Johann Gottlieb Fichte facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Johann Gottlieb Fichte

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 19 May 1762 Rammenau, Saxony, Holy Roman Empire

|

| Died | 29 January 1814 (aged 51) |

| Nationality | German |

| Education | Schulpforta University of Jena (1780; no degree) Leipzig University (1781–1784; no degree) |

| Era | 18th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Continental philosophy German idealism Post-Kantian transcendental idealism Empirical realism Foundationalism Coherence theory of truth Jena Romanticism Romantic nationalism |

| Institutions | University of Jena University of Erlangen University of Berlin |

| Academic advisors | Immanuel Kant |

| Notable students | Novalis Friedrich Schlegel Friedrich Hölderlin August Ludwig Hülsen Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling |

|

Main interests

|

Self-consciousness and self-awareness, moral philosophy, political philosophy |

|

Notable ideas

|

List

Das absolute Bewusstsein (the absolute consciousness)

Thesis–antithesis–synthesis Das Nicht-Ich (the not-I) Das Streben (striving) Wissenschaftslehre (Doctrine of Science) as Real-Idealismus/Ideal-Realismus ("real-idealism/ideal-realism") Philosophy as pragmatic history of the human spirit Gegenseitig anerkennen (mutual recognition) Principle of reciprocal determination Anstoss (impulse) Tathandlung (fact and/or act) Aufforderung (calling, summons) Philosophical reflection as intellectual intuition The primacy of the practical (Handeln) Urtrieb (original drive) "Fichte's original insight" The power of productive imagination as an original power of the mind |

|

Influences

|

|

|

Influenced

|

|

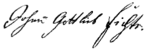

| Signature | |

|

|

Johann Gottlieb Fichte (born May 19, 1762 – died January 29, 1814) was an important German philosopher. He helped start a big philosophical movement called German idealism. This movement grew from the ideas of another famous philosopher, Immanuel Kant.

Recently, experts have started to see Fichte as a very important thinker on his own. He had new ideas about how we become self-conscious or aware of ourselves. Fichte also came up with the idea of thesis–antithesis–synthesis, which is a way of thinking about how ideas develop. People often mistakenly think this idea came from Hegel. Like Descartes and Kant, Fichte was interested in how we experience the world and how our minds work. He also wrote about political philosophy and is sometimes called one of the founders of German nationalism.

Contents

Biography

Early Life and Education

Johann Gottlieb Fichte was born in Rammenau, a small town in Germany. His family were ribbon weavers and had lived in the area for many generations. They were known for being honest and religious.

Fichte was very smart from a young age. A local landowner, Freiherr von Miltitz, heard about Fichte's amazing memory. The story goes that Fichte could repeat a sermon almost word for word! Because of this, the baron decided to help Fichte get a better education. He paid for Fichte's schooling.

In October 1774, Fichte went to a famous school called Pforta. This school taught him a lot about classics, like ancient Greek and Roman texts. The school was very strict, almost like a monastery. This might have made Fichte more focused on his own thoughts and ideas, which showed up in his later writings.

University and Tutoring

In 1780, Fichte started studying theology at the University of Jena. A year later, he moved to Leipzig University. He had to support himself during this time, and it was a period of great poverty for him. Without the baron's financial help, Fichte had to stop his studies before getting a degree.

From 1784 to 1788, Fichte worked as a private tutor for different families. In 1788, he moved to Zurich in Switzerland. He lived there for two happy years. In Zurich, he met Johanna Rahn, who would become his wife. He also became a member of a Freemasonry group.

Meeting Kant

In the summer of 1790, Fichte started studying the works of Immanuel Kant. He became very interested in Kant's ideas. However, Johanna's family faced money problems, and their wedding had to be delayed.

In 1791, Fichte traveled to Königsberg to meet Kant. After their first meeting didn't go well, Fichte quickly wrote an essay to impress Kant. This essay was called Attempt at a Critique of All Revelation.

The first edition of this book was published without Fichte's name on it. People thought it was a new work by Kant himself! When Kant cleared up the confusion and praised Fichte's work, Fichte became famous very quickly.

Teaching at Jena

In October 1793, Fichte married Johanna in Zurich. He was inspired by the French Revolution and wrote some anonymous pamphlets supporting freedom of thought. In December of that year, he was invited to become a professor of philosophy at the University of Jena. He started teaching there in May 1794.

Fichte was a very energetic and powerful speaker. His lectures were very popular and were later published as The Vocation of the Scholar. He wrote many new works during this time.

Atheism Controversy

Fichte faced some challenges in his academic career. In 1799, he was fired from the University of Jena because of accusations of atheism. This happened after he published an essay where he said that God should be understood as the "living and active moral order" of the world. He wrote, "We require no other God, nor can we grasp any other."

Fichte's strong response to these accusations made the situation worse. Another philosopher, F. H. Jacobi, even said that Fichte's philosophy was like nihilism, which is the belief that life has no meaning.

Life in Berlin

Since most German states didn't want Fichte to teach, he moved to Berlin. There, he met other important thinkers and writers. In 1800, he joined another Freemasonry lodge.

In November 1800, Fichte published a book called The Closed Commercial State. In this book, he shared his ideas about property, economics, and how a country should be run.

In 1805, he became a professor at the University of Erlangen. After Napoleon's army defeated Prussia in 1806, Fichte returned to Berlin. He continued to write, including a book about the famous political thinker Niccolò Machiavelli.

Between 1807 and 1808, Fichte gave his famous Addresses to the German Nation. In these speeches, he tried to explain what made the German nation special. He wanted to inspire Germans to stand up against Napoleon's rule.

In 1810, the new University of Berlin was founded. Fichte became its first professor of philosophy and was even elected its rector (head of the university) in 1811. However, his strong desire for reform led to disagreements, and he resigned in 1812.

When the war against Napoleon began, many soldiers were injured. Fichte's wife helped nurse the sick and caught a serious fever. As she was recovering, Fichte himself became sick with typhus and died in 1814 at the age of 51. His son, Immanuel Hermann Fichte, also became a philosopher.

Fichte's Philosophical Ideas

Fichte's writings were known for being difficult to understand. Some critics said his style was too unclear. However, Fichte believed that his ideas were clear to anyone who was willing to think deeply without old ideas getting in the way.

Fichte disagreed with Kant's idea of "things in themselves" (called noumena), which were supposed to be a reality beyond what we can sense. Fichte thought this idea could lead to skepticism, where people doubt everything. Instead, Fichte suggested that our consciousness doesn't need anything outside itself to exist. He believed that the world we experience comes from the activity of our own minds and our moral awareness. He became famous for saying that consciousness is not based on anything outside of itself.

How We Become Self-Aware

In his book Foundations of Natural Right (1797), Fichte argued that being self-conscious is something that happens because of other people. He believed that for you to be aware of yourself as a free person, other thinking people must exist. These others "call" or "summon" you out of being unaware and into knowing yourself as an individual.

Fichte thought that to see yourself as an individual, you have to recognize that others are also free. This means you limit your own freedom out of respect for theirs. This idea of "mutual recognition" (gegenseitig anerkennen) between people is key to how Fichte saw selfhood.

Fichte also talked about an "impulse" or "resistance" (Anstoss) that limits our freedom. This Anstoss is not something outside of us, but rather our own mind encountering its limits. It's what starts the whole process of us becoming aware of ourselves and the world around us.

Nationalism and Identity

Between 1807 and 1808, Fichte gave a series of lectures called the Addresses to the German Nation. In these speeches, he talked about the German language and culture. He hoped that a special kind of national education would help Germany recover from its defeat by Napoleon.

Fichte had supported the French Revolution at first. But as Napoleon's armies took over German lands, Fichte became disappointed. He believed Germany had a special role to carry the good ideas of the French Revolution into the future. He saw Germany's goal as building an "empire of spirit and reason" to overcome physical force. Like other German thinkers, Fichte's idea of nationalism was based on culture, art, literature, and morals.

It's important to note that Fichte's ideas on nationalism were later used by the Nazi Party in Germany, who saw him as a supporter of their own nationalist beliefs. This has affected how people view Fichte's legacy. Also, in an early letter from 1793, Fichte expressed some negative views about Jewish people, arguing against giving them full civil rights. However, he also added a note strongly asking for Jews to be allowed to practice their religion freely. Later in his life, Fichte even resigned from his position at the University of Berlin because his colleagues refused to stop the harassment of Jewish students.

Fichte himself, in a later work, clearly spoke against harming people for their beliefs: "If you say that it is your conscience's command to exterminate peoples for their sins, [...] we can confidently tell you that you are wrong; for such things can never be commanded against the free and moral force."

Economic Ideas

Fichte's 1800 book The Closed Commercial State also had a big impact on economic thinking in Germany. In it, Fichte argued that industries should be strictly controlled, almost like guilds. He believed that a country should not let just anyone produce goods without proper training and government approval.

Fichte was against free trade and uncontrolled growth of factories. He thought that too much competition led to "an endless war of all against all." He believed this war became worse as the world's population grew and as more goods were produced.

To solve these problems, Fichte suggested that the "world state" (the global market) should be divided into separate, self-sufficient countries. Each "closed trading state" would control its own economy. It would produce everything its citizens needed and organize production perfectly. Fichte argued that government control was needed to limit industries and make sure they served the people.

Views on Women

Fichte believed that women should not have full rights as citizens, including voting or owning property. He thought their main role was to be completely under the authority of their fathers and husbands.

Later Years in Berlin

In his last decade, Fichte gave many public and private lectures in Berlin. These lectures became some of his most famous works and are still studied today.

Some of his important works from this period include:

- The Characteristics of the Present Age (1806), where he described his ideas about different historical periods.

- His spiritual work The Way Towards the Blessed Life (1806), which shared his deepest thoughts on religion.

- The Addresses to the German Nation (1807-1808), given during the French occupation of Berlin.

When the new University of Berlin was founded in 1810, Fichte became its first professor of philosophy and its rector. This was partly because of his ideas on education in his Addresses.

Fichte continued to teach new versions of his main philosophical system, the Wissenschaftslehre (Doctrine of Science). He only published a short version of it in 1810. Many of his later lectures were only published decades after his death. These included new versions of his Doctrine of Science (1810–1813), The Science of Rights (1812), and The Science of Ethics (1812).

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Johann Gottlieb Fichte para niños

In Spanish: Johann Gottlieb Fichte para niños

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |