Chan Buddhism facts for kids

Chan (pronounced "Chahn") is a type of Buddhism that started in China. It's a shorter way of saying "chánnà," which comes from the Sanskrit word dhyāna. This word means "meditation" or a deep, calm state of mind.

Chan Buddhism began in China around the 500s CE. It became super popular during the Tang dynasty and Song dynasty periods. You might know it better by its Japanese name, Zen Buddhism. Zen is just the Japanese way of saying the same Chinese word. Chan Buddhism also spread to other countries like Vietnam (where it's called Thiền) and Korea (where it's called Seon). In the 1200s, it traveled to Japan and became Japanese Zen.

Contents

- History of Chan

- Chan Spreads in Asia

- Chan in the Western World

- What Chan Teaches

- Teaching and Practice

- Chan Monasteries

- See also

- Images for kids

History of Chan

It's a bit tricky to know everything about early Chan history because some old records are missing. But we can still learn a lot!

Different Time Periods

The history of Chan in China can be split into a few main periods. The Zen we know today grew over a long time, changing quite a bit along the way. Each period had its own style of Zen.

Here's a simple way to look at it:

- The Legendary Period (around 400s to 700s CE): This is when famous figures like Bodhidharma and Huineng lived. Not many written records from this time exist. It's when the idea of the "Six Patriarchs" (important leaders) of Chan began.

- The Classical Period (around 700s to 900s CE): This was a time of great Chan masters like Mazu Daoyi and Linji Yixuan. Their teachings and sayings were written down, creating a new type of Buddhist literature.

- The Literary Period (around 900s to 1200s CE): During the Song dynasty, collections of gong'an (koans) were put together. These were stories or questions from famous masters, often with poems and comments. This period really shaped how people saw the "golden age" of Chan.

Buddhism Comes to China

Buddhism arrived in China centuries before Chan became a distinct school. When it first came, it mixed with Chinese culture, especially Taoism.

Buddhism Meets Chinese Culture

Imagine a new idea coming to your country and blending with your own traditions. That's what happened with Buddhism in China. Some scholars think Chan grew from a mix of Mahayana Buddhism and Taoism. Early Chinese Buddhists used Taoist words to explain Buddhist ideas. For example, the Buddha was sometimes seen as a wise person who achieved a Taoist-like state of "non-death."

Meditation was already practiced in China before Chan. Early Buddhist texts from India, which taught different types of meditation, were translated into Chinese. These included practices like focusing on breathing, thinking about the body, and practicing kindness.

Chinese thinkers like Sengzhao and Tao Sheng were influenced by Taoist ideas. They connected the Buddhist idea of "Buddha-nature" (the idea that everyone has the potential to become a Buddha) with the Taoist concept of "naturalness." This meant they believed Buddha-nature could be found in everyday life, just like the Tao.

Different Ways to Learn Buddhism

When Buddhism came to China, there were three main ways people trained:

- Virtue and Discipline: Following rules for monks and nuns.

- Meditation: Training the mind to be calm and clear.

- Teachings: Studying Buddhist texts and scriptures.

Because of this, different types of teachers appeared:

- Vinaya masters knew all the rules for monks and nuns.

- Dhyāna masters (like early Chan teachers) focused on meditation.

- Dharma masters were experts in Buddhist texts.

Chan monks often lived in monasteries that also taught other types of Buddhism. It wasn't always a completely separate "school" in China like it later became in Japan.

The First Chan Leaders (around 500s-700s CE)

The Chan tradition says that Chan started in India with the "Flower Sermon." The story goes that Gautama Buddha silently held up a flower, and only one disciple, Mahākāśyapa, understood its meaning and smiled. The Buddha then said he had passed on a special teaching "outside of scriptures" to Mahākāśyapa.

The Six Patriarchs

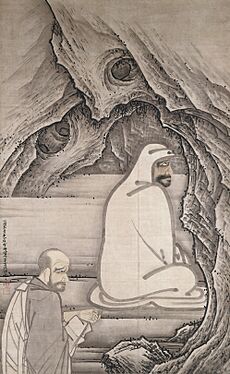

In China, the start of Chan is often linked to Bodhidharma. He was either from Central Asia or India and came to China around the 500s CE. The story of Bodhidharma and the "Six Patriarchs" (important leaders) of Chan was created later to give the growing Chan school more importance.

The traditional list of the first six Chan patriarchs in China is:

- Bodhidharma (around 440–528)

- Dazu Huike (487–593)

- Sengcan (?–606)

- Dayi Daoxin (580–651)

- Daman Hongren (601–674)

- Huineng (638–713)

Later on, this list was extended to include 28 Indian patriarchs before Bodhidharma.

Bodhidharma's Teachings

Bodhidharma is often shown as a bearded, wide-eyed person. He's sometimes called "The Blue-Eyed Barbarian" in old Chinese texts. He is said to have taught a "special transmission outside scriptures," meaning the true teaching wasn't just found in books.

One important text linked to Bodhidharma is the Long Scroll of the Treatise on the Two Entrances and Four Practices. It talks about two ways to reach enlightenment:

- Entrance of Principle: Understanding that all living things share the same "True Nature" (or Buddha-nature).

- Entrance of Practice: This involves four steps:

- Accepting suffering without complaint.

- Staying calm even when good things happen.

- Not craving things, as craving causes suffering.

- Following the Dharma (Buddhist teachings) without getting stuck on the idea of "practicing."

Huike and the Transmission

Bodhidharma chose his student, Dazu Huike, to follow him as the second patriarch. He supposedly passed on a robe, a bowl, and a copy of the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra to Huike as a symbol of this special teaching.

Early Chan in the Tang Dynasty (around 600s-900s CE)

With the fourth patriarch, Dayi Daoxin, Chan started to become a more organized school. He and the fifth patriarch, Daman Hongren, taught a new style called the "East Mountain Teaching." This teaching focused on "Maintaining the one without wavering," meaning focusing on the true nature of the mind, which is like Buddha-nature.

Instead of monks wandering alone, many students gathered at Hongren's home. This community-focused approach fit well with Chinese society.

Huineng and the Southern School

The sixth patriarch, Huineng, is a huge figure in Chan history. All later Chan schools look to him as their ancestor. The famous story says that Huineng, a simple woodcutter, won a contest to become the patriarch over a more learned monk. He then had to flee south to avoid angry rivals.

Modern scholars say this story was made popular later by Huineng's student, Shenhui, who wanted to show that Huineng's "Southern School" was the true line of Chan. Shenhui said that Huineng's teaching was about sudden enlightenment, while the "Northern School" taught gradual enlightenment. Even though both schools had elements of both, Shenhui's ideas made "sudden enlightenment" a key part of Chan.

The Platform Sutra, a very important Chan text, tells Huineng's story and became very popular. It also shows the growing importance of the Diamond Sutra in Chan.

Classical Chan – Tang Dynasty (around 750–1000 CE)

The later part of the Tang dynasty is often called the "golden age" of Chan. It was said that "The whole of [China] is the realm of the Chan school."

The Hongzhou School

One of the most important schools was the Hongzhou school of Mazu Daoyi. Famous masters like Linji Yixuan (who started the Rinzai school in Japan) came from this group.

This school was known for using "shock techniques" like shouting, beating, or giving strange answers to help students suddenly understand. These stories are still popular today. For example, a Chan teacher might hit a table with a stick during a talk to make a point.

A well-known story tells of Mazu's teacher, Nanyue Huairang, comparing seated meditation to polishing a tile. This wasn't against meditation itself, but against the idea of just doing a practice to "become a Buddha" as if it were a simple goal. Seated meditation remained important in Chan.

The Great Persecution

Around 845 CE, the emperor persecuted Buddhist schools in China. This was very hard on many Buddhist groups, but the Chan school of Mazu and his followers survived and became even more important.

Literary Chan – Song Dynasty (around 960–1300 CE)

During the Song dynasty, the government supported Chan, and it became the biggest Buddhist group in China. This period created the "ideal" image of Chan from the Tang dynasty.

The Five Houses of Chan

During the Song dynasty, five main "houses" or styles of Chan were recognized. These were based on different family trees of Chan teachers:

- Guiyang school

- Linji school

- Caodong school

- Yunmen school

- Fayan school

Rise of the Linji School

The Linji school became the most powerful, partly because it had support from scholars and the government. Its founder, Linji Yixuan, became known as the classic "iconoclastic" (meaning someone who challenges traditions) Chan master.

Koan Practice

The teachings of the old masters were written down in "encounter dialogues." These short stories were collected into texts like the Blue Cliff Record and The Gateless Gate. These became famous gōng'àn (koan) cases.

A koan is a story or conversation, usually from old Chan masters. They are used to test a student's progress. Koans often seem confusing or illogical, but for Chan Buddhists, a koan is a moment where truth reveals itself without the limits of language. To answer a koan, a student needs to let go of normal thinking and let understanding come naturally.

Silent Illumination

The Caodong school, another important Chan group, focused on "silent illumination," which means "just sitting" in meditation. This was different from the Linji school's focus on koans.

Chan After the Song Dynasty (1300s–Present)

After the Song dynasty, Chan continued to develop. It often mixed with other Buddhist traditions like Pure Land Buddhism, which focuses on chanting the name of a Buddha to be reborn in a Pure Land.

Modern Times

In the 1900s, Chan Buddhism saw a revival in China, especially with teachers like Hsu Yun. Many Chan teachers today trace their lineage back to him. These teachers, like Sheng Yen and Hsuan Hua, helped spread Chan to the Western world.

In Taiwan, several Chinese Buddhist teachers settled after the Communist Revolution in China. Four famous masters, known as the "Four Heavenly Kings" of Taiwanese Buddhism, founded large organizations that promote Chan and other Buddhist practices. These include:

- Sheng Yen, who founded Dharma Drum Mountain.

- Wei Chueh, who founded Chung Tai Shan.

- Cheng Yen, a nun who founded the Tzu Chi Foundation, a charity organization.

- Hsing Yun, who founded Fo Guang Shan, an international Buddhist movement.

Chan was suppressed in China for a while, but it's now growing again on the mainland, as well as in Taiwan and Hong Kong. Old temples are being rebuilt, and new Buddhist academies are opening.

Chan Spreads in Asia

Chan Buddhism didn't just stay in China; it traveled across Asia.

Thiền in Vietnam

According to tradition, an Indian monk named Vinītaruci brought Thiền (Vietnamese Chan) to Vietnam in the late 500s CE. Other Thiền schools also came from China, sometimes mixing with local practices.

Seon in Korea

Seon came to Korea between the 600s and 800s CE. A very important monk named Jinul (1158–1210) helped organize Seon and introduced koan practice to Korea.

Zen in Japan

Zen didn't arrive as a separate school in Japan until the 1100s.

- Eisai traveled to China and brought back the Linji lineage, which became the Rinzai school in Japan.

- Later, Dōgen went to China and learned from a Caodong master. He then started the Sōtō school in Japan.

Today, the main Zen schools in Japan are Sōtō, Rinzai, and Ōbaku.

Chan in the Western World

Chan, especially in its Japanese Zen form, has become very popular in the West. People started to become seriously interested in Zen in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Western Chan Teachers

One of the first Chinese masters to teach Westerners in North America was Hsuan Hua in the 1960s. He founded the City Of Ten Thousand Buddhas, a large monastery and retreat center in California. Another important Chinese Chan teacher was Sheng Yen, who taught both Caodong and Linji styles. He founded meditation centers in New York.

What Chan Teaches

Even though Chan says it's a "special transmission outside scriptures" and "doesn't rely on words," it has a rich background of Buddhist teachings.

Key Ideas

Classical Chinese Chan often deals with pairs of ideas, like:

- Absolute and Relative: How ultimate reality is connected to our everyday world.

- Buddha-nature and Emptiness (śūnyatā): The idea that everyone has the potential for awakening, and that all things are "empty" of a fixed, separate self.

- Sudden and Gradual Enlightenment: Whether understanding happens all at once or over time.

Buddha-nature and Emptiness

When Buddhism came to China, the idea of Buddha-nature (that all living beings have the potential to become a Buddha) was popular. It seemed similar to the Taoist idea of the Tao, a deep reality underlying everything.

Śūnyatā (pronounced "shoon-yah-tah") means "emptiness." It teaches that while we see separate objects, if you look closely, they don't have a fixed, independent "thing-ness." The Heart sutra says, "form is emptiness, emptiness is form." This means that the world we see and the ultimate reality are not separate.

Chan teachers often talk about Buddha-nature, but they also stress that Buddha-nature is emptiness – meaning it's not a fixed, separate soul.

Sudden and Gradual Enlightenment

In Chan, there are two main ideas about how enlightenment happens:

- Sudden Enlightenment: This means having a sudden insight into your true nature.

- Gradual Enlightenment: This means a slow process of purification and cultivation after that initial insight.

The Platform Sutra tries to bring these two ideas together, saying that seeing your true nature is sudden, but then you need to gradually work on yourself to become a Buddha.

Chan Texts

Chan is deeply rooted in the teachings of Mahayana Buddhism. Chan emphasizes that the Buddha's enlightenment came from direct experience and meditation, not just from thinking. So, Chan believes that others can also reach enlightenment through practice and meditation.

Early Chan masters knew many Mahayana Buddhist texts. For example, Huineng in the Platform Sutra talks about the Diamond Sūtra, the Lotus Sutra, and others.

Over time, Chan also created its own important writings, especially the "encounter dialogue" texts that led to the kōan collections.

Teaching and Practice

Chan takes many of its basic ideas from Mahayana Buddhism, like the idea of the Bodhisattva. A Bodhisattva is someone who delays their own full enlightenment to help all other living beings. This shows the importance of Karuṇā (compassion).

Meditation is central to Chan practice. In the Linji (Rinzai) school, this is often combined with koan study.

Chan Meditation

Chan believes that too many ideas and words can hide the true wisdom of our Buddha-nature. So, Chan encourages people to look inward and not just trust what they read or are told.

Sitting Meditation

Sitting meditation is called zuòchán (pronounced "zwo-chan") in Chinese, or zazen in Japanese. It simply means "sitting meditation." During this practice, people usually sit in a lotus position or similar posture. To calm the mind, they might focus on counting their breaths or on their lower belly.

In the Song dynasty, koan practice became popular, while others focused on "silent illumination." These became different styles in the Linji and Caodong traditions.

Koan Practice

A koan is a story or conversation, usually from old Chan masters. They are used to test a student's progress. Koans often seem confusing or illogical, but for Chan Buddhists, a koan is a moment where truth reveals itself without the limits of language. To answer a koan, a student needs to let go of normal thinking and let understanding come naturally.

Chan Monasteries

Chan developed its own way of life in monasteries.

Focus on Daily Life

As Chan grew in China, the rules for monks became special. They focused on practicing Buddhism in all parts of daily life. Temples started to emphasize hard work and humility. This meant that monks did everyday tasks like gardening, carpentry, cleaning, and managing the monastery.

The famous Chinese Chan master Baizhang (720–814 CE) had a guiding principle: "A day without work is a day without food." This shows how important daily tasks became to Chan practice. This way of life was different from Indian Buddhist monks, who often wandered and begged for food. In China, the monks lived and worked together in communities. This meant that the enlightenment sought in Chan had to work well with the challenges of everyday life.

See also

- Blue Cliff Record

- Hua Tou

- Buddhism

- Outline of Buddhism

- Timeline of Buddhism

- List of Buddhists

- Chinese Buddhism

- Japanese Zen

- Yiduan

- Putong Temple

Images for kids

-

Bodhidharma with Dazu Huike. Painting by Sesshū Tōyō, 15th century.

-

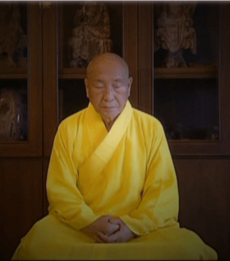

Avalokiteśvara sitting in meditation

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |