Alexis de Tocqueville facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Alexis de Tocqueville

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait by Théodore Chassériau (1850), at the Palace of Versailles

|

|

| Minister of Foreign Affairs | |

| In office 2 June 1849 – 30 October 1849 |

|

| Prime Minister | Odilon Barrot |

| Preceded by | Édouard Drouyn de Lhuys |

| Succeeded by | Alphonse de Rayneval |

| President of the General Council of Manche | |

| In office 27 August 1849 – 29 April 1852 |

|

| Preceded by | Léonor-Joseph Havin |

| Succeeded by | Urbain Le Verrier |

| Member of the National Assembly for Manche |

|

| In office 25 April 1848 – 3 December 1851 |

|

| Preceded by | Léonor-Joseph Havin |

| Succeeded by | Hervé de Kergorlay |

| Constituency | Sainte-Mère-Église |

| Member of the Chamber of Deputies for Manche |

|

| In office 7 March 1839 – 23 April 1848 |

|

| Preceded by | Jules Polydore Le Marois |

| Succeeded by | Gabriel-Joseph Laumondais |

| Constituency | Valognes |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Alexis Charles Henri Clérel de Tocqueville

29 July 1805 Paris, France |

| Died | 16 April 1859 (aged 53) Cannes, France |

| Resting place | Tocqueville, Manche |

| Political party | Movement Party (1839–1848) Party of Order (1848–1851) |

| Spouse |

Mary Mottley

(m. 1835) |

| Alma mater | University of Paris |

| Profession | Historian, magistrate, jurist |

|

Philosophy career |

|

|

Notable work

|

Democracy in America (1835) The Old Regime and the Revolution (1856) |

| Era | 19th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Liberalism Liberal conservatism |

|

Main interests

|

History, political philosophy, sociology |

|

Notable ideas

|

Voluntary association, mutual liberty, soft despotism, soft tyranny, Tocqueville effect |

|

Influences

|

|

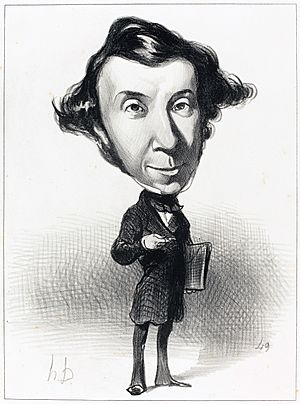

Alexis Charles Henri Clérel, comte de Tocqueville (French: [a.lɛk.si‿də tɔk.vil]; born July 29, 1805 – died April 16, 1859), often called Tocqueville (/ˈtɒkvɪl, ˈt[unsupported input]-/), was a French writer, diplomat, and historian. He is famous for his books Democracy in America (published in 1835 and 1840) and The Old Regime and the Revolution (1856).

In these books, he looked closely at how people lived and interacted in Western societies. He also studied their connection to the economy and the government. Democracy in America came out after Tocqueville traveled through the United States. Today, it is seen as an important early work in the fields of sociology and political science.

Tocqueville was involved in French politics. He served first during the July Monarchy (1830–1848) and then in the Second Republic (1849–1851). He stopped his political work after Louis Napoléon Bonaparte's coup in December 1851. After that, he started writing The Old Regime and the Revolution.

Tocqueville believed the French Revolution continued France's efforts to modernize and centralize its government. This process had started under King Louis XIV. He thought the Revolution failed because its leaders were new to politics. They were too focused on abstract ideas from the Age of Enlightenment.

Tocqueville was a classical liberal. This means he supported parliamentary government, where elected representatives make laws. He was also careful about the extreme sides of democracy. In parliament, he was part of the centre-left group. His ideas about freedom were complex, so people from different political views have found inspiration in his writings.

Contents

Alexis de Tocqueville's Life

Tocqueville came from a very old and important family in Paris. His great-grandfather, Malesherbes, was a statesman who was executed in 1794. His parents, Hervé Louis François Jean Bonaventure Clérel and Louise Madeleine Le Peletier de Rosanbo, barely escaped the same fate in 1794. This happened when Maximilien de Robespierre lost power.

Under the Bourbon Restoration, Tocqueville's father became a noble and a high-ranking official. Tocqueville went to the Lycée Fabert school in Metz.

Tocqueville did not like the July Monarchy (1830–1848). He started his political career in 1839. From 1839 to 1851, he was a member of the lower house of parliament. He represented the Manche region.

He was part of the centre-left group. He supported ending slavery and believed in free trade. He also supported France's colonization of Algeria.

In 1842, he became a member of the American Philosophical Society. In 1847, he tried to start a "Young Left" political party. This party would have pushed for higher wages and a progressive tax. These ideas aimed to reduce the appeal of socialist movements.

Tocqueville was also elected as a general counselor for Manche in 1842. He became the president of the department's general council from 1849 to 1852. He later resigned because he refused to support the Second Empire. Some say his political position became difficult. He was not fully trusted by either the left or the right.

Travels and Observations

In 1831, Tocqueville received permission from the July Monarchy to study prisons in the United States. He traveled there with his friend Gustave de Beaumont. While he did visit some prisons, Tocqueville explored much of the United States. He took many notes on what he saw and thought.

He returned after nine months and published a report. But the most important result of his trip was De la démocratie en Amérique, which came out in 1835. Beaumont also wrote about their travels in Jacksonian America: Marie or Slavery in the United States (1835). During this journey, Tocqueville also visited Montreal and Quebec City in Lower Canada in late 1831.

Besides North America, Tocqueville also visited England. There, he wrote about poverty in his Memoir on Pauperism. In 1841 and 1846, he traveled to the French colony of Algeria. His first trip led to his work Travail sur l'Algérie. In this work, he criticized France's approach to colonization. France tried to make Algerians adopt Western culture.

Tocqueville suggested that the French government use a form of indirect rule. This meant not mixing different populations together. He even suggested racial segregation with separate laws for European colonists and Arabs. This idea was put into practice later with the 1881 Indigenous code.

In 1835, Tocqueville traveled through Ireland. His observations give us a good picture of Ireland before the Great Famine (1845–1849). He wrote about the growing Catholic middle class. He also described the terrible living conditions of most Catholic tenant farmers. Tocqueville clearly showed his dislike for aristocratic power. He also showed his support for his fellow Catholics in Ireland.

After the French Revolution of 1848, Tocqueville was elected to the Constituent Assembly of 1848. He joined the group tasked with writing the new Constitution for the Second Republic. He supported a two-house parliament and electing the President by universal suffrage. He thought universal suffrage would help balance the revolutionary spirit in Paris.

During the Second Republic, Tocqueville sided with the Party of Order against the socialists. After the February 1848 uprising, he predicted a violent conflict. He saw a clash coming between Parisian workers, led by socialists, and conservatives. These social tensions exploded in the June Days Uprising of 1848.

Tocqueville supported the suppression of the uprising by General Cavaignac. He approved measures that suspended the normal constitutional order. Between May and September, Tocqueville helped write the new Constitution. His ideas, like his amendment about the President, came from his experiences in North America.

Minister of Foreign Affairs

Tocqueville supported Cavaignac and the Party of Order. He became Minister of Foreign Affairs in Odilon Barrot's government. This was from June 3 to October 31, 1849. During the difficult days of June 1849, he urged the Interior Minister to declare a state of emergency in Paris. He also approved arresting demonstrators.

Tocqueville had supported laws limiting political freedoms since February 1848. He approved two laws passed after June 1849. These laws limited the freedom of clubs and the freedom of the press. This support for limiting freedoms seems different from his defense of freedoms in Democracy in America.

Tocqueville believed that order was essential for good politics. He hoped to bring stability to French political life. This stability would allow freedom to grow without constant revolutionary changes.

Tocqueville had supported Cavaignac over Louis Napoléon Bonaparte in the 1848 presidential election. He opposed Louis Napoléon Bonaparte's coup on December 2, 1851. Tocqueville was among the deputies who tried to resist the coup. They tried to have Napoleon III charged with "high treason" for breaking the law about term limits.

Tocqueville was detained and then released. He supported bringing back the Bourbons instead of Napoleon III's Second Empire (1851–1871). He left political life and went to his castle (Château de Tocqueville).

Tocqueville could not bring himself to serve a leader he saw as a dictator. He fought for political liberty, which he strongly believed in. He spent 13 years of his life in politics. He would continue this fight from his home, using libraries and archives. There, he started writing L'Ancien Régime et la Révolution. He published the first part in 1856, but the second part was unfinished.

Death

Tocqueville suffered from tuberculosis for a long time. He died from the disease on April 16, 1859. He was buried in the Tocqueville cemetery in Normandy.

Tocqueville was a Roman Catholic. He believed that religion could exist well with both equality and individualism. He felt that religion would be strongest when it was separate from politics.

Democracy in America

In Democracy in America, published in 1835, Tocqueville wrote about the New World and its growing democracy. He observed the United States in the early 1800s. At that time, big changes like the Market Revolution and Jacksonian democracy were shaping American life.

The main goal of the book was not just to describe American democracy. It was also to show that democracy is a result of industrialization. Tocqueville suggested that history is shaped by how societies develop their economies.

According to political scientist Joshua Kaplan, one reason for writing Democracy in America was to help the French people. He wanted them to understand their own situation. France was moving from an old aristocratic system to a new democratic one. Tocqueville saw democracy as a balance between liberty and equality. It was about caring for both the individual and the community.

Tocqueville strongly supported liberty. He wrote: "I have a passionate love for liberty, law, and respect for rights." He added: "Liberty is my foremost passion." He also wrote about a "depraved taste for equality." This taste makes weak people want to bring strong people down to their level. It makes people prefer equality even if it means being enslaved, rather than having freedom with some inequality.

His view on government showed his belief in liberty. He felt individuals needed to act freely while respecting others' rights. About centralized government, he wrote that it "excels in preventing, not doing."

Tocqueville also commented on equality: "When citizens are all almost equal, it becomes difficult for them to defend their independence against powerful forces. Since no one is strong enough to fight alone, the only way to guarantee liberty is for everyone to combine forces. But such a combination is not always easy to see."

Tocqueville said that inequality can motivate the poor to become rich. He noted that wealth often changes hands over generations. Inheritance laws that divide estates cause a constant cycle. This cycle can make the poor rich and the rich poor over time. He compared this to France, where laws protected estates from being divided. This preserved wealth and prevented the churn seen in the United States.

On Society and the Individual

Tocqueville wanted to understand how political society worked. He also looked at different types of political groups. He thought about civil society too, and how it connected to political society. For Tocqueville, civil society was about private businesses and everyday life, guided by laws.

Tocqueville was concerned about individualism. He believed that Americans could overcome selfish desires by working together. This cooperation, in both public and private life, created a strong political society and a lively civil society.

According to political scientist Joshua Kaplan, Tocqueville changed the meaning of individualism. He saw it as a "calm and considered feeling." This feeling makes people want to focus on their family and friends. They then "gladly leaves the greater society to look for itself." Tocqueville saw egotism and selfishness as bad traits. But he saw individualism as a way of thinking that could have good or bad results.

When individualism led people to work together for common goals, it was positive. It was seen as "self-interest properly understood." This helped balance the danger of the tyranny of the majority. People could "take control over their own lives" without government help. Kaplan says Americans find it hard to accept Tocqueville's criticism. He felt the "omnipotence of the majority" limited independent thinking.

Others, like Catholic writer Daniel Schwindt, disagree. They argue that Tocqueville saw individualism as just another form of egotism.

On Democracy and New Forms of Tyranny

Tocqueville warned that modern democracy might create new types of tyranny. He thought that extreme equality could lead to people caring only about money. This could also lead to the selfishness of individualism. James Wood of The New Yorker wrote that we might become so focused on "present enjoyments." This could make us lose interest in the future. We might then allow a powerful, hidden force to lead us.

Tocqueville worried that if despotism (absolute rule) took hold in a democracy, it would be very dangerous. Past tyrants could only affect a small group of people. But a democratic despotism could control "a multitude of men." These men would be alike, equal, and always seeking small pleasures. They would be unaware of others and controlled by a powerful state.

Tocqueville compared a possibly despotic democratic government to a protective parent. This parent wants to keep its citizens (children) as "perpetual children." It does not break their will, but guides it. It watches over people like a shepherd caring for a "flock of timid animals."

On the American Social Contract

Tocqueville tried to understand what made American political life special. He agreed with thinkers like Aristotle and Montesquieu. They believed that how property was owned affected political power. But his conclusions were very different from theirs. Tocqueville wanted to know why the United States was so different from Europe. Europe was still dealing with the last parts of its aristocratic system.

In contrast to Europe's noble traditions, the United States valued hard work and making money. Ordinary people had a level of respect that was new. Common people did not look up to elites. What he called strong individualism and market capitalism had taken deep root.

Tocqueville wrote: "Among a democratic people, where there is no hereditary wealth, every man works to earn a living. [...] Labor is held in honor; the prejudice is not against but in its favor." He said that the values that won in the North, and were also in the South, were starting to replace old European ways. Laws ended primogeniture (eldest son inheriting everything) and entails (keeping land in the family). This led to land being owned by more people.

This was different from the old aristocratic pattern. In that system, only the eldest child, usually a man, inherited the estate. This kept large estates together for generations. In the United States, wealthy families were less likely to pass everything to one child. This meant that over time, large estates were divided among heirs. This made children more equal overall.

According to Joshua Kaplan's view of Tocqueville, this was not always a bad thing. Family bonds and shared experiences often replaced the formal relationship between the eldest child and siblings. This was common in the old aristocratic system. Overall, it became very hard to keep inherited wealth in new democracies. More people had to work for their own living.

Tocqueville understood that this rapidly democratizing society had people who valued "middling" things. They wanted to earn large fortunes through hard work. He believed this explained why the United States was so different from Europe. In Europe, he claimed, no one cared much about making money. The lower classes had little hope of getting rich. The upper classes thought it was rude to care about money, and many already had wealth guaranteed.

But in the United States, workers would see people in fancy clothes. They would simply say that with hard work, they too would soon be rich enough for such luxuries. Tocqueville believed that even though property ownership affected power, the United States showed that fair property distribution did not guarantee the best leaders. In fact, it did the opposite. The widespread, fair property ownership in the U.S. also explained why Americans disliked elites so much.

On Majority Rule and Mediocrity

Beyond getting rid of old aristocracy, ordinary Americans also refused to respect those with superior talent and intelligence. As a result, these natural leaders could not gain much political power. Ordinary Americans had too much power and spoke too loudly in public. They would not listen to intellectual superiors.

This culture promoted a strong sense of equality, Tocqueville argued. But the same customs and opinions that ensured equality also encouraged mediocrity. Those with true virtue and talent had limited choices.

Tocqueville said that educated and intelligent people had two options. They could join small intellectual groups to discuss society's complex problems. Or, they could use their talents to get rich in the private sector. He wrote that he did not know any country where there was "less independence of mind, and true freedom of discussion, than in America."

Tocqueville blamed the power of majority rule for stifling thinking. He said: "The majority has enclosed thought within a formidable fence. A writer is free inside that area, but woe to the man who goes beyond it. He does not fear an inquisition, but he must face all kinds of unpleasantness in everyday persecution. A career in politics is closed to him, for he has offended the only power that holds the keys."

According to Kaplan's view of Tocqueville, a serious problem in politics was not that people were too strong. Instead, people were "too weak" and felt powerless. The danger was that people felt "swept up in something that they could not control."

On Slavery, Black People, and Native Americans

Tocqueville's Democracy in America was written at a key moment in American history. It tried to capture the true nature of American culture and values. Even though he supported colonialism, Tocqueville clearly saw the wrongs done to black people and Native Americans in the United States.

Tocqueville dedicated the last chapter of the first volume of Democracy in America to this issue. His travel companion, Gustave de Beaumont, focused entirely on slavery in his book Marie or Slavery in America.

On Policies of Assimilation

Tocqueville believed that it would be almost impossible for black people to fully join American society. He saw this already happening in the Northern states. As Tocqueville predicted, after the Civil War and during Reconstruction, black people would have formal freedom and equality, but also segregation. The path to true integration would be difficult.

However, Tocqueville thought that joining American society was the best solution for Native Americans. But he felt they were too proud to do so. He believed they would eventually disappear. Forcing people to move was another part of America's Indian policy. Tocqueville believed both groups lacked the qualities needed to live in a democracy. Tocqueville shared many common views of his time on assimilation and segregation. However, he disagreed with Arthur de Gobineau's theories in The Inequality of Human Races (1853–1855).

On the United States and Russia as Future Global Powers

In Democracy in America, Tocqueville also predicted that the United States and Russia would become the two main global powers. He wrote: "There are now two great nations in the world, which starting from different points, seem to be advancing toward the same goal: the Russians and the Anglo-Americans. [...] Each seems called by some secret design of Providence one day to hold in its hands the destinies of half the world."

On Civil Jury Service

Tocqueville believed that the American jury system was very important. It helped teach citizens about self-government and the rule of law. He often said that the civil jury system was one of the best examples of democracy. It connected citizens with the true spirit of justice.

In his 1835 book Democracy in America, he explained: "The jury, and more especially the civil jury, helps spread the spirit of judges to all citizens. This spirit, with the habits it brings, is the best preparation for free institutions. [...] It gives each citizen a kind of official role. It makes them all feel the duties they must perform for society. It also shows them the part they play in the Government."

Tocqueville believed that jury service benefited society as a whole. It also improved jurors' qualities as citizens. Because of the jury system, "they learned more about the rule of law. They also felt more connected to the state. So, besides helping resolve disputes, serving on a jury had good effects on the jurors themselves."

Views on the Conquest of Algeria

The French historian of colonialism, Olivier LeCour Grandmaison, pointed out how Tocqueville used the word "extermination". He used it to describe what happened during the colonization of the Western United States and the Indian removal period. Tocqueville wrote in an 1841 essay about the conquest of Algeria:

As far as I am concerned, I came back from Africa with the pathetic notion that at present in our way of waging war we are far more barbaric than the Arabs themselves. These days, they represent civilization, we do not. This way of waging war seems to me as stupid as it is cruel. It can only be found in the head of a coarse and brutal soldier. Indeed, it was pointless to replace the Turks only to reproduce what the world rightly found so hateful in them. This, even for the sake of interest is more noxious than useful; for, as another officer was telling me, if our sole aim is to equal the Turks, in fact we shall be in a far lower position than theirs: barbarians for barbarians, the Turks will always outdo us because they are Muslim barbarians. In France, I have often heard men I respect, but do not approve of, deplore that crops should be burnt and granaries emptied and finally that unarmed men, women, and children should be seized. In my view these are unfortunate circumstances that any people wishing to wage war against the Arabs must accept. I think that all the means available to wreck tribes must be used, barring those that the human kind and the right of nations condemn. I personally believe that the laws of war enable us to ravage the country and that we must do so either by destroying the crops at harvest time or any time by making fast forays, also known as raids, whose aim is to get hold of men or flocks.

Whatever the case, we may say in a general manner that all political freedoms must be suspended in Algeria.

Tocqueville thought the conquest of Algeria was important for two reasons. First, he saw it as important for France's place in the world. Second, he saw it as a way to change French society. Tocqueville believed that war and colonization would "restore national pride." He thought this pride was threatened by the "gradual softening of social customs" among the middle classes. Their desire for "material pleasures" was spreading, giving society "an example of weakness and egotism."

Tocqueville praised the methods of General Bugeaud. He even claimed that "war in Africa is a science." He said everyone knew its rules and could apply them with almost certain success. He felt one of Bugeaud's greatest services was spreading this "new science."

Tocqueville supported racial segregation in Algeria. He wanted two different sets of laws: one for European colonists and one for the Arab population. This two-tier system was later fully put into place. The 1870 Crémieux decree and the Indigenousness Code gave French citizenship to European settlers and Algerian Jews. But Muslim Algerians were governed by Muslim law and had second-class citizenship.

Opposition to the Invasion of Kabylie

Historian Jean-Louis Benoît argued that Tocqueville was one of the "most moderate supporters" of Algerian colonization. This was especially true given the strong racial prejudices of the time. Benoît said it was wrong to assume Tocqueville always supported Bugeaud. It seems Tocqueville changed his views after his second visit to Algeria in 1846. He criticized Bugeaud's plan to invade Kabylie in an 1847 speech.

Tocqueville had favored keeping distinct traditional laws and schools for Arabs under French control. However, he called the Berber tribes of Kabylie "savages" in his 1837 Two Letters on Algeria. He thought they were not suited for this arrangement. He argued they would be better managed by trade and cultural interaction, not by force.

Tocqueville's views were complex. In his 1841 report on Algeria, he praised Bugeaud for defeating Abd-el-Kader's resistance. Yet, in the Two Letters, he had suggested the French military should leave Kabylie alone. In later speeches and writings, he continued to oppose invading Kabylie.

In a debate about extra funds in 1846, Tocqueville criticized Bugeaud's military actions. He successfully convinced the Assembly not to approve funds for Bugeaud's military campaigns. Tocqueville saw Bugeaud's plan to invade Kabylie, despite the Assembly's opposition, as an act of rebellion. He felt the government was being cowardly in response.

1847 "Report on Algeria"

In his 1847 "Report on Algeria", Tocqueville stated that Europe should avoid repeating the mistakes made during the European colonization of the Americas. This was to prevent bloody outcomes. He specifically warned his countrymen that if their methods toward the Algerian people did not change, colonization would end in a bloodbath.

Tocqueville's report on Algeria said that the fate of French soldiers and finances depended on how the French government treated the native populations. This included Arab tribes, independent Kabyles in the Atlas Mountains, and the powerful leader Abd-el-Kader. In his writings on Algeria, Tocqueville discussed different ways a European country could approach imperialism. He distinguished between "dominance" and a specific type of "colonization."

The latter focused on gaining and protecting land and routes that promised commercial wealth. For Algeria, Tocqueville saw the Port of Algiers and control over the Strait of Gibraltar as very valuable. He did not think direct control over all of Algeria's political operations was necessary. So, he emphasized controlling only certain key points for commercial colonization.

Tocqueville argued that even though it was unpleasant, using violence was necessary for colonization. He believed it was justified by the laws of war. He did not explain these laws in detail. However, since France's goal in Algeria was commercial and military gain, not self-defense, his views do not align with just war theory's idea of a just cause. Also, since he approved of destroying civilian homes, his approach does not fit with just war theory's rules for proportionality and discrimination in war.

The Old Regime and the Revolution

In 1856, Tocqueville published The Old Regime and the Revolution. This book looks at French society before the French Revolution. This period is known as the Ancien Régime. The book explores the reasons that led to the Revolution.

Works

- Alexis de Tocqueville and Gustave de Beaumont in America: Their Friendship and Their Travels, edited by Olivier Zunz, translated by Arthur Goldhammer (University of Virginia Press, 2011, ISBN: 9780813930626), 698 pages. Includes previously unpublished letters, essays, and other writings.

- Du système pénitentaire aux États-Unis et de son application en France (1833) – On the Penitentiary System in the United States and Its Application to France, with Gustave de Beaumont.

- De la démocratie en Amérique (1835/1840) – Democracy in America. It was published in two volumes, the first in 1835, the second in 1840. English language versions: Tocqueville, Democracy in America, trans. and eds, Harvey C. Mansfield and Delba Winthrop, University of Chicago Press, 2000; Tocqueville, Democracy in America (Arthur Goldhammer, trans.; Olivier Zunz, ed.) (The Library of America, 2004) ISBN: 9781931082549.

- L'Ancien Régime et la Révolution (1856) – The Old Regime and the Revolution. It is Tocqueville's second most famous work.

- Recollections (1893) – This work was a private journal of the Revolution of 1848. He never intended to publish this during his lifetime; it was published by his wife and his friend Gustave de Beaumont after his death.

- Journey to America (1831–1832) – Alexis de Tocqueville's travel diary of his visit to America; translated into English by George Lawrence, edited by J.-P. Mayer, Yale University Press, 1960; based on vol. V, 1 of the Œuvres Complètes of Tocqueville.

- L'État social et politique de la France avant et depuis 1789 – Alexis de Tocqueville

- Memoir on Pauperism: Does public charity produce an idle and dependant class of society? (1835) originally published by Ivan R. Dee. Inspired by a trip to England. One of Tocqueville's more obscure works.

- Journeys to England and Ireland, 1835.

See Also

In Spanish: Alexis de Tocqueville para niños

In Spanish: Alexis de Tocqueville para niños

- The Alexis de Tocqueville Tour: Exploring Democracy in America

- Alexis de Tocqueville Institution

- Benjamin Constant, author of Liberty of the Ancients and the Moderns

- Gustave de Beaumont, Tocqueville's best friend and travel companion to the United States

- Ferdinand de Lesseps, French diplomat and developer of Suez Canal

- Prix Alexis de Tocqueville

- Tocqueville effect, a social phenomenon

- Civil society

- Contributions to liberal theory

- Liberalism

- List of historians of the French Revolution

- Soft despotism

- Tyranny of the majority

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |