Upanishads facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Upanishads |

|

|---|---|

|

|

|

| Information | |

| Religion | Hinduism |

| Language | Sanskrit |

| Hindu texts |

| Śruti

Smriti |

The Upanishads (pronounced: Oo-pah-nish-adz) are important Sanskrit texts from ancient India. They are a key part of the Vedas, which are the oldest scriptures of Hinduism. The Upanishads explore deep ideas about meditation, philosophy, and what it means to be alive.

These texts mark a shift in ancient Indian thought. Earlier parts of the Vedas focused on prayers, rituals, and sacrifices. But the Upanishads began to explore new religious ideas. They discuss the connection between rituals, the universe (including gods), and humans. A main idea is about Ātman (the true self or soul) and Brahman (the ultimate reality of the universe).

There are about 108 known Upanishads. The first twelve or so are the oldest and most important. They are called the main (mukhya) Upanishads. For many centuries, these main Upanishads were learned by heart and passed down by speaking. They were written before the Common Era, but their exact dates are still debated by scholars.

The Upanishads have influenced many later Hindu traditions. They also caught the attention of Western thinkers in the 1800s. For example, the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer loved them. He called them "the most profitable and elevating reading" possible.

Contents

What Does 'Upanishad' Mean?

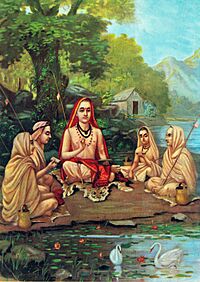

The word Upanishad comes from Sanskrit. It originally meant "connection" or "equivalence." But it became known as "sitting near a teacher." This refers to a student sitting close to a teacher to learn spiritual knowledge.

Other meanings include "secret doctrine" or "hidden knowledge." The Sanskrit Dictionary by Monier-Williams says it means "ending ignorance by showing the knowledge of the supreme spirit."

Adi Shankara, an important Hindu philosopher, explained it as Ātmavidyā (knowledge of the self) or Brahmavidyā (knowledge of Brahman). The word appears in many Upanishads. Scholars like Max Müller and Paul Deussen translate it as "secret doctrine." Others, like Patrick Olivelle, call it "hidden connections."

How the Upanishads Developed

Who Wrote the Upanishads?

Most Upanishads were written by unknown authors. Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, a former President of India and philosopher, noted that much of ancient Indian literature was anonymous. The ancient Upanishads are part of the Vedas. Some traditions believe the Vedas are apauruṣeya, meaning "not of a man" or "authorless." However, Vedic texts also say that wise Rishis (sages) created them with great skill.

Many philosophical ideas in the early Upanishads are linked to famous sages. These include Yajnavalkya, Uddalaka Aruni, and Shvetaketu. Women like Maitreyi and Gargi also took part in these discussions. They are mentioned in the early Upanishads. One exception is the Shvetashvatara Upanishad. It names sage Shvetashvatara as its author.

Many experts believe that the early Upanishads were changed and added to over time. Different copies of the same Upanishad have been found in various parts of South Asia. These copies show differences in style, grammar, and structure. This suggests that many people worked on these texts.

When Were the Upanishads Written?

It is hard for scholars to say exactly when the Upanishads were written. Philosopher Stephen Phillips says that dating them is difficult. This is because opinions are based on little evidence. They rely on how old the language seems, the style, and repeated parts.

Patrick Olivelle, a scholar of Indian studies, says that trying to be too precise with dates is like building "a house of cards." Most scholars give wide time frames. Gavin Flood states that the older Upanishads were written between 600 and 300 BCE. Stephen Phillips places the main Upanishads between 800 and 300 BCE.

Olivelle suggests this timeline for the early Upanishads:

- The Brhadaranyaka and the Chandogya are the oldest. They might be from the 7th to 6th centuries BCE.

- The Taittiriya, Aitareya, and Kausitaki Upanishads came next. They are likely from the 6th to 5th centuries BCE.

- The Kena is the oldest verse Upanishad. After it came the Katha, Isa, Svetasvatara, and Mundaka. These were likely written in the last few centuries BCE.

- The Prasna and Mandukya Upanishads are later. They might be from around the beginning of the Common Era.

Later Upanishads, about 95 of them, are called minor Upanishads. They were written from the late 1st millennium BCE to the mid-2nd millennium CE.

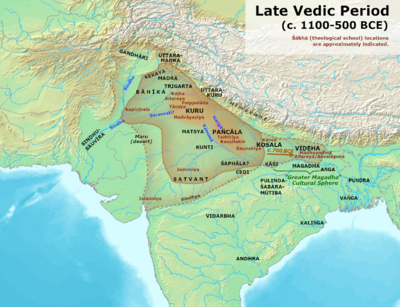

Where Were the Upanishads Written?

The early Upanishads were mostly written in northern India. This area includes modern Bihar, Nepal, Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, Haryana, eastern Rajasthan, and northern Madhya Pradesh.

Scholars believe the main Upanishads were created in the heart of ancient Brahmanism. This area was known as Kuru-Panchala and Kosala-Videha.

The newer Upanishads, listed in the Muktikā collection, come from a different region. They were probably written in southern India and are much more recent.

Types of Upanishads

Main and Minor Upanishads

There are over 200 known Upanishads. One of them, the Muktikā Upanishad, lists 108 official Upanishads. These 108 are further grouped by their focus. Some are about Shaktism (goddess Shakti), Sannyasa (giving up worldly life), Shaivism (god Shiva), Vaishnavism (god Vishnu), Yoga, and general topics (Sāmānya).

Some Upanishads are called "sectarian." This means they focus on a specific god or goddess, like Vishnu or Shiva. These texts tried to connect themselves to the Vedas by calling themselves Upanishads. Most of these sectarian Upanishads say that all Hindu gods and goddesses are different forms of Brahman. Brahman is the ultimate reality before and after the universe was created.

The Principal Upanishads

The Principal Upanishads, also called Mukhya Upanishads, are the most important. The Brihadaranyaka and Chandogya are the oldest among them. They are believed to be older than Gautam Buddha (around 500 BCE).

The Aitareya, Kauṣītaki, and Taittirīya Upanishads might be from the mid-1st millennium BCE. The rest are from roughly the 4th to 1st centuries BCE. Not much is known about their authors, except for those mentioned in the texts. A few women, like Gargi and Maitreyi, also appear in discussions.

Each Principal Upanishad is linked to one of the four Vedas. Many schools of Vedic study (shakhas) once existed, but only a few remain. The newer Upanishads often have little connection to the Vedas. Their language is also simpler and more direct than the classic Upanishads.

| Veda | Main Upanishad |

|---|---|

| Rig Veda | Aitareya |

| Sama Veda | Chāndogya |

| Kena | |

| Yajur Veda | Kaṭha |

| Taittirīya | |

| Īśa | |

| Bṛhadāraṇyaka | |

| Atharva Veda | Muṇḍaka |

| Māṇḍūkya | |

| Praśna |

Newer Upanishads

The list of Upanishads is not fixed. New ones have been found and written over time. For example, in 1908, four new Upanishads were discovered.

Ancient Upanishads are highly respected in Hindu traditions. Because of this, many authors of newer texts tried to gain respect by calling their writings "Upanishads." These "new Upanishads" number in the hundreds. They cover many topics, from how the body works to giving up worldly life. They were written from the last centuries of the 1st millennium BCE to the early modern era (around 1600 CE). These newer texts are not considered Vedic texts. Some do not even discuss the same themes as the older Upanishads.

These sectarian texts, like some from Shakta traditions, do not have the same authority as the original Upanishads. Their ideas are not accepted as shruti (revealed scripture) in Hinduism.

How Upanishads are Linked to the Vedas

All Upanishads are connected to one of the four Vedas: Rigveda, Samaveda, Yajurveda (which has two main versions), and Atharvaveda. In modern times, the ancient Upanishads were separated from the larger Vedic texts. They were then put into collections. These lists connected each Upanishad to one of the four Vedas.

Many such lists exist, but they are not always the same across India. In South India, a list of 108 Upanishads, based on the Muktika Upanishad, became common. In North India, a list of 52 Upanishads was more common.

The Muktikā Upanishad's list of 108 Upanishads groups them as follows: 13 are mukhya (main), 21 are general, 20 are about giving up worldly life, 14 are about Vishnu, 12 are about Shiva, 8 are about Shakti, and 20 are about Yoga. The mukhya Upanishads are the most important.

Main Ideas of the Upanishads

The Upanishads try to understand the links between rituals, the universe, and human beings. They suggest that Ātman (the self) and Brahman (the ultimate reality) are the most important parts of the universe. However, different Upanishads have different ideas about how Atman and Brahman are related.

The Upanishads show many different ways of looking at the world. Some are 'monistic,' meaning they believe in one ultimate reality. Others, like the Katha Upanishad, are 'dualistic,' meaning they see two separate realities. The Maitri Upanishad, for example, leans more towards dualism.

The Upanishads include ideas that are foundational to Indian traditions. For instance, the Chandogya Upanishad has one of the earliest mentions of Ahimsa (non-violence) as a moral rule. Other ethical ideas like Damah (self-control), Satya (truthfulness), Dāna (charity), and Daya (compassion) are also found in the oldest Upanishads. The idea of Karma is also explained in the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, which is the oldest Upanishad.

From Rituals to Inner Thought

The Vedas focused on rituals and ceremonies. But the Upanishads began to move away from this. The older Upanishads criticize rituals more and more. The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad says that anyone who worships a god other than their own self is like an animal owned by the gods. The Chāndogya Upanishad even makes fun of people who do sacrifices. It compares them to dogs chanting "Om! Let's eat. Om! Let's drink."

The Kaushitaki Upanishad says that outer rituals, like morning and evening offerings, should be replaced with inner ones. It suggests that knowledge, not rituals, should be the goal. The Mundaka Upanishad calls sacrifices and good deeds "foolish and weak." It says they are like "blind men leading the blind" and are useless.

The Maitri Upanishad states:

The purpose of all sacrifices is to lead to knowledge of Brahman. This prepares a person for meditation. So, after performing these rituals, one should meditate on the Self to become complete. But what should one meditate on?

The Upanishads also changed how they viewed the Vedic gods. Gods like Agni, Indra, and Vishnu became linked to the supreme, eternal Brahman-Atman. God became the same as the self. It was said to be everywhere, inside every person and living creature. The one reality of the Vedas became "the one and only and without a second" in the Upanishads. Realizing Brahman-Atman and the self became the way to moksha (freedom or liberation).

Atman and Brahman

The Upanishads talk about Ātman and Brahman as the most important parts of the universe. Both words have many meanings.

Atman can mean "breath," "spirit," or "body." In the Upanishads, it refers to the body, but also to the true essence of a person. It can mean a life-force, consciousness, or the ultimate reality. The Chāndogya Upaniṣhad describes Atman as the life force that gives life to all living things. The Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣhad sees Atman more as consciousness.

Brahman can mean "a statement of truth." But it also refers to "the ultimate and basic essence of the cosmos." It is beyond what humans can see or think. Atman also means 'self,' the inner essence of a person.

There are different ideas about how Atman and Brahman are related. Older Upanishads say that Atman is part of Brahman but not exactly the same. Younger Upanishads say that Brahman (the highest reality) is the same as Atman. The Brahmasutra by Badarayana (around 100 BCE) tried to combine these ideas. It said Atman and Brahman are both different and not different. This led to many different theories in Hinduism.

Reality and Maya

The Upanishads describe the universe and human experience as an interaction between Purusha (the eternal, unchanging consciousness) and Prakṛti (the temporary, changing natural world). Purusha shows up as Ātman (the soul or self). Prakṛti shows up as Māyā.

The Upanishads call the knowledge of Atman "true knowledge" (Vidya). They call the knowledge of Maya "not true knowledge" (Avidya).

Hendrick Vroom explains that Maya in the Upanishads doesn't mean the world isn't real. It means the world is not what it seems. The world we experience can be misleading about its true nature. Wendy Doniger says that saying the universe is Maya means it's not unreal, but it's constantly being made. Maya not only tricks people, but it also limits their knowledge.

In the Upanishads, Maya is the changing reality we see. It exists alongside Brahman, which is the hidden true reality. Maya is important because the texts say it hides, confuses, and distracts people from finding blissful self-knowledge.

Schools of Vedanta

The Upanishads are one of the three main sources for all schools of Vedanta. The other two are the Bhagavad Gita and the Brahmasutras. Because the Upanishads have many different teachings, they can be understood in various ways. The Vedanta schools try to answer questions about the relationship between Atman and Brahman, and between Brahman and the world.

The schools of Vedanta are named after how they see the connection between Atman and Brahman:

- Advaita Vedanta says there is no difference. Atman and Brahman are one.

- Vishishtadvaita says the individual soul (jīvātman) is a part of Brahman. So, it is similar but not exactly the same.

- Dvaita says all individual souls and matter are eternal and separate from each other.

Other Vedanta schools include Nimbarka's Dvaitadvaita and Vallabha's Suddhadvaita. The philosopher Adi Shankara wrote important comments on 11 main Upanishads.

Advaita Vedanta

Advaita means "non-duality." It is a system that believes in one ultimate reality. It focuses on the idea that Brahman and Atman are not two separate things. Advaita is a very important school of Hindu philosophy.

Gaudapada was the first to explain the main ideas of Advaita. He wrote comments on the Upanishads. Adi Shankara (8th century CE) further developed Gaudapada's ideas. Shankara used the early Upanishads to explain the key difference between Hinduism and Buddhism. He said Hinduism believes that Atman (the soul or self) exists, while Buddhism does not.

The Upanishads contain four famous sentences called the Mahāvākyas (Great Sayings). Shankara used these to show that Atman and Brahman are the same:

- "Prajñānam brahma" - "Consciousness is Brahman" (Aitareya Upanishad)

- "Aham brahmāsmi" - "I am Brahman" (Brihadaranyaka Upanishad)

- "Tat tvam asi" - "That Thou art" (Chandogya Upanishad)

- "Ayamātmā brahma" - "This Atman is Brahman" (Mandukya Upanishad)

Vishishtadvaita

The second school of Vedanta is Vishishtadvaita, started by Ramanuja (1017–1137 CE). Ramanuja disagreed with Adi Shankara. Vishishtadvaita combines ideas from both monistic (one reality) and theistic (belief in a personal god) Vedanta. Ramanuja often quoted the Upanishads. He said that Vishishtadvaita is based on them.

Ramanuja interpreted the Upanishads as teaching a "body-soul" idea. He believed Brahman lives in all things, but is also separate from them. Brahman is like the soul, the inner controller, and is immortal. According to Vishishtadvaita, the Upanishads teach that individual souls are similar to Brahman, but not exactly the same in quantity.

In Vishishtadvaita, the Upanishads are seen as teaching about Ishvara (Vishnu). Ishvara is full of good qualities. The world we see is the body of God, who lives in everything. This school suggests devotion to God and always remembering the beauty of a personal god. This eventually leads to becoming one with the abstract Brahman. For Ramanuja, the Brahman in the Upanishads is a living reality and "the Atman of all things and all beings."

Dvaita

The third school of Vedanta is Dvaita, started by Madhvacharya (1199–1278 CE). This school is very focused on the idea of a personal God. Madhvacharya, like Shankara and Ramanuja, said his Dvaita Vedanta was based on the Upanishads.

According to the Dvaita school, when the Upanishads say the soul is Brahman, they mean it is similar, not identical. Madhvacharya interpreted the Upanishadic idea of the self becoming one with Brahman as "entering into Brahman." This is like a drop entering an ocean. For the Dvaita school, this means there is a difference and dependence. Brahman and Atman are different realities. Brahman is a separate, independent, and supreme reality. Atman only looks like Brahman in a limited and dependent way, according to Madhvacharya.

Unlike Ramanuja's and Shankara's schools, which believe all souls can achieve liberation, Madhvacharya believed some souls are eternally doomed.

Translations of the Upanishads

The Upanishads have been translated into many languages. These include Persian, Italian, Urdu, French, Latin, German, and English.

During the reign of the Mughal Emperor Akbar (1556–1586), the Upanishads were first translated into Persian. His great-grandson, Dara Shukoh, created a collection called Sirr-i-Akbar in 1656. It had 50 Upanishads translated from Sanskrit into Persian.

Anquetil-Duperron, a French scholar, got a copy of the Oupanekhat. He translated the Persian version into French and Latin. He published the Latin translation in 1801–1802. This Latin version was the first time Western scholars were introduced to Upanishadic ideas. However, some scholars say the Persian translators changed the meaning quite a bit.

The first Sanskrit-to-English translation of the Aitareya Upanishad was by Colebrooke in 1805. The first English translation of the Kena Upanishad was by Rammohun Roy in 1816.

Max Mueller's editions in 1879 and 1884 were the first complete English translations of the 12 Principal Upanishads. Other important translations have been made by Robert Ernest Hume, Paul Deussen, Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, and Patrick Olivelle. Olivelle's translation won an award in 1998.

In the 1930s, the Irish poet W. B. Yeats worked with the Indian teacher Shri Purohit Swami. They created their own translation of the Upanishads, called The Ten Principal Upanishads, published in 1938. This was the last work Yeats published before he died.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Upanishad para niños

In Spanish: Upanishad para niños

- Bhagavad Gita

- Hinduism

- Principal Upanishads