Vedanta facts for kids

Vedanta (pronounced "veh-DAHN-tah") is an important Hindu philosophy. It's one of the six main traditional schools of Hindu thought. The word "Vedanta" means "the end of the Vedas" because its ideas come from the Upanishads, which are the final parts of the Vedas. Vedanta focuses on gaining knowledge and achieving spiritual freedom.

Over time, many different Vedanta traditions developed. But they all base their ideas on a common set of three important texts called the Prasthanatrayi (pronounced "pras-THAH-nah-TRAH-yee"). These are the Upanishads, the Brahma Sutras, and the Bhagavad Gita.

All Vedanta traditions talk a lot about:

- What exists? (like the nature of reality)

- How to find spiritual freedom?

- How do we know things? (how we get true knowledge)

Even though they discuss these same topics, the different schools of Vedanta have many disagreements. They might seem very different because of their unique ways of thinking.

Some of the main Vedanta traditions include:

- Bhedabheda (which means "difference and non-difference")

- Advaita (meaning "not two," or non-dualism)

- Vishishtadvaita (meaning "qualified non-dualism")

- Tattvavada (also known as Dvaita, meaning "dualism")

- Suddhadvaita (meaning "pure non-dualism")

- Achintya-Bheda-Abheda (meaning "inconceivable difference and non-difference")

Newer forms of Vedanta include Neo-Vedanta and the philosophy of the Swaminarayan Sampradaya.

Most major Vedanta schools, except for Advaita Vedanta and Neo-Vedanta, are connected to Vaishnavism. Vaishnavism focuses on devotion (Bhakti Yoga) to God, who is often seen as Vishnu or one of his forms (called an Avatar). Advaita Vedanta, however, emphasizes Jñana (knowledge) and Jñana Yoga more than devotion to a personal God. While Advaita's idea of oneness has become well-known in the West, most other Vedanta traditions focus on Vaishnava beliefs.

Contents

- What does "Vedanta" mean?

- Vedanta Philosophy

- Main Schools of Vedanta

- History of Vedanta

- Before the Brahma Sutras (before 5th century CE)

- The Brahma Sutras (completed in 5th century CE)

- Between the Brahma Sutras and Adi Shankara (5th–8th centuries)

- Gaudapada and Adi Shankara (Advaita Vedanta) (6th–9th centuries)

- Early Vaishnavism Vedanta (7th–9th centuries)

- Vaishnavism Bhakti Vedanta (11th–16th centuries)

- Modern Times (19th century – Present)

- Influence of Vedanta

- See also

What does "Vedanta" mean?

The word Vedanta is made of two Sanskrit words:

- Veda (वेद) — refers to the four sacred Vedic texts.

- Anta (अंत) — this word means "End."

So, Vedanta literally means "the end of the Vedas." It first referred to the Upanishads, which are the knowledge sections of the Vedas. Later, the meaning of Vedanta grew to include all the different philosophical traditions that are based on the Prasthanatrayi texts.

The Upanishads can be seen as the "end" of the Vedas in a few ways:

- They were the last writings from the Vedic period.

- They represent the highest point of Vedic philosophy.

- They were taught and discussed last, during the student stage of life (Brahmacharya).

Vedanta is one of the six traditional Hindu philosophy schools. It is also called Uttara Mīmāṃsā, which means "the later study" or "higher study." It's often compared to Pūrva Mīmāṃsā, which means "the earlier study." Pūrva Mīmāṃsā deals with the ritualistic parts of the Vedas, while Uttara Mīmāṃsā (Vedanta) looks at deeper questions about life and meaning.

Vedanta Philosophy

Even with their differences, all schools of Vedanta share some common ideas:

- Vedanta seeks to understand Brahman (the ultimate reality) and Ātman (the individual soul).

- The Upanishads, the Bhagavad Gita, and the Brahma Sutras are the core texts (known as the three main sources).

- Scripture (called Sruti Śabda) is the most reliable way to gain knowledge.

- Brahman (often seen as Ishvara, or God) is the unchanging cause of the world. (Dvaita Vedanta is an exception, seeing Brahman only as the efficient cause, not the material cause).

- The self (Ātman or Jiva) is responsible for its own actions (karma) and receives the results of these actions.

- They believe in rebirth (samsara) and the goal of being freed from this cycle (moksha).

- They generally do not agree with the ideas of Buddhism and Jainism, or some other Vedic schools.

Sacred Texts

The main Upanishads, the Bhagavad Gita, and the Brahma Sutras are the foundational scriptures in Vedanta. All Vedanta schools explain their philosophy by interpreting these texts, which are together called the Prasthanatrayi (meaning "three sources").

- The Upanishads, or Śruti prasthāna: These are considered the "heard" (and repeated) foundation of Vedanta.

- The Brahma Sūtras, or Nyaya prasthana: These are seen as the reason-based foundation of Vedanta.

- The Bhagavadgītā, or Smriti prasthāna: This is considered the "remembered tradition" foundation of Vedanta.

Important Vedanta teachers like Shankara, Ramanuja, and Madhva all wrote commentaries on these three texts. The Brahma Sūtras by Badarayana bring together the teachings from the many Upanishads. The Bhagavadgītā has also greatly influenced Vedanta thought.

All Vedantins agree that scripture (śruti) is the only way to know about spiritual matters that are beyond what we can see or figure out. As Rāmānuja explained, ideas based only on human thoughts can be disproven. So, for spiritual truths, scripture is the main authority.

For some Vedanta schools, other texts are also very important. For example, for Advaita Vedanta, the writings of Adi Shankara are key. For the Vaishnava schools, the Bhagavata Purana is especially important. Some teachers, like Vallabha, even added the Bhāgavata Purāṇa as a fourth main text to the Prasthānatrayī.

Understanding Reality

Vedanta philosophies discuss three main parts of reality and how they relate to each other:

- Brahman or Ishvara: This is the ultimate reality, the supreme truth.

- Ātman or Jivātman: This is the individual soul or self.

- Prakriti/Jagat: This is the changing physical world, including our bodies and matter.

Brahman / Ishvara – Ideas of the Supreme Reality

Shankara, who founded Advaita, talks about two ways to understand Brahman:

- Parā or Higher Brahman: This is Brahman without any qualities, beyond thought or words. It's the absolute reality.

- Aparā or Lower Brahman: This is Brahman with qualities, seen as the personal God who created the universe.

Ramanuja, who founded Vishishtadvaita, disagreed with the idea of a Brahman without qualities. He saw Brahman as Ishvara, a personal God with all good qualities. This God is both the ultimate reality and someone devotees can connect with.

Madhva, who founded Dvaita, believed that Vishnu is the supreme God. He saw Brahman as a personal God, similar to Ramanuja. Nimbarka and Vallabha also accepted Brahman as having both qualities and being beyond them, or as manifesting as a personal God, matter, and individual souls.

How Brahman and the Soul are Connected

The different Vedanta schools have different ideas about how the individual soul (Ātman / Jivātman) and the ultimate reality (Brahman / Ishvara) are connected:

- Advaita Vedanta: Believes Ātman is exactly the same as Brahman. There is no difference.

- Vishishtadvaita: Believes Jīvātman is different from Ishvara, but always connected to Him. They see the ultimate reality as a single, organized whole.

- Dvaita: Believes the Jīvātman is completely and always different from Brahman / Ishvara.

- Shuddhadvaita: Believes Jīvātman and Brahman are the same. Both, along with the changing universe, are seen as Krishna.

How We Know Things

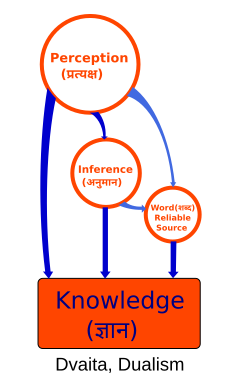

Pramāṇa (pronounced "prah-MAH-nah") means "proof" or "a way of valid knowledge." It's about how humans gain accurate and true knowledge. It focuses on how we know things and how much we can know. Ancient Indian texts list six main pramanas (ways of knowing):

- Pratyakṣa (perception, like seeing or hearing)

- Anumāṇa (inference, like figuring something out)

- Upamāṇa (comparison and analogy)

- Arthāpatti (postulation, figuring things out from circumstances)

- Anupalabdi (non-perception, like knowing something isn't there)

- Śabda (scriptural testimony or what reliable experts say)

Different Vedanta schools disagree on which of these six ways are truly valid. For example, Advaita Vedanta accepts all six pramanas. But Vishishtadvaita and Dvaita only accept three: perception, inference, and testimony.

Advaita considers Pratyakṣa (perception) as the most reliable source of knowledge. Śabda (scriptural evidence) is secondary, except for matters about Brahman, where it's the only evidence. In Vishishtadvaita and Dvaita, Śabda (scriptural testimony) is seen as the most important way to gain knowledge.

Ideas about Cause and Effect

All Vedanta schools believe in Satkāryavāda, which means that the effect already exists in its cause. However, they have different views on the "effect," meaning the world. Most Vedanta schools, like Samkhya, support Parinamavada. This idea says that the world is a real transformation of Brahman.

In contrast, Adi Shankara and Advaita Vedantists believe in Vivartavada. This view says that the world is just an unreal transformation of its cause, Brahman. It means that while Brahman seems to change, it doesn't actually change. The many things we see are not truly real, as only Brahman is truly real.

Main Schools of Vedanta

The Upanishads explore different ideas and argue for or against them. Vedanta schools interpret these texts and the Brahma Sutras to support their own specific views. Different interpretations led to the many Vedanta schools we know today.

While Advaita Vedanta is the most famous, many scholars suggest that the true heart of Vedanta lies within the Vaishnava tradition. In Vaishnava traditions, four main schools are very important. The number of prominent Vedanta schools can vary, with some scholars listing three to six.

Here are some of the main schools:

- Bhedabheda (difference and non-difference)

* Dvaitādvaita (Vaishnava), founded by Nimbarka (7th century CE) * Achintya Bheda Abheda (Vaishnava), founded by Chaitanya Mahaprabhu (1486–1534 CE)

- Advaita (monistic), with important teachers like Gaudapada (~500 CE) and Adi Shankaracharya (8th century CE)

- Vishishtadvaita (Vaishnava), with important teachers like Ramanuja (1017–1137 CE)

* Akshar-Purushottam Darshan, based on the teachings of Swaminarayan (1781-1830 CE)

- Tattvavada (Dvaita) (Vaishnava), founded by Madhvacharya (1199–1278 CE)

- Suddhadvaita (Vaishnava), founded by Vallabha (1479–1531 CE)

Bhedabheda Vedanta (Difference and Non-Difference)

Bhedābheda means "difference and non-difference." It's more of a tradition than a single school. Schools in this tradition believe that the individual self (Jīvatman) is both different from and not different from Brahman. Important figures include Nimbārka (who founded the Dvaitadvaita school) and Chaitanya Mahaprabhu (who founded the Achintya Bheda Abheda school).

Dvaitādvaita Vedanta

Nimbārka (7th century) taught Dvaitādvaita. This school sees Brahman (God), souls (chit), and matter (achit) as three equally real and eternal things. Brahman is the controller, the soul is the enjoyer, and the material world is what is enjoyed. Brahman is Krishna, the ultimate cause who knows and can do everything. He is the cause of the universe because He creates it so souls can experience the results of their actions. God is also the material cause because creation comes from His powers. He can be understood through meditation and devotion.

Achintya-Bheda-Abheda Vedanta

Chaitanya Mahaprabhu (1486 – 1533) was the main teacher of Achintya-Bheda-Abheda. In Sanskrit, achintya means 'inconceivable'. This philosophy means "inconceivable difference in non-difference." It relates to the ultimate reality of Brahman-Atman, which it calls Krishna. The idea of "inconceivability" helps explain seemingly opposite ideas in the Upanishads. This school says that Krishna is Bhagavan (God) for devotees and Brahman for those seeking knowledge. He has a divine power that is beyond our understanding. He is everywhere in the universe (non-difference), yet He is also much more (difference). This school is the basis of the Gaudiya Vaishnava tradition, which includes the ISKCON (Hare Krishnas).

Advaita Vedanta (Non-Dualism)

Advaita Vedanta (pronounced "Ad-VY-tah Veh-DAHN-tah"), taught by Gaudapada (7th century) and Adi Shankara (8th century), believes in non-dualism, meaning "not two." It says that Brahman is the only unchanging reality and is the same as the individual Atman (soul). The physical world, however, is always changing and is considered Maya, which means it's not exactly what it seems to be. The absolute Atman-Brahman is realized by letting go of everything that is relative, limited, and changing.

This school accepts no separation. It believes there are no limited individual souls and no separate cosmic soul. All souls and their existence are considered to be the same oneness. Spiritual freedom in Advaita means fully understanding and realizing this oneness: that one's unchanging Atman is the same as the Atman in everyone else, and is also identical to Brahman.

Vishishtadvaita Vedanta (Qualified Non-Dualism)

Vishishtadvaita (pronounced "Vish-ish-tahd-VY-tah"), taught by Ramanuja (11–12th century), says that Jivatman (human souls) and Brahman (seen as Vishnu) are different, and this difference always remains. However, Ramanuja also said that there is a unity among all souls, and individual souls can realize their connection with Brahman. Vishishtadvaita is a non-dualistic school in a qualified way. It believes that all souls can achieve spiritual freedom. Regarding the relationship between Brahman and the world of matter (Prakriti), Vishishtadvaita says both are real and not illusions. Ramanuja believed that God, like humans, has both a soul and a body, and the material world is like God's glorious body. The way to Brahman (Vishnu), according to Ramanuja, is through devotion to God and constantly remembering the beauty and love of the personal God (bhakti).

Swaminarayan Darshana

The Swaminarayan Darshana, also called Akshar Purushottam Darshan by the BAPS organization, was started by Swaminarayan (1781-1830 CE). It is based on Ramanuja's Vishishtadvaita. This school teaches that Parabrahman (Purushottam, or Narayana) and Aksharbrahman are two distinct and eternal realities. Followers believe they can achieve moksha (freedom from rebirth) by becoming aksharrup (like Aksharbrahman) and worshipping Purushottam (the supreme living entity, God).

Tattvavada Vedanta (Dvaita) (Dualism)

Tattvavada, taught by Madhvacharya (13th century), is based on a realistic view of the world. The term Dvaita, meaning "dualism," was later used for Madhvacharya's philosophy. It sees Atman (soul) and Brahman (as Vishnu) as two completely different things. Brahman is the perfect creator of the universe, distinct from souls and matter. In Dvaita Vedanta, an individual soul must have attraction, love, and complete devotion to Vishnu to achieve salvation. Only His grace leads to freedom. Madhva also believed that some souls are eternally doomed, an idea not found in Advaita or Vishishtadvaita Vedanta.

Shuddhādvaita Vedanta (Pure Non-Dualism)

Shuddhadvaita (pure non-dualism), taught by Vallabhacharya (1479–1531 CE), says that the entire universe is real and is subtly Brahman in the form of Krishna. Vallabhacharya agreed with Advaita Vedanta's ideas about reality but stressed that prakriti (the physical world) is not separate from Brahman; it's just another way Brahman appears. Everything – soul and body, living and non-living – is the eternal Krishna. The way to Krishna in this school is through bhakti (devotion). Vallabha believed that giving up the world (sannyasa) was not effective and instead promoted the path of devotion over knowledge. The goal of bhakti is to turn away from ego and self-centeredness and to constantly turn towards the eternal Krishna in everything, which brings freedom from samsara (the cycle of rebirth).

History of Vedanta

The history of Vedanta can be divided into two main periods: before the Brahma Sutras were written, and after. Until the 11th century, Vedanta was not a very well-known school of thought.

Before the Brahma Sutras (before 5th century CE)

Not much is known about Vedanta schools before the Brahma Sutras were written (around 400–450 CE). Badarayana, who wrote the Brahma Sutras, was not the first to organize the Upanishads' teachings. He quoted six Vedanta teachers who came before him. The writings of these early teachers have not survived.

The Brahma Sutras (completed in 5th century CE)

Badarayana summarized and explained the teachings of the Upanishads in the Brahma Sutras, also called the Vedanta Sutra. This book likely brought together the ideas from the classical Upanishads and argued against other philosophies in ancient India. The Brahma Sutras formed the basis for the development of Vedanta philosophy.

Although attributed to Badarayana, the Brahma Sutras were probably written by several authors over hundreds of years. The book is made of four chapters, each with four sections. These sutras try to combine the different teachings of the Upanishads. However, the short, cryptic nature of the Brahma Sutras means they need explanations. These explanations led to the creation of many Vedanta schools, each interpreting the texts in its own way.

Between the Brahma Sutras and Adi Shankara (5th–8th centuries)

Little is known about the period between the Brahma Sutras (5th century CE) and Adi Shankara (8th century CE). Only two writings from this time have survived. Shankara himself mentioned 99 different teachers who came before him in his school.

An important scholar from this period was Bhartriprapancha. He believed that Brahman is one, but this unity has many different forms. Scholars see him as an early philosopher who taught the idea of Bhedabheda.

Gaudapada and Adi Shankara (Advaita Vedanta) (6th–9th centuries)

Advaita Vedanta was influenced by Buddhism and moved away from the bhedabheda philosophy. Instead, it stated that the Atman (soul) is the same as the Whole (Brahman).

Gaudapada

Gaudapada (around 6th century CE) was the teacher or a distant predecessor of Govindapada, who was Adi Shankara's teacher. Shankara is widely seen as the main figure of Advaita Vedanta. Gaudapada's book, the Kārikā, is the oldest complete text on Advaita Vedanta that still exists.

Gaudapada's Kārikā was based on the Mandukya, Brihadaranyaka, and Chhandogya Upanishads. In the Kārikā, Advaita (non-dualism) is explained using logic, separate from religious texts. Scholars disagree on whether Buddhism influenced Gaudapada's philosophy. The fact that Shankara wrote a separate commentary on the Kārikā shows how important it was in Vedanta.

Adi Shankara

Adi Shankara (788–820 CE) expanded on Gaudapada's work and older teachings. He wrote detailed explanations of the Prasthanatrayi and the Kārikā. Shankara described the Mandukya Upanishad and the Kārikā as containing "the essence of Vedanta." It was Shankara who combined Gaudapada's work with the ancient Brahma Sutras.

A well-known person at the time of Shankara was Maṇḍana Miśra. He thought that Mimamsa and Vedanta were part of a single system. Adi Shankara helped define the differences between the Vedanta and Mimamsa schools. For example, Advaita Vedanta rejects rituals and instead favors giving up worldly things.

Early Vaishnava Vedanta kept the bhedabheda tradition, seeing Brahman as Vishnu or Krishna.

Nimbārka and Dvaitādvaita

Nimbārka (7th century) taught Dvaitādvaita or Bhedābheda.

Bhāskara and Upadhika

Bhāskara (8th–9th century) also taught Bhedabheda. He believed that both identity and difference are equally real. He saw Brahman as a single, formless, pure being and intelligence. The same Brahman, when it appears as events, becomes the world of many different things. He believed that matter and its limits are real, not just an illusion. Bhaskara supported bhakti (devotion) as meditation focused on the ultimate Brahman. He disagreed with the idea of Maya (illusion) and said that spiritual freedom could not be achieved while still in a physical body.

The Bhakti movement in Hinduism began in the 7th century but grew rapidly after the 12th century. It was supported by texts like the Bhagavata Purana and many scholarly writings.

This period saw the rise of Vaishnavism communities (Sampradayas) influenced by scholars like Ramanujacharya, Madhvacharya, and Vallabhacharya. Bhakti poets and teachers also helped spread Vaishnavism. These founders of Vaishnavism challenged the dominant Advaita Vedanta ideas of Adi Shankara.

In North and Eastern India, Vaishnavism led to various movements in the late Middle Ages.

Ramanuja (Vishishtadvaita Vedanta) (11th–12th centuries)

Rāmānuja (1017–1137 CE) was the most important philosopher in the Vishishtadvaita tradition. He taught qualified non-dualism. Ramanuja disagreed with Advaita Vedanta and instead followed earlier teachers. He combined the Prasthanatrayi texts with the beliefs and philosophy of the Vaishnava poet-saints. Ramanuja wrote many important texts, including explanations of the Brahma Sutras and the Bhagavad Gita.

Ramanuja explained the importance of bhakti, or devotion to a personal God (Vishnu in his case), as a way to spiritual freedom. His ideas state that there are many different souls (Atman) and that they are distinct from Brahman (the ultimate reality). However, he also said that all souls are connected and can realize their unity with Brahman. Vishishtadvaita provides the philosophical basis for Sri Vaishnavism.

Ramanuja was very important in bringing Bhakti (devotional worship) into the core ideas of Vedanta.

Madhva (Tattvavada or Dvaita Vedanta) (13th–14th centuries)

Tattvavada or Dvaita Vedanta was taught by Madhvacharya (1238–1317 CE). He offered a different interpretation from Shankara, creating his Dvaita, or dualistic, system. Unlike Shankara's non-dualism and Ramanuja's qualified non-dualism, Madhva supported complete dualism. Madhva wrote explanations of the main Upanishads, the Bhagavad Gita, and the Brahma Sutra.

Madhva was very critical of other Hindu philosophies, Jainism, and Buddhism, especially Advaita Vedanta and Adi Shankara.

Dvaita Vedanta is focused on God and sees Brahman as Narayana, or Vishnu, similar to Ramanuja's Vishishtadvaita Vedanta. But it is more clearly pluralistic, meaning it believes in many distinct things. Madhva strongly emphasized the differences between the soul and Brahman. He taught that there were differences between: (1) material things; (2) material things and souls; (3) material things and God; (4) different souls; and (5) souls and God. He also believed there were different levels of knowledge and even different levels of happiness for liberated souls, which is a unique idea in Indian philosophy.

Chaitanya Mahaprabhu (Achintya Bheda Abheda) (16th century)

Achintya Bheda Abheda (Vaishnava) was founded by Chaitanya Mahaprabhu (1486–1534 CE) and spread by Gaudiya Vaishnava. Chaitanya Mahaprabhu started the practice of chanting the holy names of Krishna in groups in the early 16th century after becoming a sannyasi (renunciant).

Modern Times (19th century – Present)

Swaminarayan and Akshar-Purushottam Darshan (19th century)

The Swaminarayan Darshana, which is based on Ramanuja's Vishishtadvaita, was founded in 1801 by Swaminarayan (1781-1830 CE). Today, it is most notably spread by the BAPS organization. The Akshar-Purushottam teachings were recognized as a distinct school of Vedanta in 2017 and 2018. Some scholars describe it as a seventh school of Vedanta.

Neo-Vedanta (19th century)

Neo-Vedanta, also called "Hindu modernism," is a term for new interpretations of Hinduism that appeared in the 19th century. This happened partly as a reaction to British colonial rule. Some scholars believe these ideas helped Hindu nationalists create a national identity to fight against colonial rule. Western scholars tried to define "Hinduism" based on a single interpretation of Vedanta, even though Hinduism and Vedanta have always had many different traditions.

Neo-Vedantins argued that the six traditional Hindu philosophy schools were all different ways of looking at the same truth, and that they were all valid and worked together. These interpretations often included Western ideas into traditional systems, especially Advaita Vedanta. Neo-Vedantists included Buddhist philosophies as part of the Vedanta tradition and argued that all world religions share the same "non-dualistic position," ignoring the differences within and outside of Hinduism.

A key person in making this Universalist interpretation of Advaita Vedanta popular was Vivekananda. He played a major role in the revival of Hinduism and helped spread Advaita Vedanta to the West through the Vedanta Society.

Criticism of Neo-Vedanta label

Some scholars criticize the term "Neo-Hinduism" as an idea created by Western scholars. They argue that Indian tradition was always self-aware and critical, not just a reaction to Western culture. They believe that figures like Gandhi, Vivekananda, and Tagore were not simply "transplants from Western culture" but were part of India's own ongoing discussions and challenges.

Influence of Vedanta

According to scholars, the Vedanta school has had a very important and central influence on Hinduism: It is found not only in philosophical writings but also in Hindu literature like epics, poetry, and plays. Hindu religious groups and the common faith of Indian people looked to Vedanta philosophy for the ideas behind their beliefs. Vedanta's influence is strong in sacred Hindu texts like the Puranas and Tantras.

One scholar, Frithjof Schuon, says that Vedanta is a valuable key to understanding the deepest meaning of all religious ideas and realizing that the Sanatana Dharma (eternal truth) secretly connects all traditional spiritual paths.

Gavin Flood states that Vedanta has been the most influential school of theology in India. It has greatly affected all religious traditions and became the main philosophy of the Hindu revival in the 19th century. It is now seen as the ultimate philosophical model of Hinduism.

Hindu Traditions

Vedanta, by taking ideas from other traditional Hindu schools, became the most important school of Hinduism. Vedanta traditions led to the development of many traditions within Hinduism. Sri Vaishnavism in South India is based on Ramanuja's Vishishtadvaita Vedanta. Ramananda led the Vaishnav Bhakti Movement in North, East, Central, and West India, which draws its ideas from Vishishtadvaita. Many devotional Vaishnavism traditions are based on different sub-schools of Bhedabheda Vedanta. Advaita Vedanta influenced Krishna Vaishnavism in Assam. The Madhva school of Vaishnavism in coastal Karnataka is based on Dvaita Vedanta.

Āgamas, the classical texts of Shaivism (worship of Shiva), also show connections to Vedanta ideas. Of the 92 Āgamas, some are dualistic, some are bhedabheda, and many are advaita. Tirumular, a Tamil Shaiva Siddhanta scholar, said that becoming Shiva is the goal of Vedanta and Siddhanta.

Shaktism, traditions where a goddess is seen as the same as Brahman, also grew from a mix of Advaita Vedanta's ideas of oneness and the dualism of the Samkhya–Yoga school.

Influence on Western Thinkers

Ideas have been exchanged between the Western world and Asia since the late 18th century. This also affected Western religious thought. The first translation of Upanishads, published in 1801 and 1802, greatly influenced Arthur Schopenhauer, who called them the comfort of his life. He saw clear similarities between his own philosophy and Vedanta. Early translations also appeared in other European languages. Influenced by Shankara's ideas of Brahman (God) and māyā (illusion), Lucian Blaga often used concepts like "the Great Anonymous" and "the transcendental censorship" in his philosophy.

Similarities with Spinoza's Philosophy

German scholar Theodore Goldstücker was among the first to notice similarities between Vedanta and the ideas of the Dutch Jewish philosopher Baruch Spinoza. He wrote that Spinoza's thought was so similar to Vedanta that one might think he borrowed ideas from Hindus, if not for the fact that he knew nothing about their teachings.

Max Müller also noted the striking similarities between Vedanta and Spinoza's system, saying that the Brahman in the Upanishads and defined by Shankara is clearly the same as Spinoza's "Substance."

Helena Blavatsky, a founder of the Theosophical Society, also compared Spinoza's religious thought to Vedanta.

See also

In Spanish: Vedānta para niños

In Spanish: Vedānta para niños

- Badarayana

- Monistic idealism

- List of teachers of Vedanta

- Self-consciousness (Vedanta)

- Śāstra pramāṇam in Hinduism

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |