Carlos Castillo Armas facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Carlos Castillo Armas

|

|

|---|---|

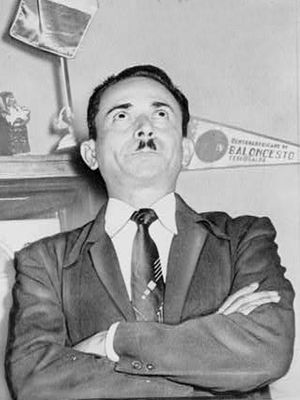

Castillo Armas in 1954

|

|

| 28th President of Guatemala | |

| In office 7 July 1954 – 26 July 1957 |

|

| Preceded by | Elfego Hernán Monzón Aguirre |

| Succeeded by | Luis González López |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 4 November 1914 Santa Lucía Cotzumalguapa, Guatemala |

| Died | 26 July 1957 (aged 42) Guatemala City, Guatemala |

| Cause of death | Assassination |

| Political party | National Liberation Movement |

| Spouse | Odilia Palomo Paíz |

| Occupation | Military officer |

| Signature |  |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | Guatemalan Army |

| Years of service | 1933 – 1949 |

| Rank | Lieutenant colonel |

| Battles/wars | 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état |

| Awards | Mentioned in dispatches (1946) Medal of Military Merit (Mexico) (first class; 1948) |

Carlos Castillo Armas (born November 4, 1914 – died July 26, 1957) was a military officer and politician from Guatemala. He became the 28th President of Guatemala in 1954 after taking power in a military takeover. He led the National Liberation Movement (MLN) party, which was a right-wing group. His government was very strict and had a close relationship with the United States.

Castillo Armas grew up as the son of a landowner and went to Guatemala's military academy. He joined forces with Colonel Francisco Javier Arana during a revolt in 1944 against President Federico Ponce Vaides. This event started the Guatemalan Revolution, which brought representative democracy to the country. Castillo Armas later became the director of the military academy.

Both Arana and Castillo Armas did not support the new government led by President Juan José Arévalo. After Arana's attempt to overthrow the government failed in 1949, Castillo Armas went to live in Honduras. There, he sought help for another revolt and caught the attention of the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). In 1950, he tried to attack Guatemala City but failed and went back to Honduras.

The US government, influenced by the United Fruit Company and fears of communism during the Cold War, planned to remove President Jacobo Árbenz in 1952. This plan, called Operation PBFortune, was supposed to be led by Castillo Armas. Although it was stopped, a new plan was started by US President Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1953.

In June 1954, Castillo Armas led about 480 soldiers, trained by the CIA, into Guatemala. They had support from US planes. Even though the rebels faced problems at first, the US support made the Guatemalan army hesitant to fight. President Árbenz resigned on June 27. After some military groups briefly held power, Castillo Armas became president on July 7.

Castillo Armas made his power stronger in an election in October 1954, where he was the only candidate. His party, the MLN, was the only one allowed in the elections for Congress. He largely reversed Árbenz's popular land reform, taking land from small farmers and giving it back to large landowners. He also cracked down on unions and farmer groups, leading to many arrests and deaths. He created a group called the National Committee of Defense Against Communism, which investigated over 70,000 people.

Despite his efforts, Castillo Armas faced a lot of resistance within the country. His government struggled with corruption and rising debt, becoming very dependent on aid from the US. In 1957, Castillo Armas was shot and killed by a presidential guard. He was the first of several strict rulers in Guatemala who were close allies of the US. His actions to undo the reforms of earlier leaders led to many revolts after his death, which eventually caused the Guatemalan Civil War from 1960 to 1996.

Contents

Early Life and Military Career

Carlos Castillo Armas was born on November 4, 1914, in Santa Lucía Cotzumalguapa, a town in the Escuintla region. His father was a landowner, but because Carlos was born outside of marriage, he could not inherit the family property. In 1936, he finished his studies at the Guatemalan military academy. Jacobo Árbenz, who would later become president, was also at the academy during Castillo Armas's time there.

In June 1944, many public protests led to the dictator Jorge Ubico stepping down. Ubico's replacement, Federico Ponce Vaides, promised fair elections but continued to stop people from speaking out. This made some progressive army officers plan to overthrow him. The plan was first led by Árbenz. On October 19, Arana and Árbenz launched a coup against Ponce Vaides' government. In the election that followed, Juan José Arévalo became president. Castillo Armas strongly supported Arana and joined the rebels. Árbenz later said that Castillo Armas was "modest, brave, sincere" and fought with "great bravery" during the coup.

For seven months, from October 1945 to April 1946, Castillo Armas trained at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, in the United States. There, he met American intelligence officers. After working on the General Staff, he became the director of the military academy until early 1949. Then, he was made the military commander in Mazatenango, a distant military base. Castillo Armas eventually reached the rank of lieutenant colonel.

He was in Mazatenango when Arana tried and failed to overthrow President Arévalo on July 18, 1949. Arana was killed during this attempt. Historians have different ideas about what happened to Castillo Armas next. Some say he was sent out of the country after the coup attempt. Others say he was arrested in August 1949 and held in prison until December 1949, then found in Honduras a month later.

CIA Connections and Early Plans

After President Arévalo's popular term ended in 1951, Jacobo Árbenz was elected president. He continued Arévalo's reforms and started a big land reform program called Decree 900. This law took unused parts of large landholdings, paid the owners for them, and gave the land to poor farm workers. This land reform made the United Fruit Company very angry. This company controlled a large part of Guatemala's economy at the time. The company had received many favors from previous governments, including huge amounts of public land and no taxes.

Feeling threatened by Árbenz's reforms, the company started a strong campaign to influence the US government. The Cold War also made the US government, led by President Harry Truman, see the Guatemalan government as communist. The US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) began to think about supporting people who opposed Árbenz.

Castillo Armas first met the CIA in January 1950. A CIA officer learned that he was trying to get weapons from Anastasio Somoza García and Rafael Trujillo, who were strict rulers of Nicaragua and the Dominican Republic. The CIA officer described Castillo Armas as "a quiet, soft-spoken officer." Castillo Armas met with the CIA a few more times before November 1950. He told the CIA that he had support from the Civil Guard and army leaders in Guatemala City.

A few days after his last meeting with the CIA, Castillo Armas led an attack against a fortress in Guatemala City with a few supporters. The attack failed, and Castillo Armas was hurt and arrested. A year later, he paid his way out of prison and escaped back to Honduras. His stories of revolt and escape became popular among Guatemalan exiles in Honduras. Castillo Armas claimed he still had support in the army and began planning another revolt.

The CIA sent an engineer to talk with Castillo Armas. The engineer reported that Castillo Armas had financial help from Somoza and Trujillo. President Truman then approved a plan called Operation PBFortune. Castillo Armas proposed a plan to the CIA: three forces would invade Guatemala from Mexico, Honduras, and El Salvador, supported by rebellions inside the country. The CIA planned to give Castillo Armas $225,000, weapons, and transportation. Other leaders, like Trujillo and Marcos Pérez Jiménez of Venezuela, also agreed to help with money. However, this coup attempt was stopped by Dean Acheson, the US Secretary of State, before it could be finished.

The CIA continued to pay Castillo Armas $3,000 a week, which allowed him to keep a small group of followers. This money was also meant to stop him from acting too soon. Even after the operation was stopped, the CIA received reports that Guatemalan rebels were planning to remove political and military leaders. Castillo Armas planned to use soldiers in civilian clothes from Nicaragua, Honduras, and El Salvador for this purpose.

The 1954 Coup d'état

Planning the Takeover

In November 1952, Dwight Eisenhower became president of the US. He promised to be tougher on communism. Important people in his government, like Secretary of State John Foster Dulles and CIA director Allen Dulles, had close ties to the United Fruit Company. This made Eisenhower more likely to support overthrowing Árbenz. These factors led the Eisenhower government to approve "Operation PBSuccess" to remove the Guatemalan government in August 1953.

This operation had a budget of $5 million to $7 million. It involved many CIA agents and local people recruited in Guatemala. The plans included lists of people in Árbenz's government who would be removed if the coup happened. A team of diplomats was formed to support PBSuccess. The leader of this team was John Peurifoy, who became the US ambassador to Guatemala in October 1953.

The CIA considered several people to lead the coup. Miguel Ydígoras Fuentes, a conservative who lost the 1950 election to Árbenz, was popular with the opposition. But he was rejected because of his past role in the Ubico government and his European looks, which might not appeal to most Guatemalans. Castillo Armas, however, was described as a "physically unimposing man with marked mestizo features" (meaning he had mixed Indigenous and European heritage). Another possible leader was coffee farmer Juan Córdova Cerna, but he got throat cancer, so he was out of the running.

This led to the choice of Castillo Armas, who had been living in exile since the failed coup in 1949. Castillo Armas had been paid by the CIA since the earlier Operation PBFortune in 1951. Historians say that the CIA saw Castillo Armas as the most reliable leader. He also had the support of Guatemala's archbishop. In CIA documents, he was called "Calligeris."

Castillo Armas received enough money to gather a small group of about 150 fighters from Guatemalan exiles and people from nearby countries. This group was called the "Army of Liberation." The CIA set up training camps in Nicaragua and Honduras and gave them weapons and planes flown by American pilots. Before the invasion, the US signed military agreements with Nicaragua and Honduras, allowing them to move heavy weapons easily. These preparations were not very secret; the CIA wanted Árbenz to know about them. This was part of their plan to convince Guatemalans that Árbenz's overthrow was unavoidable.

Castillo Armas's army was not big enough to defeat the Guatemalan military on its own. So, Operation PBSuccess also included a plan to use psychological warfare. This meant making people believe that Castillo Armas's victory was already decided, which would force Árbenz to resign. The US propaganda campaign started long before the invasion. The United States Information Agency wrote many articles about Guatemala based on CIA reports and handed out thousands of leaflets across Latin America.

The most powerful psychological tool was a radio station called the "Voice of Liberation." This station began broadcasting on May 1, 1954. It sent out anti-communist messages and told listeners to resist the Árbenz government and support Castillo Armas's forces. The station claimed to be broadcasting from deep inside Guatemala's jungles, and many listeners believed this. But actually, the broadcasts were created in Miami by Guatemalan exiles and sent through a mobile transmitter in Central America.

The Invasion Begins

Castillo Armas's force of 480 men was divided into four groups, ranging from 60 to 198 soldiers. On June 15, 1954, these groups left their bases in Honduras and El Salvador and gathered in towns near the Guatemalan border. The largest group was meant to attack the port town of Puerto Barrios. The others were to attack smaller towns like Esquipulas, Jutiapa, and Zacapa, which was the Guatemalan Army's biggest border post.

The invasion plan quickly ran into problems. A group of 60 men was stopped and jailed by Salvadoran police before they even reached the border. At 8:20 AM on June 18, 1954, Castillo Armas led his troops across the border. Ten trained saboteurs went ahead to blow up railways and cut telegraph lines. Around the same time, Castillo Armas's planes flew over a pro-government rally in the capital. Castillo Armas demanded that Árbenz surrender immediately. The invasion caused a brief panic in the capital, but it quickly lessened as the rebels failed to make much progress. Walking and carrying heavy weapons, Castillo Armas's forces took several days to reach their targets, though their planes did blow up a bridge on June 19.

When the rebels finally reached their targets, they faced more difficulties. The group of 122 men heading for Zacapa was stopped and badly beaten by a small group of 30 loyal soldiers. Only 30 rebels escaped. The group that attacked Puerto Barrios was defeated by police and armed dockworkers, with many rebels fleeing back to Honduras. To regain momentum, the rebels attacked the capital with their planes. These attacks caused little physical damage but had a big psychological effect. Many citizens began to believe that the invasion force was much stronger than it actually was. The CIA also kept broadcasting propaganda from the "Voice of Liberation" station throughout the conflict. It reported news of rebel troops moving towards the capital, which greatly lowered the morale of both the army and the people.

After the Invasion

Árbenz first believed his army would quickly defeat the rebels. The victory of the small Zacapa group made him even more confident. However, the CIA's psychological warfare made the army unwilling to fight Castillo Armas. Historians say that without US support, the Guatemalan army officers would have stayed loyal to Árbenz. They had strong nationalist feelings and did not want foreign interference. But they believed the US would intervene militarily, leading to a battle they could not win. On June 17, the army leaders at Zacapa began talking with Castillo Armas. They signed an agreement called the Pacto de Las Tunas three days later. This agreement put the army at Zacapa under Castillo Armas in exchange for a general pardon. The army returned to its barracks a few days later, feeling defeated.

Árbenz decided to arm the people to defend the capital, but not enough people volunteered. At this point, Colonel Carlos Enrique Díaz de León, the army's chief of staff, stopped supporting the president. He began planning to overthrow Árbenz with other senior army officers. They told Ambassador Peurifoy about their plan and asked him to stop the fighting if Árbenz resigned. On June 27, 1954, Árbenz met with Díaz and told him he was resigning. Historians note that Castillo Armas's invasion itself was not the main threat to Árbenz. Instead, the coup led by Díaz and the Guatemalan army was the key factor in his removal.

Árbenz left office at 8 PM, after recording a resignation speech that was broadcast an hour later. Immediately after, Díaz announced that he would take over the presidency in the name of the Guatemalan Revolution. He also stated that the Guatemalan army would still fight against Castillo Armas's invasion. Peurifoy had not expected Díaz to continue fighting. A couple of days later, Peurifoy told Díaz that he had to resign. According to a CIA officer, this was because Díaz was "not convenient for American foreign policy." Díaz first tried to calm Peurifoy by forming a ruling group (junta) with Colonel Elfego Monzón and Colonel José Angel Sánchez, led by himself. Peurifoy kept insisting that he resign. Eventually, Díaz was overthrown in a quick, peaceful coup led by Monzón, who was more willing to cooperate.

At first, Monzón did not want to give power to Castillo Armas. The US State Department convinced Óscar Osorio, the president of El Salvador, to invite Monzón, Castillo Armas, and other important people to peace talks in San Salvador. Osorio agreed. After Díaz was removed, Monzón and Castillo Armas arrived in the Salvadoran capital on June 30. Castillo Armas wanted to add some of his rebel forces into the Guatemalan military. Monzón was hesitant about this, which made the talks difficult. Castillo Armas also felt that Monzón had been slow to join the fight against Árbenz. The talks almost broke down on the very first day. So, Peurifoy, who had stayed in Guatemala City to make it seem like the US was not heavily involved, traveled to San Salvador. Allen Dulles later said that Peurifoy's role was to "crack some heads together."

Peurifoy was able to force an agreement because neither Monzón nor Castillo Armas could become or stay president without US support. The deal was announced at 4:45 AM on July 2, 1954. Under its terms, Castillo Armas and his helper, Major Enrique Trinidad Oliva, became members of the junta led by Monzón, though Monzón remained president. The agreement also stated that the five-person junta would rule for fifteen days, during which a president would be chosen. Two members of the junta, Colonels Dubois and Cruz Salazar, who supported Monzón, had signed a secret agreement without Monzón knowing. On July 7, they resigned as part of the agreement. Monzón, left outnumbered on the junta, also resigned. On July 8, Castillo Armas was chosen unanimously as president of the junta. The US quickly recognized the new government on July 13.

Presidency and Assassination

Becoming President

Soon after taking power, Castillo Armas faced a small revolt from young army cadets. They were unhappy that the army had given up. The revolt was stopped, but 29 people died and 91 were injured. Elections were held in early October, and all political parties were banned from taking part. Castillo Armas was the only candidate. He won the election with 99 percent of the votes, completing his move into power.

Castillo Armas became linked with a party called the Movimiento de Liberación Nacional (MLN). This party remained in power in Guatemala from 1954 to 1957. It was led by Mario Sandoval Alarcón and was a group of local politicians, government workers, coffee farmers, and military members. All of them were against the changes made during the Guatemalan Revolution. In the elections for Congress held under Castillo Armas in late 1955, the MLN was the only party allowed to run.

Strict Rule

Before the 1954 coup, Castillo Armas had not talked much about how he would lead the country. He had never clearly stated his beliefs, which worried his CIA contacts. The closest he came was a statement called the "Plan de Tegucigalpa" on December 23, 1953, which criticized the "Sovietization of Guatemala." Castillo Armas had shown support for justicialismo, a political idea from Argentina's President Juan Perón.

Once in power, Castillo Armas worried that he did not have enough public support, so he tried to remove all opposition. He quickly arrested thousands of opposition leaders, calling them communists. Detention camps were built because the jails became too full. Historians believe that more than 3,000 people were arrested after the coup. About 1,000 farm workers were killed by Castillo Armas's troops in one area alone, near Tiquisate.

Following advice from Dulles, Castillo Armas also stopped many citizens from leaving the country. He created a National Committee of Defense Against Communism (CDNCC) with wide powers to arrest, hold, and deport people. Over the next few years, this committee investigated almost 70,000 people. Many were imprisoned, executed, or simply "disappeared," often without a trial.

In August 1954, the government passed a law called Decree 59. This law allowed security forces to hold anyone on the CDNCC's blacklist for six months without a trial. The final list of suspected communists included one out of every ten adults in the country. Efforts were also made to remove people from government jobs who had gotten them under Árbenz. All political parties, labor unions, and farmer groups were made illegal. In historical accounts, Castillo Armas has been called a dictator.

Castillo Armas's government received support from people in Guatemala who had previously supported Ubico. José Bernabé Linares, the very unpopular head of Ubico's secret police, was named the new head of security forces. Linares was known for using torture methods on prisoners. Castillo Armas also took away the right to vote from all people who could not read or write, which was two-thirds of the country's population. He also canceled the 1945 constitution, giving himself almost unlimited power. His government started a strong campaign against trade union members. In 1956, Castillo Armas put a new constitution in place and declared himself president for four years.

His presidency faced opposition from the start. Farm workers continued to fight Castillo Armas's forces until August 1954. There were many uprisings against him, especially in areas that had seen major land reforms.

Reversing Land Reforms

Castillo Armas's government also tried to undo the land reform project started by Árbenz. Large areas of land were taken from the farm workers who had received them under Árbenz and given back to big landowners. Only in a few rare cases were peasants able to keep their lands. Castillo Armas's reversal of Árbenz's land reforms led the US embassy to say it was a "long step backwards" from the previous policy. Thousands of peasants who tried to stay on the lands they had received from Árbenz were arrested by the Guatemalan police. Some peasants were arrested because they were thought to be communists, even though very few of them were. Few of these arrested peasants were ever found guilty, but landowners used the arrests to force peasants off their land.

The government under Castillo Armas issued two new rules about farming policy. In theory, these rules promised to protect the land given out by the Árbenz government under Decree 900. The rules also allowed landowners to ask for the return of land taken "illegally." However, the harsh atmosphere at the time meant that very few peasants could use these rules to their benefit. In total, out of the 529,939 manzanas (about 1.7 acres each) of land taken under Decree 900, 368,481 were taken from peasants and returned to landowners. Ultimately, Castillo Armas did not fully restore the power and privileges of the wealthy and business owners as much as they would have liked. A "liberation tax" he put in place was not popular among the rich.

Economic Challenges

Castillo Armas relied heavily on the military officers and fighters who helped him gain power. This led to widespread corruption, and the US government soon began giving the Guatemalan government millions of dollars. Guatemala quickly became completely dependent on financial support from the Eisenhower government. Castillo Armas could not attract enough business investment. In September 1954, he asked the US for $260 million in aid.

Castillo Armas also directed his government to support a CIA operation called "PBHistory." This was an unsuccessful effort to use documents captured after the 1954 coup to make international opinion favor the US. Despite looking through hundreds of thousands of documents, this operation found no evidence that the Soviet Union was controlling communists within Guatemala. Castillo Armas also found himself too dependent on a group of economic interests, including the cotton and sugar industries in Guatemala and real estate, timber, and oil interests in the US. This made it hard for him to seriously pursue reforms he had promised, such as free trade with the US.

By April 1955, the government's foreign money reserves had dropped from $42 million at the end of 1954 to just $3.4 million. The government faced difficulties borrowing money, leading to money leaving the country. The government also received criticism for black markets and other signs of nearing bankruptcy. By the end of 1954, the number of unemployed people in the country had risen to 20,000, which was four times higher than during the last years of the Árbenz government. In April 1955, the Eisenhower government approved an aid package of $53 million and began to help pay off the Guatemalan government's debt.

Although US government officials complained about Castillo Armas's lack of skill and corruption, he was also praised in the US for acting against communists, and his human rights violations were generally not mentioned. In 1955, during a corn shortage, Castillo Armas gave corn import licenses to some of his old fighters in exchange for a $25,000 bribe. The imported corn, when checked by the United Nations, was found to be unsafe to eat. When a student newspaper revealed the story, Castillo Armas started a police crackdown against those criticizing him. Castillo Armas returned some of the special rights that the United Fruit Company had under Ubico. However, the company did not benefit much from them; it slowly declined due to problems with farming, falling demand, and legal action against it.

Death and Lasting Impact

On July 26, 1957, Castillo Armas was shot and killed by a leftist in the presidential palace in Guatemala City. The killer, Romeo Vásquez Sánchez, was a member of the presidential guard. He approached Castillo Armas as he was walking with his wife and shot him twice. It is not clear if Vásquez acted alone or was part of a larger plan.

Elections were held after Castillo Armas's death. Miguel Ortiz Passarelli, who was aligned with the government, won most of the votes. However, supporters of Miguel Ydígoras Fuentes, another candidate, protested. After this, the army took power and canceled the election results. Another election was held, which Ydígoras Fuentes won easily. Soon after, he declared a "state of siege" and took complete control of the government.

Historians say that by overthrowing Árbenz, the CIA actually made it harder to achieve its goal of a stable Guatemalan government. Historian Stephen Streeter stated that while the US reached some goals by putting Castillo Armas in power, it did so at the cost of Guatemala's democratic system. He also notes that even if Castillo Armas would have committed human rights violations anyway, the US State Department certainly helped and supported these actions.

The reversal of the fair policies of the previous civilian governments led to a series of leftist revolts in the countryside starting in 1960. This sparked the Guatemalan Civil War between the US-backed military government of Guatemala and leftist rebels. The conflict, which lasted from 1960 to 1996, resulted in the deaths of 200,000 civilians. While both sides committed crimes against civilians, 93 percent of these terrible acts were committed by the US-backed military. These included a genocidal "scorched-earth" campaign against the native Maya population during the 1980s. Historians have linked the violence of the civil war to the 1954 coup and the intense "anti-communist paranoia" it created.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Carlos Castillo Armas para niños

In Spanish: Carlos Castillo Armas para niños