Benjamin Constant facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Benjamin Constant

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Member of the Chamber of Deputies | |

| In office 14 April 1819 – 8 December 1830 |

|

| Constituency | Sarthe (1819–24) Seine 4th (1824–27) Bas-Rhin 1st (1827–30) |

| Member of the Council of State | |

| In office 20 April 1815 – 8 July 1815 |

|

| Appointed by | Napoleon I |

| Member of the Tribunat | |

| In office 25 December 1799 – 27 March 1802 |

|

| Constituency | Léman |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Henri-Benjamin Constant de Rebecque

25 October 1767 Lausanne, Swiss Confederacy |

| Died | 8 December 1830 (aged 63) Paris, France |

| Nationality | Swiss and French |

| Political party | Republican (1799–1802) Liberal left (1819–24) Liberal-Doctrinaire (1824–30) |

| Alma mater | University of Edinburgh University of Erlangen |

| Profession |

|

| Writing career | |

| Period | 18th and 19th centuries |

| Genre | Prose, essays, pamphlets |

| Subject | Political theory, liberalism, religion, romantic love |

| Literary movement | Romanticism, classical liberalism |

| Years active | 1792–1830 |

| Notable works |

|

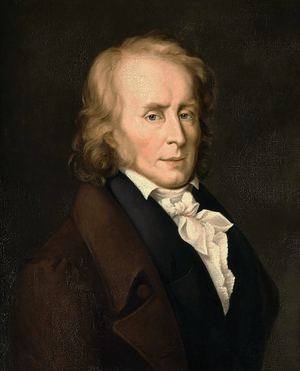

Henri-Benjamin Constant de Rebecque (born October 25, 1767 – died December 8, 1830), often called Benjamin Constant, was an important Swiss-French thinker, activist, and writer. He wrote about politics and religion.

Constant was a strong supporter of a republic (a country governed by elected representatives) from 1795. He supported the changes in government in France in 1797 and 1799. During the time of the French Consulate, he became a leader of the Liberal Opposition in 1800. He disagreed with Napoleon and left France for a while. However, he later supported Napoleon during the Hundred Days and became active in politics again. He was elected as a member of the Chamber of Deputies of France in 1818 and served until his death in 1830. As a leader of the Liberal opposition, he was known for his excellent speeches. He supported a parliamentary system, where the government is accountable to the parliament. During the July Revolution in 1830, he supported Louis Philippe I becoming king.

Besides his many writings on politics and religion, Constant also wrote about romantic feelings. His book Le Cahier rouge (1807) tells about his relationship with Madame de Staël. He worked closely with her, especially in the Coppet group, a famous intellectual circle. He also wrote a successful short novel called Adolphe (1816).

He was a key figure in classical liberalism in the early 1800s. He believed that liberty meant individuals could live their lives without too much interference from the government or society. His ideas influenced many movements for freedom in countries like Spain, Portugal, Greece, Poland, Belgium, Brazil, and Mexico.

Contents

Biography

Early Life and Education

Henri-Benjamin Constant was born in Lausanne, Switzerland. His family were French Huguenot Protestants who had moved to Switzerland to escape religious wars in France. His father, Jules Constant de Rebecque, was a high-ranking officer in the Dutch army. Benjamin's mother died soon after he was born, so his grandmothers raised him.

He was taught by private tutors in Brussels and the Netherlands. He later studied at the University of Erlangen and the University of Edinburgh. While at Erlangen, he had to leave after a personal issue. In Edinburgh, he became friends with James Mackintosh.

Travels and Early Relationships

In 1787, Constant traveled through Scotland and England before returning to Europe. During these years, he was influenced by the ideas of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who believed in equality.

In Paris, he met Isabelle de Charrière, a Dutch writer who was 46 years old. She became a mentor to him. They even wrote a novel together where the story is told through letters. Constant then moved to work at the court of Charles William Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel. He left the court in 1792 when a war began.

In Braunschweig, he married Wilhelmina von Cramm, but their marriage ended in 1793. In 1794, he met Germaine de Staël, a famous and wealthy writer. They admired each other and worked together intellectually from 1795 to 1811. They became one of the most well-known intellectual couples of their time.

Life in Paris and Exile

After a very violent period in France called the Reign of Terror (1793–1794), Constant supported having two parts to the government, like the Parliament of Great Britain. In 1799, Napoleon Bonaparte appointed Constant to a government body called the Tribunat. However, Napoleon soon forced Constant to leave in 1802 because of his speeches and his close connection with Madame de Staël.

In 1803, Madame de Staël was forced to leave Paris. She and Constant traveled to Germany, visiting places like Weimar and Berlin, where they met famous writers like Friedrich Schiller and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Constant later left de Staël and began writing his novel Adolphe. In 1808, he married Caroline von Hardenberg.

He returned to Paris in 1814 when the French monarchy was restored, and Louis XVIII of France became king. Constant suggested a constitutional monarchy, where a king shares power with an elected government. He became friends with Madame Récamier. During Napoleon's brief return to power (the Hundred Days), Constant worked with Napoleon to create changes for a new constitution.

Later Political Career and Death

After Napoleon's final defeat in 1815, Constant moved to London. In 1817, he returned to Paris and was elected to the Chamber of Deputies of France. He became a leader of the "liberals" and was known as one of the best speakers in the Chamber. He opposed King Charles X of France during this period.

In 1822, the famous German writer Goethe praised Constant, saying he had noble goals and always followed the path he chose.

In 1830, King Louis Philippe I helped Constant with his financial difficulties and appointed him to the Conseil d'Etat. Benjamin Constant died in Paris on December 8, 1830, and was buried in the Père Lachaise Cemetery.

Political Philosophy

Ancient and Modern Freedom

Benjamin Constant was one of the first thinkers to call himself a "liberal." He looked to Britain, not ancient Rome, to understand how freedom could work in a large trading society. He explained the difference between the "Liberty of the Ancients" and the "Liberty of the Moderns."

- The Liberty of the Ancients meant citizens could directly influence politics. They would debate and vote in public meetings. This required a lot of time and effort, often with slaves doing most of the work. This type of freedom worked best in small, similar societies.

- The Liberty of the Moderns was about individual rights and freedoms, like the right to speak freely and be safe from too much government control. Direct participation in government would be limited because modern countries are large and most people need to work for a living. Instead, citizens would elect representatives to make decisions for them.

Critique of the French Revolution

Constant criticized parts of the French Revolution. He felt that the French tried to use ancient ideas of freedom in a modern country, which didn't work. He believed that freedom meant having a clear line between a person's private life and government interference.

He pointed out that ancient societies were much smaller than modern ones. He argued that in a large country, ordinary people couldn't have a direct role in government, no matter its form. Constant said that people in ancient times found more happiness in public life, while modern people prefer their private lives.

Constant strongly spoke out against despotism (rule by a single person with absolute power). He believed that some writers who influenced the French Revolution confused power with liberty. They supported any way to expand the government's control. He said that these "reformers" created a very strict government in the name of the Republic. He always condemned despotism, saying that true liberty cannot come from absolute power.

He also highlighted the harmful nature of the Reign of Terror, a period of extreme violence during the revolution. Constant understood that revolutionaries became too focused on politics. He noted that even people living quiet lives were not safe during the Reign of Terror. This widespread fear led to the rise of powerful leaders like Napoleon.

Commerce Over War

Constant believed that in the modern world, trade was better than war. He criticized Napoleon's aggressive wars, saying they were not liberal and didn't fit with modern trading societies. Ancient freedom often relied on war, but a country based on modern freedom would prefer to be at peace with other peaceful nations.

Constant thought that to save liberty after the Revolution, the old idea of ancient freedom needed to be combined with the practical idea of modern freedom. England, after its Glorious Revolution of 1688, showed how modern freedom could work with a constitutional monarchy. Constant concluded that a constitutional monarchy was better than a republic for keeping modern liberty.

He helped write the "Acte Additional" in 1815, which tried to make Napoleon's rule a modern constitutional monarchy. This only lasted for "One Hundred Days," but Constant's work helped combine monarchy with liberty. The French Constitution of 1830 later used many of Constant's ideas. This included a king who inherited his position, along with an elected Chamber of Deputies and a Chamber of Peers. The government's power was given to ministers who were responsible to the parliament.

Constitutional Monarchy

Constant also developed a new idea for a constitutional monarchy. In his view, the king's power should be a neutral power. This neutral power would protect, balance, and limit the other parts of the government: the executive (ministers), the legislature (lawmakers), and the judiciary (courts).

This idea was different from earlier beliefs where the king was seen as the head of the executive branch. In Constant's plan, the executive power would be given to a group of ministers. The king would appoint them, but they would be responsible to Parliament. This clear separation meant that the ministers, not the king, were in charge of governing and making policies. The king would still have important powers, like appointing judges, dissolving the Chamber, and appointing peers, but he would not directly rule. This idea was very important for the development of parliamentary government in France and other countries.

Constant believed in the separation of powers for a free state. But unlike most thinkers who suggested three powers, he proposed five:

- The Monarch or Moderator: A king or emperor who acts as a neutral judge, separate from the government.

- The Executive: The ministers appointed by the monarch, who lead the government.

- The Representative Power of Opinion: An elected group that represents the public's views.

- The Representative Power of Tradition: A hereditary group, like a House of Peers.

- The Judiciary: The court system, similar to other thinkers' ideas.

Constant also supported a "new type of federalism." This was an effort to give more power to local elected councils in France, moving away from a very centralized government. This idea was put into practice in 1831 when elected municipal councils were created.

Comparative Religion

Constant spent forty years studying religion and religious feelings. He wanted to understand this part of human nature, which he saw as a search for improvement. He believed that religious feelings need to adapt and change over time.

Constant strongly felt that the government should not interfere with people's religious beliefs. He thought that each person should decide where to find comfort, moral guidance, or faith. Outside authorities cannot force beliefs; they can only affect people's interests. He also criticized any religion that was only used for practical purposes, as he felt this lowered the value of true religious feeling.

He believed that polytheism (belief in many gods) naturally declined as humans progressed in their understanding. The more humans learn, the more positive effects theism (belief in one God) has. He argued that Christianity, especially Protestantism, was the most accepting form of religion and showed intellectual, moral, and spiritual growth.

Novels

Constant published only one novel during his life, Adolphe (1816). It tells the story of a young man who is unsure of himself and has a difficult relationship with an older woman named Ellenore. The book is told from the young man's point of view and explores his thoughts as he falls in and out of love. The story is thought to be based on Constant's own experiences.

As a young man, Constant also worked with Isabelle de Charrière, a Dutch writer. Together, they wrote a novel told through letters, called Les Lettres d'Arsillé fils, Sophie Durfé et autres.

Legacy

Constant's writings on ancient and modern liberty, and his criticisms of the French Revolution, are very important for understanding his work. The British philosopher Isaiah Berlin said that Constant's ideas greatly influenced him.

Constant's other writings, including his novel Adolphe and his long history of comparative religion, showed the importance of self-sacrifice and human emotions for living in society. While he argued for individual liberty as vital for personal growth and modern life, he believed that being selfish was not part of true individual liberty. He felt that genuine emotions and caring for others were crucial. In this way, his moral and religious ideas were greatly influenced by thinkers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Immanuel Kant.

See also

In Spanish: Benjamin Constant de Rebecque para niños

In Spanish: Benjamin Constant de Rebecque para niños