Buddhist philosophy facts for kids

Buddhist philosophy refers to the thinking and ideas that grew out of the teachings of Buddhism. It started in ancient India with Gautama Buddha around the 5th century BCE. Over many centuries, these ideas spread across Asia and developed into different schools of thought.

Buddhist philosophy is not just about thinking; it also involves practices like meditation. It explores big questions about life, suffering, and happiness. Buddhist thinkers have studied many topics, including ethics (how to live a good life), how the mind works, and how we can achieve peace.

The main goal of Buddhist philosophy is to find a way to end suffering and reach a state of lasting peace called Nirvana. Early Buddhists believed that people should not just accept teachings on faith. Instead, they should use reason and their own experience to understand them. The Buddha encouraged his followers to ask questions and investigate his teachings for themselves.

Contents

How Buddhist Ideas Developed

After the Buddha's life, his followers worked to preserve and understand his teachings. This led to different interpretations and the creation of various schools of Buddhism.

- Early Buddhism: The first teachings were passed down by word of mouth. They focused on core ideas like the Four Noble Truths and the Noble Eightfold Path.

- Scholastic Period: Later, scholars began to organize the teachings into detailed systems called Abhidharma. They created lists and categories to explain how the mind and reality work.

- Mahāyāna Buddhism: Starting around the 1st century CE, a new movement called Mahāyāna (meaning "Great Vehicle") emerged. It introduced new ideas, such as the path of the bodhisattva—an enlightened being who stays in the world to help others.

The Buddha's Core Teachings

The Buddha's teachings focus on understanding and overcoming suffering to achieve enlightenment, or bodhi. The ultimate goal is Nirvāṇa, a state of complete peace and freedom from the cycle of rebirth (saṃsāra).

The Middle Way

The Buddha called his teaching the "Middle Way". He saw that some people tried to find happiness through extreme pleasure, while others practiced extreme self-denial, like fasting for long periods. The Buddha taught that neither of these extremes leads to true peace. Instead, he recommended a balanced path that avoids both indulgence and harshness.

The Four Noble Truths

The Four Noble Truths are a key part of the Buddha's teachings. They are like a doctor's diagnosis and treatment plan for suffering:

- The Truth of Suffering (Duḥkha): Life always involves some form of dissatisfaction or suffering. This includes physical pain, sadness, and the stress of things always changing.

- The Truth of the Cause of Suffering: Suffering is caused by craving, desire, and ignorance. We suffer because we want things to be different than they are.

- The Truth of the End of Suffering: It is possible to end suffering by removing its causes—craving and ignorance.

- The Truth of the Path: The way to end suffering is to follow the Noble Eightfold Path. This path includes right understanding, right intention, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration.

The Idea of Non-Self (Anattā)

| The Five Aggregates (pañca khandha) according to the Pali Canon. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

→ ← ← |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source: MN 109 (Thanissaro, 2001) | diagram details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

One of the most important Buddhist ideas is Anattā, or "non-self". The Buddha taught that there is no permanent, unchanging "self" or "soul" inside of us. This was different from other Indian beliefs at the time, which taught about an eternal soul called ātman.

The Buddha explained that a person is made up of five changing parts, called the five aggregates:

- Form (our body)

- Feelings (pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral)

- Perceptions (how we recognize things)

- Mental formations (our thoughts and intentions)

- Consciousness (our awareness)

These parts are always in flux, like a flowing river. There is no single part that stays the same and makes you "you". The Buddha used the analogy of a chariot. A "chariot" is just a name we give to a collection of parts (wheels, axle, frame). If you take the parts away, there is no "chariot" left. In the same way, a "person" is a convenient name for the five changing aggregates. Believing in a permanent self, he taught, leads to attachment and suffering.

Karma and Rebirth

Buddhism teaches about karma and rebirth. Karma means "action" and refers to our intentional actions of body, speech, and mind. Good actions, like kindness and generosity, lead to positive results and happiness. Harmful actions, like lying or hurting others, lead to negative results and suffering. This cycle of action and result continues through many lives in a process called saṃsāra (the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth). The goal of Buddhism is to break free from this cycle and attain Nirvana.

Mapping the Mind: The Abhidharma

After the Buddha, different schools of thought emerged. Many of these schools developed a system called Abhidharma, which means "higher teaching". The Abhidharma project was an attempt to create a detailed map of reality.

Abhidharma scholars analyzed everything in existence, breaking it down into the smallest possible moments or events, which they called dharmas. They believed that everything we experience, from a flash of light to a feeling of joy, is made up of these tiny, interconnected dharmas. They thought that understanding this complex web of causes and effects was the ultimate truth about how things really are.

Different schools had different ideas. For example, the Sarvāstivāda school believed that dharmas exist in the past, present, and future. The Theravada school, which is common in countries like Sri Lanka and Thailand, argued that dharmas only exist in the present moment.

The Great Vehicle: Mahāyāna Buddhism

Around the 1st century BCE, a new movement called Mahāyāna ("Great Vehicle") began to grow. Mahāyāna philosophy built on earlier ideas but also introduced new concepts. A central figure in Mahāyāna is the bodhisattva, an enlightened person who chooses to delay their own Nirvana out of compassion to help all other beings become free from suffering.

Madhyamaka and Emptiness

The philosopher Nāgārjuna (c. 150–250 CE) founded the Madhyamaka ("Middle Way") school. His most important teaching was about shunyata, or "emptiness".

This doesn't mean that nothing exists. Instead, it means that things are "empty" of a permanent, independent self or essence. Everything arises depending on other things. For example, a table exists because of wood, a carpenter, nails, and so on. It is not a "table" all by itself. Nāgārjuna taught that understanding this deep interconnectedness of all things is the key to wisdom.

Yogācāra: The Mind-Only School

Another major Mahāyāna school is Yogācāra, which is sometimes called the "Mind-Only" school. Thinkers like Vasubandhu (4th century CE) argued that what we experience as the outside world is actually a projection of our own mind.

They used the example of a dream. In a dream, you can experience a whole world with people, places, and events, but it is all happening within your mind. Yogācāra philosophers suggested that our waking life is similar. By understanding that our reality is shaped by our consciousness, we can change our minds and free ourselves from suffering.

Vajrayāna: The Diamond Vehicle

Vajrayāna ("Diamond Vehicle") is a form of Mahāyāna Buddhism that became popular in India around the 8th century. It is also known as Tantric Buddhism and is the main form of Buddhism in Tibet.

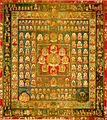

Vajrayāna is considered a faster path to enlightenment. It uses powerful techniques like chanting secret mantras, complex visualizations of deities and mandalas, and special forms of yoga. The goal is to transform negative emotions and experiences into wisdom.

Some Vajrayāna texts used shocking language, sometimes describing actions that were forbidden in mainstream Buddhism. Philosophers explained that this language was symbolic and not meant to be taken literally. For example, a text might say to "kill living beings," but this was interpreted as a metaphor for "stopping the flow of breath" during advanced meditation. These teachings were meant to help practitioners break free from ordinary ways of thinking.

Buddhism Spreads Across Asia

Buddhist philosophy continued to develop as it spread from India to other parts of Asia, like Tibet, China, and Japan.

Tibetan Buddhism

Tibetan Buddhist philosophy is based on the Indian Mahāyāna traditions. Philosophical debate is a very important part of training for monks in Tibet. Great thinkers like Śāntarakṣita helped bring Buddhism to Tibet in the 8th century. Over time, different schools like Nyingma, Kagyu, Sakya, and Gelug developed, each with its own unique philosophical views. The Gelug school, led by the Dalai Lama, became the most prominent.

Chinese and Japanese Buddhism

When Buddhism arrived in China, new schools emerged that blended Indian ideas with Chinese culture.

- The Tiantai school taught that all things are interconnected. It saw every single moment of experience as a reflection of the entire universe.

- The Huayan school used the metaphor of Indra's net. Imagine a vast net with a jewel at each knot. Each jewel reflects all the other jewels in the net, and each reflection also contains all the other reflections. This illustrates how all things contain and reflect each other.

- Chan (known as Zen in Japan) became very popular. Zen philosophy emphasizes meditation and direct experience of enlightenment over studying texts. The famous Zen master Dogen (1200–1253) wrote many important philosophical works in Japan.

Buddhist Philosophy in the Modern World

Today, Buddhist thinkers continue to explore and adapt these ancient ideas for the modern world. Many are interested in the connections between Buddhist philosophy and modern science, psychology, and social issues.

- In Asia, thinkers like Taixu in China and Buddhadasa in Thailand promoted a form of "Engaged Buddhism" that focuses on solving social problems.

- The 14th Dalai Lama has had many discussions with scientists about the nature of the mind and reality.

- The Vietnamese Zen master Thích Nhất Hạnh taught about "mindfulness," the practice of paying attention to the present moment, which has become popular worldwide.

- In the West, philosophers and scholars study Buddhist ideas in universities and compare them with Western philosophy. They explore how Buddhist concepts can help with issues like environmentalism and personal well-being.

Images for kids

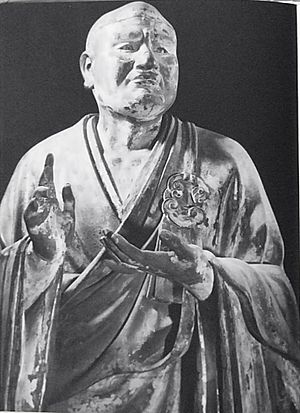

-

Buddhaghosa (c. 5th century), an important Abhidharma scholar of Theravāda Buddhism.

-

Site of Vikramaśīla university in Bihar, India, an important center for later Buddhist philosophy.

-

A 15th-century painting of Tsongkhapa, founder of the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism.

-

The Garbhadhatu mandala. The center square represents the young stage of Vairocana Buddha.

See also

In Spanish: Filosofía budista para niños

In Spanish: Filosofía budista para niños

- Abhidharma

- Buddhism and psychology

- Buddhism and science

- Buddhist logic

- Buddhist texts

- Enlightenment in Buddhism

- Buddhahood

- Buddhist paths to liberation

- Two truths doctrine

- Glossary of Buddhism

- Mindfulness

- Reality in Buddhism

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |