Moses Mendelssohn facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Moses Mendelssohn

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait by Anton Graff (1773)

|

|

| Born | 6 September 1729 Dessau, Anhalt-Dessau

|

| Died | 4 January 1786 (aged 56) |

| Era | 18th-century philosophy |

|

Main interests

|

Metaphysics · Philosophy of religion |

| Signature | |

|

|

Moses Mendelssohn (born September 6, 1729 – died January 4, 1786) was a very important German-Jewish philosopher and theologian. His ideas about Jewish people, their religion, and their identity were key to the Haskalah. This was also known as the 'Jewish Enlightenment' of the 1700s and 1800s.

Mendelssohn was born into a poor Jewish family in Dessau, Principality of Anhalt. He was first expected to become a rabbi. However, he taught himself about German ideas and literature. Through his writings on philosophy and religion, he became a leading thinker of his time. Both Christian and Jewish people in German-speaking Europe respected him. He also worked in the Berlin textile industry, which helped his family become wealthy.

Many famous people are his descendants. These include the composers Fanny and Felix Mendelssohn. Felix's son, the chemist Paul Mendelssohn Bartholdy, is also a descendant. Fanny's grandsons, Paul and Kurt Hensel, are too. His family also founded the Mendelssohn & Co. banking house.

Contents

Life Story of Moses Mendelssohn

Early Life and Education

Moses Mendelssohn was born in Dessau. His father's name was Mendel. Moses and his brother Saul were the first in their family to use the last name Mendelssohn, meaning "Mendel's son."

Moses's father was a poor scribe, who wrote Torah scrolls. Moses had a curved spine from a young age. His father and the local rabbi, David Fränkel, taught him early on. They taught him the Bible and Talmud. Rabbi Fränkel also introduced him to the ideas of Maimonides.

In 1743, Rabbi Fränkel moved to Berlin. A few months later, 14-year-old Moses followed him. He entered Berlin through the Rosenthaler Tor, the only gate Jews were allowed to use. Mendelssohn joined Fränkel's school, where he studied old texts and Jewish law.

He mostly taught himself. A Jewish refugee from Poland, Israel Zamosz, taught him math. A young Jewish physician taught him Latin. He bought a Latin copy of John Locke's An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. He learned it using a Latin dictionary. He also met Aaron Solomon Gumperz, who taught him basic French and English. In 1750, a rich Jewish silk merchant, Isaac Bernhard, hired him to teach his children. Mendelssohn soon became Bernhard's bookkeeper and then his business partner.

Becoming a Famous Thinker

In 1754, Mendelssohn likely met Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, who became one of his best friends. They are said to have played chess when they first met. Lessing's play Nathan the Wise features characters who meet over a chess game. Lessing saw in Mendelssohn the kind of noble Jewish character he wrote about.

Lessing helped Mendelssohn become known to the public. Mendelssohn had written an essay about German philosophers. Lessing published it without his permission in 1755. It was called Philosophical Conversations.

From 1756 to 1759, Mendelssohn became a key figure in important literary projects. In 1762, he married Fromet Guggenheim. She lived 26 years longer than him. The year after his marriage, Mendelssohn won a prize from the Berlin Academy. His essay was about using math in philosophy. Immanuel Kant came in second place. In 1763, the king gave Mendelssohn special permission to live in Berlin.

Mendelssohn then decided to write about the idea of the soul living forever. Many people at the time doubted this idea. In 1767, he published Phädon oder über die Unsterblichkeit der Seele (Phaedo or On the Immortality of Souls). This book was based on Plato's work of the same name. Mendelssohn's book was beautiful and clear. It became very popular and was translated into many languages. People called him the "German Plato" or "German Socrates."

Debates and Health Challenges

Mendelssohn had focused on philosophy and writing. However, an event changed his focus to helping Judaism. In 1769, a young theology student named Johann Kaspar Lavater challenged Mendelssohn. Lavater publicly asked him to either disprove a Christian book or convert to Christianity. Mendelssohn replied in an open letter. He said he could admire great thinkers like Confucius without needing to convert them. This public debate took a lot of his time and energy.

Lavater later described Mendelssohn as a "brilliant soul" with "keen insight." In 1775, when Swiss-German Jews faced being forced out, they asked Mendelssohn for help. He asked his friend Lavater to intervene, and Lavater successfully helped them stay.

In March 1771, Mendelssohn's health became very poor. His doctor advised him to stop philosophy for a while. He had periods of extreme anxiety and physical discomfort. Doctors at the time thought it was due to stress from the religious debate. He was treated with various remedies and told to avoid mental stress. Despite these challenges, he recovered enough to write his most important later works.

Moses Mendelssohn's Passing

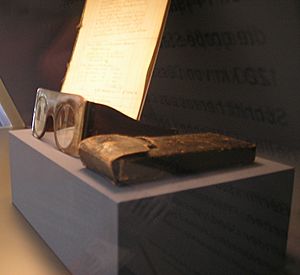

Moses Mendelssohn died on January 4, 1786. People believed he caught a cold while delivering his last manuscript to his publishers. He was buried in the Jewish Cemetery of Berlin. The cemetery was mostly destroyed during the Nazi era. However, after Germany reunited, his gravestone was recreated in 2007-2008.

Moses Mendelssohn's Philosophical Ideas

Works on Religion and Society

After his health improved, Mendelssohn decided to use his strength to help his children and his Jewish community. He wanted to bring Jews closer to general culture. One way was by giving them a better translation of the holy books. He translated the Pentateuch (the first five books of the Bible) and other parts of the Bible into German. This work was called the Bi'ur (meaning 'the explanation') and was published in 1783. The translation used elegant High German to help Jews learn the language faster. Most German Jews at that time spoke Yiddish.

Mendelssohn also worked to improve the rights and acceptance of Jews in general. He encouraged Christian Wilhelm von Dohm to publish a work in 1781. It was called On the Civil Amelioration of the Condition of the Jews. This book was very important in promoting tolerance. Mendelssohn himself translated a work called Vindiciae Judaeorum by Menasseh Ben Israel.

These efforts led Mendelssohn to publish his most important book about Judaism's place in the world. This was Jerusalem (1783). It was a strong argument for freedom of conscience. Immanuel Kant called it an "irrefutable book." Mendelssohn wrote:

Brothers, if you care for true piety, let us not pretend to agree, where differences are clearly God's plan. None of us thinks and feels exactly like another: why do we wish to trick each other with false words?

The main idea of Jerusalem is that the government should not interfere with people's religion, including Jews. He believed that Judaism was a "revealed life" rather than just a "divine need." Jerusalem ends with the powerful words "Love truth, love peace!" from the Book of Zechariah.

Kant saw this as a call for a great change that would affect many people. Mendelssohn believed that different people and nations might need different religions, just as they need different governments. The true test of a religion, he thought, was how it affected a person's actions. This idea is also central to Lessing's play Nathan the Wise. The hero of the play, Nathan, is based on Mendelssohn. The parable of the three rings in the play shows this idea of different paths to truth.

Lasting Impact and Legacy

Mendelssohn became more and more famous. He was friends with many important people of his time. However, his final years were saddened by a debate called the pantheism controversy. After his friend Lessing died, Mendelssohn wanted to write about him. Another acquaintance, Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi, claimed Lessing was a "Spinozist." At that time, this was often seen as being similar to an "atheist."

This led to a public exchange of letters between Jacobi and Mendelssohn. Mendelssohn then published Morgenstunden oder Vorlesungen über das Dasein Gottes (Morning hours or lectures about God's existence). In this book, he explained his own philosophical views and his understanding of Lessing's ideas. But Jacobi also published letters, publicly stating Lessing was a "pantheist" in the sense of an "atheist." Mendelssohn found himself in a difficult public argument. His last work, To Lessing's Friends (An die Freunde Lessings) (1786), was completed just before his death.

Mendelssohn's complete works have been published in 19 volumes.

Mendelssohn Family

Moses Mendelssohn had six children. Only his second-oldest daughter, Recha, and his eldest son, Joseph, remained Jewish. His sons were: Joseph, who founded the Mendelssohn banking house, and Abraham, who was the father of the famous composers Fanny and Felix Mendelssohn. His third son was Nathan, a respected mechanical engineer.

His daughters were Brendel (later Dorothea), Recha, and Henriette. All of them were very talented women. Joseph Mendelssohn's son Alexander (died 1871) was the last male descendant of Moses Mendelssohn to practice Judaism.

See also

In Spanish: Moses Mendelssohn para niños

In Spanish: Moses Mendelssohn para niños

- Biurists

- Fridolin Friedmann

- Sara Grotthuis

- Heinrich Josefsohn

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |