Huineng facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Dajian Huineng |

|

|---|---|

| Chinese: 惠能 | |

A very old preserved body, thought to be Huineng's

|

|

| Religion | Chan Buddhism |

| Temple | Guangxiao Temple Nanhua Temple |

| Dharma names | Huineng (惠能) |

| Posthumous name | Dajian (大鑒) |

| Personal | |

| Nationality | Chinese |

| Born | February 27, 638 Xinxing County, Guangdong, China |

| Died | 713 (aged 74–75) Guo'en Temple, Xinxing County, Guangdong, China |

| Religious career | |

| Teacher | Daman Hongren |

| Students | Qingyuan Xingsi Shitou Xiqian Nanyue Huairang |

| Works | Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch |

Dajian Huineng (born February 27, 638 – died August 28, 713) was a very important person in the early history of Chinese Chan Buddhism. Chan Buddhism is a type of Buddhism that focuses on meditation and reaching a sudden understanding of the world. Huineng is often called the Sixth Patriarch or Sixth Ancestor of Chan.

The stories say that Huineng was not formally educated. However, he supposedly had a sudden moment of understanding when he heard someone reading from a Buddhist book called the Diamond Sutra. Even though he didn't have much training, he showed his deep understanding to the Fifth Patriarch, a wise teacher named Daman Hongren.

Hongren then chose Huineng to be his true successor. This was a surprise because another student, Yuquan Shenxiu, was expected to be chosen. Later, some scholars thought that parts of Huineng's story might have been made up by a monk named Heze Shenhui. Shenhui claimed to be one of Huineng's students.

Huineng is seen as the founder of the "Sudden Enlightenment" school of Chan Buddhism. This teaching focuses on getting a quick and direct understanding of Buddhist wisdom. The Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch is a very important book in East Asian Buddhism. It is believed to contain Huineng's teachings.

Contents

Biography

How We Know About Huineng

The main stories about Huineng's life come from two old texts. These are the introduction to the Platform Sutra and a book called the Transmission of the Lamp.

Many modern experts believe that the traditional stories about Huineng might not be completely true. They think he was a real person, but that his life story became a legend over time. This legend grew in the century after he died. It shows how Buddhist ideas changed and developed.

The Platform Sutra

The Platform Sūtra of the Sixth Patriarch is said to be written by Fahai, one of Huineng's students. It tells about Huineng's life, his talks, and his discussions with students. However, the book seems to have been put together over a long time. It might contain different layers of writing from various periods.

The Platform Sutra mentions and explains many other important Buddhist scriptures. Some of these include the Diamond Sutra, Lotus Sutra, and Vimalakirti Sutra.

Huineng's Early Life

Huineng's own story in the Platform Sutra says his father was from Fanyang. His father lost his government job and died when Huineng was young. Huineng and his mother were very poor. They moved to Nanhai, where Huineng sold firewood to support his family.

One day, Huineng was delivering firewood. He heard a man reciting the Diamond Sutra. Huineng said, "When I heard the words of the scripture, my mind opened up and I understood." He asked why the man was chanting this book. The man told him about the Fifth Patriarch of Chan, who lived in a monastery in Huangmei District. The man gave Huineng some money and suggested he go meet the Fifth Patriarch.

Meeting the Fifth Patriarch

Huineng traveled for thirty days and finally reached Huangmei. He told the Fifth Patriarch, Hongren, that he wanted to become a Buddha. Hongren noticed that Huineng was from Guangdong and looked different from the local people. He called Huineng a "barbarian from the south" and doubted if he could reach enlightenment.

But Huineng impressed Hongren. He showed a clear understanding that everyone has a Buddha nature inside them. Hongren then allowed Huineng to stay at the monastery. Huineng was told to work in the backyard, splitting firewood and pounding rice. He was asked to avoid the main hall where the other monks studied.

The Poem Contest

Eight months later, the Fifth Patriarch gathered all his students. He announced a poem contest. The goal was for students to show how well they understood the true nature of the mind. Hongren said he would give his special robe and teachings to the winner. That person would become the Sixth Patriarch.

Shenxiu, who was the top student, wrote a poem. But he was too scared to show it directly to the master. So, one night, he wrote his poem on a wall in the south corridor, hoping to stay anonymous. Other monks saw it and praised it. Shenxiu's poem said:

The body is the bodhi tree.

The mind is like a bright mirror's stand.

At all times we must strive to polish it

and must not let dust collect.

The Patriarch was not fully happy with Shenxiu's poem. He said it didn't show a deep understanding of one's "fundamental nature." He gave Shenxiu another chance to write a better poem. But Shenxiu was too worried and couldn't write anything else.

Two days later, Huineng, who couldn't read, heard a young helper chanting Shenxiu's poem. He asked about it. The helper explained the contest and the idea of passing down the robe and teachings. Huineng asked to be taken to the corridor to see the poem. He then asked a local official named Zhang Riyong to read the poem to him. After hearing it, Huineng immediately asked the official to write down a poem that he composed.

The earliest versions of the Platform Sutra show two different poems by Huineng. Later versions usually have one main poem. Here are some versions:

Bodhi originally has no tree.

The mirror has no stand.

The Buddha-nature is always clear and pure.

Where is there room for dust?The mind is the bodhi tree.

The body is the bright mirror's stand.

The bright mirror is originally clear and pure.

Where could there be any dust?Bodhi originally has no tree.

The bright mirror also has no stand.

Fundamentally there is not a single thing.

Where could dust arise?

The other monks were amazed that a "southern barbarian" could write such a poem. But to protect Huineng, the Patriarch wiped away the poem. He said that the person who wrote it had not yet reached enlightenment.

Huineng Becomes the Sixth Patriarch

However, the next day, the Patriarch secretly went to Huineng's room. He asked, "Is the rice ready?" Huineng replied that the rice was ready and just needed to be sifted. The Patriarch then secretly explained the Diamond Sutra to Huineng. When Huineng heard the words "one should activate one’s mind so it has no attachment," he had a "sudden and complete enlightenment." He understood that everything exists within one's own true nature.

That night, the Dharma (Buddhist teachings) was passed to Huineng. The Patriarch gave him "the doctrine of sudden enlightenment" along with his robe and bowl. He told Huineng, “You are now the Sixth Patriarch. Take care of yourself, help as many living beings as you can, and spread the teachings so they will not be lost.”

Escape from the Monastery

Hongren also told Huineng that the Dharma was passed from mind to mind. The robe, however, was a physical symbol passed from one patriarch to the next. Hongren told Huineng to leave the monastery quickly before anyone could harm him. He even showed Huineng the way to escape and rowed him across a river. Huineng understood Hongren's actions. He showed that he could "ferry to the other shore" (reach enlightenment) with the teachings he had received.

Within two months, the Sixth Patriarch reached the Tayu Mountains. He realized that hundreds of men were following him. They wanted to steal the robe and bowl. One man named Huiming tried to take them, but the robe and bowl would not move. Huiming then asked Huineng to teach him the Dharma. Huineng helped him reach enlightenment and continued his journey.

Teachings

Sudden Enlightenment

Huineng's "Southern School" of Chan Buddhism taught that enlightenment is sudden. This means understanding comes all at once, like a flash. Another group, the "Northern School," taught that enlightenment was a gradual process.

While these ideas were debated, both schools came from the same traditions. Huineng's ideas became very important. Eventually, all later Chan schools looked back to Huineng as their origin. "Sudden enlightenment" became a main teaching in Chan Buddhism.

"No-Thought" and Meditation

Huineng taught about "no-thought." This means having a "pure and unattached mind" that can "come and go freely." It doesn't mean you stop thinking completely. Instead, it's about being very aware but not getting stuck on thoughts. It's an open, clear state of mind that lets you experience reality directly, just as it is.

Huineng's Impact on History

Some modern historians believe that Huineng was not very well-known during his lifetime. They think his amazing life story was created later, around the mid-700s. A monk named Shenhui, who claimed to be Huineng's student, might have helped create this story. He did this to gain more influence in the Imperial Court.

Shenhui's ideas became very popular. In 796, an important group decided that Huineng's "Southern line" of Chan was the true way. They even put up a special inscription saying Shenhui was the seventh patriarch.

The story of Huineng in the Platform Sutra is a powerful legend. It tells of an uneducated person who became a great leader of Chan Buddhism. Most of what we know about Huineng comes from this book. It is like a biography of a saint, showing him as a hero. This story was written to give authority to Huineng's teachings. The Sutra became very popular and was shared widely. This helped make Huineng's lineage more important.

It seems that not much was known about Huineng before Shenhui started telling his story. Shenhui used his skills to make Huineng a famous figure. The Platform Sutra likely includes many ideas that Shenhui created. After Huineng died, Shenhui wanted to be seen as the main authority in Chan Buddhism. He faced challenges from other monks. It's likely that Shenhui used this autobiography to connect himself to the most famous figures in Zen Buddhism, linking him all the way back to the Buddha.

An old inscription about Huineng, written by the famous poet Wang Wei, also shows some differences from Shenhui's story. This inscription doesn't criticize the "Northern Chan" group. It also adds new information about a monk named Yinzong, who is said to have helped Huineng become a monk. Wang Wei was a respected poet and government official. Shenhui, on the other hand, was more of a public speaker. This makes some people question how accurate Shenhui's stories were.

It seems that Shenhui didn't have much reliable information about Huineng. He knew Huineng was a student of Hongren and lived in a certain area. He also knew that some Chan followers saw Huineng as a teacher of only regional importance. It looks like Shenhui created the famous figure of Huineng. He did this so he could become the "true heir" of the Buddhist teachings, tracing a direct line from the Buddha. This seemed to be the only way he could achieve such a high position.

Chan Buddhist practices, like silent teaching and sudden enlightenment, were quite different from how monks usually trained. Old Chan stories often made fun of the traditional idea of a scholar-monk.

Mummification

There is a preserved body, believed to be Huineng's, kept at Nanhua Temple in Shaoguan, China. A Jesuit priest named Matteo Ricci saw this body in 1589. Ricci told Europeans about Huineng's story, describing him as someone similar to a Christian holy person. Ricci called him Liùzǔ, which means "The Sixth Ancestor."

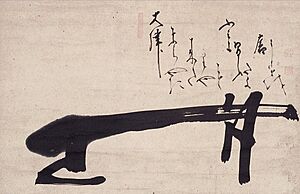

Liang Kai's Paintings of Huineng

The two paintings you see here were made by Liang Kai. He was a painter from the Southern Song dynasty. He left his job as a court painter to practice Chan Buddhism. These paintings show Huineng, the Sixth Patriarch of Chan Buddhism. In both paintings, Huineng is in the lower middle part. His face is turned to the side, so you can't see his exact features.

"The Sixth Patriarch Cutting the Bamboo" shows Huineng's journey to enlightenment. It highlights his focus and deep thought as he cuts bamboo. This specific moment of his enlightenment is only shown in this painting, not in any written stories. He holds an ax in his right hand and uses his left arm to steady a bamboo stalk. He looks closely at it. The painting uses loose and free brushstrokes. These create a simple but lively image. They suggest a gentle movement as he pulls the bamboo towards him. Huineng wears a shirt with rolled-up sleeves. Light and dark ink create shadows and contrast. A light shadow on his right arm and the bamboo suggests where the light is coming from.

"The Sixth Patriarch Tearing a Sutra" uses a similar style to show Huineng doing another everyday action. This painting also supports the idea of the Southern Chan Tradition. It emphasizes that you can reach sudden enlightenment without needing to train as a monk in the usual way or study many Buddhist books.

Film

- A Chinese movie called Legend of Dajian Huineng is based on Huineng's life. This film uses an older version of his story.

See also

In Spanish: Huineng para niños

In Spanish: Huineng para niños

- Hong Yi