Miguel Ángel Asturias facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Miguel Ángel Asturias

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | Miguel Ángel Asturias Rosales 19 October 1899 Guatemala City, Guatemala |

| Died | 9 June 1974 (aged 74) Madrid, Spain |

| Occupation | Novelist |

| Genre | Magic realism, dictator novel |

| Notable works | El Señor Presidente, Men of Maize |

| Notable awards | Lenin Peace Prize Nobel Prize in Literature 1967 |

Miguel Ángel Asturias Rosales (born October 19, 1899 – died June 9, 1974) was a writer, poet, and diplomat from Guatemala. He won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1967. His writings helped people understand the importance of native cultures, especially those in his home country of Guatemala.

Asturias was born and grew up in Guatemala. However, he lived much of his adult life in other countries. He first moved to Paris, France, in the 1920s. There, he studied ethnology, which is the study of different cultures. Some experts believe he was the first Latin American writer to show how studying cultures and languages could make literature better. In Paris, Asturias also joined the Surrealist art movement. He helped bring new, modern writing styles to Latin American literature. This made him an important writer before the "Latin American Boom" of the 1960s and 1970s, which was a time when many great Latin American novels became popular.

One of Asturias's most famous novels is El Señor Presidente. It describes life under a very strict ruler, known as a dictator. This book influenced other Latin American writers because it mixed real-life events with fantasy. Asturias openly spoke out against dictators. Because of this, he spent much of his later life living away from his home country, in places like South America and Europe. His book Hombres de maíz (Men of Maize) is often called his best work. It supports Mayan culture and traditions. Asturias used his deep knowledge of Mayan beliefs and his strong political ideas in his writing. His work often showed the hopes and dreams of the Guatemalan people.

After many years of living in exile and not being widely known, Asturias finally received a lot of recognition in the 1960s. In 1966, he won the Lenin Peace Prize from the Soviet Union. The next year, he was given the Nobel Prize for Literature. He was the second Latin American writer to win this award. Gabriela Mistral had won it in 1945. Asturias spent his last years in Madrid, Spain, where he passed away at age 74. He is buried in the Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris.

Biography

Early life and education

Miguel Ángel Asturias was born in Guatemala City on October 19, 1899. He was the first child of Ernesto Asturias Girón, who was a lawyer and judge, and María Rosales de Asturias, a schoolteacher. His brother, Marco Antonio, was born two years later. Asturias's parents were of Spanish background and came from respected families. His father's family had lived in Guatemala since the 1660s. His mother's family had a more mixed background, and her father was a colonel. In 1905, when Miguel was six, his family moved into his grandparents' house, where they had a more comfortable life.

Even though his family was well-off, Asturias's father did not like the government of Manuel Estrada Cabrera. Cabrera became a dictator in February 1898. Asturias later remembered, "My parents were quite bothered, though they were not put in prison or anything like that." In 1904, Asturias's father, as a judge, let some students go free after they were arrested for causing trouble. This led to a direct conflict with the dictator. His father lost his job, and in 1905, the family had to move to Salamá. This was a town in the Baja Verapaz region, where Miguel Ángel Asturias lived on his grandparents' farm. Here, Asturias first met Guatemala's native people. His nanny, Lola Reyes, was a young native woman who told him stories of their myths and legends. These stories greatly influenced his later writing.

In 1908, when Asturias was nine, his family moved back to the suburbs of Guatemala City. They opened a supply store where Asturias spent his teenage years. Asturias first went to Colegio del Padre Pedro and then Colegio del Padre Solís. He started writing as a student and wrote the first ideas for a story that would later become his novel El Señor Presidente.

In 1920, Asturias took part in the uprising against the dictator Manuel Estrada Cabrera. While studying at El Instituto Nacional de Varones (The National Institute for Boys), he actively helped to overthrow Cabrera's government. He and his classmates formed a group known as “La Generación del 20” (The Generation of 20).

In 1922, Asturias and other students started the Popular University. This was a community project where middle-class people taught free classes to those who were less fortunate. Asturias studied medicine for a year before changing to law at the Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala in Guatemala City. He earned his law degree in 1923 and won the Gálvez Prize for his paper on problems faced by native people. He also won the Premio Falla for being the best student in his department. At this university, he founded student groups like the Asociación de Estudiantes Universitarios (Association of University Students). He also took part in La Tribuna del Partido Unionista (Platform of the Unionist Party), which helped to end Estrada Cabrera's dictatorship. Asturias's involvement in these groups influenced many scenes in his novel El Señor Presidente. He also worked as a representative for a student association, traveling to El Salvador and Honduras.

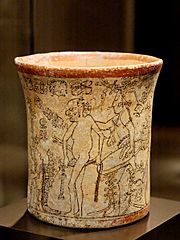

Asturias's university paper, "The Social Problem of the Indian," was published in 1923. After getting his law degree that same year, Asturias moved to Europe. He had planned to live in England and study economics, but he changed his mind. He soon moved to Paris, where he studied ethnology at the Sorbonne. He became a strong supporter of surrealism, influenced by the French poet André Breton. While in Paris, he was inspired by other writers and artists in Montparnasse. He began writing poetry and stories. During this time, Asturias became very interested in Mayan culture. In 1925, he started translating the Mayan sacred text, the Popol Vuh, into Spanish. This project took him 40 years. He also started a magazine in Paris called Tiempos Nuevos or New Times.

In 1930, Asturias published his first novel, Leyendas de Guatemala. Two years later, in Paris, he received the Sylla Monsegur Prize for the French translations of Leyendas de Guatemala. On July 14, 1933, he returned to Guatemala after ten years in Paris.

Exile and return

Asturias strongly supported the government of Jacobo Árbenz, who became president after Juan José Arévalo Bermejo. Asturias, who was an ambassador, was asked to help stop rebels from El Salvador. However, the rebels succeeded in invading Guatemala and overthrew Jacobo Árbenz's government in 1954. The U.S. government supported this overthrow because Árbenz's policies went against the interests of the United Fruit Company, which had a lot of power in Guatemala. When Árbenz's government fell, Asturias was forced to leave the country by Carlos Castillo Armas because he had supported Árbenz. He lost his Guatemalan citizenship and went to live in Buenos Aires and Chile for eight years. When the government in Argentina changed again, he had to find a new home and moved to Europe. While living in Genoa, Italy, his fame as an author grew with the release of his novel, Mulata de Tal (1963).

In 1966, Julio César Méndez Montenegro became president through a democratic election. Asturias was given his Guatemalan citizenship back. Montenegro appointed Asturias as ambassador to France, where he served until 1970. He then lived permanently in Paris. A year later, in 1967, English translations of Mulata de Tal were published in Boston.

Later in his life, Asturias helped start the Popular University of Guatemala. He spent his final years in Madrid, Spain, where he died in 1974. He is buried in the Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris.

Family life

Asturias married his first wife, Clemencia Amado (1915-1979), in 1939. They had two sons, Miguel and Rodrigo Ángel. They divorced in 1947. Asturias then met and married his second wife, Blanca Mora y Araujo (1904–2000), in 1950. Blanca was from Argentina. So, when Asturias was forced to leave Guatemala in 1954, he went to live in Buenos Aires, Argentina. He lived in his wife's home country for eight years. Asturias dedicated his novel Week-end en Guatemala, published in 1956, to his wife, Blanca. They stayed married until Asturias's death in 1974.

Asturias's son from his first marriage, Rodrigo Asturias, became a leader of a rebel group called the Unidad Revolucionaria Nacional Guatemalteca (URNG). He used the name Gaspar Ilom, which was the name of a native rebel in his father's novel, Men of Maize. The URNG was active in the 1980s during the Guatemalan Civil War and after the peace agreements in 1996.

Major works

Leyendas de Guatemala

Asturias's first published book, Leyendas de Guatemala (Legends of Guatemala; 1930), is a collection of nine stories. These stories explore Mayan myths from before the Spanish arrived and ideas about what it means to be Guatemalan. Asturias was very interested in old Mayan texts like Popul Vuh and Anales de los Xahil. His belief in popular myths and legends greatly influenced this work.

The book has been described as "beautiful stories of Guatemalan folk-lore" that get ideas from ancient Mayan and colonial times. For one critic, Leyendas de Guatemala was "the first important cultural contribution to Spanish American literature." Another expert said the stories were an early example of the magical realism style. Asturias used a mix of regular writing and poetic language to tell stories about birds and animals talking with people. His writing style in Leyendas de Guatemala has been called "history-dream-poem." In each legend, Asturias draws the reader into a world of beauty and mystery, where time and space feel different. Leyendas de Guatemala brought Asturias praise in both France and Guatemala. The famous French poet Paul Valéry said the book gave him "a tropical dream, which I experienced with singular delight."

El Señor Presidente

One of Asturias's most praised novels, El Señor Presidente, was finished in 1933 but not published until 1946 in Mexico. This early work showed Asturias's great talent as a writer. He wrote the novel while living in exile in Paris. El Señor Presidente is one of many novels that explore life under a Latin American dictator. Some even say it was the first true novel about dictatorship. The book has also been called a study of fear, because fear is everywhere in the story.

The play writer Hugo Carrillo turned El Señor Presidente into a play in 1974.

Men of Maize

Men of Maize (Hombres de maíz, 1949) is often seen as Asturias's greatest work. However, it is also one of his least understood novels. The title Hombres de maíz means "Men of Maize" and refers to the Maya Indians' belief that their bodies were made of corn. The novel has six parts, and each part shows the difference between old Indian customs and a new, modern society. Asturias's book explores the magical world of native communities, a topic he cared deeply about and knew a lot about. The novel uses traditional legends, but the story itself was created by Asturias.

The story is about a small native community (the "men of maize" or "people of corn") whose land is threatened by outsiders who want to use it for business. A native leader, Gaspar Ilom, leads the community's fight against these outsiders. He is killed, but he lives on as a "folk-hero." Despite his efforts, the people still lose their land. In the second half of the novel, the main character is a postman named Nicho. The story follows his search for his lost wife. During his journey, he leaves his job, which connects him to "white society," and turns into a coyote. This represents his guardian spirit. This change is another link to Mayan culture. The belief in nahualism, where a person can take the shape of their guardian animal, is key to understanding the hidden meanings in the novel. Through this story, Asturias shows how European influence changes native traditions in the Americas. By the end of the novel, the magical world of Indian legend is lost. But it ends with a hopeful idea, as the people become ants to carry the corn they have harvested.

Written like a myth, the novel is experimental and complex. For example, its "time works like a myth, where thousands of years can be squeezed into a single moment." The book's language is also made to sound like native languages. Because of its unusual style, it took some time for critics and the public to accept the novel.

The Banana Trilogy

Asturias wrote a long series of three novels about how native Indians were treated unfairly on banana plantations. This series includes three books: Viento fuerte (Strong Wind; 1950), El Papa Verde (The Green Pope; 1954), and Los ojos de los enterrados (The Eyes of the Interred; 1960). It is a made-up story about what happens when foreign companies control the banana industry in Central America. At first, only a few copies of these books were published in Guatemala. His criticism of foreign control over the banana industry and how Guatemalan natives were used earned him the Soviet Union's highest award, the Lenin Peace Prize. This made Asturias one of the few authors recognized in both the West and the Communist countries during the Cold War for his writing.

Mulata de tal

Asturias published his novel Mulata de tal in 1963 while he and his wife were living in Genoa. His novel received many good reviews. One review described it as "a carnival brought to life in a novel." It became an important novel in the 1960s. The story is about a fight between Catalina and Yumí to control Mulata (the moon spirit). Yumí and Catalina become skilled in magic and are criticized by the Church for their practices. The novel uses Mayan myths and Catholic traditions to create a unique story about beliefs.

One critic said that "the whole art of this novel depends on its language." Asturias used all the tools of the Spanish language to create a vivid picture, like a cartoon. His use of color is amazing and much more open than in his earlier novels. Asturias built the novel with this special use of color, new ideas, and his unique way of using the Spanish language. His novel also won the Silla Monsegur Prize for the best Spanish-American novel published in France.

Themes in his writing

Identity

The identity of people in Guatemala after colonial times is a mix of Mayan and European cultures. Asturias, who was a mestizo (someone of mixed European and native ancestry), suggested that Guatemala has a mixed national spirit. He believed it was Ladino (Spanish-speaking) in its language but Mayan in its myths. His goal to create a true Guatemalan identity is a main idea in his first published novel, Leyendas de Guatemala, and appears throughout his other works. When asked about his role as a Latin American writer, he said, "...I felt it was my calling and my duty to write about America, which would someday be of interest to the world." He also saw himself as a spokesperson for Guatemala, saying, "...Among the Indians there's a belief in the Gran Lengua (Big Tongue). The Gran Lengua is the spokesman for the tribe. And in a way that's what I've been: the spokesman for my tribe."

Politics

Throughout his writing career, Asturias was always involved in politics. He openly spoke against the Cabrera Dictatorship and worked as an ambassador in different Latin American countries. His political views are clear in many of his works. Some political ideas found in his books include: the Spanish colonization of Latin America and the decline of the Maya civilization; how political dictatorships affect society; and how the Guatemalan people were used by foreign-owned farming companies.

Asturias's collection of short stories, Leyendas de Guatemala, is based on Maya myths and legends. The author chose legends from the creation of the Maya people to the arrival of the Spanish conquerors hundreds of years later. Asturias introduces the Spanish colonizers in his story "Leyenda del tesoro del Lugar Florido" (Legend of the Treasure from the Flowering Place). In this story, a special ceremony is stopped by the unexpected arrival of "the white man." The tribe runs away in fear, and their treasure is left behind for the white man. This story shows the fall of the Maya civilization because of the Spanish conquerors.

El Señor Presidente does not directly say it is set in early 20th-century Guatemala. However, the novel's main character, the President, was inspired by the real president Manuel Estrada Cabrera, who ruled from 1898 to 1920. The President character rarely appears in the story, but Asturias uses other characters to show the terrible effects of living under a dictatorship. This book was an important addition to the "dictator novel" type of literature. Asturias could not publish the book in Guatemala for 13 years because of strict censorship laws under the Ubico government, a dictatorship that ruled Guatemala from 1931 to 1944.

After World War II, the United States kept increasing its business presence in Latin American countries. Companies like the United Fruit Company influenced Latin American politicians and took advantage of land, resources, and Guatemalan workers. The impact of American companies in Guatemala inspired Asturias to write "The Banana Trilogy." This series of three novels, published in 1950, 1954, and 1960, is about the unfair treatment of native farm workers and the strong control of the United Fruit Company in Guatemala.

Asturias was very concerned about the poverty and exclusion of the Maya people in Guatemala. He believed that Guatemala's economic and social growth depended on including native communities more, sharing wealth more equally, and lowering illiteracy rates. Asturias's choice to write about Guatemala's political problems in his novels brought international attention to them. He won the Lenin Peace Prize and the Nobel Prize for Literature because of the political criticisms in his books.

Writing style

Asturias was greatly inspired by the Maya culture of Central America. It is a major theme in many of his works and strongly influenced his writing style.

Mayan influence

Modern Guatemala was built on the foundations of Mayan culture. Before the Spanish arrived, this civilization was very advanced in politics, economy, and society. This rich Mayan culture had a clear influence on Asturias's writings. He believed in the sacredness of Mayan traditions and worked to bring their culture back to life by including native images and traditions in his novels. Asturias studied at the Sorbonne (University of Paris) with Georges Raynaud, an expert in the culture of the Quiché Maya. In 1926, he finished a translation of the Popol Vuh, the sacred book of the Mayas. Fascinated by the myths of Guatemala's native people, he wrote Leyendas de Guatemala (Legends of Guatemala). This fictional work retells some of the Mayan folk stories from his homeland.

Certain parts of native life were especially interesting to Asturias. Corn, or maize, is a very important part of Mayan culture. It is not only a main food but also plays a big role in the Mayan creation story found in the Popul Vuh. This story influenced Asturias's novel Hombres de maíz (Men of Maize). This mythological story introduces readers to the life, customs, and thoughts of a Maya Indian.

Asturias did not speak any Mayan language. He admitted that his ideas about the native mind were based on feelings and guesses. Because he took such liberties, there could be mistakes. However, some experts argue that his work is still valuable because, in this case, intuition was a better tool than scientific analysis. For example, Asturias used a poetic and experimental style in Men of Maize. This was seen as a more real way to show the native mind than traditional writing.

When asked about how he understood the Mayan mind, Asturias said, "I listened a lot, I imagined a little, and invented the rest." Despite his inventions, his ability to include his knowledge of Mayan culture in his novels makes his work feel real and convincing.

Surrealism and magical realism

Surrealism greatly influenced Asturias's works. This style explores the subconscious mind and allowed Asturias to mix fantasy and reality. Although Asturias's works were seen as coming before magical realism, he saw many similarities between the two styles. Asturias talked about magical realism in his own works, connecting it directly to surrealism. However, he did not use the term to describe his own writing. Instead, he used it for Mayan stories written before the Spanish conquest, like Popul Vuh or Los Anales de los Xahil. In an interview, Asturias explained how these stories fit his view of magical realism and relate to surrealism: "Between the 'real' and the 'magic' there is a third sort of reality. It is a melting of the visible and the tangible, the hallucination and the dream. It is similar to what the surrealists wanted and it is what we could call 'magic realism.'" Even though the two styles shared a lot, magical realism is often thought to have started in Latin America.

As mentioned, Maya culture was a key inspiration for Asturias. He saw a direct link between magical realism and the native way of thinking. He said, "...an Indian or a mestizo in a small village might describe how he saw an enormous stone turn into a person or a giant, or a cloud turn into a stone. That is not a tangible reality but one that involves an understanding of supernatural forces. That is why when I have to give it a literary label I call it 'magic realism.'" Similarly, experts say that surrealist thinking is not completely different from the native or mixed-race worldview. This worldview sees the line between reality and dreams as blurry, not clear. It is clear from Asturias's words that magical realism was a good way to show a native character's thoughts. The surrealist/magical realist style is shown in Asturias's works Mulata de tal and El señor Presidente.

Use of language

Asturias was one of the first Latin American writers to understand how powerful language could be in literature. He had a very deep and special way of using language to share his ideas. In his works, language is more than just a way to express things; it can be quite abstract. Language doesn't just give life to his work; the living language Asturias uses has a life of its own within his stories.

For example, in his novel "Leyendas de Guatemala," the writing has a rhythmic, musical style. In many of his works, he often used words that sound like what they mean (onomatopoeias), repetitions, and symbolism. These techniques are also common in old Mayan texts. His modern way of using the Mayan writing style later became his unique mark. Asturias combined the formal language found in the ancient Popul Vuh with colorful, lively words. This unique style has been called "tropical baroque" by experts studying his major works.

In Mulata de tal, Asturias mixes surrealism with native tradition in something called the "great language." In this Maya tradition, people give magical power to certain words and phrases, similar to a witch's chant or curse. In his stories, Asturias brings this power back to words and lets them speak for themselves: "Los toros toronegros, los toros torobravos, los toros torotumbos, los torostorostoros" ("the bulls bullsblack, the bulls bullsbrave, the bulls bullsshake, the bullsbullsbulls").

Asturias used a lot of Mayan words in his works. A list of these words can be found at the end of Hombres de maíz, Leyendas de Guatemala, El Señor Presidente, Viento Fuerte, and El Papa verde. This helps readers understand the rich mix of everyday Guatemalan and native words.

Legacy

After he passed away in 1974, his home country recognized his important contributions to Guatemalan literature. They created literary awards and scholarships in his name. One of these is the country's most important literary award, the Miguel Ángel Asturias National Prize in Literature. Also, Guatemala City's national theater, the Centro Cultural Miguel Ángel Asturias, is named after him.

Asturias is remembered as a person who strongly believed in recognizing native culture in Guatemala. For one critic, Asturias is one of the "ABC writers—Asturias, Borges, Carpentier" who "really started Latin American modernism." His experiments with writing style and language are seen by some experts as an early example of the magical realism style.

Critics compare his stories to those of Franz Kafka, James Joyce, and William Faulkner. This is because of the "stream-of-consciousness" style he used, where thoughts flow freely. His work has been translated into many languages, including English, French, German, Swedish, Italian, Portuguese, Russian, and many more.

Awards

Asturias received many honors and literary awards during his career. One of the most notable awards was the Nobel Prize for Literature, which he received in 1967 for Hombres de maiz. This award caused some discussion at the time because he was not very well known outside of Latin America. Some critics thought there were other more famous writers who deserved it. In 1966, Asturias was given the Lenin Peace Prize by the Soviet Union. He received this award for La trilogía bananera (The Banana Trilogy), in which he criticized the presence of powerful American companies like The United Fruit Company in Latin American countries. This recognition made Asturias one of the few authors recognized in both the Western and Communist parts of the world during the Cold War for his literary works.

Other awards for Asturias's work include: el Premio Galvez (1923); Chavez Prize (1923); and the Prix Sylla Monsegur (1931), for Leyendas de Guatemala; as well as the Prix du Meilleur Livre Étranger for El señor presidente (1952).

Works

- Novels

- El Señor Presidente. – Mexico City : Costa-Amic, 1946 (translated by Frances Partridge. New York: Macmillan, 1963)

- Hombres de maíz. – Buenos Aires : Losada, 1949 (Men of Maize / translated by Gerald Martin. – New York : Delacorte/Seymour Lawrence, 1975)

- Viento fuerte. – Buenos Aires : Ministerio de Educación Pública, 1950 (Strong Wind / translated by Gregory Rabassa. – New York : Delacorte, 1968; Cyclone / translated by Darwin Flakoll and Claribel Alegría. – London : Owen, 1967)

- El papa verde. – Buenos Aires : Losada, 1954 (The Green Pope / translated by Gregory Rabassa. – New York : Delacorte, 1971)

- Los ojos de los enterrados. – Buenos Aires : Losada, 1960 (The Eyes of the Interred / translated by Gregory Rabassa. – New York : Delacorte, 1973)

- El alhajadito. – Buenos Aires : Goyanarte, 1961 (The Bejeweled Boy / translated by Martin Shuttleworth. – Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1971)

- Mulata de tal. – Buenos Aires : Losada, 1963 (The Mulatta and Mr. Fly / translated by Gregory Rabassa. – London : Owen, 1963)

- Maladrón. – Buenos Aires, Losada, 1969

- Viernes de Dolores. – Buenos Aires : Losada, 1972

- Story Collections

- Rayito de estrella. – Paris : Imprimerie Française de l'Edition, 1925

- Leyendas de Guatemala. – Madrid : Oriente, 1930

- Week-end en Guatemala. – Buenos Aires : Losada, 1956

- El espejo de Lida Sal. – Mexico City : Siglo Veintiuno, 1967 (The Mirror of Lida Sal : Tales Based on Mayan Myths and Guatemalan Legends / translated by Gilbert Alter-Gilbert. – Pittsburgh : Latin American Literary Review, 1997)

- Tres de cuatro soles. – Madrid : Closas-Orcoyen, 1971

- Children's Book

- La Maquinita de hablar. – 1971 (The Talking Machine / translated by Beverly Koch. – Garden City, N.Y. : Doubleday, 1971)

- El Hombre que lo Tenía Todo Todo Todo. – 1973 (The Man that Had it All, All, All)

- Anthologies

- Torotumbo; La audiencia de los confines; Mensajes indios. – Barcelona : Plaza & Janés, 1967

- Antología de Miguel Ángel Asturias . – México, Costa-Amic, 1968

- Viajes, ensayos y fantasías / Compilación y prólogo Richard J. Callan . – Buenos Aires : Losada, 1981

- El hombre que lo tenía todo, todo, todo; La leyenda del Sombrerón; La leyenda del tesoro del Lugar Florido. – Barcelona : Bruguera, 1981

- El árbol de la cruz. – Nanterre : ALLCA XX/Université Paris X, Centre de Recherches Latino-Américanes, 1993

- Cuentos y leyendas. – Madrid, Allca XX, 2000 (Mario Roberto Morales Compilation)

- Poetry

- Rayito de estrella; fantomima. – Imprimerie Française de l'Edition, 1929

- Emulo Lipolidón: fantomima. – Guatemala City : Américana, 1935

- Sonetos. – Guatemala City : Américana, 1936

- Alclasán; fantomima. – Guatemala City : Américana, 1940

- Con el rehén en los dientes: Canto a Francia. – Guatemala City : Zadik, 1942

- Anoche, 10 de marzo de 1543. – Guatemala City : Talleres tipográficos de Cordón, 1943

- Poesía : Sien de alondra. – Buenos Aires : Argos, 1949

- Ejercicios poéticos en forma de sonetos sobre temas de Horacio. – Buenos Aires : Botella al Mar, 1951

- Alto es el Sur : Canto a la Argentina. – La Plata, Argentina : Talleres gráficos Moreno, 1952

- Bolívar : Canto al Libertador. – San Salvador : Ministerio de Cultura, 1955

- Nombre custodio e imagen pasajera. – La Habana, Talleres de Ocar, García, S.A., 1959

- Clarivigilia primaveral. – Buenos Aires : Losada, 1965.

- Sonetos de Italia. – Varese-Milán, Instituto Editoriale Cisalpino, 1965.

- Miguel Ángel Asturias, raíz y destino: Poesía inédita, 1917–1924. – Guatemala City : Artemis Edinter, 1999

- Theatre

- Soluna : Comedia prodigiosa en dos jornadas y un final. – Buenos Aires : Losange, 1955

- La audiencia de los confines. – Buenos Aires : Ariadna, 1957

- Teatro : Chantaje, Dique seco, Soluna, La audiencia de los confines. – Buenos Aires : Losada, 1964

- El Rey de la Altaneria. – 1968

- Librettos

- Emulo Lipolidón: fantomima. – Guatemala City : Américana, 1935.

- Imágenes de nacimiento. – 1935

- Essays

- Sociología guatemalteca: El problema social del indio. – Guatemala City Sánchez y de Guise, 1923 (Guatemalan Sociology : The Social Problem of the Indian / translated by Maureen Ahern. – Tempe : Arizona State University Center for Latin American Studies, 1977)

- La arquitectura de la vida nueva. – Guatemala City : Goubaud, 1928

- Carta aérea a mis amigos de América. – Buenos Aires : Casa impresora Francisco A. Colombo, 1952

- Rumania; su nueva imagen. – Xalapa : Universidad Veracruzana, 1964

- Latinoamérica y otros ensayos. – Madrid : Guadiana, 1968

- Comiendo en Hungría. – Barcelona : Lumen, 1969

- América, fábula de fábulas y otros ensayos. – Caracas : Monte Avila Editores, 1972

See also

In Spanish: Miguel Ángel Asturias para niños

In Spanish: Miguel Ángel Asturias para niños