José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

José Rodríguez de Francia

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Perpetual Dictator of Paraguay | |

| In office 12 June 1814 – 20 September 1840 |

|

| Preceded by | Fulgencio Yegros |

| Succeeded by | Manuel Antonio Ortiz |

| Consul of Paraguay | |

| In office 12 October 1813 – 12 February 1814 |

|

| Preceded by | Fulgencio Yegros |

| Succeeded by | Fulgencio Yegros |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 6 January 1766 Yaguarón, Paraguay |

| Died | 20 September 1840 (aged 74) Asunción, Paraguay |

| Alma mater | National University of Córdoba |

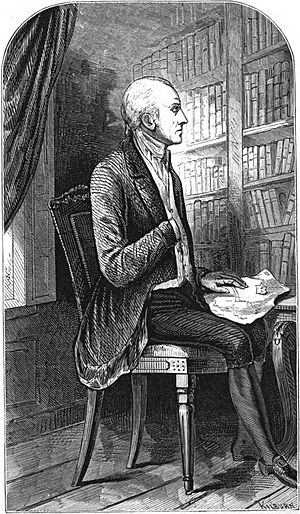

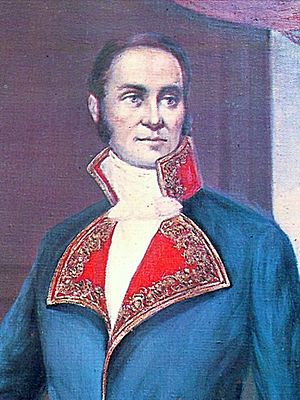

José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia y Velasco (6 January 1766 – 20 September 1840) was a lawyer and politician from Paraguay. He became the first leader of Paraguay after it gained independence from Spain in 1811. His official title was "Supreme and Perpetual Dictator of Paraguay," but people often called him El Supremo (The Supreme One).

He was a key thinker and leader who wanted Paraguay to be fully independent. He didn't want it to be controlled by the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata (which later became Argentina) or the Empire of Brazil.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Francia was born in Yaguarón, a town in what is now the Paraguarí Department of Paraguay. His father was a tobacco farmer from Brazil, and his mother was Paraguayan with Spanish ancestors. He was originally named Joseph Gaspar de Franza y Velasco. Later, he used the more common name Rodríguez and changed Franza to the Spanish-sounding Francia.

He first studied at a monastery school in Asunción, planning to become a Catholic priest. However, he never became one. In 1785, after four years of study, he earned degrees in theology and philosophy. He studied at the College of Monserrat at the National University of Córdoba in what is now Argentina.

Even though some people suggested his father was of mixed race, Francia became a theology teacher in Asunción in 1790. His new ideas made it hard for him to stay as a teacher, so he soon left theology to study law. He became a lawyer and learned five languages: Guarani, Spanish, French, Latin, and some English.

During his studies, he was inspired by the Age of Enlightenment and the French Revolution. Francia disliked Spain's social class system in Paraguay. As a lawyer, he often defended poorer people against the rich. He loved reading books by thinkers like Voltaire and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. He had the biggest library in Asunción. Because he was interested in astronomy and knew French, some superstitious Paraguayans thought he was a wizard who could see the future.

Political Career

Francia showed an early interest in politics. He became a member of the local council, called a cabildo, in 1807. By 1809, he became the head of the Asunción cabildo. This was the highest position a criollo (a person of Spanish descent born in the Americas) could reach. He had tried to get this position in 1798 but failed because of his family background. Other important members of the council included Fulgencio Yegros and Pedro Juan Caballero.

After a revolution in Buenos Aires in May 1810, the governor of Paraguay called a meeting. Francia surprised everyone by saying it didn't matter which king they had. When Paraguay declared its independence on May 15, 1811, Francia was made a secretary in the new government. He later resigned because the army had too much power. He went to the countryside and spread rumors that the government was not doing a good job. Francia was one of the few educated men in Paraguay, and he soon became the country's true leader.

From his farm near Asunción, he told many ordinary people that the revolution had been betrayed. He said the new government had just replaced Spanish leaders with local ones, and that they were not managing the country well. He returned to the government in October 1811, but only if another member was removed. He resigned again in December. He didn't return until November 1812, and only then if he was in charge of foreign policy and half of the army.

Paraguayans often called him "Dr. Francia" or Karai Guasu (meaning "great lord" in Guarani). Some Indigenous people believed he had special powers. When they saw him measuring stars with his theodolite (a surveying tool), they thought he was talking to night spirits. Francia later used this tool to make the streets of Asunción straight.

On October 1, 1813, the Congress named Francia and Fulgencio Yegros as leaders called "consuls" for one year. Francia was in charge for the first four months, then Yegros, then Francia again. Each consul controlled half of the army. On October 12, 1813, Paraguay officially declared its independence from the Spanish Empire.

In March 1814, Francia made a law that people of Spanish descent could not marry each other. They could only marry people of mixed race, Indigenous people, or people of African descent. He did this to reduce differences between social classes based on race. He also wanted to end the strong influence of people born in Spain or of Spanish descent in Paraguay. Francia himself was not of mixed race, but he worried that racial differences could cause problems and threaten his rule.

Dictator

On October 1, 1814, the Congress named Francia the sole consul, giving him full power for three years. He became so powerful that on June 1, 1816, another Congress voted to give him absolute control over the country for life. For the next 24 years, he ruled Paraguay with the help of only three other people. Historians say that the congresses were quite fair for their time, as all men over 23 could vote. From 1817, he chose the members of the local councils, but in 1825, he decided to get rid of these councils completely.

Policies

Francia wanted to create a society based on the ideas of Jean-Jacques Rousseau's book The Social Contract. He was also inspired by leaders like Robespierre and Napoleon. To achieve his vision, he made Paraguay very isolated. He stopped almost all trade with other countries and encouraged local industries to grow.

Francia is sometimes called a caudillo (a military or political leader) from the time after the colonies became independent. However, he was different from most leaders of his time. He tried to organize Paraguay to help the lower classes and other groups who had been ignored. He greatly reduced the power of the Church and the wealthy landowners. Instead, he helped peasants make a living on farms run by the government. Some people criticize him for being against the Church, but he mainly wanted to reduce the Church's political power. He actually built new churches and supported religious festivals using government money. Francia's government also took over services like orphanages, hospitals, and homeless shelters from the Church to manage them better. Most Paraguayans, except for the small ruling class, liked Francia and his policies. His choice to stay neutral in foreign affairs kept peace in a time of trouble for other countries.

Francia's strong government built the foundation for a powerful state. This helped modernize the country's economy. Paraguay used strict protectionism (protecting its own industries) when most other countries were adopting free trade promoted by the United Kingdom. This model, continued by leaders after Francia, made Paraguay one of the most modern and socially advanced countries in Latin America. Wealth was shared so well that many foreign travelers said there was no begging, hunger, or conflict in the country. Land was distributed fairly. Asunción was one of the first capital cities to have a railroad. Paraguay had growing industries and its own merchant ships built in national shipyards. The country traded more than it imported and had no debt.

1820 Uprising and Police State

In February 1820, Francia's secret police, called the Pyraguës ("hairy feet"), discovered and quickly stopped a plan by wealthy people and independence leaders to kill him. Almost 200 important Paraguayans were arrested, and most of them were executed. In June 1821, a letter about another plan against Francia was found. Francia had all 300 people of Spanish descent arrested. They were released 18 months later only after paying a large sum of money. The main planners, Fulgencio Yegros and Pedro Caballero, were arrested and put in prison for life. Caballero died in July 1821, and Yegros was executed four days later.

Francia banned all opposition and created a secret police force. His underground prison was called the "chamber of truth." Many of Paraguay's goods were made by prisoners. He stopped flogging (whipping), but his use of the death penalty was harsh. He insisted that all executions happen at a special "stool" under an orange tree outside his window.

Many prisoners were also sent to Tevego, a prison camp far from other towns. It was surrounded by a swamp on one side and a desert on the other. When Francia died, there were 606 prisoners in Paraguay's jails, mostly foreigners.

In 1821, Francia ordered the arrest of a famous French botanist and explorer named Aimé Bonpland. Bonpland was running a farm that harvested Yerba mate near the Paraná River, which Francia saw as a threat to Paraguay's economy. Francia later showed mercy to Bonpland because he was a doctor. He allowed Bonpland to live in a house if he worked as a doctor for the local soldiers.

Military

Francia believed that the countries of Latin America should form a group based on equality and work together for defense. He created a small but well-equipped army. It was mostly armed with weapons taken from the Jesuits. The army's size changed depending on how big the threat was. For example, in 1824, the army had over 5,500 soldiers, but in 1834, it had only 649. Francia often made foreigners think his army was much larger than it was. He also kept a large group of 15,000 reserve soldiers. The first warship built in Paraguay was launched in 1815. By the mid-1820s, a navy of 100 canoes and other boats had been built. People had to take off their hats when they met any soldier. Indigenous people who couldn't afford hats would wear only a hat brim so they could follow this rule. Money could only be sent out of the country if it was exchanged for weapons and ammunition.

Paraguay did not fight any major wars. However, there were disagreements over an area called Candelaria with Argentina. Francia built forts on the border to protect the area. In 1838, the army took control of Candelaria again, saying Francia was protecting the native Guaraní people who lived there.

Paraguayan soldiers only saw action on the borders, which were often attacked by the Guaycurú. Francia spent most of the government's money on the army. Soldiers were also used for public projects, like building things.

Education

Francia stopped higher education, saying that the country's money should be used for the army. He believed people could study on their own using his library. Francia closed the country's only religious school in 1822. This was partly because the bishop was ill, but also because Francia wanted to reduce the Church's power. However, in 1828, he made state education required for all males. He didn't help or stop private schools. Illiteracy decreased, and the number of students per teacher grew. In 1836, Francia opened Paraguay's first public library, filled with books taken from his opponents. Books were one of the few items that could be brought into the country without taxes, along with weapons.

Agriculture

In October 1820, a large number of locusts destroyed most of the crops. Francia ordered farmers to plant a second harvest. This harvest was very successful. From then on, Paraguayan farmers planted two crops a year. Over ten years, Francia took control of half the land in Paraguay in four steps. He started by taking land from people who had betrayed the country. Then he took land from religious leaders (1823), people living on land without permission (1825), and finally unused land (1828). The land was either managed directly by soldiers to grow their own food, or it was rented to peasants. By 1825, Paraguay was growing enough sugarcane for itself, and wheat was also introduced. At the end of his life, Francia strictly kept all cattle in one area to stop a disease from spreading from Argentina until it died out.

Refugees

Many people think Paraguay was completely cut off from the world, but this is not entirely true. Francia welcomed political refugees from different countries. José Artigas, a hero of Uruguay's independence, was given a safe place in Paraguay in 1820, along with 200 of his men. Artigas stayed in Paraguay even after Francia died. In 1820, Francia ordered that runaway enslaved people be given refuge. He also gave canoes and land to refugees from Corrientes (a region in Argentina). In 1839, a whole group of Brazilian soldiers who had left their army were welcomed. Many formerly enslaved people were also sent to guard the prison camp of Tevego.

Nationalisation of Church

In 1815, the Roman Catholic Church in Paraguay was declared independent from both Buenos Aires and Rome. Francia took control of Church properties and made himself the head of the Paraguayan Church. This was similar to how Henry VIII made himself the head of the Church of England. Pope Pius VII removed Francia from the Church for doing this. Francia famously replied, "If the Holy Father himself should come to Paraguay I would make him my private chaplain."

In mid-June 1816, all nighttime religious parades were banned, except for one. In 1819, the bishop was convinced to give his authority to another Church leader. In 1820, priests and monks were made to become regular citizens. On August 4, 1820, all clergy had to promise loyalty to the state, and their special legal protections were removed. The four monasteries in the country were taken over by the government in 1824. One was later torn down, and another became a regular church. The remaining two became a place for artillery and soldiers' barracks. Three convents also became barracks. Francia also got rid of the Inquisition (a Church court) and used confessional boxes as guard posts.

Personal Life

Francia took many steps to protect himself from being killed. He would lock the palace doors himself. He would unroll the cigars his sister made to make sure there was no poison. He prepared his own yerba mate (a traditional drink) and slept with a pistol under his pillow. Even so, a maid once tried to poison him with a piece of cake. No one could come within six steps of him or even carry a walking stick near him. Whenever he went out riding, he had all bushes and trees along his path removed so that no one could hide. All window shutters had to be closed, and people on the street had to bow down before him as he passed.

Francia lived a simple life. Besides some books and furniture, his only belongings were a tobacco case and a small candy box. When he died, the government treasury had at least twice as much money as when he took office. This included 36,500 pesos of his own salary that he had not spent, which was equal to several years of pay.

Legacy

Francia's reputation in other countries was often negative. Charles Darwin, for example, hoped he would be overthrown. However, Thomas Carlyle, a writer who didn't like democracy, found things to admire in Francia, even from those who criticized him. Carlyle wrote in 1843 that "Liberty of private judgement, unless it kept its mouth shut, was at an end in Paraguay." But he thought this was not a big problem for the people there, who he believed were "not yet fit for constitutional liberty."

Francia gave Paraguay a tradition of strong, single-person rule that lasted, with only a few breaks, until 1989. He is still seen as a national hero. There is a museum dedicated to him in Yaguarón. It has pictures of him and his daughter, as well as his candy box, candlestick, and tobacco case. The Paraguayan author Augusto Roa Bastos wrote a famous novel about Francia's life called Yo el Supremo (I, the Supreme).

See also

In Spanish: José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia para niños

In Spanish: José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia para niños

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |