Śāntarakṣita facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Śāntarakṣita |

|

|---|---|

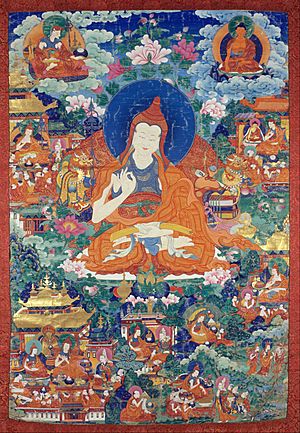

A painting from the 1800s showing parts of Shantarakshita's life.

|

|

| Religion | Mahayana Buddhism |

| Personal | |

| Born | Bhagalpur, Bihar |

Śāntarakṣita (pronounced Shaan-ta-rak-shee-ta) was a very important Indian Buddhist thinker. His name means "protected by the One who is at peace." He lived from about 725 to 788 CE. He was especially important for the start of Tibetan Buddhism.

Śāntarakṣita was a philosopher from the Madhyamaka school of thought. He studied at Nalanda University. He later founded Samye, which was the very first Buddhist monastery in Tibet.

He created a special way of thinking about Buddhism. It combined ideas from Madhyamaka, Yogācāra, and Buddhist logic. This new way of thinking is called Yogācāra-Mādhyamika in Tibetan Buddhism. Śāntarakṣita believed that some Yogācāra ideas, like "mind-only," were true on a basic, everyday level. This combination of ideas was a big step in Indian Buddhist philosophy.

Contents

Biography

We don't have many old records about Śāntarakṣita's life. Most of what we know comes from stories written by his followers. A scholar named Jamgon Ju Mipham Gyatso wrote about him in the 1800s. He used older books like the Blue Annals.

According to these stories, Śāntarakṣita was the son of a king from a place called Zahor. This area is now in the Bihar region of India. He was a Buddhist monk in the Pala Empire. He became the head of Nalanda University. This was after he became a master of many different subjects.

The king of Tibet, Trisong Detsen, invited him to Tibet around 763 CE. The king wanted him to help bring Buddhism to Tibet. But his first trip didn't go well. Tibetan stories say local spirits caused problems. So, he had to leave Tibet. He then stayed in Nepal for six years.

Later, Śāntarakṣita returned to Tibet. He came with a special teacher named Padmasambhava. Padmasambhava performed rituals to calm the spirits. This allowed the first Buddhist monastery in Tibet to be built. Śāntarakṣita then supervised the building of Samye monastery. It started in 775 CE. Samye was built like the Indian monastery of Uddaṇḍapura.

Around 779 CE, he helped ordain the first seven Tibetan Buddhist monks. Twelve Indian monks helped him. He stayed at Samye as the abbot, or head monk, for the rest of his life. This was about thirteen years after the monastery was finished. At Samye, Śāntarakṣita set up a Buddhist learning plan. It was based on Indian schools. He also oversaw the translation of Buddhist texts into Tibetan. Many other Indian scholars came to Tibet to help with this work. Tibetan stories say he died suddenly after a horse kicked him.

Philosophy and Teachings

Tibetan sources say Śāntarakṣita and his students taught basic Buddhist ideas. These included the "ten good actions" and the "six paramitas" (special virtues). They also taught about "dependent origination." This is the idea that everything comes from other things.

He and his student Kamalaśīla taught a "gradual path" to becoming a Buddha. This means you learn and grow step by step. Śāntarakṣita is famous for mixing different Buddhist ideas. He combined Madhyamaka philosophy with Yogācāra and Dharmakirti's logic.

His main ideas are in his book Madhyamakālaṃkāra. This means The Ornament of the Middle Way. He also wrote a commentary on it. Śāntarakṣita was not the first to mix these ideas. But he is seen as the most important teacher of this approach.

Two Truths

Like other Madhyamaka thinkers, Śāntarakṣita used the idea of "two truths". These are the ultimate truth and the conventional truth.

- Ultimate truth: In the deepest sense, all things are "empty". This means they don't have a fixed, unchanging nature.

- Conventional truth: On an everyday level, things do exist. They have a basic, temporary existence.

James Blumenthal explains Śāntarakṣita's view simply. He says Śāntarakṣita used Madhyamaka for ultimate truths. He used Yogācāra for conventional truths.

Śāntarakṣita also thought it was important to study "lower" Buddhist schools. He saw them as steps to understanding the highest Madhyamaka view. This way of organizing Buddhist ideas is still important in Tibet today.

Ultimate Truth: Neither One Nor Many

Śāntarakṣita believed that ultimate truth is the emptiness of all things. This means they lack a true, fixed nature. He used the "neither-one-nor-many argument" to show this.

The main idea is that nothing can have a true nature. Why? Because it can't be proven to exist as just one thing. And it can't be proven to exist as many separate things either. It's like a reflection in a mirror. It seems real, but it's not truly there.

In his book, Śāntarakṣita looked at many ideas from different schools. He showed that they couldn't be just one thing or many things. For example, he looked at the idea of a "Fundamental Nature" from the Sāṃkhya school. He argued it couldn't be truly one. This is because it creates many different effects over time.

He also used these arguments against some Buddhist ideas. He critiqued ideas about atoms, persons, space, and nirvana. He said that even consciousness cannot be truly one or many. So, like other Madhyamaka thinkers, he saw consciousness as empty of a fixed nature.

Since things can't be truly one, they also can't be truly many. This is because many things would depend on single things. Since single things don't truly exist, neither can many things. This means nothing has a true, fixed nature.

The Conventional Truth

All Madhyamaka thinkers agree that nothing has a permanent, fixed nature. But they have different ideas about conventional truth. This is how things "exist" in an everyday way.

Śāntarakṣita said that conventional things are those that:

- Are known by a mind.

- Can do things (they have an effect).

- Are always changing (they are impermanent).

- Cannot be found when you look for their ultimate nature.

Conventional truths are also described as being known by our thoughts. They are named based on how people use them in the world.

Śāntarakṣita also used ideas from the Yogācāra school for conventional truth. He said that conventional things are just consciousness. He also used the idea of "self-cognizing consciousness." This means our mind can know itself. So, Śāntarakṣita used Yogācāra ideas to understand everyday reality. He saw it as a step towards understanding the deeper truth of emptiness.

Works

Śāntarakṣita wrote about 11 books. Some of them are still around in Tibetan or Sanskrit. Some are even found in Jain libraries. This shows that even his opponents respected his work.

His most important books include:

- *Aṣṭatathāgatastotra: A short praise.

- *Śrīva-jradharasaṅgītibhagavatstotraṭīkā: Another short praise.

- Saṅvaraviṃśakavṛtti: This book talks about how a bodhisattva (a person on the path to Buddhahood) trains.

- Satyadvayavibhaṅgapañjikā: A long commentary on another text.

- Tattvasaṅgraha: A very large book that looks at many Indian philosophies.

- Madhyamakālaṅkāra: His main book explaining his ideas. He also wrote a commentary on it.

Tattvasaṅgraha

Śāntarakṣita's Tattvasaṅgraha means Compendium on Reality. It's a huge book with over 3,600 verses. It looks at many different Indian philosophies of his time.

In this book, Śāntarakṣita explains and then argues against many non-Buddhist ideas. He also discusses some Buddhist ideas. He explains and refutes ideas like a creator god, different theories of the self, and materialism.

A Sanskrit copy of this book was found in 1873. It was in a Jain temple in Jaisalmer. This copy also had a commentary by his student Kamalaśīla.

Madhyamakālaṅkāra

Śāntarakṣita's most famous book is the Madhyamakālaṅkāra (Ornament of the Middle Way). In this short book, he argues against some Hindu and Buddhist views. Then he explains his "two truths doctrine."

He says that Yogācāra ideas are the best way to understand conventional truth. But Madhyamaka's idea of emptiness is the ultimate truth. He summarized his approach at the end of the book: "If you understand that outside things don't exist, based on the idea of 'mind-only,' that's one step. Then, if you understand that even the mind itself has no fixed nature, that's another step. So, those who use logic and combine these two systems (Madhyamaka and Yogācāra) can become true Mahāyāna followers."

Influence

Śāntarakṣita had many important students in India. These included Kamalaśīla and Haribhadra. Other Indian scholars also followed his ideas.

His teachings were continued by Tibetan scholars like Ngok Lotsawa. Śāntarakṣita's work also influenced many later Tibetan figures. These include Sakya Pandita and Tsongkhapa.

Śāntarakṣita's philosophy was the main way of understanding Madhyamaka in Tibet for a long time. This was from the 700s until the 1100s and 1200s. Then, the work of Candrakirti started to be translated.

Later, Je Tsongkhapa (who lived from 1357-1419) created a new school called the Gelug. He strongly disagreed with some of Śāntarakṣita's ideas. Because of Tsongkhapa's efforts, Candrakirti's Madhyamaka became more popular in Tibet.

In the late 1800s, Ju Mipham tried to bring back Śāntarakṣita's ideas. This was part of the Rimé movement. This movement wanted to study different Buddhist traditions. Ju Mipham wrote the first commentary on Śāntarakṣita's Madhyamakālaṅkāra in almost 400 years.

Now, Madhyamakālaṅkāra is studied by all Nyingma students in their monastic colleges. It was almost forgotten before Ju Mipham.