Jacobo Árbenz facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Jacobo Árbenz

|

|

|---|---|

Árbenz in the 1950s

|

|

| 25th President of Guatemala | |

| In office 15 March 1951 – 27 June 1954 |

|

| Preceded by | Juan José Arévalo |

| Succeeded by | Carlos Enrique Díaz de León |

| Minister of National Defense | |

| In office 15 March 1945 – 20 February 1950 |

|

| President | Juan José Arévalo |

| Chief |

|

| Preceded by | Position established;

Francisco Javier Arana as Secretary of Defense

|

| Succeeded by | Rafael O'Meany |

| Head of State and Government of Guatemala | |

| In office 20 October 1944 – 15 March 1945 Serving with Francisco Javier Arana and Jorge Toriello

|

|

| Preceded by | Federico Ponce Vaides |

| Succeeded by | Juan José Arévalo |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán

14 September 1913 Quetzaltenango, Guatemala |

| Died | 27 January 1971 (aged 57) Mexico City, Mexico |

| Resting place | Guatemala City General Cemetery |

| Political party | Revolutionary Action |

| Spouse |

Maria Cristina Vilanova

(m. 1939) |

| Children | 3, including Arabella |

| Alma mater | Polytechnic School of Guatemala |

| Signature | |

| Website | (tribute) |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | Guatemalan Army |

| Years of service | 1932–1954 |

| Rank | Colonel |

| Unit | Guardia de Honor |

| Battles/wars |

|

Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán (born September 14, 1913 – died January 27, 1971) was a military officer and politician from Guatemala. He became the 25th president of Guatemala. Before that, he was the Minister of National Defense from 1944 to 1950. He was the second president of Guatemala to be chosen by the people in a democratic election, serving from 1951 to 1954.

Árbenz was a key leader in the ten-year period known as the Guatemalan Revolution. This time brought some of the only years of true democracy to Guatemala. As president, Árbenz started an important program called agrarian reform. This program, which changed how land was owned, had a big impact across Latin America.

Árbenz was born into a wealthy family in 1913. His father was Swiss German, and his mother was Guatemalan. He finished military school with high honors in 1935. He served in the army until 1944, moving up quickly in rank. During this time, he saw how the dictator Jorge Ubico treated farm workers badly. This experience helped shape his ideas about fairness. In 1938, he married María Vilanova, who greatly influenced his beliefs.

In October 1944, Árbenz and other military leaders, along with everyday citizens, rebelled against Ubico. After this, Juan José Arévalo was elected president. Arévalo started many popular social reforms. Árbenz became his Minister of Defense. He helped stop a military takeover attempt in 1949.

After another leader, Francisco Arana, died, Árbenz ran for president in 1950. He easily won against his main opponent, Miguel Ydígoras Fuentes. Árbenz became president on March 15, 1951. He continued the social reforms started by Arévalo. These changes included giving more people the right to vote. They also allowed workers to form groups and political parties to be legal.

The most important part of his plan was the agrarian reform law. This law took unused parts of very large landholdings. The owners were paid for this land. Then, it was given to poor farm workers. About 500,000 people benefited from this law. Most of them were indigenous people whose families had lost their land long ago.

Árbenz's policies caused problems with the United Fruit Company. This large American company asked the United States government to remove him from power. The U.S. was also worried about some communists in the Guatemalan government. Árbenz was removed from office in 1954 in a takeover planned by the U.S. government. After this, Árbenz lived in exile in different countries. He died in Mexico in 1971. In 2011, the Guatemalan government officially apologized for his overthrow.

Contents

Early Life of Jacobo Árbenz

Jacobo Árbenz was born in Quetzaltenango, Guatemala's second-largest city, in 1913. His father, Hans Jakob Arbenz Gröbli, was a pharmacist from Switzerland. He moved to Guatemala in 1901. Jacobo's mother, Octavia Guzmán Caballeros, was a Guatemalan teacher from a middle-class family.

His family was quite wealthy. His childhood was described as "comfortable." But at some point, his father's business failed. The family lost their money and had to move to a friend's farm. Jacobo had wanted to be an economist or an engineer. However, because his family was now poor, he could not afford to go to a university.

He didn't want to join the military at first. But there was a scholarship available at the Polytechnic School of Guatemala for military students. He applied, passed the tests, and became a cadet in 1932. His father passed away two years after Jacobo joined the academy.

Military Career and Marriage

Árbenz was an excellent student at the military academy. He earned the highest honor given to cadets, called "first sergeant." Only six people received this honor between 1924 and 1944. His skills earned him a lot of respect from the officers at the school.

After graduating in 1935, he worked as a junior officer. He was stationed at Fort San José in Guatemala City. Later, he served in a small village called San Juan Sacatepéquez. At Fort San José, Árbenz had to lead groups of soldiers. They escorted prisoners, including political prisoners, to do forced labor. This experience was very difficult for Árbenz. He said he felt like a "foreman." During this time, he first met Francisco Arana.

In 1937, Árbenz was asked to teach at the academy. He taught many subjects, like military topics, history, and physics. Six years later, he was promoted to captain. He was put in charge of all the cadets. This was a very important position for a young officer.

In 1938, he met María Vilanova, who would become his wife. She came from a wealthy family in El Salvador and Guatemala. They got married a few months later. María's parents did not approve because Jacobo was an army lieutenant and not rich. María was 24 and Jacobo was 26 when they married. María later wrote that they were different but shared a desire for political change.

Árbenz said his wife had a big influence on him. Through her, he learned about Marxism, a way of thinking about society and economics. María left a copy of The Communist Manifesto for him to read. Jacobo was "moved" by it. He and María talked about it a lot. They felt it explained many things they had been feeling. After this, Jacobo read more books by Marx and others. By the late 1940s, he was often talking with a group of Guatemalan communists.

October Revolution and Defense Minister

Historical Background of the Revolution

In 1871, the government of Justo Rufino Barrios took land from the native Mayan people. It forced them to work on coffee farms for very little pay. American companies, like the United Fruit Company, received this public land. They also didn't have to pay taxes.

In 1929, the Great Depression caused the economy to crash. Many people lost their jobs. This led to unrest among workers. To stop a revolution, the wealthy landowners supported Jorge Ubico. He won the election in 1931, where he was the only candidate. With help from the United States, Ubico became a very harsh dictator.

Ubico ended the system where people worked to pay off debts. Instead, he made a vagrancy law. This law forced all working-age men who didn't own land to do at least 100 days of hard labor. The government also used unpaid indigenous labor for public projects like roads. Ubico kept wages very low. He also passed a law that protected landowners. They could not be punished for anything they did to protect their land, even if it meant killing workers. These laws made farm workers very angry. Ubico gave away 200,000 hectares (about 494,000 acres) of public land to the United Fruit Company. He also let the U.S. military build bases in Guatemala.

The October Revolution

In May 1944, protests against Ubico started at the university in Guatemala City. Ubico reacted by stopping the constitution on June 22, 1944. The protests grew bigger, including many middle-class people and army officers. This forced Ubico to resign at the end of June.

Ubico chose a three-person group, led by General Federico Ponce Vaides, to take over. Ponce Vaides first promised free elections. But when the congress met, soldiers forced them to name Ponce Vaides as temporary president. His government continued Ubico's harsh policies.

Opposition groups started organizing again. Many important political and military leaders joined them. Árbenz was one of the few officers who spoke out against Ponce Vaides. Ubico had fired Árbenz from his teaching job. So, Árbenz had been living in El Salvador, organizing a group of revolutionaries. Árbenz was a leader in the army's plan to overthrow the government. He insisted that civilians also be part of the plan.

On October 19, 1944, a small group of soldiers and students attacked the National Palace. This event became known as the "October Revolution." Árbenz and Francisco Javier Arana led this attack. The next day, other army groups and civilians joined them. The revolutionaries eventually defeated the police and army groups loyal to Ponce Vaides. On October 20, Ponce Vaides surrendered. Árbenz and Arana fought bravely. Árbenz was promoted from captain to lieutenant colonel, and Arana from major to full colonel.

The new leaders promised free elections for president and congress. This moment is seen as the start of the Guatemalan Revolution. However, the new government did not immediately threaten the wealthy landowners. Two days after Ponce Vaides resigned, a violent protest happened in a small Indian village. The new government quickly stopped the protest with force.

Elections were held in December 1944. Only men who could read and write were allowed to vote. But the elections were generally fair. None of the temporary leaders ran for president. The winner was a teacher named Juan José Arévalo. He ran with a group of left-leaning parties called the "Revolutionary Action Party" (PAR). He won 85% of the votes.

Arana did not want to give power to a civilian government. He tried to get Árbenz to delay the election. After Arévalo won, Arana asked them to say the results were not valid. But Árbenz insisted that Arévalo should take power. Arana finally agreed, but only if he remained the unchallenged commander of the military. Arévalo had to agree. So, the new Guatemalan constitution, made in 1945, created a powerful position called "Commander of the Armed Forces." This role was more powerful than the defense minister. When Arévalo became president, Arana took this new position. Árbenz became the defense minister.

Juan José Arévalo's Government

Arévalo called his ideas "spiritual socialism." He was against communism. He believed in a capitalist society where the government helped make sure everyone benefited. Arévalo's ideas were put into the new constitution, which was very modern for Latin America. It gave voting rights to most people, spread out government power, and allowed many political parties. However, communist parties were not allowed.

Once in office, Arévalo made many changes. These included laws for minimum wage, more money for education, and worker rights. But these changes mostly helped the upper-middle classes. They did not do much for the poor farm workers who were most of the population. Even though his changes were based on capitalism, the United States government was suspicious of him. They later called him a communist.

When Árbenz became defense minister under President Arévalo, he was the first to hold this job. Before, it was called the "Ministry of War." In 1947, Árbenz disagreed with deporting some workers who were accused of being communists. A well-known communist, José Manuel Fortuny, was interested in this. He visited Árbenz and found him different from other military officers. They met many times, and Árbenz invited Fortuny to his house for long talks. Like Árbenz, Fortuny strongly wanted to improve life for Guatemalan people. He also looked for answers in Marxist ideas. This friendship would greatly influence Árbenz later on.

In December 1945, Arévalo was hurt in a car accident. Leaders of the Revolutionary Action Party (PAR) worried that Arana would try to take power. So, they made a deal with him, called the Pacto del Barranco (Pact of the Ravine). Arana agreed not to seize power. In return, the PAR agreed to support Arana for president in the next election in 1950. Arévalo recovered quickly but had to support this deal.

However, by 1949, many political parties were against Arana. This was because he did not support worker rights. The left-leaning parties decided to support Árbenz instead. They believed only a military officer could defeat Arana. In 1947, Arana had demanded that some labor leaders be sent out of the country. Árbenz openly disagreed with Arana, and his actions limited how many people were deported.

The land reforms started by Arévalo worried the wealthy landowners. They wanted a president who would be more on their side. They began to support Arana as a leader against Arévalo's changes. In the summer of 1949, there was a lot of disagreement in the Guatemalan military. Supporters of Arana and Árbenz argued over who would be Arana's successor.

On July 16, 1949, Arana gave Arévalo an ultimatum. He demanded that all of Árbenz's supporters be removed from the government and military. He threatened a takeover if his demands were not met. Arévalo told Árbenz and other leaders about this. They all agreed that Arana should be sent away. Two days later, Arévalo and Arana had another meeting. On the way back, Arana's group was stopped by a small force led by Árbenz. A shootout happened, and three men died, including Arana. Árbenz's supporters in the military tried to rebel, but they had no clear leader. By the next day, the rebels asked to talk. This attempt to take over left about 150 people dead and 200 wounded.

Árbenz and some other ministers wanted to tell the whole truth about Arana's death. But most of the government disagreed. Arévalo made a speech suggesting Arana was killed because he refused to lead a takeover against the government. Árbenz stayed silent about Arana's death until 1968. He refused to speak without Arévalo's permission. He tried to convince Arévalo to tell the full story when they met in exile. But Arévalo did not want to, and Árbenz did not push him.

The 1950 Election

Árbenz's role as defense minister already made him a strong candidate for president. His strong support for the government during the 1949 uprising made him even more respected. In 1950, the National Integrity Party (PIN) announced that Árbenz would be their candidate for president. Soon after, most left-leaning parties and labor unions supported him. Árbenz chose the PIN carefully to make his candidacy seem more moderate.

Árbenz resigned as Defense Minister on February 20 and announced he was running for president. Arévalo wrote him a supportive letter. However, Arévalo publicly supported him only reluctantly. He preferred his friend Víctor Manuel Giordani, who was the Health Minister. But because Árbenz had so much support, Arévalo decided to back him.

Before his death, Arana had planned to run in the 1950 election. His death left Árbenz without any serious opponents. Árbenz had only a few main challengers among ten candidates. One was Miguel Ydígoras Fuentes, a general under Ubico. He had the support of those who strongly opposed the revolution. During his campaign, Árbenz promised to continue and expand the reforms started by Arévalo.

Árbenz was expected to win easily. He had the support of the country's two main political parties and the labor unions. They campaigned hard for him. Besides political support, Árbenz was also very appealing personally. He was described as having a "charming personality and a strong voice." Árbenz's wife, María, also campaigned with him. Even though she came from a wealthy background, she spoke for the Mayan farmers. She became a national figure. Árbenz's two daughters also sometimes appeared with him in public.

The election was held on November 15, 1950. Árbenz won more than 60% of the votes. The elections were largely fair, except that illiterate women could not vote. Árbenz received more than three times as many votes as the runner-up, Ydígoras Fuentes. Fuentes claimed there was fraud, but experts say that even if there was some fraud, it wasn't why Árbenz won. Árbenz's promise of land reform was a big reason for his victory.

Árbenz became president on March 15, 1951.

Jacobo Árbenz's Presidency

Inauguration and Goals

In his first speech as president, Árbenz promised to change Guatemala. He wanted to turn it from "a backward country with a mostly feudal economy into a modern capitalist state." He said he would make Guatemala less dependent on foreign markets. He also wanted to reduce the power of foreign companies in Guatemalan politics. He planned to improve Guatemala's roads, ports, and houses without foreign money.

Árbenz also aimed to fix Guatemala's economy. He planned to build factories, increase mining, and improve transportation. He also wanted to expand the banking system. Land reform was the most important part of Árbenz's election promises. The groups that helped Árbenz get elected kept pushing him to keep his promises about land reform. When Árbenz took office, only 2% of the people owned 70% of the land.

Historian Jim Handy described Árbenz's economic and political ideas as "very practical and capitalist." According to historian Stephen Schlesinger, Árbenz "was not a dictator, he was not a secret communist." Schlesinger called him a democratic socialist. However, some of his policies, especially land reform, were called "communist" by Guatemala's wealthy class and the United Fruit Company.

Historian Piero Gleijeses said that Árbenz's policies were meant to be capitalist. But his personal beliefs slowly moved towards communism. His main goal was to make Guatemala more economically and politically independent. He believed that Guatemala needed a strong local economy to do this. He tried to connect with the indigenous Mayan people. He sent government officials to talk with them. From this, he learned that the Maya strongly valued their dignity and self-rule. Inspired by this, he said in 1951, "If the independence and wealth of our people were not compatible, which they certainly are, I am sure that most Guatemalans would rather be a poor nation, but free, than a rich colony, but enslaved."

Even though Árbenz's government policies were based on a moderate form of capitalism, the communist movement did grow stronger during his presidency. This was partly because Arévalo had released its imprisoned leaders in 1944. Also, the teachers' union, which was strong, helped. The Communist party was banned for much of the Guatemalan Revolution. But the Guatemalan government welcomed many communist and socialist refugees from other countries. This helped the local movement grow.

Árbenz also had personal connections to some members of the communist Guatemalan Party of Labour, which became legal during his government. The most important of these was José Manuel Fortuny. Fortuny was a friend and adviser to Árbenz during his three years in office. Fortuny wrote some speeches for Árbenz. As agricultural secretary, he helped create the important land reform law. However, Fortuny was never very popular in Guatemala. The communist party remained small and had no members in Árbenz's main government team. A few communists were given lower-level jobs in the government.

Árbenz read and admired the writings of Marx, Lenin, and Stalin. Officials in his government praised Stalin as a "great statesman and leader... whose passing is mourned by all progressive men." The Guatemalan Congress honored Joseph Stalin with a "minute of silence" when he died in 1953. Árbenz had some supporters among the communist members of the legislature. But they were only a small part of the government's group of supporters.

Land Reform Program

The biggest part of Árbenz's plan to modernize Guatemala was his land reform law. Árbenz wrote the law himself. He got help from advisers, including some communist leaders and non-communist economists. He also asked for advice from many economists across Latin America. The National Assembly passed the law on June 17, 1952. The program started right away.

It took unused land from very large landowners. This land was then given to poor farm workers. These workers could then start their own farms. Árbenz also wanted to pass this law to get money for his public building projects in the country. The World Bank had refused to give Guatemala a loan in 1951, which made the shortage of money worse.

The official name of the land reform law was Decree 900. It took all unused land from properties larger than 673 acres (272 hectares). If properties were between 224 acres (91 hectares) and 672 acres (272 hectares), unused land was taken only if less than two-thirds of it was being used. The owners were paid with government bonds. The value of these bonds was equal to the value of the land. The land's value was what the owners had said it was on their tax forms in 1952.

Local committees organized the land distribution. These committees included representatives from landowners, workers, and the government. Out of almost 350,000 private landholdings, only 1,710 were affected by the law. The law itself was based on moderate capitalist ideas. However, it was put into action very quickly. This sometimes led to land being taken unfairly. There was also some violence against landowners and even against peasants who owned small amounts of land. Árbenz himself, who owned land through his wife, gave up 1,700 acres (6.9 square kilometers) of his own land for the program.

By June 1954, 1.4 million acres (566,560 hectares) of land had been taken and given out. About 500,000 people, or one-sixth of the population, had received land by this time. The law also gave financial help to the people who received land. The National Agrarian Bank (BNA) was created on July 7, 1953. By June 1951, it had given out more than $9 million in small loans. 53,829 people received an average of $225. This was twice the average income in Guatemala. The BNA became known as a very efficient government office. Even the United States government, which was Árbenz's biggest critic, had nothing bad to say about it. The loans were paid back at a high rate. Of the $3,371,185 given out between March and November 1953, $3,049,092 had been paid back by June 1954. The law also allowed the government to take over roads that went through redistributed land. This greatly improved how connected rural communities were.

Against what the government's critics predicted, the law actually led to a small increase in Guatemala's farm production. The amount of land being farmed also increased. Overall, the law greatly improved the lives of thousands of farm families. Most of these families were indigenous people. Historian Piero Gleijeses said that the unfairness corrected by the law was much greater than the unfairness of the few times land was taken unfairly. Historian Greg Grandin said the law had some flaws. For example, it was too careful and too respectful of the planters. It also created divisions among farmers. Still, it meant a big shift in power for those who had been left out before. In 1953, the Supreme Court said the reform was against the constitution. But the Guatemalan Congress later removed four judges who were involved in that ruling.

Relationship with the United Fruit Company

Historians say the relationship between Árbenz and the United Fruit Company was a "critical turning point in US dominance in the hemisphere." The United Fruit Company, started in 1899, owned a lot of land and railroads across Central America. They used these to export bananas. By 1930, it had been the biggest landowner and employer in Guatemala for many years.

In exchange for the company's support, dictator Ubico signed a contract with them. This contract gave the company a 99-year lease to huge areas of land. It also freed them from almost all taxes. Ubico asked the company to pay its workers only 50 cents a day. This was to stop other workers from asking for higher wages. The company also practically owned Puerto Barrios, Guatemala's only port to the Atlantic Ocean. By 1950, the company's yearly profits were $65 million. This was twice the income of the Guatemalan government.

Because of this, the company was seen as a barrier to progress by the revolutionary movement after 1944. Since it was the country's largest landowner and employer, Arévalo's government reforms affected the United Fruit Company more than other companies. This made the company feel like it was being specifically targeted. The company's worker problems got worse in 1952 when Árbenz passed Decree 900, the land reform law. Of the 550,000 acres (222,577 hectares) the company owned, only 15% were being farmed. The rest of the land, which was not being used, came under the new land reform law. Also, Árbenz supported a strike by United Fruit Company workers in 1951. This eventually forced the company to rehire some workers they had laid off.

The United Fruit Company responded by strongly trying to influence the United States government against Árbenz. The Guatemalan government said that the company was the main problem for progress in the country. American historians noted that "to the Guatemalans it appeared that their country was being mercilessly exploited by foreign interests which took huge profits without making any contributions to the nation's welfare."

In 1953, 200,000 acres (80,937 hectares) of unused land were taken from the company under Árbenz's land reform law. The company was offered $2.99 per acre as payment. This was twice what they had paid for the land. This led to more efforts to influence Washington, especially through Secretary of State John Foster Dulles. He had close ties to the company. The company started a public relations campaign to make the Guatemalan government look bad. Overall, the company spent over half a million dollars to convince lawmakers and the public in the U.S. that Jacobo Árbenz's government needed to be overthrown.

The 1954 Coup d'état

Reasons for the Coup

Several things, besides the United Fruit Company's efforts, led the United States to plan the takeover that removed Árbenz in 1954. The U.S. government became more suspicious of the Guatemalan Revolution as the Cold War grew. The Guatemalan government also had more disagreements with U.S. companies. The U.S. was also worried that communists had influenced the government. However, historian Richard H. Immerman said that early in the Cold War, the U.S. and the CIA were ready to see the revolutionary government as communist, even though Arévalo had banned the communist party.

Also, the U.S. government was concerned that Árbenz's successful reforms would inspire similar movements in other countries. Until the end of its term, the Truman administration tried to reduce communist influences using only diplomacy and economic means.

Árbenz's new land law, Decree 900, in 1952, made Truman allow Operation PBFortune. This was a secret plan to overthrow Árbenz. The plan was first suggested by Anastasio Somoza García, the U.S.-backed dictator of Nicaragua. He said he could overthrow the Guatemalan government if he was given weapons. The operation was to be led by Carlos Castillo Armas. However, the U.S. State Department found out about the plan. Secretary of State Dean Acheson convinced Truman to stop it.

After being elected U.S. president in November 1952, Dwight Eisenhower was more willing than Truman to use military force to remove governments he didn't like. Several people in his government had close ties to the United Fruit Company. These included Secretary of State John Foster Dulles and his brother, CIA director Allen Dulles. John Foster Dulles had been a lawyer for the United Fruit Company. His brother, Allen Dulles, was on the company's board of directors. These connections made the Eisenhower administration more willing to overthrow the Guatemalan government.

Operation PBSuccess

The CIA's plan to overthrow Jacobo Árbenz was called Operation PBSuccess. Eisenhower approved it in August 1953. Carlos Castillo Armas, who had been Arana's assistant and exiled after a failed takeover in 1949, was chosen to lead the coup. Castillo Armas gathered about 150 fighters from Guatemalan exiles and people from nearby countries.

In January 1954, news of these plans leaked to the Guatemalan government. They said a "Government of the North" was plotting to overthrow Árbenz. The U.S. government denied this. The U.S. media supported their government, saying Árbenz had fallen for communist propaganda. The U.S. stopped selling weapons to Guatemala in 1951. Soon after, it blocked Guatemala from buying weapons from Canada, Germany, and Rhodesia. By 1954, Árbenz desperately needed weapons. He decided to buy them secretly from Czechoslovakia. The CIA presented this as Soviet interference in the Americas. This was the final push for the CIA to launch its coup.

Árbenz wanted the weapons from the Alfhem ship to arm peasant groups. This was in case the army was disloyal. But the U.S. told the Guatemalan army leaders about the shipment. This forced Árbenz to give the weapons to the military. This made the split between him and his army leaders even deeper.

Castillo Armas' forces invaded Guatemala on June 18, 1954. The invasion came with a strong campaign of psychological warfare. This campaign made it seem like Castillo Armas' victory was already decided. Its goal was to force Árbenz to resign. The most powerful psychological tool was a radio station called the "Voice of Liberation." It broadcast news of rebel troops moving towards the capital. This caused great fear among both the army and the people.

Árbenz was confident that Castillo Armas could be defeated militarily. But he worried that defeating Castillo Armas would cause a U.S. invasion. Árbenz ordered Carlos Enrique Díaz, the army chief, to choose officers to lead a counter-attack. Díaz chose officers known for their honesty and loyalty to Árbenz.

By June 21, Guatemalan soldiers had gathered at Zacapa. They were under the command of Colonel Víctor M. León, who was thought to be loyal to Árbenz. The communist party leaders also became suspicious. They sent a member to investigate. He returned on June 25, reporting that the army was very discouraged and would not fight. The head of the communist party told Árbenz. Árbenz quickly sent his own investigator. He brought back a message asking Árbenz to resign. The officers believed that with U.S. support for the rebels, defeat was unavoidable. The message said that if Árbenz did not resign, the army would likely make a deal with Castillo Armas.

On June 25, Árbenz announced that the army had abandoned the government. He said civilians needed to be armed to defend the country. However, only a few hundred people volunteered. Seeing this, Díaz stopped supporting the president. He began planning to overthrow Árbenz with other senior army officers. They told U.S. ambassador John Peurifoy about their plan. They asked him to stop the fighting if Árbenz resigned. Peurifoy promised to arrange a truce. The plotters then went to Árbenz and told him their decision.

Árbenz, very tired, wanted to save at least some of the democratic changes he had made. He agreed. After telling his government team, he left the presidential palace at 8 p.m. on June 27, 1954. He had recorded a resignation speech that was broadcast an hour later. In it, he said he was resigning to remove the "reason for the invasion." He wanted to protect the achievements of the October Revolution. He then walked to the nearby Mexican Embassy to ask for political protection.

Later Life in Exile

Beginning of Exile

After Árbenz resigned, his family stayed for 73 days at the Mexican embassy in Guatemala City. The embassy was crowded with almost 300 exiles. During this time, the CIA started new actions against Árbenz. They wanted to make the former president look bad and harm his reputation. The CIA got some of Árbenz's personal papers. They released parts of them after changing the documents. The CIA also pushed the idea that exiles like Árbenz should be put on trial in Guatemala.

When they were finally allowed to leave the country, Árbenz was publicly shamed at the airport. Authorities made the former president take off his clothes in front of cameras. They claimed he was carrying jewelry he bought for his wife, María Cristina Vilanova, with government money. No jewelry was found, but the questioning lasted for an hour. During this whole period, news about Árbenz in the Guatemalan press was very negative. This was largely due to the CIA's campaign.

The family then began a long journey in exile. They went first to Mexico, then to Canada to pick up Arabella (the Árbenzs' oldest daughter). Then they traveled to Switzerland through the Netherlands and Paris. They hoped to become citizens in Switzerland because of Árbenz's Swiss background. However, the former president did not want to give up his Guatemalan nationality. He felt that doing so would end his political career. Árbenz and his family were victims of a strong smear campaign by the CIA. This campaign lasted from 1954 to 1960. A close friend of Árbenz, Carlos Manuel Pellecer, turned out to be a spy for the CIA.

Life in Europe and Uruguay

After not being able to become citizens in Switzerland, the Árbenz family moved to Paris. The French government allowed them to live there for a year. The condition was that they could not take part in any political activities. Then they moved to Prague, the capital of Czechoslovakia. After only three months, he moved to Moscow. This was a relief for him from the harsh treatment he received in Czechoslovakia. While traveling in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, he was constantly criticized in the press in Guatemala and the U.S. They said he was showing his true communist beliefs by going there.

After a short stay in Moscow, Árbenz returned to Prague and then to Paris. From there, he separated from his wife. María traveled to El Salvador to handle family matters. The separation made life increasingly difficult for Árbenz. He tried several times to return to Latin America. Finally, in 1957, he was allowed to move to Uruguay. The CIA tried several times to stop Árbenz from getting a Uruguayan visa. But they were not successful. The Uruguayan government allowed Árbenz to travel there as a political refugee. Árbenz arrived in Montevideo on May 13, 1957. There, he was met by a hostile "welcome committee" organized by the CIA. However, he was still an important figure in left-wing groups in the city. This partly explains the CIA's hostility.

While Árbenz was living in Montevideo, his wife came to join him. Arévalo also visited him a year after Árbenz arrived. At first, the relationship between Arévalo and the Árbenz family was friendly. But it soon got worse because of differences between the two men. Arévalo himself was not watched closely in Uruguay. He was sometimes able to share his thoughts through articles in popular newspapers. He left for Venezuela a year after arriving to take a teaching job. During his stay in Uruguay, Árbenz was first required to report to the police every day. Eventually, this rule was relaxed to once every eight days. María Árbenz later said that the couple was happy with the kindness they received in Uruguay. They would have stayed there forever if they had been allowed.

Guatemalan Government Apology

In 1999, the Árbenz family went to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR). They asked for an apology from the Guatemalan government for the 1954 coup that removed him from power. After years of campaigning, the Árbenz Family took the Guatemalan Government to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights in Washington, D.C. The Commission accepted the complaint in 2006. This led to five years of on-and-off talks.

In May 2011, the Guatemalan government signed an agreement with Árbenz's surviving family. The agreement was to restore his good name and publicly apologize for the government's role in his overthrow. This included money for the family. The family also insisted on social repairs and policies for the future of the Guatemalan people. This was a first for a judgment of this kind from the OAS.

The official apology was made at the National Palace by Guatemalan President Alvaro Colom on October 20, 2011. He apologized to Jacobo Árbenz Vilanova, the son of the former president and a Guatemalan politician. Colom stated, "It was a crime to Guatemalan society and it was an act of aggression to a government starting its democratic spring."

The agreement set up several ways to make amends for Árbenz Guzmán's family. Among other things, the state:

- held a public ceremony to admit its responsibility

- sent a letter of apology to the family

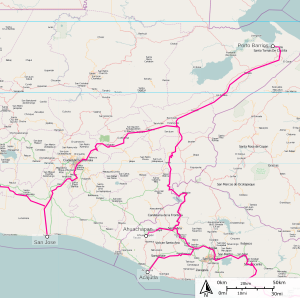

- named a hall of the National Museum of History and the highway to the Atlantic after the former president

- updated the national school curriculum

- created a university program in Human Rights, Pluriculturalism, and Reconciliation of Indigenous Peoples

- held a photo exhibition about Árbenz Guzmán and his impact at the National Museum of History

- brought back the many photos of the Árbenz Guzmán family

- published a book of photos

- reissued the book Mi esposo, el presidente Árbenz (My Husband President Árbenz)

- prepared and published a biography of the former president, and

- issued a series of postage stamps in his honor.

The government's official statement admitted its responsibility for "failing to comply with its obligation to guarantee, respect, and protect the human rights of the victims to a fair trial, to property, to equal protection before the law, and to judicial protection, which are protected in the American Convention on Human Rights and which were violated against former President Juan Jacobo Árbenz Guzman, his wife, María Cristina Villanova, and his children, Juan Jacobo, María Leonora, and Arabella, all surnamed Árbenz Villanova."

Legacy of Jacobo Árbenz

Historian Roberto García Ferreira wrote in 2008 that Árbenz's legacy is still much debated in Guatemala. He argued that Árbenz's image was greatly shaped by the CIA's media campaign after the 1954 coup. García Ferreira said that the revolutionary government was one of the few times when "state authority was used to promote the interests of the nation's masses."

Historian Cindy Forster described Árbenz's legacy this way: "In 1952 the Agrarian Reform Law swept the land, destroying forever the power of the planters. Árbenz effectively created a new social order... The revolutionary decade... plays a central role in twentieth-century Guatemalan history because it was more complete than any period of reform before or since." She added that even within the Guatemalan government, Árbenz "gave full scope to Indigenous, campesino, and labor demands." This was different from Arévalo, who had been suspicious of these movements.

Similarly, Greg Grandin stated that the land reform law "represented a fundamental shift in the power relations governing Guatemala." Árbenz himself once said that the land reform law was "the most precious fruit of the revolution and the fundamental base of the nation as a new country." However, many of the laws and changes made by the Árbenz and Arévalo governments were undone by the military governments that followed, which were supported by the U.S.

See also

In Spanish: Jacobo Árbenz para niños

In Spanish: Jacobo Árbenz para niños

- Salvador Allende - Socialist president of Chile who was removed in a US-supported takeover

- Juan José Torres - Socialist president of Bolivia removed by a US-supported takeover

- Ernest V. Siracusa - Embassy official in Guatemala who later was ambassador in Bolivia during the coup against Torres

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |