez para niños

In Spanish: José Antonio Páez para niños

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |