Fanny Mendelssohn facts for kids

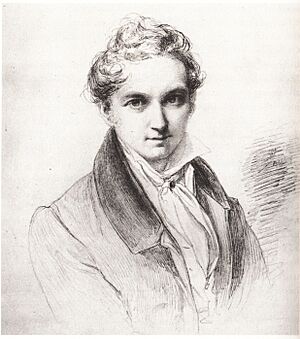

Fanny Mendelssohn (born November 14, 1805 – died May 14, 1847) was a German composer and pianist. She lived during the early Romantic period of music. She was also known as Fanny Mendelssohn Bartholdy and, after she married, Fanny Hensel.

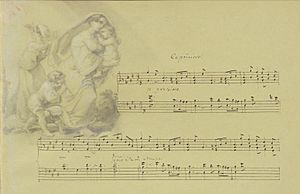

Fanny wrote many pieces of music. These include a piano trio, a piano quartet, and an orchestral overture. She also composed four cantatas, over 125 pieces for the piano, and more than 250 lieder (songs). Most of her music was not published while she was alive. People praised her piano skills, but she rarely performed in public, mostly playing for her family and friends.

She grew up in Berlin and had an excellent music education. Her teachers included her mother and famous composers like Ludwig Berger and Carl Friedrich Zelter. Her younger brother, Felix Mendelssohn, was also a composer and pianist. They had the same teachers and were very close. Because of her family's concerns and the social rules for women at that time, six of her songs were published under her brother's name. They appeared in his Opus 8 and 9 collections.

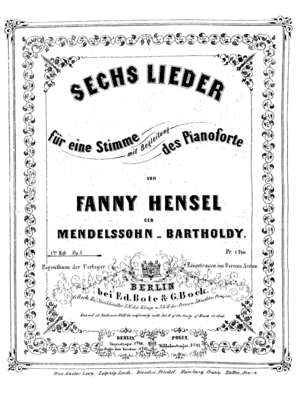

In 1829, Fanny married the artist Wilhelm Hensel. In 1830, they had their only child, Sebastian Hensel. In 1846, even though her family still had doubts about her musical goals, Fanny Hensel published a collection of her songs. This was her Opus 1. She died from a stroke in 1847.

Since the 1990s, people have studied Fanny's life and music more closely. For example, her Easter Sonata was wrongly thought to be her brother's work in 1970. But in 2010, new research proved it was hers. The Fanny & Felix Mendelssohn Museum opened in Hamburg, Germany, on May 29, 2018.

Contents

Who Was Fanny Mendelssohn?

Her Early Life and Music Education

Fanny Mendelssohn was born in Hamburg. She was the oldest of four children. Her brother, Felix Mendelssohn, was born four years after her. Her family had a long history of important Jewish scholars and business people. Her parents were Abraham Mendelssohn and Lea Salomon. Her grandfather was the famous philosopher Moses Mendelssohn.

In 1816, Fanny was baptized as a Christian and became Fanny Cäcilie Mendelssohn Bartholdy. Even so, her family still valued Jewish traditions and morals. Fanny and Felix did not like it when their father changed the family name to "Mendelssohn Bartholdy." He wanted to hide their Jewish background. Fanny wrote to Felix that "Bartholdy" was a name they all disliked.

While growing up in Berlin, Fanny showed amazing musical talent. She started writing music very early. Her mother taught her piano first. By age 14, Fanny could play all 24 preludes from Bach's The Well-Tempered Clavier from memory. She played them for her father's birthday in 1819. Fanny was also inspired by her great-aunts, Fanny von Arnstein and Sarah Levy. Both loved music, and Sarah Levy was a very skilled keyboard player.

After short lessons with pianist Marie Bigot in Paris, Fanny and Felix studied piano with Ludwig Berger. They also learned composition from Carl Friedrich Zelter. Zelter once said that Fanny was even better than Felix. In 1816, he wrote to Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, "He has adorable children and his oldest daughter could give you something of Sebastian Bach. This child is really something special." Both Fanny and Felix began learning composition from Zelter in 1819. In October 1820, they joined the Sing-Akademie zu Berlin, a famous choir led by Zelter. Later, in 1831, Zelter praised Fanny's piano playing, saying she played "like a man." Visitors to the Mendelssohn home in the 1820s, like Ignaz Moscheles, were impressed by both siblings.

Challenges for Women Composers

Music historian Richard Taruskin believes that Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel's life shows how social rules stopped women from becoming famous composers. In the 1800s, men in wealthy families usually made all the decisions. Fanny's father, Abraham, allowed her to compose but did not fully support her. In 1820, he wrote to her, "Music will perhaps become his [Felix's] profession, while for you it can and must be only an ornament."

Felix supported Fanny's music privately. However, he was careful about her publishing her works under her own name. He said it was for family reasons. Music historian Angela Mace Christian wrote that Fanny "struggled her entire life with the conflicting impulses of authorship versus the social expectations for her high-class status." She felt she had to obey her father and was aware of how society viewed women in public roles.

Henry Chorley, a friend of Felix, wrote that if Fanny had been poor, she would have been as famous as pianists like Clara Schumann and Marie Pleyel. This suggests that her social class, as well as her gender, limited her career. Fanny's son, Sebastian Hensel, wrote a biography of the family. Musicologist Marian Wilson Kimber thinks this book tried to show Fanny as someone who only wanted to perform in private. Kimber notes that Fanny's own diaries do not show a strong desire for a professional music career.

Fanny and Felix: A Musical Bond

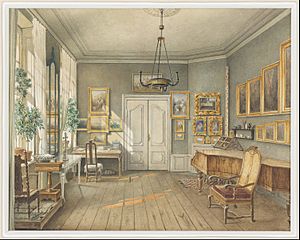

Fanny and Felix were very close because they both loved music. Fanny's works were often played alongside her brother's at their family home in Berlin. These were called "Sunday concerts." Her father first organized them, and after 1831, Fanny continued them. In 1822, when Fanny was 17 and Felix was 13, she wrote, "Up to the present moment I possess his [Felix's] unbounded confidence. I have watched the progress of his talent step by step, and may say I have contributed to his development." She added that she was always his only music adviser.

In 1826 or 1827, Felix arranged for some of Fanny's songs to be published under his name. Three were in his Opus 8 collection, and three more in his Opus 9. In 1842, this led to an awkward moment. Queen Victoria met Felix at Buckingham Palace and wanted to sing her favorite of his songs, Italien. Felix had to admit that Fanny had written it.

Fanny and Felix exchanged musical ideas throughout their lives. Fanny gave Felix helpful feedback on his pieces, and he always thought carefully about her suggestions. Felix would even change his music based on what she said. He called her "Minerva," after the Roman goddess of wisdom. Their letters from 1840-1841 show they were both planning an opera about the Nibelungenlied. Fanny wrote, "The hunt with Siegfried's death provides a splendid finale to the second act."

Marriage and Later Achievements

In 1829, after dating for several years, Fanny married the artist Wilhelm Hensel. They had first met in 1821 when she was 16. The next year, she gave birth to their only child, Sebastian Hensel.

In 1830, Fanny received her first public recognition as a composer. John Thomson, who met her in Berlin, wrote in a London newspaper called The Harmonicon. He praised several of her songs that Felix had shown him. Fanny's first public piano performance happened in 1838. She played her brother's Piano Concerto No. 1. This was one of only three known public performances she gave.

Fanny strongly supported Felix's music. In 1838, she attended rehearsals for his oratorio St. Paul in Berlin. She wrote to her brother about how frustrated she was with the slow tempo. She instinctively called out, "My God, it must go twice as fast!" After that, the conductor, Carl Friedrich Rungenhagen, asked her for advice on all the details of the rehearsals and performance. She even told them not to add a tuba to the organ part.

Wilhelm Hensel, like Felix, supported Fanny's composing. But unlike many others, he wanted her to publish her works. Music historian Nancy B. Reich suggests two things that made Fanny more confident. One was her trip to Italy with Wilhelm and Sebastian in 1839–40. This was her first time in Southern Europe, and she felt energized. They also met young French musicians who respected Fanny as a musician. The other event was meeting Robert von Keudell, a music lover in Berlin. Fanny wrote in her diary that Keudell looked at her new music with great interest and gave her good advice.

In 1846, two publishers in Berlin asked Fanny to publish her music. Without asking Felix, she decided to publish a collection of her songs as her Opus 1. She used her married name, "Fanny Hensel geb. Mendelssohn-Bartholdy." After it was published, Felix wrote to her, "I send you my professional blessing on becoming a member of the craft... may you have much happiness in giving pleasure to others." Fanny wrote in her journal that she knew Felix was not completely happy about it, but she was glad he said something kind. She also wrote to a friend that she "let it happen more than made it happen," and that she was not ambitious.

In March 1847, Fanny met with Clara Schumann many times. At this time, Fanny was working on her Piano Trio Op. 11. Clara had just finished her own Piano Trio (Op. 17).

Her Final Years

On May 14, 1847, Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel died in Berlin. She had a stroke while rehearsing one of her brother's cantatas, The First Walpurgis Night. Felix died less than six months later from the same cause. This was also the cause of death for both their parents and their grandfather Moses. Before he died, Felix finished his String Quartet No. 6 in F minor, which he wrote in memory of his sister. Fanny was buried next to her parents in a part of the Dreifaltigkeit Cemetery in Berlin. This section was for Jewish people who had converted to Christianity.

What Music Did Fanny Mendelssohn Write?

Fanny Mendelssohn composed over 450 pieces of music. Her works include a piano trio, a piano quartet, and an orchestral overture. She also wrote four cantatas, more than 125 pieces for the piano, and over 250 lieder (art songs). Six of her songs were first published under Felix's name in his Opus 8 and 9 collections.

Many of her piano pieces are like songs. They often have names like Lied für Klavier (Song for Piano). This is similar to Felix's Lieder ohne Worte (Songs Without Words). Felix developed this style of piano music very successfully. His first set appeared in 1829–30. Fanny's sets of Lieder für Klavier were written between 1836 and 1837.

Most of Fanny Mendelssohn's compositions are shorter pieces, like songs and piano works. She felt her skills were not as strong for larger, more complex pieces. Unlike her brother, she never studied or played string instruments. This experience would have helped her write music for orchestras or chamber groups. After finishing her string quartet, she wrote to Felix in 1835, "I lack the ability to sustain ideas properly and give them the needed consistency. Therefore lieder suit me best."

Despite her doubts, she was one of the first women to compose a string quartet. She also wrote a piano quartet in 1822 with Zelter's help. This was her first large-scale work. In her last year, she wrote a piano trio (Op. 11). Her Easter Sonata, written in 1828, was not published during her lifetime. It was found and thought to be her brother's in 1970. But in 2010, studying the manuscript and her diary proved it was hers.

After her marriage, most of Hensel's work was on a smaller scale. In 1831, for her son Sebastian's first birthday, she created a cantata called Lobgesang (Song of Praise). She also wrote two other works for orchestra, solo singers, and choir that year. These were Hiob (Job) and an oratorio called Höret zu, merket auf (Listen and take note).

In 1841, she composed a series of piano pieces called Das Jahr (The Year). Each piece represented a month. The music was written on colored paper and illustrated by her husband. Each piece also had a short poem. Some people think the poems, artwork, and colored paper show different stages of life, or even her own life. After Das Jahr, her only other large work was her Piano Trio Op. 11 in 1847.

Her Unique Musical Style

Angela Mace, the musicologist who proved Fanny Hensel wrote the Easter Sonata, believes Fanny was more experimental with her songs than Felix. She notes that Fanny's works have a "harmonic density" that helps express emotion.

R. Larry Todd has pointed out that both Fanny and Felix were greatly influenced by the later music of Ludwig van Beethoven. This influence can be seen in their use of form, tonality, and fugal counterpoint. For example, this is clear in Fanny's string quartet.

Musicologist Stephen Rodgers says that Fanny Hensel's music has not been studied enough. He points out her use of "triple hypermeter" in her songs. This changes the speed of the vocals and shows emotions by changing normal rhythms. He also notes that her songs often lack a clear tonic harmony. In her song Verlust (Loss), this helps show the themes of abandonment and not finding love. Fanny also often used word painting, where the music reflects the meaning of the song's words. She often used strophic form for her songs, and her piano parts often played the same tune as the voice. These were also common in the music of her teachers, Zelter and Berger. As her style grew, Rodgers suggests she started using more through-composed forms to match the poetic text.

Fanny Mendelssohn's Lasting Impact

Since the 1980s, people have become more interested in Fanny Mendelssohn and her music. The Fanny & Felix Mendelssohn Museum opened on May 29, 2018, in Hamburg, Germany. It is dedicated to the lives and work of both Fanny and Felix.

A small planet, fr:(9331) Fannyhensel, is named after her. On November 14, 2021, Google honored Fanny Hensel's 216th birthday with a Google Doodle in several countries.

Her Music Today

Six months before he died, Felix tried to make sure his sister received the recognition she deserved. He gathered many of her works, planning to publish them through his publisher, Breitkopf & Härtel. In 1850, the publisher began releasing Fanny Mendelssohn's unpublished works. They started with Vier Lieder Op. 8.

Starting in the late 1980s, Fanny Mendelssohn's music has become more widely known. This is thanks to concert performances and new recordings. Her Easter Sonata for piano, once thought to be Felix's, was performed under her name for the first time by Andrea Lam on September 12, 2012.

Writings and Studies About Her

Fanny Mendelssohn did not publish any writings during her lifetime. Some of her letters and diary entries were published in the 1800s, especially by Sebastian Hensel in his book about the Mendelssohn family. Her collected letters to Felix, edited by Marcia Citron, were published in 1987.

In the 1800s, Fanny was mostly seen as a minor figure in biographies of her brother Felix. She was sometimes described as having a "feminizing" influence that supposedly weakened his art. In the 1900s, the story changed. Felix was then seen as disapproving of his sister's musical activities and trying to limit them. The idea of her "feminizing" influence disappeared. Since the 1980s, Fanny Mendelssohn has been the subject of many academic books and articles.

A catalog of Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel's works has been created by Renate Hellwig-Unruh. Each of her works can be referred to by its "H-U number."

See also

In Spanish: Fanny Mendelssohn para niños

In Spanish: Fanny Mendelssohn para niños

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |