Giovanni Gentile facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Giovanni Gentile

|

|

|---|---|

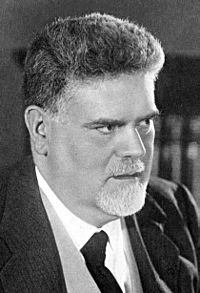

Gentile, 1930s

|

|

| President of the Royal Academy of Italy | |

| In office 25 July 1943 – 15 April 1944 |

|

| Monarch | Victor Emmanuel III |

| Preceded by | Luigi Federzoni |

| Succeeded by | Giotto Dainelli Dolfi |

| Minister of Public Education | |

| In office 31 October 1922 – 1 July 1924 |

|

| Prime Minister | Benito Mussolini |

| Preceded by | Antonino Anile |

| Succeeded by | Alessandro Casati |

| Member of the Italian Senate | |

| In office 11 June 1921 – 5 August 1943 |

|

| Monarch | Victor Emmanuel III |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 30 May 1875 Castelvetrano, Kingdom of Italy |

| Died | 15 April 1944 (aged 68) Florence, RSI |

| Resting place | Santa Croce, Florence, Italy |

| Political party | National Fascist Party (1923–1943) |

| Spouse |

Erminia Nudi

(m. 1901) |

| Children | 6, including Federico Gentile |

| Alma mater | Scuola Normale Superiore University of Florence |

| Profession | Teacher, philosopher, politician |

| Signature |  |

|

Philosophy career |

|

|

Notable work

|

|

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Neo-Hegelianism |

|

Main interests

|

Metaphysics, dialectics, pedagogy |

|

Notable ideas

|

Actual idealism, fascism, immanentism (method of immanence) |

|

Influenced

|

|

Giovanni Gentile (born May 30, 1875 – died April 15, 1944) was an Italian thinker, teacher, and politician. He was known as the "philosopher of Fascism" by himself and by Benito Mussolini. He helped create the ideas behind Italian Fascism. He also helped write part of The Doctrine of Fascism (1932) with Mussolini. Gentile was important in bringing back a type of philosophy called Hegelian idealism in Italy. He also developed his own ideas, which he called "actual idealism". This way of thinking focused on how our minds create reality.

Contents

Biography

Early life and education

Giovanni Gentile was born in Castelvetrano, Italy. He was inspired by Italian thinkers from the Risorgimento era. This was a time when Italy became a unified country. He also learned a lot from German philosophers like Hegel and Fichte.

Gentile was a very smart student. He won a tough competition to study at the famous Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa. In 1898, he finished his studies in Letters and Philosophy. His main paper was about two other Italian philosophers, Rosmini and Gioberti.

During his career, Gentile taught at several universities. He was a professor at the University of Palermo and the University of Pisa. Later, he taught at the University of Rome. He also led the Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa for many years.

Involvement with Fascism

In 1922, Giovanni Gentile became the Minister of Public Education. He worked for the government led by Benito Mussolini. In this role, he created the "Riforma Gentile". This was a major change to Italy's school system. It had a lasting effect on how students were educated.

His philosophical ideas, like "actual idealism", said that thinking and life should not be separate. He believed that philosophy should guide how people live. He thought that our minds actively create the world we experience.

In 1925, Gentile helped create new laws for the Fascist government. He also became president of the Grand Council of Public Education. He even joined the powerful Fascist Grand Council.

Gentile's ideas were very important to Fascist philosophy. He believed that everything was connected through thought. He thought that the state was the most important authority. He felt that individuals only had meaning within the state. This idea helped support the totalitarian nature of Fascism.

Mussolini and Gentile both called him "the philosopher of Fascism". Gentile also helped write the first part of the essay The Doctrine of Fascism (1932). This essay described key features of Italian Fascism. These included strong state control and the idea of "Philosopher Kings". It also talked about getting rid of the parliament. Gentile also wrote the Manifesto of the Fascist Intellectuals. Many famous writers signed this document.

Gentile stayed loyal to Mussolini even after the Fascist government fell in 1943. He supported Mussolini's new government, the "Republic of Salò". This was a state controlled by Nazi Germany. Gentile became the last president of the Royal Academy of Italy.

Assassination

On March 30, 1944, Gentile received threats. People blamed him for the execution of some people by the Republic of Salò troops. They also accused him of supporting fascism.

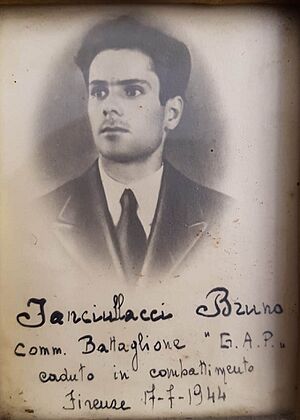

Two weeks later, on April 15, 1944, two members of a communist group approached Gentile. Their names were Bruno Fanciullacci and Antonio Ignesti. They were hiding pistols behind a book. When Gentile opened his car window to talk, he was shot several times. He died from his injuries.

Giovanni Gentile was buried in the church of Santa Croce in Florence.

Philosophy

Benedetto Croce, another famous philosopher, said that Gentile was a very strict follower of a philosophy called neo-Hegelianism. Croce also noted that Gentile became the official philosopher of Fascism in Italy. Gentile's ideas about how we understand reality helped him argue against individualism. He supported the idea of collectivism. He believed the state was the highest authority. He thought that individuals had no meaning outside of the state. This helped justify the totalitarian side of fascism.

Gentile's main idea was called "actual idealism". This philosophy said that the "pure act" of thinking is most important. He believed that this act creates the world we see. He thought that our minds are constantly creating reality. This idea also connected to his work as a teacher. For Gentile, learning was a way to understand this deeper reality. He believed that all our sensations and ideas are created within our minds. Some people thought his philosophy meant that only the mind is real.

His ideas also touched on religion. For example, he thought that even if humans created the idea of God, it doesn't make God any less real. This is because God exists as a concept within our minds. Gentile called his idea "absolute Immanentism". This meant that the divine is found in our present understanding of reality. He saw it as a constantly changing and growing process within our own thinking.

See also

In Spanish: Giovanni Gentile para niños

In Spanish: Giovanni Gentile para niños