History of philosophy facts for kids

The history of philosophy is like a journey through time, exploring how people have thought about big questions. It looks at how ideas about the world, knowledge, and how we should live have changed. Philosophy uses logic and arguments to understand things. Sometimes, it also includes ideas from myths and religious traditions.

Western philosophy began in Ancient Greece. People wondered about the basic nature of the universe. Later, philosophers explored topics like what is real, how our mind works, how to act well, and how we know things. In the medieval period, thinking often focused on theology (the study of God). The Renaissance brought back interest in old Greek ideas and started humanism, which focused on human value. Modern philosophy looked at how knowledge is created. Its new ideas helped challenge old ways of thinking during the Enlightenment.

Arabic–Persian philosophy was greatly influenced by Ancient Greek thinkers. It was very strong during the Islamic Golden Age. Philosophers explored how reason and revelation (divine messages) could both lead to truth. Avicenna created a big system that mixed Islamic faith with Greek philosophy. Later, the influence of philosophy lessened, partly because of Al-Ghazali's criticisms. In the 17th century, Mulla Sadra developed a deep system based on mysticism. Later, Islamic modernism tried to connect old Islamic ideas with the modern world.

Indian philosophy explores the nature of reality, how we gain knowledge, and how to reach enlightenment. Its roots are in ancient religious texts called the Vedas. Indian philosophy is often split into orthodox schools, which follow the Vedas, and heterodox schools, like Buddhism and Jainism. Important schools included Advaita Vedanta and Navya-Nyāya (Hindu), and Madhyamaka and Yogācāra (Buddhist). In modern times, Indian and Western ideas mixed, leading to new systems that tried to combine different thoughts.

Chinese philosophy often focused on how people should behave, how governments should work, and self-cultivation. Early Chinese philosophy included Confucianism, which looked at moral virtues for a harmonious society. Daoism focused on the connection between humans and nature. Later, Buddhist ideas came to China and changed. New schools like Xuanxue and Neo-Confucianism appeared. Modern Chinese philosophy met Western ideas, especially Marxism. Other important traditions include Japanese philosophy, Latin American philosophy, and African philosophy.

Contents

- What is the History of Philosophy?

- Western Philosophy: A Journey Through Time

- Arabic–Persian Philosophy: Bridging Worlds

- Indian Philosophy: Paths to Enlightenment

- Chinese Philosophy: Harmony and Society

- Other Philosophical Traditions

- See also

What is the History of Philosophy?

The history of philosophy studies how philosophical ideas have grown over time. It shows how different theories are connected. Some ideas build on older ones, while others reject them. This field explains who the philosophers were and what their main ideas were. It also looks at how their times influenced their thinking.

Historians of philosophy also think about whether old theories are still true today. They look at the arguments used and if they make sense. This helps us understand old ideas and see if they are still important.

Western Philosophy: A Journey Through Time

Western philosophy comes from the ideas of the Western world. It began in Ancient Greece and then moved to the Roman Empire. Later, it spread to Western Europe and other places like North and South America. It has been around for over 2,500 years, starting in the 6th century BCE.

Ancient Greek Thinkers

Western philosophy started in Ancient Greece around 600 BCE. This period ended in 529 CE when schools in Athens were closed.

Early Greek Ideas (Presocratics)

The first period is called Presocratic philosophy. It lasted until about the mid-4th century BCE. It's hard to study because many texts only exist in small pieces.

A big change was that these early philosophers tried to explain the cosmos (the universe) using reason. Before, people used Greek mythology and stories about gods. Presocratic thinkers were some of the first to look for scientific explanations.

Thales (around 624–545 BCE) is often called the first philosopher. He thought that water was the basic source of everything. Anaximander (around 610–545 BCE) had a more abstract idea. He said the original substance was "the boundless" (apeiron), something beyond what we can see.

Heraclitus (around 540–480 BCE) believed everything is always changing, like a river you can't step into twice. He also talked about logos, an order that guides the world. Parmenides (around 515–450 BCE) disagreed. He said true reality never changes and is always one. His student Zeno of Elea (around 490–430 BCE) made famous puzzles to show that motion is an illusion.

Democritus (around 460–370 BCE) had the idea of atomism. He said everything is made of tiny, unbreakable particles called atoms. Other Presocratic philosophers included Pythagoras and the sophists.

Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle: The Big Three

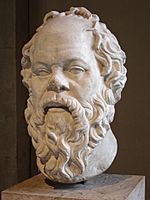

The ideas of Socrates (469–399 BCE) and Plato (427–347 BCE) changed philosophy a lot. Socrates didn't write anything. We know about him from his students, especially Plato. Socrates used the Socratic method. He would ask simple questions to explore a topic and make people think deeply. He focused on moral philosophy, asking what it means to live a good life and what virtues like justice are. He wanted people to realize what they didn't know.

Plato's writings are mostly dialogues. He taught the theory of forms. This idea says that the true nature of reality is found in perfect, unchanging forms or ideas, like the idea of beauty. The physical world we see is just an imperfect copy of these forms. Plato also thought the soul had three parts: reason, spirit, and desire. He also started the Academy, which was like the first university.

Aristotle (384–322 BCE) was Plato's student. He was a very organized philosopher. He wrote about nature, reality, logic, and ethics. He created many terms we still use today. Aristotle agreed that things have form and matter, but he thought they couldn't exist separately. He also talked about four causes that explain why things happen. For example, the "purpose" or "goal" of something is a cause. In ethics, he believed a good life means developing virtues to flourish. He also set rules for correct inferences in logic.

Hellenistic and Roman Ideas

After Aristotle, new philosophical movements appeared, like Epicureanism, Stoicism, and Skepticism. These are called Hellenistic schools. They focused on ethics, physics, and knowledge. This period lasted from 323 BCE to 31 BCE.

The Epicureans believed nature was made of atoms. In ethics, they thought pleasure was the highest good. But they meant a calm, simple life, not just luxury. They called this ataraxia (peace of mind).

The Stoics disagreed with focusing on pleasure. They saw desires as problems. They believed in self-control and being calm even when things were tough. They wanted to live in line with reason and virtue.

The skeptics wondered how our opinions affect our happiness. They said strong beliefs (dogmatic beliefs) can cause problems. They suggested that we should not make firm judgments when we can't be certain. Some even thought true knowledge was impossible.

Neoplatonism came later, from the 3rd to 6th centuries CE. It took ideas from Plato and Aristotle. Its main idea was that everything comes from a perfect, indescribable source called "the One" or "the Good." Important Neoplatonists were Plotinus (204–270 CE) and Porphyry (234–305 CE).

Medieval Philosophy: Faith and Reason

The medieval period in Western philosophy was from about 400 to 1500 CE. A big difference from earlier times was its focus on religious thought. The Christian Emperor Justinian closed many philosophy schools. Thinking was centered in the Church, and disagreeing with Church teachings was risky. Because of this, some people call it a "dark age" for philosophy. Key topics were the nature of God, proofs of God's existence, and how reason and faith fit together. Early medieval thought was shaped by Plato, while later parts were more influenced by Aristotle.

Augustine of Hippo (354–430 CE) used Plato's ideas to explain Christian beliefs. He agreed that God is good but hard to understand. He thought about the problem of evil: how can evil exist if a good, all-knowing, and all-powerful God created the world? His answer was that God gave humans free will, which means they can choose good or evil. Augustine also had ideas about God's existence and just war theory.

Boethius (477–524 CE) was interested in Greek philosophy. He translated many of Aristotle's works and tried to combine them with Christian ideas. He discussed how universal ideas (like "humanity") exist. He said they exist in our minds and also in real objects. This idea influenced later debates.

Scholasticism: Logic and Theology

The later medieval period was dominated by Scholasticism. This approach used logic and a systematic way of thinking. It was heavily influenced by Aristotle, whose works were preserved and translated by Arabic–Persian scholars.

Anselm of Canterbury (1033–1109 CE) is seen as a founder of scholasticism. He believed reason and faith work together. He is famous for his ontological argument for the existence of God. He said God is the greatest being we can imagine, and if God only existed in our minds, He wouldn't be the greatest. So, God must exist in reality. Peter Abelard (1079–1142) also stressed harmony between reason and faith. He thought universal ideas only exist as mental concepts.

Thomas Aquinas (1224–1274 CE) is often considered the most important medieval philosopher. He built a complete system of scholastic philosophy based on Aristotle's ideas. It covered reality, theology, ethics, and politics. His main goal was to show how faith and reason work together. He believed reason supports Christian beliefs, but faith is still needed for things reason can't fully grasp. In ethics, Thomas thought moral rules come from human nature. He also gave five arguments for God's existence.

William of Ockham (1285–1347 CE) was one of the last scholastic philosophers. He created Ockham's Razor. This rule says that when you have different explanations for something, the simplest one is usually the best. He used this to argue that universal ideas don't really exist outside our minds.

Renaissance Philosophy: A New Beginning

The Renaissance was from the mid-14th century to the early 17th century. It started in Italy and spread across Europe. People became interested in Ancient Greek philosophy again, especially Plato. Humanism also grew, focusing on human value and achievement. There was also a shift towards scientific thinking, moving away from the Church's control. Most scholars were no longer clerics (religious leaders).

Renaissance Platonism tried to show how Plato's ideas fit with Christian beliefs. For example, Marsilio Ficino (1433–1499) said that souls connect Plato's forms with the physical world. He thought love of knowledge was a way to connect with God.

The Renaissance also saw new ideas in political philosophy. Niccolò Machiavelli (1469–1527) argued that rulers must keep their state stable and safe, even if it means being harsh. Thomas More (1478–1535) imagined an ideal society with shared ownership and egalitarianism (equality).

New ideas in the philosophy of nature helped prepare for the scientific revolution. People started to emphasize observing things and using mathematical explanations. Francis Bacon (1561–1626 CE) was a key figure. He wrote about inductive reasoning, where you observe many things to find general rules. Galileo Galilei (1564–1642 CE) played a big role in the Copernican Revolution by arguing that the Sun, not the Earth, is the center of our Solar System.

Early Modern Philosophy: Reason and Experience

Early modern philosophy covers the 17th and 18th centuries. Philosophers were often divided into empiricists and rationalists. They both wanted a clear, systematic way to gain knowledge. This focus on method matched the scientific revolution happening at the same time. Empiricism focused on sensory experience (what we see, hear, touch). Rationalism stressed reason and innate knowledge (knowledge we are born with).

Empiricism: Learning from Experience

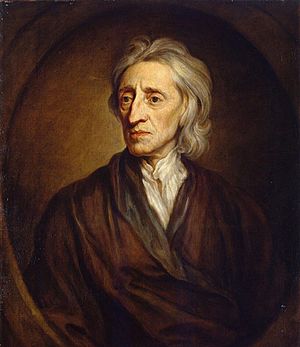

Empiricism in this period was mainly linked to British philosophy. John Locke (1632–1704) is sometimes called the father of empiricism. In his book An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, he said we are not born with knowledge. Our minds are like a blank slate that gets ideas from sensory experience. He said objects have primary qualities (like shape) that are real, and secondary qualities (like color) that are how we perceive them. George Berkeley (1685–1753) took this further. He argued that objects only exist if they are perceived. This means there is no reality outside the mind.

David Hume (1711–1776) also believed knowledge comes from experience. He thought we can't truly know that one thing causes another. We only see things happen in a regular pattern. This makes us expect one thing to follow another. Empiricism greatly influenced the scientific method, focusing on observation and testing.

Rationalism: The Power of Reason

René Descartes (1596–1650) was key to rationalism. He wanted to find absolutely certain knowledge. He doubted everything until he found something he couldn't doubt: "I think, therefore I am." From this, he built a system using deductive reasoning. He believed the body and mind are separate but exist together.

Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677) used a "geometrical method" to build his philosophy. He started with basic truths and used logic to deduce a whole system. He believed there was only one substance in reality. Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716) had the principle of sufficient reason, saying everything has a reason. He used this to create his system of monadology.

Enlightenment and Later Modern Philosophy

The Enlightenment was a big cultural movement in the later modern period. It used both empiricism and rationalism to challenge old ways of thinking. It promoted knowledge, individual freedom, and human rights. Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) was a central Enlightenment thinker. He used reason to criticize rigid beliefs. He combined empiricism and rationalism. His transcendental idealism explored how our minds shape how we experience reality. In ethics, he developed a system based on universal moral duties. Other Enlightenment philosophers included Voltaire, Montesquieu, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

Political philosophy was shaped by Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) and his book Leviathan. Hobbes thought that without government, life would be a "war of everyone against everyone." He argued that people form a social contract to give up some rights to a powerful authority for protection. Rousseau also used the idea of a social contract, but he had a more positive view of human nature and supported democracy.

19th Century: New Directions

The 19th century was a time of many different philosophical ideas. "Philosophy" became a separate subject from science and math. Some philosophers, like the German and British idealists, tried to create big, all-encompassing systems. Others, like Bentham and Mill, focused on specific areas like ethics.

German idealism was very important. It started with Immanuel Kant. Later idealists, like Johann Gottlieb Fichte (1762–1814) and Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling (1775–1854), tried to find a single principle for all reality.

The philosophy of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831) was a high point of this tradition. Hegel saw history as a journey towards freedom. He believed philosophy aims for self-knowledge, where the thinker and what is thought about become one.

Karl Marx (1818–1883) was inspired by Hegel but focused on society's historical development through class struggles. He believed economy was the main force, not spirit.

Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860) thought the basic principle of reality was the "will," an irrational force. He believed it led to suffering. This influenced Friedrich Nietzsche, who saw the will to power as a basic drive. Nietzsche used this idea to criticize many religious and philosophical concepts.

In ethics, Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832) developed utilitarianism. It says actions are right if they create the most happiness for the most people. His student John Stuart Mill (1806–1873) refined this, saying the quality of pleasure also matters.

Toward the end of the 19th century, pragmatism started in the United States. Pragmatists judge ideas by how useful and effective they are. Charles Sanders Peirce (1839–1914) founded pragmatism. He said the meaning of ideas is in their practical results. A true belief is one that works. His friend William James (1842–1910) made pragmatism more popular and applied it to psychology.

20th Century: Two Main Paths

Philosophy in the 20th century split into two main traditions: analytic philosophy and continental philosophy. Analytic philosophy, common in English-speaking countries, focused on clear language and logic to solve problems. Continental philosophy, common in Europe, included movements like phenomenology, existentialism, and postmodernism. More women philosophers also emerged in this century.

Pragmatism continued to grow with thinkers like Richard Rorty (1931–2007). The 20th century also saw the rise of feminism, which questioned traditional ideas that put women at a disadvantage. Key feminist philosophers include Simone de Beauvoir (1908–1986) and Judith Butler (1956–present).

Analytic Philosophy: Clear Thinking

George Edward Moore (1873–1958) helped start analytic philosophy. He believed in common sense and argued against extreme skepticism. In ethics, he said our actions should promote good, and "good" can't be defined but is known through intuition.

Gottlob Frege (1848–1925) was another pioneer. He developed modern symbolic logic, which greatly influenced philosophy. He tried to show that arithmetic could be based purely on logic. Bertrand Russell (1872–1970) had a similar goal for math. Russell's theory of definite descriptions explained how to understand phrases like "the present King of France." He also developed logical atomism, saying the world is made of basic facts.

His student Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889–1951) first agreed that the world and language share a logical structure. But later, he changed his mind. He argued that language is like many different games, each with its own rules. Meaning comes from how we use words, not from them referring to facts.

Logical positivism grew from empiricism, focusing on logic and checking ideas with experience. Rudolf Carnap (1899–1970) said a statement is meaningless if it can't be checked by senses or logic. He used this to reject metaphysics. His student Willard Van Orman Quine (1908–2000) criticized this idea. Quine believed that natural sciences give us the most reliable way to understand the world.

Wittgenstein's later ideas were part of ordinary language philosophy, which looked at everyday language to understand philosophical problems. John Langshaw Austin (1911–1960) developed the theory of speech acts. This shift to focusing on language is called the linguistic turn.

Continental Philosophy: Experience and Interpretation

Phenomenology was an important early movement in continental philosophy. It tried to describe human experience from a personal viewpoint. Its founder was Edmund Husserl (1859–1938). He stressed putting aside all old beliefs to describe experience purely. His student Martin Heidegger (1889–1976) used this to explore how our understanding of reality shapes our experience. He thought interpretation was also needed. This was developed further by Hans-Georg Gadamer (1900–2002), who talked about a "fusion of horizons" when we interpret things.

Heidegger also focused on how humans care about the world, linking it to anxiety and authenticity. These ideas influenced Jean-Paul Sartre (1905–1980), who developed existentialism. Existentialists believe humans are free and responsible for their choices. They also say life has no set purpose, which can cause anxiety. Albert Camus (1913–1960) emphasized the idea that the universe is meaningless (absurdism).

Critical Theory started in the Frankfurt School in the early 20th century. It's a type of social philosophy that looks at and criticizes society and culture. Its goal is not just to understand, but to bring about change and free people from unfair power. Key themes include power, inequality, and social justice. Important figures were Theodor Adorno (1903–1969) and Max Horkheimer (1895–1973).

The later 20th century in continental philosophy questioned many old ideas like truth, objectivity, and reason. This is sometimes called postmodernism. Michel Foucault (1926–1984) looked at how knowledge and power are linked. Jacques Derrida (1930–2004) developed deconstruction, which tries to find hidden contradictions in texts. Gilles Deleuze (1925–1995) used ideas from psychology to rethink concepts like desire and subjectivity.

Arabic–Persian Philosophy: Bridging Worlds

Arabic–Persian philosophy is the tradition from Arabic- and Persian-speaking regions. It's also called Islamic philosophy.

Its classical period began in the early 9th century CE and lasted until the late 12th century CE. This was part of the Islamic Golden Age. Early on, it focused on translating and understanding Ancient Greek philosophy. Later, it was shaped by Avicenna's ideas.

Arabic–Persian philosophy was very important for Western philosophy. Many Greek texts were lost in Western Europe during the early medieval period. They became available again thanks to Arabic–Persian scholars who preserved and shared them.

Early Islamic Thought

Early Arabic thought had many theological discussions about understanding the Islamic revelation. Some historians see this as philosophy, while others distinguish between theology (kalam) and philosophy (falsafa). Theologians focused on religious questions, like proving God's existence. Philosophers explored a wider range of topics, even those not directly in scriptures.

Early Arabic–Persian philosophy was strongly influenced by Ancient Greek ideas, especially Aristotle and Plato. Scholars translated and wrote commentaries on these works. A main goal was to combine Greek philosophy with Islamic thought. Philosophers looked at how reason and revelation could work together to find truth.

Al-Kindi (801–873) is often seen as the first philosopher in this tradition. He believed metaphysics (the study of reality) was the highest science, focusing on God's nature. He used the idea of "the One" from Plotinus to argue for God's oneness. He thought God created the universe from nothing. Al-Kindi also believed humans have immortal souls separate from their mortal bodies.

Al-Farabi (around 872–950) was influenced by Al-Kindi. He thought philosophy was the best way to truth. He was very interested in logic and was called "the second master" after Aristotle. He believed logic was universal and the basis of all language and thought. In political philosophy, Al-Farabi liked Plato's idea of a philosopher-king.

Later Classical Islamic Philosophy

Avicenna (980–1037) built a complete philosophical system from Ancient Greek and Al-Farabi's ideas. He wanted to understand reality using science, religion, and mysticism. He saw logic as the base of rational thinking. In metaphysics, he said substances (like a table) can exist alone, but accidents (like its color) need something else to exist. He also said God has necessary existence, meaning God must exist. Everything else exists only because God caused it. In psychology, he saw souls as what gives life to things. In ethics, he suggested seeking moral perfection by following the Quran. His system greatly influenced both Islamic and Western philosophy.

Al-Ghazali (1058–1111) strongly criticized Avicenna's rational approach. He doubted if reason alone could truly understand reality, God, and religion. In his book The Incoherence of the Philosophers, he said many philosophical ideas had contradictions and didn't fit with Islamic faith. However, he wasn't completely against philosophy. He thought it had a positive but limited role, and should be combined with mystical intuition.

Averroes (1126–1198) disagreed with Al-Ghazali's doubts. He tried to show how philosophy and faith could work together. He relied heavily on Aristotle's teachings. Averroes believed there was only one universal intellect shared by all humans. He didn't influence later Islamic scholars much, but he had a bigger impact on European philosophy.

Post-Classical Islamic Philosophy

After Averroes, the traditional view is that Islamic philosophy declined. However, some scholars now say it was more of a shift in focus. Philosophy didn't stop, but was absorbed into theology.

Mulla Sadra (1571–1636) is seen as the most important philosopher after the classical era. He belonged to the illuminationism school, which mixed philosophy and mysticism. He thought philosophy was a spiritual practice to gain wisdom. In metaphysics, he had an important theory of existence. He rejected the idea that reality is made of fixed substances. Instead, he believed in a process philosophy where everything is constantly changing. He also argued that all things are conscious to different degrees.

Islamic modernism appeared in the 19th and 20th centuries. It tried to understand how traditional Islamic ideas fit into the modern world. Islamic modernists wanted to adapt Islamic teachings to be compatible with modern ideas like democracy, human rights, science, and against colonialism.

Indian Philosophy: Paths to Enlightenment

Indian philosophy comes from the Indian subcontinent. It's known for its deep interest in ultimate reality and how to connect with the divine to reach enlightenment. Indian philosophers often acted as gurus, guiding spiritual seekers.

Indian philosophy is divided into orthodox and heterodox schools. Orthodox schools usually accept the Vedas (religious scriptures) as authority. They often believe in the self (Atman) and ultimate reality (Brahman). There are six orthodox schools: Nyāyá, Vaiśeṣika, Sāṃkhya, Yoga, Mīmāṃsā, and Vedānta. Heterodox schools don't accept the Vedas. The main ones are Buddhism and Jainism.

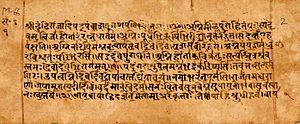

Ancient Indian Thought

The ancient period in Indian philosophy was from about 900 BCE to 200 BCE. The Vedas were written then. The Upanishads, which are later Vedic texts, discuss philosophical topics like Atman (the eternal soul) and Brahman (ultimate reality). They explore how Atman and Brahman are connected and how understanding this can lead to liberation. Some Upanishads suggest an ascetic life (withdrawing from the world), while others emphasize active engagement and social duties (dharma). Another key idea is rebirth, where a person's actions (karma) in one life affect the next.

Not all Indian philosophy came from the Vedas. Buddhism and Jainism emerged in the 6th century BCE. They agreed with rebirth and liberation but rejected many Vedic rituals. Buddhism was founded by Gautama Siddhartha (563–483 BCE). He challenged the idea of a permanent self, saying that believing in one leads to suffering. Liberation comes from realizing there is no permanent self.

Jainism was founded by Mahavira (599–527 BCE). Jainists practice non-violence towards all life. They also believe there are no absolute truths because reality is complex. Another pillar is non-attachment to worldly things.

Classical and Medieval Indian Thought

This period was from about 200 BCE to 1800 CE. The orthodox schools, called darsanas, developed. Their main texts are sūtras (short sayings). Later, detailed commentaries were written to explain these sutras.

Samkhya is the oldest darśana. It's a dualistic philosophy, saying reality has two parts: Purusha (pure consciousness) and Prakriti (matter). Prakriti has three qualities called gunas: Sattva (calmness), Rajas (passion), and tamas (ignorance). The Yoga school started as part of Samkhya and focuses on physical postures and meditation.

Nyaya and Vaisheshika are other orthodox schools. Nyaya focuses on sources of knowledge: perception, inference, analogy, and testimony. It developed an important theory of logic. Vaisheshika is known for its atomistic view of reality.

The schools of Vedānta and Mīmāṃsā interpret the Vedic scriptures. Vedānta focuses on the Upanishads, discussing reality, knowledge, and liberation. Mīmāṃsā is more about the rituals in the Vedas.

Buddhist philosophy also grew, with four main schools: Sarvāstivāda, Sautrāntika, Madhyamaka, and Yogācāra. They all agreed with Gautama's core teachings but had differences. For example, Madhyamaka, founded by Nagarjuna (around 150–250), said all things are "empty," meaning they don't have a permanent essence. Yogācāra is often seen as a form of idealism, saying the outside world is an illusion created by the mind.

The Vedanta school became very important. Advaita Vedanta, influenced by Adi Shankara (around 700–750), defended a radical monism. It said Atman and Brahman are the same, and the idea of many separate things in the universe is an illusion.

Ramanuja (1017–1137) developed Vishishtadvaita Vedanta. He agreed Brahman is ultimate reality but said individual things are also real as parts of Brahman. He emphasized Bhakti (devotion) as a spiritual path.

Modern Indian Philosophy

The modern period began around 1800 CE. British rule and English education brought many changes. Philosophers started writing in English, like Surendranath Dasgupta (1887–1952) with his A History of Indian Philosophy. Indian philosophers were influenced by both their own traditions and Western ideas.

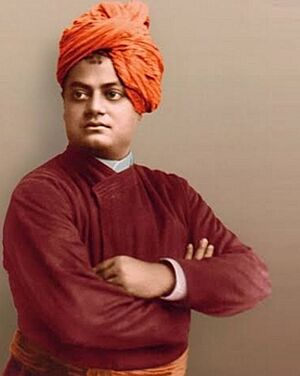

Many philosophers tried to combine different ideas. Swami Vivekananda (1863–1902) said all religions are valid paths to the same spiritual truth. He used Advaita Vedanta to show that different religions are ways to realize the divine oneness hidden by the world's diversity.

Sri Aurobindo also tried to create a system that showed how different historical and philosophical movements are part of a global evolution of consciousness. Other spiritual teachers like Sri Ramakrishna and Jiddu Krishnamurti also contributed.

Chinese Philosophy: Harmony and Society

Chinese philosophy covers the ideas from China. The three main schools are Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism. Other important ones are Mohism and Legalism.

In traditional Chinese thought, philosophy wasn't strictly separate from religion. It focused on ethics and society, less on deep reality. Philosophers often gave practical wisdom and advised leaders.

Early Chinese Thought (Pre-Qin)

The first period was from the 6th century BCE until the Qin dynasty in 221 BCE. The concept of Dao ("the Way") was central. Confucius (551–479 BCE) believed a good life meant following the Dao through moral behavior and virtues. He stressed respect for elders and universal altruism. The family was key, and he saw the state as a big family needing harmony.

Laozi (6th century BCE) founded Daoism. He also believed in living in harmony with the Dao, but focused more on nature than just society. His idea of wu wei ("effortless action") was important. It means acting naturally and spontaneously, in line with the Dao.

The Daoist philosopher Zhuangzi (399–295 BCE) used stories to explain his ideas. His "butterfly dream" story questioned what is real: was he a man dreaming of being a butterfly, or a butterfly dreaming of being a man?

The school of Mohism was founded by Mozi (around 470-391 BCE). He believed in jian ai, a form of universal love. He argued that political actions should help everyone.

Qin to Pre-Song Dynasties

This period was from 221 BCE to 960 CE. It included Xuanxue philosophy, legalist philosophy, and the spread of Chinese Buddhism. Xuanxue, or neo-Daoism, tried to mix Confucianism and Daoism. It explored if the Dao, as the root of reality, was "being" or "non-being."

Legalism became very influential in ethics and politics. Legalists believed statecraft was about using power and creating order, not promoting general welfare. They thought strict laws and punishments were the best way to achieve a stable society, not virtues.

Buddhism arrived in China in the 1st century CE. At first, philosophers translated texts. Later, unique forms of Chinese Buddhism developed. Tiantai Buddhism (6th century CE) tried to combine different ideas about reality. Chan Buddhism also rose, which later became Zen Buddhism in Japan. Chan Buddhists believed in direct understanding of things, without language getting in the way.

Song to Qing Dynasties and Modern Era

This period started in 960 CE. Neo-Confucianism was very important. Unlike earlier Confucianism, it focused more on metaphysics (the nature of reality). It emphasized the concept of li, a rational principle that is the basis of everything and guides human nature and virtues. Li was sometimes contrasted with qi, a material force.

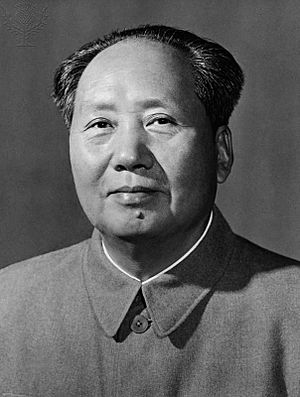

The later Qing dynasty and modern period saw Chinese philosophy meet Western ideas, especially Marxism. Marx's ideas about class struggle and communism led to Chinese Marxism. Mao Zedong (1893–1976) was a philosopher and revolutionary leader who applied these ideas. Mao's Marxism differed from classical Marxism, for example, by giving the main role in revolution to the peasantry instead of the working class.

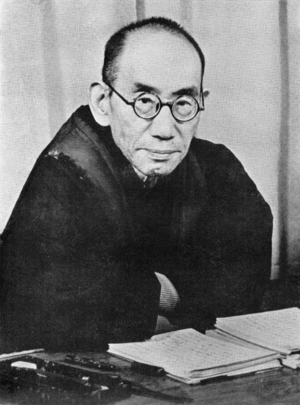

Traditional Chinese thought remained strong. Liang Shuming (1893-1988) was influenced by Confucianism, Buddhism, and Western philosophy. He founded new Confucianism. He believed in a balanced life, harmonizing humanity and nature for true happiness. He criticized Western society for focusing too much on exploiting nature.

Other Philosophical Traditions

Many other traditions developed their own unique philosophical ideas. Some grew independently, while others were influenced by the main traditions.

Japanese Philosophy

Japanese philosophy combines ideas from Chinese, Indian, and Western traditions. Ancient philosophy was shaped by Shinto, Japan's native religion, which saw spirits (kami) in nature. Confucianism and Buddhism arrived later, changing intellectual thought. Confucianism influenced political and social ideas. Japanese Buddhist thought developed into Pure Land Buddhism and Zen Buddhism. In the 19th and 20th centuries, Western thinkers like existentialists and phenomenologists influenced Japanese philosophy. The Kyoto School was founded by Kitaro Nishida (1870–1945). He criticized Western philosophy for separating subject and object. He developed the concept of basho ("place"), an area of experience that goes beyond this separation.

Latin American Philosophy

Philosophy in Latin America is often grouped with Western philosophy, but it has its own unique features. Indigenous civilizations like the Aztecs, Maya, and Inca had philosophical ideas about reality and humans before Europeans arrived. However, few texts from this time survived. The colonial period focused on religious philosophy. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the focus shifted to Enlightenment ideas and science. In the late 20th century, the philosophy of liberation emerged, inspired by Marxism. It focused on political freedom, intellectual independence, and education.

African Philosophy

African philosophy covers ideas from across the African continent. It comes from ancient Egypt and medieval African texts. Early African thought included folklore and wise sayings, as well as philosophical ideas like Ubuntu. Ubuntu means humanity or humanness. It emphasizes that people are connected and should practice kindness. In the 17th century, Ethiopian philosophy developed a literary tradition, like the work of Zera Yacob. Systematic African philosophy often dates to the early 20th century. One movement, excavationism, tried to rebuild traditional African worldviews to find a lost African identity. Other important ideas in modern African thought include ethnophilosophy, négritude, pan-Africanism, Marxism, and the critique of Eurocentrism.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de la filosofía occidental para niños

In Spanish: Historia de la filosofía occidental para niños

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |