Germán Busch facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Germán Busch

|

|

|---|---|

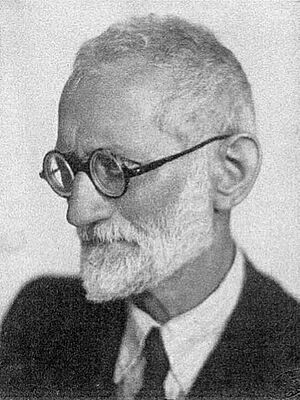

Official photograph with the Presidential Medal.

|

|

| 36th President of Bolivia | |

| In office 13 July 1937 – 23 August 1939 Junta: 13 July 1937 – 28 May 1938 |

|

| Vice President | Vacant (1937–1938; 1939) Enrique Baldivieso (1938–1939) |

| Preceded by | David Toro |

| Succeeded by | Carlos Quintanilla (provisional) |

| In office 17 May 1936 – 22 May 1936 Provisional |

|

| Preceded by | José Luis Tejada Sorzano |

| Succeeded by | David Toro |

| Supreme Leader of the Legion of Veterans | |

| In office 10 July 1937 – 23 August 1939 |

|

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Bernardino Bilbao Rioja |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Víctor Germán Busch Becerra

23 March 1903 San Javier, Ñuflo de Chávez, Santa Cruz, or El Carmen, Iténez, Beni, Bolivia |

| Died | 23 August 1939 (aged 35) La Paz, Bolivia |

| Cause of death | ... |

| Spouse |

Matilde Carmona

(m. 1928) |

| Children |

|

| Parents | Pablo Busch Raquel Becerra |

| Relatives | Alberto Natusch (nephew) |

| Education | Military College of the Army |

| Signature | |

| Nickname | Camba Busch |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1927–1937 |

| Rank | Lieutenant colonel |

| Unit | Campero Infantry Regiment Carabineros Corps Ingavi Cavalry Regiment |

| Commands | "Lanza" 6th Cavalry Regiment 4th Cavalry Brigade |

| Battles/wars |

|

| Awards | |

Víctor Germán Busch Becerra (born March 23, 1903 – died August 23, 1939) was a Bolivian military leader and politician. He served as the 36th president of Bolivia from 1937 to 1939. Before becoming president, he was the Chief of the General Staff, a top military position. He also led the Legion of Veterans, a group he started for soldiers who fought in the Chaco War.

Busch was born in either El Carmen de Iténez or San Javier. He grew up in Trinidad. He studied at the Military College of the Army and was a brave soldier in the Chaco War. Because of his actions, he became very important in the military. He helped remove presidents Daniel Salamanca in 1934 and José Luis Tejada Sorzano in 1936 from power. The second event helped his mentor, Colonel David Toro, become president of a military government. Busch was also part of this government. On July 13, 1937, Busch led a peaceful takeover that made Toro resign. This made Busch the new president of the government.

Busch was a war hero who believed in social changes happening at the time. He pushed for a new idea called military socialism, which Toro had started. He called for the 1938 National Convention. This meeting officially elected him president and created the 1938 Political Constitution. This new constitution was called a "Social Constitution." It said that the government had rights to the country's natural resources. It also mentioned that property should serve a social purpose and recognized the lands of native Bolivians. However, Busch was new to politics and used to strict military rules. This made it hard for him to lead different groups on the left side of politics. In 1939, he ended the legislature and declared himself a dictator. During this time, he issued many new laws. These included new rules for workers and schools, and a mining currency law. The mining law was very popular, but it angered the Rosca, which was a powerful group of mining owners.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Germán Busch was born on March 23, 1903. He was the fifth of six children. His father, Pablo Busch Wiesener, was a doctor from Germany. His mother, Raquel Becerra Villavicencio, was Bolivian with Italian family from Trinidad. His family traveled a lot, so his exact birthplace is debated by historians. Some say he was born in San Javier in the Santa Cruz Department. Others say he was born in El Carmen de Iténez in the Beni Department.

Historian Rolando Roda Busch, Germán's grand-nephew, says Busch was born in San Javier, Santa Cruz. He points to Busch's baptism certificate from August 25, 1903, in San Javier. He also mentions Pablo Busch's will, which lists his children's birthplaces.

Historian Robert Brockmann disagrees with the will. He says Pablo Busch wrote it when he was very ill. Brockmann points to Germán's mother, Raquel Becerra. She said Busch was born on a farm called "La Pampita" in El Carmen, Beni. This happened while the family was traveling on the Río Blanco to San Javier.

Even with the disagreement, everyone agrees Busch was born in 1903. Earlier histories said he was born in 1904. A few weeks after Busch was born, his father left the family and went back to Germany. Raquel Becerra moved with her children to her hometown of Trinidad. Busch spent most of his childhood there. He went to the 6 August National School. He was expelled at age 16 after a fight with the principal.

Military Career

His family decided Busch should attend the Military College of the Army in La Paz. His brother-in-law helped him get the needed good conduct certificates. To travel to La Paz, Busch won a swimming competition in Loma Suárez. He used the prize money to pay for a steamboat ticket for himself and three friends. They traveled by river to Todos Santos, then by mule through Cochabamba to La Paz. They arrived in December 1921. On January 16, 1922, at age 18, he joined the Military College.

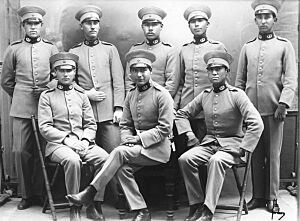

Military College of the Army

Busch was very good at physical training and exercise. However, he found the strict rules and focused study of military life challenging. A fellow cadet described Busch as "temperamental and violent." Busch graduated from the Military College on January 4, 1927. He became a second lieutenant and was sent to the Campero Infantry Regiment. He didn't like commanding heavy machine guns and often argued with other officers. So, six weeks later, he was moved to the Carabineros Corps in Copacabana. There, Busch met Captain David Toro. They became good friends. Toro asked for Busch to be transferred to the Ingavi Cavalry Regiment in Viacha, which Toro commanded. This allowed Toro to mentor Busch.

Marriage

The Military College was near an all-girls school called Liceo Venezuela. It was common for cadets and schoolgirls to form relationships. In 1926, Busch met Matilde Carmona Rodó there. She was from a once-rich mining family in Potosí. They already knew each other. Carmona knew Busch because he was popular among the schoolgirls. Busch knew Carmona because she published the student newspaper Ideal Femenino, which he liked. After he graduated and was sent to another town, they kept writing letters. Busch often visited her in La Paz when he could. In early 1928, Busch returned to La Paz to ask Carmona's family for her hand in marriage. He needed special military permission to marry. At that time, officers below the rank of captain were not allowed to marry. It was very unusual for a second lieutenant to marry. He needed a lot of convincing and special permission from General José C. Quirós, the Chief of the General Staff. Germán and Matilde married on February 18, 1928.

After his marriage, Busch was sent to the area around Cochabamba. His low salary as a second lieutenant, plus the birth of his first son, Juan Germán, in December 1928, and his second son, Orlando, just eleven months later, made life hard. The family struggled financially for some time and relied on the kindness of his friend Ángel Jordán.

1930 Coup d'état

In 1929, Busch and his family returned to La Paz. With Toro's recommendation, General Hans Kundt, the Chief of the General Staff, made Busch his personal assistant. However, Kundt and Busch's relationship soon became difficult. Busch felt his power was limited and he was falling behind in rank.

Busch's time in the General Staff was at the end of President Hernando Siles Reyes's term. Siles Reyes wanted to stay in power longer. He resigned in May 1930, asking his ministers to call a meeting to change the Constitution. This would let him run for a second term, which was not allowed. This plan backfired. By June 25, student protests had grown into an uprising at the Military College. Kundt, who was in charge of the military, did nothing to stop the crisis.

Busch heard from his wife that her brother and brother-in-law, among other officers, were imprisoned by rebelling soldiers. On the morning of June 25, without Kundt's permission, Busch went to the regiment's headquarters. He freed the arrested officers. At 4:00 AM the next day, Busch and eighteen soldiers took back the Military College. Busch then wanted to attack the Military Aviation School, but Toro told him to stop. On June 28, the military uprising succeeded in overthrowing the government. Busch went home, feeling that his actions were useless because of General Kundt's inaction. For supporting the old government, Busch was sent to the remote military post of Roboré.

San Ignacio de Zamucos Expeditions

In March 1931, Busch, now a lieutenant, was asked by President Daniel Salamanca to lead a group of thirty men. Their mission was to find the site of San Ignacio de Zamucos, an old Jesuit mission in the Chaco region. The government hoped finding this site would help prove Bolivia's claim to the Chaco Boreal area. The first trip began on March 25. A second trip was led by Lieutenant Colonel Ángel Ayoroa. In September, the government decided that finding old pottery and water systems was enough proof of the mission. Later, archaeologists found that there were never any ruins to discover there. Still, because of these trips, Busch received the Order of the Condor of the Andes on October 26.

Chaco War

Rising tensions between Bolivia and Paraguay over the Chaco Boreal led to war on September 9, 1932. Busch was happy about the news. He wrote in his journal, "I slept well. The voices spread that we are going to Boquerón, and I think that finally I am going to know what we asked so much for: War!"

On September 9, Busch's 6th Cavalry Regiment arrived in Muñoz. They helped defend Yucra on the road to Boquerón, fighting off attacks from Paraguayan regiments. However, attempts to break the Paraguayan siege of Boquerón failed. On the night of September 21-22, Lieutenants Germán Busch and Arturo Montes, with 15 soldiers, retreated. The battle ended with Bolivia losing Fort Boquerón. However, for entering Boquerón with help and breaking the siege to retreat, Busch was promoted to captain.

In November 1932, Busch led an attack behind Paraguayan lines. He attacked three or four Paraguayan trucks, killing thirty-seven Paraguayan soldiers and three officers. One of the officers was Lieutenant Hermán Velilla, whose family was important in Asunción. This made Busch very famous among the enemy. On March 11, 1933, his unit captured Fort Alihuatá and a lot of war supplies. For this, he was given command of the "Lanza" 6th Cavalry Regiment. That month, his regiment had three successful attacks, including capturing Fort Fernández.

Busch fought again at the Battle of Gondra. On July 15, his "Lanza" Regiment fought to protect the retreat of the 4th Division. This division was surrounded by Paraguayan forces. Busch's Bolivian soldiers worked to open a road to the north, towards Alihuatá, the only place the enemy had not reached. For three days, there was heavy fighting to keep the escape route open.

In late 1933, after Bolivia lost 9,000 soldiers, President Salamanca fired Kundt. He named Enrique Peñaranda as the new commander-in-chief of the armed forces. Peñaranda's staff included David Toro, Oscar Moscoso, and Germán Busch. Busch became Chief of Staff of the 1st Army Corps. Busch, who preferred action, first refused the job. But Toro convinced him, and Busch was promoted to major on December 30, 1933. Busch used his new position to push for more guerrilla attacks, planned retreats, and surprise attacks. He thought long defenses and mass attacks wasted soldiers and equipment.

1934 Coup d'état

The Chaco War was not going well for Bolivia. By November 1934, President Salamanca and Commander-in-Chief Enrique Peñaranda were in strong disagreement. On November 26, Salamanca fired Peñaranda. The next day, Salamanca went to the military headquarters in Villamontes to remove Peñaranda from his duties. On that day, military groups loyal to Peñaranda, including Colonel David Toro and Germán Busch, decided to resist. They planned to rebel against the president.

Soldiers were brought directly from the front lines. Under Busch's command, armed soldiers surrounded the house where President Salamanca was staying. The president was arrested, and the army leaders forced him to resign. This event was called the "Corralito de Villamontes." To keep up appearances of democracy, the military allowed Vice President José Luis Tejada Sorzano to become president and finish the war.

After the coup, in January 1935, Busch received the Grand Cross of Military Merit. In July, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel. In June, after the war ended, President Tejada Sorzano offered Busch a job in the Ministry of Defense. But the military leaders said no. On October 5, the first group of soldiers returning from the war arrived in La Paz. Busch was left as the temporary chief of the General Staff in La Paz. He formed a military group of three cavalry regiments. This gave Busch control over military actions in the capital city.

Political Rise

Bolivia's loss in the Chaco War in June 1935 caused a lot of trouble in the country. The old political system lost much of its support. New political groups, calling themselves "socialists," started to appear. Meanwhile, the military was having its own power struggles. Many blamed the old political parties for losing the war. The older military officers were also criticized for their bad tactics.

It didn't take long for the younger officers, who had quickly risen in rank during the war, to push out the old military leaders. These young officers supported the new left-wing movements in the country. They gathered around Lieutenant Colonel Germán Busch. On September 13, 1935, Busch formed the Legion of Veterans (LEC). This group quickly became a powerful political and military organization. Busch believed strongly in social change, but he wasn't a politician and couldn't create his own political ideas. So, Busch and the young officers decided that Colonel David Toro, who was more skilled in politics, should lead their movement.

1936 Coup d'état

Across Bolivia, labor unions caused problems with strikes. They demanded higher wages and benefits because of rising prices. President Tejada Sorzano was seen by many, including Busch, as one of the old politicians who had led them to war without proper equipment. So, when the government ordered the military to stop the strikes, the orders were ignored. Waldó Álvarez, the leader of the Federation of Workers of Labor (FOT), met with Busch and Toro. They promised the army would not act against the protesters. The biggest crisis came in May 1936 with a huge strike. On May 17, after buildings in La Paz were taken over, the military under Busch stepped in. They demanded Tejada Sorzano's resignation. A civil-military government was soon formed, and Busch was named temporary president. That same afternoon, Busch and Álvarez began talks, and all the unions' demands were met. Busch was temporary president until David Toro returned on May 20. Toro became president on May 22, and Busch joined the government as one of the leaders of the new group.

Busch in the Toro Government

Toro led a reform experiment called military socialism, which Busch supported. This government worked with labor and left-wing groups for over a year. However, Busch and the young officers grew impatient with the political actions of the left-wing groups. They especially disliked the constant arguments between the moderate socialists of Enrique Baldivieso's United Socialist Party (PSU) and the Socialist Republican Party (PRS) of Bautista Saavedra.

The PRS-PSU group quickly broke apart. Baldivieso's socialists didn't trust the "rightists" of the PRS. Saavedra, in turn, criticized the "communists" in the government. These complicated political moves frustrated Busch. On June 21, he took action within the government without telling President Toro. Saavedra was sent away to Chile. The alliance between the military and the civilian left-wing ended. From then on, the armed forces governed the country alone. Busch said that the left-wing parties had broken their agreements. He stated that the army would now rule without them, getting support from veterans and labor groups instead.

Busch easily carried out this change, which Toro had to accept. This showed how much influence Busch had over the government. As Busch gained more control over the military as Chief of the General Staff, Toro became more dependent on him. A clear sign of this was when Busch tried to resign from the General Staff on March 3, 1937. This was a vote of no confidence against Toro and shook his government. Toro rejected the resignation because military officers protested. This showed Toro clearly that they were loyal to Busch, not him.

1937 Coup d'état

Even though Toro passed popular laws like taking control of Standard Oil, his government soon lost the support of the native population and the army. Busch himself was unhappy with Toro's endless compromises, which seemed to lead nowhere. At a meeting in La Paz on July 10, the Legion of Veterans voted Busch Jefe Supremo (Supreme Leader) of their organization. This decision clearly rejected Toro as their leader.

The next day, Busch secretly met with Toro and General Enrique Peñaranda. He told the president that the army no longer trusted his government. Busch then asked Toro to write a resignation letter to the military groups. This was meant to show the public that the army was free to decide. Toro thought he would take command again when the military groups showed their trust in him. But Busch had hidden the fact that most military leaders were already against Toro. Then, Busch offered Peñaranda the presidency, which was refused as expected. This cleared the way for Busch to replace Toro.

Toro's resignation was never sent. On July 15, the military took him to an airport under false pretenses and sent him away to Chile. As a result of this takeover, Germán Busch became the new head of the government on July 13, 1937. He became president at age 34, making him one of Bolivia's youngest presidents.

President (1937–1939)

Even though Busch was a national hero, most people didn't know his political ideas. Both the left and the right thought he would go back to the old political ways. Busch didn't do much to clear this up, with his vague talks of "national renewal" and keeping "public order." He even had to deny claims that his takeover was paid for by Standard Oil. He said the new government had no plans to return the company's seized property.

Council of Ministers

The group of ministers Busch chose showed that his new government had trouble picking a clear direction. He seemed to favor careful spending by making Federico Gutiérrez Granier, a right-wing politician, the important Minister of Finance. Gutiérrez Granier had been Finance Minister under Tejada Sorzano, whom Busch himself had overthrown. Still, Busch let the minister reverse many of Toro's policies. This included closing government-supported food stores and ending various consumer subsidies.

Busch also allowed the more traditional senior military officers to regain power. In January 1938, Busch accused General Peñaranda of planning a coup. Instead of firing him, Busch challenged the general to a duel. The winner would become president. This accusation and challenge deeply offended Peñaranda. He angrily retired from his job as commander-in-chief of the army and left the government palace. Busch did little to stop Peñaranda's replacement, General Carlos Quintanilla, from removing young left-wing officers from their military positions. This was only stopped when left-wing lawmakers pressured him, fearing they would lose their allies in the military.

On the other hand, Busch's government adopted many of Toro's more radical ideas. He appointed Enrique Baldivieso, leader of the United Socialist Party, as Foreign Minister. He also made the moderate socialist Gabriel Gosálvez the Secretary-General of the government.

1938 National Convention

President Toro had planned a National Convention for 1938. After Toro resigned in March 1938, Busch and the new government called for an election for a group to rewrite the constitution of Bolivia. This meeting was a chance for new political groups after the war to challenge the old parties. The old parties tried to bring back the old ways.

Busch accepted support from the old parties and let his Finance Minister talk with them. But he also used Toro's idea of having unions in government. He allowed the Trade Union Confederation of Bolivian Workers (CSTB) and the Legion of Veterans to join the left-wing parties in the Socialist Single Front (FUS) electoral alliance. Busch supported this group in the upcoming elections. Facing this new movement led by Busch, the old parties (except the PRS, which joined the FUS) pulled out of the election. This allowed the "Generation of the Chaco" to win easily, giving them full control over the convention. On May 27, 1938, the convention elected Busch as the official President of the Republic, with Enrique Baldivieso as vice president. Both started their terms the next day, set to last until August 6, 1942.

On October 30, the convention created the 1938 Bolivian Constitution. This was a very important constitution because it focused on social issues. The new Constitution made workers' rights official and protected them. It allowed the government to be more involved in minimum wage, annual leave, and social security. It also brought social justice by recognizing the legal existence of Bolivia's native communities and providing for their education.

Constitutional Presidency (1938–1939)

Peace Treaty with Paraguay

On July 21, 1938, the Treaty of Peace, Friendship and Boundaries between Bolivia and Paraguay was signed in Buenos Aires. This officially ended the Chaco War. The treaty gave about 75% of the Chaco Boreal region to Paraguay. However, it included conditions set by Busch's government, mainly about Bolivia's access to the Paraguay River.

Creation of Pando Department

On September 24, Busch created the Pando Department as the ninth department of Bolivia. He named it after former President José Manuel Pando. This new department was meant to give the region more political importance and help it grow in population and economy. It also aimed to solve a problem for the people of Riberalta, who wanted to be the capital of a new department. However, during the convention, it was decided that Puerto Rico would be the capital instead of Riberalta. In 1945, the capital was moved to Cobija.

Left-wing Challenges

Busch spent most of his presidency working on the new political system. He couldn't pass many important reforms, even though he wanted to strengthen military socialism. The different left-wing groups, though gaining power, were always changing. The new assembly was the first since Tejada Sorzano was overthrown. Most members of the old parties had left, so there were few experienced politicians in Congress. Parties tried to form groups, but no strong national parties could emerge without clear leadership. Busch struggled to unite them.

Busch's efforts to bring parties together were weak. Renato Riverín, the former president of the national convention, and Gabriel Gosálvez, Busch's close advisor, tried to unite Baldivieso's moderate United Socialist Party with more radical groups. However, members of this government-backed Socialist Party worried that Busch wasn't fully committed. He was more used to the strict command of the army than the give-and-take of civilian politics.

The number of Busch's political allies became much smaller in March 1939. That month, Vice President Baldivieso stepped down from leading the moderate socialists, urging them to become more left-leaning. Soon after, on March 18, Gosálvez resigned as minister to focus on his diplomatic work in Rome as Ambassador to the Holy See. This removed him from Bolivian politics. Gosálvez's replacement, Vicente Leytón, refused to join Busch's attempt to form a national Socialist Party. While Busch announced he would support his own candidates, the failure of the united front was bad news for the left-wing in the upcoming May elections.

Old Parties Regroup

Busch's problems continued as the old parties regrouped after Bautista Saavedra's death on May 1, 1939. With Saavedra gone, the old parties stopped working with the moderate left. On March 22, 1939, the Liberal Party and both Republican parties put aside their differences. They formed the Concordance election alliance. They demanded an end to military involvement in politics and accepted support from the wealthy elite. They announced many candidates for the legislative elections.

Immigration Issue

Amidst the government's growing problems came the immigration issue. The scandal started in June 1938 when Busch's government suddenly announced open immigration to Bolivia. On June 9, Minister of Agriculture and Immigration Julio Salmón ended special rules for Jewish migration. This was likely to encourage Jews to settle in the Chaco before Paraguay did. Bolivia became the only country at the time to allow unlimited Jewish migration. This went against the strong pro-German feelings in the army.

The plan, supported by Moritz Hochschild, aimed to bring 10,000 European Jews to Bolivia within a year. With so many applications and desperate people, abuses happened. A scandal broke out when it was discovered that the consul general in Paris was charging Jewish people between ten and twenty thousand francs for a visa. Many people involved were fired. Still, Busch and his government faced accusations of serious moral wrongs and misconduct from the press.

Dictatorship Declared

Facing the immigration scandal, unhappy with his reforms, and with little support from the divided left, Busch grew tired of complex politics. On April 24, 1939, he declared himself a dictator. This ended the political system he had worked hard to create. Busch issued a statement to the nation. He said he had wanted to reorganize parties and have a free democracy and press. But he saw that "debauchery has been imposed" and "a subversive and demagogic fermentation has taken place." He declared, "From today on I begin an energetic and disciplined government." The assembly was suspended, elections were canceled, and the 1938 Constitution would now be enforced by his orders. In the following months, Busch issued important laws. These included taking control of various railways and industries, as well as the Central Bank.

General Labor Law

One of the most important and lasting changes from this time was the Código del Trabajo (Labor Code). This law was passed on May 24, 1939. It was called the Código Busch (Busch Code). It was based on earlier ideas by labor leader Waldó Álvarez. This law finally brought long-awaited social and labor reforms. It guaranteed job security, accident pay, paid time off, and the right for workers to negotiate together.

Mining Currency Law

On June 7, 1939, Busch issued one of his most important laws. This law ordered that 100% of all foreign money earned from tin exports had to be given to the Central Bank. The bank would then return the foreign money needed for the mining companies' verified expenses. A maximum of 5% could be used for paying shareholders. The rest would be given to them in Bolivian currency at a rate of 141 bolivianos per pound sterling. Companies with operating money abroad had to transfer it to the Central Bank within 120 days. Resisting this law was considered treason. While the law didn't aim to take over private mines, it was the first time the government could effectively get some of the earnings from Bolivia's powerful tin industry. It also showed the government's right to get involved in the country's economy.

This law was the most popular of Busch's time as president. Public excitement was as high as when Toro took control of Standard Oil. However, it made Busch the public enemy of the Rosca, Bolivia's powerful group of tin owners. They spoke out against the new law and got support from the conservative Concordance to oppose it. The Rosca's reaction was quick. Foreign Minister Eduardo Díez de Medina said that the big mine owners saw Busch's actions as a threat. They started a strong opposition against his policies. Busch received threats from all over the country. Busch knew this when he issued the law. He said, "I know that this step is extremely serious for my government and that many dangers lie in wait for me. But it does not matter, I am fighting for the Bolivian people and if I fall I will have fallen with a great flag: the economic freedom of Bolivia."

Legacy

Historian Robert Brockmann describes Busch as someone who made huge changes, whether he meant to or not. He says Busch is "part of the national mythology." While Herbert S. Klein says Busch's leadership lacked clear direction, he also states that Busch's government allowed new reform ideas to be heard for the first time. This marked "the end of national agreement and the beginning of strong class conflict in Bolivia." This eventually led to the Bolivian National Revolution in April 1952.

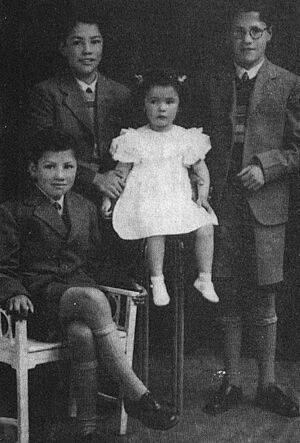

Colonel Alberto Natusch, who ruled Bolivia for 16 days in November 1979, was Busch's nephew. Germán Busch had four children: three sons, Germán, Orlando, and Waldo, and one daughter, Gloria. Gloria was born in 1940, a year after Busch died.

Links to Fascism

Because the Bolivian army had some German advisors and German-trained soldiers, Busch (who was partly German) was thought to have Nazi leanings. This idea grew stronger when, a week after becoming president in 1937, he asked for economic and oil advisors from Germany. On April 9, 1939, shortly before he declared himself dictator, Busch spoke with Ernst Wendler, the German minister in Bolivia. He asked for "moral and material support" to create "order and authority in the state through... the transition to a totalitarian state form." To do this, Busch asked for German advisors in almost every area of government. While Wendler was interested, the German government said no on April 22. They said they wanted to avoid "obvious measures, such as sending a staff of advisors."

While Busch liked some parts of Nazi ideas, he never agreed with their main beliefs about race and antisemitism. This is shown by his support for Jewish people moving from Europe. He also criticized the racist and regionalist Eastern Socialist Party, saying it was "an attack against national unity."

Busch has been described as someone who was against the old liberal governments, which he saw as corrupt. Busch and the time of military socialism in Bolivia happened before anti-fascism became strong and before National Socialism and Marxism clearly separated due to World War II. In Bolivia in the 1930s, the lines between different ideas of socialism (from national socialism to left socialism to moderate socialism) were not yet clearly defined.

Places and Monuments

Various places in Bolivia were named after him. This includes the Germán Busch Province in the Santa Cruz department. It was created on November 30, 1984. Puerto Busch, located in that province, is a river port on the international Paraguay River. For many decades, Puerto Busch was a forgotten port project. It became important again as a key trade and export area after Bolivia's loss to Chile in the Maritime Demand at the International Court at The Hague. The port offers Bolivia an alternative way to reach the Atlantic Ocean.

A monument to Germán Busch is in the Bolivian capital of La Paz. Other statues are in Pando, Beni, and Santa Cruz.

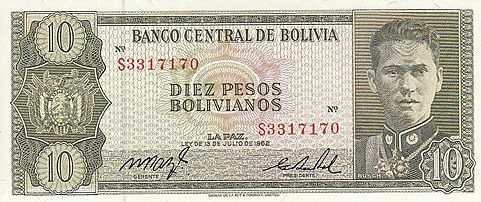

Currency and Postage

Bolivia changed its currency on January 1, 1963, to the peso boliviano. Busch's image was on the 10 peso note. However, due to inflation, the peso lost 95% of its value. So, the Bolivian boliviano replaced it on January 1, 1987. Busch does not appear on current Bolivian money.

See also

In Spanish: Germán Busch Becerra para niños

In Spanish: Germán Busch Becerra para niños

- Government Junta of Bolivia (1936–1938)

- Cabinet of Germán Busch

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |