Leo Strauss facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

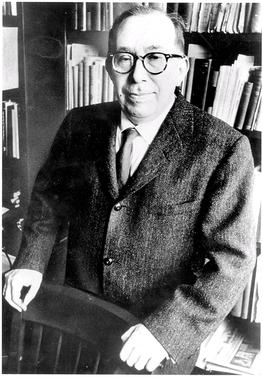

Leo Strauss

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | September 20, 1899 |

| Died | October 18, 1973 (aged 74) |

| Alma mater | University of Marburg University of Hamburg University of Freiburg Columbia University |

|

Notable work

|

|

| Spouse(s) | Miriam Bernsohn Strauss |

| Awards | Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School |

|

| Institutions | Higher Institute for Jewish Studies Columbia University University of Cambridge The New School Hamilton College University of Chicago Claremont McKenna College St. John's College |

| Thesis | Das Erkenntnisproblem in der philosophischen Lehre Fr. H. Jacobis (On the Problem of Knowledge in the Philosophical Doctrine of F. H. Jacobi) (1921) |

| Doctoral advisor | Ernst Cassirer |

|

Main interests

|

|

|

Notable ideas

|

Noetic heterogeneity The ends of politics and philosophy as irreducible to one another The unresolvable tension between reason and revelation Criticism of positivism, moral relativism, historicism, and nihilism The distinction between esoteric and exoteric writing Reopening the quarrel of the ancients and the moderns Reductio ad Hitlerum |

|

Influences

|

|

|

Influenced

|

|

Leo Strauss (strowss; September 20, 1899 – October 18, 1973) was a German-American thinker who studied political philosophy. He was born in Germany to Jewish parents. Strauss later moved from Germany to the United States.

He spent a lot of his career as a professor at the University of Chicago. There, he taught many students and wrote fifteen books. Strauss was known for his ideas on how ancient thinkers wrote. He believed they often hid their true meanings in their texts.

Biography

Early Life and Education

Leo Strauss was born on September 20, 1899. This was in a small town called Kirchhain in Germany. His parents were Hugo and Jennie Strauss. He grew up in a Jewish home. Strauss said his family followed Jewish laws strictly.

He went to school in Kirchhain and then to a high school in Marburg. In 1917, he joined the German army during World War I. He served until December 1918.

After the war, Strauss went to the University of Hamburg. He earned his doctorate degree in 1921. His main teacher was Ernst Cassirer. Strauss also took classes at other universities. He learned from famous thinkers like Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger. During this time, he became involved with the German Zionist movement. This led him to meet many important Jewish thinkers.

Academic Career and Moves

In 1932, Strauss received a special scholarship. This allowed him to move to Paris. He only visited Germany once more, many years later. In Paris, he married Marie Bernsohn. He adopted her son, Thomas. Later, he also adopted his sister's child, Jenny.

Because the Nazis came to power, Strauss decided not to return to Germany. He found a temporary job in England at the University of Cambridge. In 1937, he moved to the United States. He worked at The New School in New York City for several years. He became a U.S. citizen in 1944.

In 1949, Strauss became a professor at the University of Chicago. He taught there until 1969. In 1953, he created the phrase reductio ad Hitlerum. This phrase means trying to win an argument by comparing someone's idea to Adolf Hitler's. It suggests this is often a faulty way to argue.

Later, Strauss moved to Claremont McKenna College in California for a year. Then, in 1970, he moved to St. John's College, Annapolis. He taught there until he passed away in 1973. He was buried in Annapolis.

Main Ideas

Philosophy and Politics

For Strauss, politics and philosophy were closely connected. He believed that political philosophy began when Socrates was put on trial and died. Socrates argued that thinkers could not study nature without also thinking about human nature. Humans are "political animals," meaning they live in communities.

However, Strauss also thought that the goals of politics and philosophy were different. They could not be fully combined. Strauss saw himself as a "scholar" rather than a "great thinker." He believed scholars are careful and follow methods. Great thinkers, on the other hand, bravely tackle big problems.

How to Read Old Texts

In the late 1930s, Strauss suggested looking again at the idea of "exoteric" (public) and "esoteric" (secret) writing. In 1952, he wrote a book called Persecution and the Art of Writing. He argued that important writers often wrote with hidden meanings. They might use irony, puzzles, or even seem to contradict themselves.

This "esoteric" writing had several purposes. It could protect the philosopher from rulers who might disagree with their ideas. It also protected society from ideas that might be too shocking. This way of writing also helped attract the right kind of reader. It made readers think deeply to find the hidden message. Strauss learned this idea from studying thinkers like Maimonides and Al-Farabi.

Strauss believed that before the 1800s, people understood that philosophical writing was not always openly accepted by society. Philosophers had to be careful. They had to hide their true thoughts from those in power. This was especially true in medieval times, when thinkers could be punished for their ideas.

Views on Politics and Society

Strauss believed that modern social science was flawed. He thought it wrongly separated facts from values. He traced this idea back to thinkers like Max Weber. Strauss argued that a political scientist who tried to study politics without values was fooling themselves. He felt that positivism, which tries to make value-free judgments, couldn't even explain why it existed without making a value judgment.

Modern liberalism focuses on individual freedom. But Strauss thought there should be more focus on human excellence and good behavior in politics. He often asked how freedom and excellence could exist together.

Debates with Other Thinkers

Strauss had important discussions with two thinkers: Carl Schmitt and Alexandre Kojève. Schmitt was a German legal scholar. Strauss's early work on Thomas Hobbes helped him get funding to leave Germany. Strauss disagreed with Schmitt's idea that humans are naturally evil and need strong rule. Strauss thought we should look back at older ideas about human nature.

Strauss and Kojève were close friends. Kojève believed philosophers should actively shape political events. Strauss, however, thought philosophers should only get involved in politics to make sure philosophy itself could be free. He saw philosophy as the most important human activity.

Liberalism and Its Challenges

Strauss argued that modern liberalism could lead to extreme relativism. This, he believed, could lead to two types of nihilism (the belief that life has no meaning or values).

One type was "brutal" nihilism, seen in Nazi and Bolshevik governments. These groups tried to destroy old traditions and morals. The other type was "gentle" nihilism, found in Western liberal democracies. Strauss saw this as a lack of purpose and a focus on pleasure. He thought it was spreading through American society.

Strauss believed that modern problems like relativism and nihilism were hurting society and philosophy. He suggested looking back at classical political philosophy. This could help us understand how to act politically.

Ancient vs. Modern Ideas

Strauss often highlighted two main differences in political philosophy. The first was between Athens and Jerusalem, representing reason and revelation (religious belief). The second was between "Ancients" and "Moderns." The "Ancients" were thinkers like Socrates and Plato. The "Moderns" started with Niccolò Machiavelli.

The Ancients, like Socrates, brought philosophy back to everyday life and made it more political. The Moderns reacted to the strong influence of religion in medieval times. They promoted the power of reason. Thinkers like Thomas Hobbes focused on basic human fears and hopes. This led to later ideas about politics based on economics.

Strauss and Zionism

When he was young, Strauss was part of a German Zionist youth group. He was a follower of Vladimir Jabotinsky. He wrote about Zionism but stopped these activities in his early twenties.

Later, Strauss still had some interest in Zionism. But he also saw it as "problematic." He taught at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem for a year. He once wrote that political Zionism was "problematic for obvious reasons." But he also said he could never forget how it helped as a "moral force" in a time of change. He saw it as having a "conservative function."

Religious Beliefs

Strauss thought that religious belief could be useful. He did not like atheism, which he saw as extreme and illogical. However, he also believed that religious ideas should be examined using reason. He suggested that the question "What is God?" should always be open to discussion.

Some scholars believe Strauss saw religion only as a tool for society. But others argue that he saw it as deeply connected to the nature of society and authority.

Criticisms of Strauss's Ideas

Views on Society

Some critics say Strauss was elitist. They argue he was against democracy. Journalists have suggested that Strauss supported "noble lies." These are myths that leaders might use to keep society together. In his book The City and Man, Strauss discussed myths needed for governments. These include believing that a country's land truly belongs to it, even if it was taken unfairly.

Some critics, like Shadia Drury, claimed Strauss taught that leaders should always deceive citizens. They say he believed people need strong rulers to tell them what is good. Nicholas Xenos called Strauss "an anti-democrat" and a "true reactionary." Xenos suggested Strauss wanted to return to an older time of "imperial domination" and "authoritarian rule."

Against History

Some conservatives also criticized Strauss. They argued that his ideas created a false separation between universal morals and tradition. They said Strauss wrongly assumed that respecting tradition would weaken reason. Critics like Claes G. Ryn argued that understanding history is important for understanding universal truths. They felt Strauss's ideas about natural rights were too abstract.

Ryn suggested that Strauss's anti-historical thinking connected him to the French Jacobins. The Jacobins also saw tradition as against virtue and reason.

See also

In Spanish: Leo Strauss para niños

In Spanish: Leo Strauss para niños

- American philosophy

- List of American philosophers

- Neoconservatism, often referred as inspired by the work of Strauss

- Lev Shestov

- Allan Bloom

- Seth Benardete

- Jacob Klein

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |