Indian philosophy facts for kids

|

||||||

Indian philosophy explores the many ways people in the Indian subcontinent have thought about life, the world, and how we gain knowledge. These ideas are often grouped into two main types: 'orthodox' (āstika) and 'heterodox' (nāstika). The main difference is whether they accept the ancient sacred texts called the Vedas as true knowledge.

There are six major orthodox schools of Vedic philosophy: Nyaya, Vaisheshika, Samkhya, Yoga, Mīmāṃsā, and Vedanta. There are also five main heterodox schools: Jain, Buddhist, Ajivika, Ajñana, and Charvaka. The orthodox groups believe in the Vedas as a key source of their ideas, while the heterodox groups do not.

Most of the main Indian philosophies were formally recognized between 500 BCE and the later centuries of the Common Era. These different schools often debated and influenced each other. Some, like Jainism, Buddhism, Yoga, and Vedanta, are still active today. Others, like Ajñana, Charvaka, and Ājīvika, have mostly disappeared.

Ancient and medieval Indian texts discuss many important topics. These include:

- Ontology (the study of what exists, like Brahman and Atman or Sunyata and Anatta)

- Reliable ways of knowing things (epistemology, or Pramanas)

- Value systems (axiology)

Contents

Common Ideas in Indian Philosophy

Indian philosophies share many ideas. These include:

- Dharma (right conduct or duty)

- Karma (actions and their results)

- Samsara (the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth)

- Dukkha (suffering or dissatisfaction)

- Renunciation (giving up worldly desires)

- Meditation

Almost all of them aim for the ultimate goal of freeing a person from suffering and the cycle of rebirth. This freedom is called moksha or nirvana. However, they have different ideas about how to reach this goal and what reality is truly like. This led to many schools disagreeing with each other. Their ancient teachings cover a wide range of philosophical thoughts, similar to those found in other old cultures.

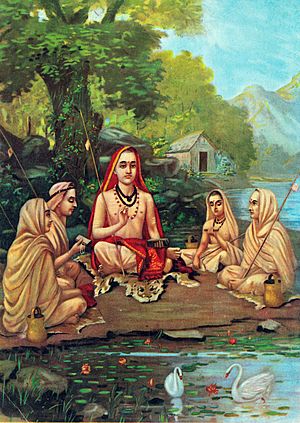

Orthodox Schools of Thought

Some of the oldest Indian philosophical texts are the Upanishads. These come from the later Vedic period (1000–500 BCE) and contain ideas from Brahmanism. Indian philosophies are often grouped based on their connection to the Vedas. Jainism and Buddhism started at the end of the Vedic period. Many traditions under Hinduism developed after this period.

Hindus usually divide Indian philosophies into 'orthodox' (āstika) or 'heterodox' (nāstika). This depends on whether they accept the authority of the Vedas and the ideas of brahman (ultimate reality) and ātman (the soul or self) found in them.

The schools that follow the ideas of the Upanishads are called "orthodox" or "Hindu" traditions. They are often grouped into six main philosophies, known as darśanas:

- Sānkhya

- Yoga

- Nyāya

- Vaisheshika

- Mimāmsā

- Vedānta

These six schools interpreted the Vedas and Upanishads in different ways, but they shared some common ground. They show that Hinduism allowed for many different philosophical ideas while still having a shared foundation.

Hindu thinkers from these six schools developed ways to understand knowledge (pramana). They also explored topics like:

- Metaphysics (the nature of reality)

- Ethics (moral principles)

- Psychology (the study of the mind)

- Hermeneutics (how to interpret texts)

- Soteriology (how to achieve salvation or liberation)

They did all this within the framework of Vedic knowledge, offering many different interpretations. These "Six Philosophies" (ṣaḍ-darśana) were the main competing ideas in what is called the "Hindu synthesis" of classical Hinduism.

The Six Philosophies

- Sāṃkhya

* This philosophy sees the universe as having two separate realities: puruṣa (the conscious observer) and prakṛti (the observed reality, including mind and matter). * It teaches that liberation comes from understanding this difference and separating purusha from the impurities of prakriti. * This school has included both atheistic and some theistic (believing in a god) thinkers. It forms the basis for much of later Indian philosophy.

- Yoga

* This school is similar to Sāṃkhya and might even be a part of it. * It accepts the idea of a personal god and focuses on the practice of yoga to achieve liberation.

- Nyāya

* This philosophy focuses on logic and how we gain knowledge. * It accepts six ways of knowing things (pramanas): perception, inference, comparison, postulation, non-perception, and reliable testimony. * Nyāya supports a form of direct realism (that things exist as we perceive them) and a theory of substances.

- Vaiśeṣika

* This school is closely related to Nyāya. * It focused on the nature of substance and supported a theory of atoms. * Unlike Nyāya, it only accepts two ways of knowing: perception and inference.

- Pūrva-Mīmāṃsā

* This school focuses on interpreting the Vedas, especially the meaning of Vedic rituals.

- Vedānta (also called Uttara Mīmāṃsā)

* This school focuses on understanding the philosophy of the Upanishads. * It particularly looks at ideas about liberation and the nature of Atman (soul) and Brahman (ultimate reality).

These schools are sometimes grouped into three pairs: Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika, Sāṃkhya-Yoga, and Mīmāṃsā-Vedānta. Each tradition also had different branches and sub-schools. For example, Vedānta had sub-schools like Advaita (non-dualism) and Dvaita (dualism).

It's important to know that the terms "orthodox" (astika) and "heterodox" (nastika) are Western terms. They don't have deep roots in ancient Sanskrit texts.

Heterodox (Śramaṇic) Schools

Several Śramaṇic movements existed before the 6th century BCE. These movements influenced both the orthodox and heterodox traditions of Indian philosophy. The Śramaṇa movement led to many different beliefs. These ranged from accepting or denying the idea of a soul, to ideas about atomism, ethics, materialism, atheism, agnosticism, and fatalism. They also debated free will, extreme asceticism, family life, strict ahimsa (non-violence), and whether eating meat was allowed.

Important philosophies that came from the Śramaṇic movement include Jainism, early Buddhism, Charvaka, Ajñana, and Ājīvika.

Ajñana Philosophy

Ajñana was one of the "heterodox" schools of ancient Indian philosophy. It was an ancient school of radical skepticism. It was a Śramaṇa movement and a major rival to early Buddhism and Jainism. Ajñana thinkers believed it was impossible to gain knowledge about deep philosophical questions. They also thought that even if knowledge was possible, it was useless for achieving final liberation. They were like sophists who were good at arguing against ideas without offering their own positive beliefs.

Jain Philosophy

Jain philosophy is one of the oldest Indian philosophies that completely separates the body (matter) from the soul (consciousness). Jainism was revived and re-established by Mahavira, the last and 24th Tirthankara. He brought together and renewed the ideas of ancient Śramaṇic traditions, which were first taught by the first Jain tirthankara Rishabhanatha millions of years ago. Historians believe Mahavira lived around the same time as the Buddha in the 5th century BCE.

Jainism is a Śramaṇic religion and does not accept the authority of the Vedas. However, like other Indian religions, it shares core ideas such as:

- Karma

- Ethical living

- Rebirth

- Samsara

- Moksha (liberation)

Jainism strongly emphasizes asceticism (a simple, self-disciplined life), ahimsa (non-violence), and anekantavada (the idea that truth has many sides). These ideas are seen as ways to achieve spiritual freedom and influenced other Indian traditions. Jainism believes strongly in the individual nature of the soul and that each person is responsible for their own choices. It teaches that self-reliance and individual effort are key to liberation. According to Jain philosophy, the world (Saṃsāra) is full of hiṃsā (violence). Therefore, one should work hard to achieve Ratnatraya: right perception, right knowledge, and right conduct. These are essential for liberation.

Buddhist Philosophy

Buddhist philosophy began with the teachings of Siddhartha Gautama, also known as the Buddha or "awakened one." Buddhism is based on parts of the Śramaṇa movement, which was active in the first half of the 1st millennium BCE. However, its foundations also include new ideas not found or accepted by other Sramana movements. Buddhism and Hinduism influenced each other and shared many concepts. But Buddhism rejected the Vedic ideas of Brahman (ultimate reality) and Atman (soul, self) that are central to Hindu philosophies.

Buddhism shares many philosophical views with other Indian systems, such as:

- Belief in karma (cause-and-effect)

- Samsara (cyclic afterlife and rebirth)

- Dharma (ethics, duties, and values)

- The idea that all material things and the body are temporary

- The possibility of spiritual liberation (nirvana or moksha)

A major difference from Hindu and Jain philosophy is that Buddhism rejects the idea of an eternal soul (atman). Instead, it teaches anatta (non-Self).

After the Buddha's death, several competing philosophical systems called Abhidharma emerged. These tried to organize Buddhist philosophy. The Mahayana movement also arose (around 1st century BCE onwards) and brought new ideas and scriptures.

Main Buddhist Traditions in India

The main traditions of Buddhist philosophy in India (from 300 BCE to 1000 CE) were:

- The Mahāsāṃghika ("Great Community") tradition, which had many sub-schools (now extinct).

- The schools of the Sthavira ("Elders") tradition:

* Vaibhāṣika ("Commentators"): This was an Abhidharma tradition known for its "Great Commentary." They believed that "all exists," meaning they had a form of eternalism about time. They also supported direct realism and a theory of substances. * Sautrāntika ("Those who uphold the sutras"): This tradition focused on the Buddhist sutras rather than the Abhidharma. They disagreed with the Vaibhāṣika on several points, including their view of time. * Pudgalavāda ("Personalists"): Known for their idea of the "person" (pudgala), this school is now extinct. * Vibhajyavāda ("The Analysts"): A widespread tradition that reached Kashmir, South India, and Sri Lanka. Part of this school survives today as the Theravada tradition. They rejected the views of the Pudgalavāda and Vaibhāṣika, among others.

- The schools of the Mahāyāna ("Great Vehicle") tradition (which still influence Tibetan and East Asian Buddhism):

* Madhyamaka ("Middle way" or "Centrism"): Founded by Nagarjuna. This tradition focuses on the idea that all things are empty of any fixed essence or substance (svabhāva). * Yogācāra ("Yoga praxis"): An idealistic school that believed only consciousness exists.

- The Dignāga-Dharmakīrti tradition: An important school that focused on epistemology, or pramāṇa (ways of knowing).

Many of these philosophies spread to other regions like Central Asia and China. Even after Buddhism declined in India, some of these philosophical traditions continued to develop in Tibetan Buddhist, East Asian Buddhist, and Theravada Buddhist traditions.

Ājīvika Philosophy

The philosophy of Ājīvika was founded by Makkhali Gosala. It was a Śramaṇa movement and a major rival to early Buddhism and Jainism. Ājīvikas were organized renunciates who formed simple monastic communities and lived an ascetic lifestyle.

The original writings of the Ājīvika school are lost. Their ideas are known from mentions in other ancient Indian texts, especially those from Jainism and Buddhism, which often criticized the Ajivikas. The Ājīvika school is known for its Niyati doctrine of absolute determinism (fate). This idea states that there is no free will, and everything that has happened, is happening, and will happen is completely planned by cosmic principles. Ājīvika thinkers believed the karma doctrine was false. Ājīvikas were atheists and rejected the authority of the Vedas. However, they believed that every living being has an ātman (soul), which is a central idea in Hinduism and Jainism.

Charvaka Philosophy

Charvaka (Sanskrit: चार्वाक), also known as Lokāyata, is an ancient school of Indian materialism. Charvaka believes that direct perception, empiricism (knowledge from experience), and conditional inference are the only true ways to gain knowledge. It supports philosophical skepticism and rejects rituals and supernaturalism. It was a popular belief system in ancient India.

The name Charvaka might come from the Sanskrit root carv, meaning 'to chew'. This could hint at the philosophy's focus on enjoying life, like "eat, drink, and be merry."

Brihaspati is traditionally seen as the founder of Charvaka philosophy, though some scholars debate this. During the Hindu reformation period in the first millennium BCE, when Buddhism and Jainism were established, Charvaka philosophy was well-known and opposed by both religions. Most of Charvaka's original writings, the Barhaspatya sutras, are lost. Their teachings have been gathered from historical secondary texts, such as those found in shastras, sutras, and Indian epic poetry, as well as from dialogues of Gautama Buddha and Jain literature.

One important idea of Charvaka philosophy was its rejection of inference as a way to find true, universal knowledge or metaphysical truths. In other words, Charvaka believed that whenever you infer a truth from observations, you must accept that there might be doubt. Inferred knowledge is always conditional.

Comparing Indian Philosophies

Indian traditions had many different philosophies, often disagreeing with each other and with the orthodox Hindu schools. Their differences included:

- Whether every person has a soul (atman) or if there is no soul.

- Whether a simple, ascetic life or a hedonistic (pleasure-seeking) life was better.

- Whether rebirth exists or not.

| Ājīvika | Early Buddhism | Charvaka | Jainism | Orthodox schools of Indian philosophy (Non-Śramaṇic) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Karma | Denies | Affirms | Denies | Affirms | Affirms |

| Samsara, Rebirth | Affirms | Affirms | Denies | Affirms | Some school affirm, some not |

| Ascetic life | Affirms | Affirms | Denies | Affirms | Affirms as Sannyasa |

| Rituals, Bhakti | Affirms | Affirms, optional (Pali: Bhatti) |

Denies | Affirms, optional | Theistic school: Affirms, optional Others: Deny |

| Ahimsa and Vegetarianism | Affirms | Affirms, Unclear on meat as food |

Strongest proponent of non-violence; Vegetarianism to avoid violence against animals |

Affirms as highest virtue, but Just War affirmed Vegetarianism encouraged, but choice left to the Hindu |

|

| Free will | Denies | Affirms | Affirms | Affirms | Affirms |

| Maya | Affirms | Affirms (prapañca) |

Denies | Affirms | Affirms |

| Atman (Soul, Self) | Affirms | Denies | Denies | Affirms | Affirms |

| Creator god | Denies | Affirms | Denies | Denies | Theistic schools: Affirm Others: Deny |

| Epistemology (Pramana) |

Pratyakṣa, Anumāṇa, Śabda |

Pratyakṣa, Anumāṇa |

Pratyakṣa | Pratyakṣa, Anumāṇa, Śabda |

Various, Vaisheshika (two) to Vedanta (six): Pratyakṣa (perception), Anumāṇa (inference), Upamāṇa (comparison and analogy), Arthāpatti (postulation, derivation), Anupalabdi (non-perception, negative/cognitive proof), Śabda (Reliable testimony) |

| Epistemic authority | Denies: Vedas | Affirms: Buddha text Denies: Vedas |

Denies: Vedas | Affirms: Jain Agamas Denies: Vedas |

Affirm: Vedas and Upanishads, Affirm: other texts |

| Salvation (Soteriology) |

Samsdrasuddhi | Nirvana (realize Śūnyatā) |

Siddha, Nirvana |

Moksha, Nirvana, Kaivalya Advaita, Yoga, others: Jivanmukti Dvaita, theistic: Videhamukti |

|

| Metaphysics (Ultimate Reality) |

Śūnyatā | Anekāntavāda |

Brahman |

Political Philosophy in India

The Arthashastra, believed to be written by the Mauryan minister Chanakya, is one of the earliest Indian texts about political philosophy. It dates back to the 4th century BCE and discusses ideas about how to govern a state and economic policies.

The political philosophy most linked to modern India is ahimsa (non-violence) and Satyagraha. Mahatma Gandhi made these ideas famous during the Indian struggle for independence. These ideas later influenced other independence and Civil Rights movements, especially those led by Martin Luther King Jr. and Nelson Mandela.

Integral humanism was a set of ideas developed by Upadhyaya as a political plan. It was adopted in 1965 as the official doctrine of the Jan Sangh party. Upadhyaya believed it was very important for India to create its own economic model that focused on human beings. This approach made it different from Socialism and Capitalism.

Influence of Indian Philosophy

Many thinkers have been impressed by Indian philosophy. T. S. Eliot, a famous writer, once said that the great philosophers of India "make most of the great European philosophers look like schoolboys." Arthur Schopenhauer, a German philosopher, used Indian philosophy to improve his own ideas. He wrote that anyone who has learned from "the sacred primitive Indian wisdom" is best prepared to understand his work. The 19th-century American philosophical movement called Transcendentalism was also influenced by Indian thought.

See also

In Spanish: Filosofía india para niños

In Spanish: Filosofía india para niños

- Ancient Indian philosophy

- Hindu philosophy

- Indian art

- Indian logic

- Indian psychology

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |