Italian fascism facts for kids

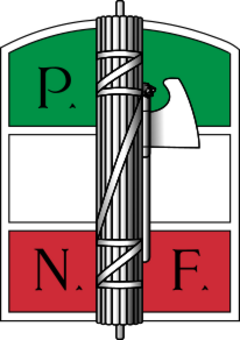

Italian fascism (called fascismo italiano in Italian) was the first type of fascist ideology. It was created in Italy by Giovanni Gentile and Benito Mussolini. This way of thinking is linked to political parties led by Mussolini, like the National Fascist Party (PNF). This party ruled the Kingdom of Italy from 1922 to 1943. Later, the Republican Fascist Party (PFR) ruled the Italian Social Republic from 1943 to 1945. After World War II, Italian fascism also influenced groups like the Italian Social Movement (MSI) and other neo-fascist groups.

Italian fascism mixed ideas from ultranationalism and Italian nationalism, national syndicalism, and revolutionary nationalism. It also included the strong military ideas of Italian irredentism, which wanted to get back "lost Italian lands overseas." Fascists believed this would bring back Italian pride. They also thought modern Italy was like the Roman Empire. They wanted to create an Imperial Fascist Italy to gain spazio vitale (living space). This led to the Second Italo-Senussi War and efforts to control the Mediterranean Sea.

Italian fascism supported a corporatist economic system. In this system, groups of employers and employees worked together with the government. They set national economic policies. This system aimed to solve class conflict by encouraging cooperation between different social classes.

Italian fascism was against liberalism, especially classical liberalism, which they called "the failure of individualism." They also opposed socialism because it often went against nationalism. However, they were also against the old-fashioned conservatism of Joseph de Maistre. Fascists believed that for Italian nationalism to succeed, people needed to respect tradition and feel a strong connection to their shared past. They also wanted a modern Italy.

At first, many Italian fascists did not like Nazism. However, many fascists, including Mussolini, held racist ideas, especially against Slavic people. These ideas became official laws during fascist rule. As Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany became closer in the late 1930s, Italian laws became openly antisemitic. This was due to pressure from Nazi Germany, even though these laws were not always strictly enforced in Italy. The Italian racial laws were passed. When fascists were in power, they also treated some language minorities in Italy badly. Greeks in Dodecanese and Northern Epirus, which were under Italian control, also faced persecution.

Contents

Main Ideas of Italian Fascism

Italian Nationalism

Italian fascism was built on Italian nationalism. It especially wanted to finish the Risorgimento project, which was about uniting Italy. Fascists wanted to bring Italia Irredenta (unredeemed Italy) into the Italian state. The National Fascist Party (PNF), started in 1921, said it was a "revolutionary army serving the nation." It followed three rules: order, discipline, and hierarchy.

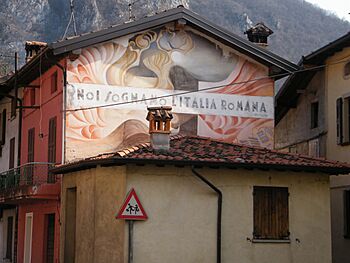

Fascists saw modern Italy as the heir to the Roman Empire and Italy during the Renaissance. They promoted the cultural idea of Romanitas (Roman-ness). Italian fascism wanted to build a strong Italian Empire as a Third Rome. They saw ancient Rome as the First Rome and Renaissance Italy as the Second Rome. Italian fascism directly promoted imperialism. For example, in Doctrine of Fascism (1932), written for Mussolini by Giovanni Gentile, it says:

The Fascist state wants power and empire. The Roman tradition is a strong force here. An empire is not just about land, military, or trade. It is also about spirit and morals. One can think of an empire, a nation, that guides other nations without needing to conquer any land.

Claiming More Land

Fascism stressed the need to bring back the ideas of Giuseppe Mazzini from the Risorgimento. Fascists believed that the unification of Italy was not complete. They wanted to add "unredeemed" territories to Italy.

To the east, fascists claimed Dalmatia was Italian. They said Italians from there had been forced to leave. Mussolini said Dalmatia had strong Italian roots from the Roman Empire and the Republic of Venice. Fascists were angry when, after World War I, Dalmatia was not given to Italy as promised in the 1915 Treaty of London. The fascist government wanted to take over Slovenia and force Italianization on its people. They also made German and Slavic languages illegal in schools and changed names to Italian. This led to harsh treatment against South Slavs who resisted. The fascists also wanted to take Albania. They claimed Albanians were linked to Italians and that Roman and Venetian rule justified Italy owning it. After Italy took Albania in 1939, fascists wanted to make Albanians more Italian and send Italian settlers there. They also claimed the Ionian Islands because they had belonged to Venice.

To the west, fascists claimed Corsica, Nice, and Savoy from France. These lands were given to France in 1860-1861 during Italy's unification. Fascists published writings to show the "Italianness" of Corsica and Nice. They quoted famous Italians like Petrarch and Giuseppe Garibaldi who said these lands should be part of Italy. Mussolini first tried to get Corsica by supporting its independence from France, then annexing it to Italy.

To the north, in the 1930s, the fascist government wanted parts of Switzerland, like Ticino (mostly Italian-speaking) and Graubünden (Romansch-speaking). Mussolini claimed Romansch was an Italian dialect. He said Italy's border should move to the Gotthard Pass.

To the south, the fascists claimed Malta, which was controlled by the British. Mussolini said the Maltese language was an Italian dialect. Italian was widely used in Malta until 1937. Fascists also claimed parts of North Africa as Italy's "Fourth Shore." They used ancient Roman rule there to justify taking these lands. In 1939, Italy annexed parts of Libya, making them part of Italy. Libyans could apply for "Special Italian Citizenship" if they spoke Italian. Tunisia, a French protectorate, had many Italians. Italy saw its loss to France as an insult. During World War II, Italy planned to take Tunisia and parts of Algeria from France.

The fascist government also wanted to expand Italy's colonies in Africa. In the 1920s, they saw Portugal as a weak colonial power and wanted to take its colonies.

Racism in Fascism

Before Benito Mussolini allied with Adolf Hitler, he said there was no antisemitism in the National Fascist Party (PNF).

In 1929, Mussolini recognized the contributions of Italian Jews to society. He believed Jewish culture was Mediterranean, like his own early views. He also said Jews were native to Italy. At first, Fascist Italy did not have widespread racist policies like Nazi Germany. Mussolini had different views on race over time. In 1932, he said, "Race? It is a feeling, not a reality." But by 1938, he supported racist policies. He endorsed the "Manifesto of Race," which said Italians should be "openly racist." Mussolini later said this was "entirely for political reasons," to please Nazi Germany. The "Manifesto of Race," published on July 14, 1938, led to the Racial Laws. Some top fascists, like Dino Grandi and Italo Balbo, were against these laws. Balbo thought antisemitism had nothing to do with fascism. After 1938, discrimination grew stronger in fascist ideas. However, Mussolini and the military did not always strictly follow these laws. In 1943, Mussolini regretted endorsing the manifesto. After the Second Italo-Ethiopian War, the Italian fascist government created strict racial segregation between white and black people in Ethiopia.

Total Control of the State

In 1925, the PNF declared that Italy's fascist state would be totalitarian. This word was first used by opponents to criticize the fascists for wanting a complete dictatorship. But fascists accepted the term and presented it positively. Mussolini said totalitarianism aimed to create a strong national state. This state would finish the Risorgimento, build a powerful modern Italy, and create new, politically active fascist citizens.

The Doctrine of Fascism (1932) explained fascist totalitarianism:

Fascism believes in the only true freedom: the freedom of the state and of the individual within the state. So, for a fascist, everything is in the state. Nothing human or spiritual exists, or has value, outside the state. In this way, fascism is totalitarian. The fascist state brings together and strengthens all values, guiding the entire life of the people.

An American journalist, H. R. Knickerbocker, wrote in 1941 that Mussolini's fascist state was the "least terroristic" of the three totalitarian states (compared to Soviet or Nazi).

However, historians after World War II noted that Italian fascism used extreme violence in its colonies. One-tenth of the population in the Italian colony of Libya died during the fascist era. This was due to things like gassings, concentration camps, starvation, and disease. In Ethiopia, during and after the Second Italo-Ethiopian War, a quarter of a million Ethiopians died by 1938.

Corporatist Economy

Italian fascism promoted a corporatist economic system. In this system, groups of employers and employees worked together in associations. They represented the nation's economic producers and worked with the state to set national economic policy. Mussolini called this economy a "Third Alternative" to capitalism and Marxism, which he saw as "outdated ideas." For example, he said in 1935 that traditional capitalism no longer existed in Italy. Plans in 1939 aimed to divide the country into 22 corporations, with representatives from each industry going to Parliament.

Almost all business activities needed state permission. This included expanding factories, merging businesses, or firing employees. The government set all wages and created a minimum wage. Rules for workers became stricter. While businesses could still make profits, Italian fascism made strikes by workers and lockouts by employers illegal. They saw these as harmful to the nation.

Age and Gender Roles

The political song of Italian fascists was called Giovinezza (Youth). Fascism saw youth as a very important time for people's moral growth, which would affect society.

Mussolini believed women's main role was to have children, while men were warriors. He once said, "war is to man what maternity is to the woman." To increase birth rates, the fascist government tried to reduce the need for families to have two incomes. A key policy was to encourage large families, giving money to parents for each child. In 1934, Mussolini said women working was a "major problem of unemployment" and "incompatible with childbearing." He said the solution for male unemployment was for "women to leave the work force." Although the first Fascist Manifesto mentioned voting rights for everyone, this opposition to feminism meant that when women got the right to vote in 1925, it was only for local elections and for a small number of women. This reform quickly became useless when local elections were stopped in 1926.

Importance of Tradition

Italian fascism believed that for Italian nationalism to succeed, Italians needed a clear sense of their shared past. They also wanted a modern Italy. In a famous speech in 1926, Mussolini called for fascist art to be "traditionalist and at the same time modern, looking to the past and at the same time to the future."

Fascists used traditional symbols from Roman civilization, especially the fasces. This symbol stood for unity, authority, and power. Other ancient Roman symbols they used included the she-wolf. Both the fasces and the she-wolf showed the shared Roman heritage of all Italian regions. In 1926, the fascist government made the fasces a state symbol. They tried to put it on the Italian national flag, but Italian monarchists strongly opposed this. After that, the fascist government used the national flag and a black fascist flag in public ceremonies. Years later, after Mussolini was removed from power and then rescued by German forces, the Italian Social Republic (founded by Mussolini) did put the fasces on its war flag.

The question of whether Italy should be a monarchy or a republic changed several times in Italian fascism. At first, Italian fascism was republican and against the Savoy monarchy. But Mussolini smartly gave up republicanism in 1922. He realized that accepting the monarchy was necessary to get support from the powerful groups that also supported the monarchy. King Victor Emmanuel III was popular after Italy's gains in World War I, and the army was loyal to him. So, the fascists decided it was foolish to try to overthrow the monarchy then. Importantly, accepting the monarchy gave fascism a sense of historical link and legitimacy. Fascists publicly linked King Victor Emmanuel II, the first King of a united Italy, and other historical figures like Julius Caesar, Giuseppe Mazzini, Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour, and Giuseppe Garibaldi, to a tradition of strong leadership in Italy that fascists said they followed. However, this agreement with the monarchy did not lead to a friendly relationship between the King and Mussolini. Even though Mussolini formally accepted the monarchy, he worked to reduce the King's power to that of a figurehead. In the 1930s, Mussolini was annoyed that the monarchy still existed. He envied Adolf Hitler in Germany, who was both head of state and head of government of a republic. Mussolini privately criticized the monarchy and planned to get rid of it and create a republic with himself as head of state if Italy won the big war he expected in Europe.

After the King removed Mussolini from office and arrested him in 1943, and the Kingdom of Italy switched sides to the Allies, Italian fascism went back to being republican and criticizing the monarchy. On September 18, 1943, Mussolini gave his first public speech after being rescued by German forces. He praised Hitler's loyalty but condemned King Victor Emmanuel III for betraying Italian fascism. About the monarchy removing him and ending the fascist rule, Mussolini said: "It is not the regime that has betrayed the monarchy, it is the monarchy that has betrayed the regime." He added that "When a monarchy fails in its duties, it loses every reason for being. ... The state we want to create will be national and social in the highest sense; that is, it will be fascist, returning to our beginnings." At this point, fascists did not criticize the entire history of the House of Savoy. They praised Victor Emmanuel II for rejecting "dishonorable agreements" but condemned Victor Emmanuel III for betraying Victor Emmanuel II by making a dishonorable agreement with the Allies.

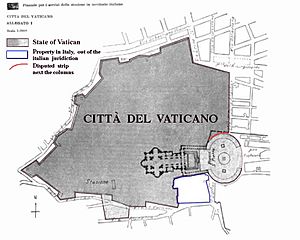

The relationship between Italian fascism and the Catholic Church was complicated. At first, fascists were very anti-church and against Catholicism. But from the mid to late 1920s, anti-church feelings lessened in the movement. Mussolini, in power, tried to make peace with the Church because it had a lot of influence in Italian society, as most Italians were Catholic. In 1929, the Italian government signed the Lateran Treaty with the Holy See. This agreement between Italy and the Catholic Church created a small country called Vatican City as a sovereign state for the papacy. This ended years of tension between the Church and the Italian government after Italy took over the Papal States in 1870. Italian fascism tried to justify its antisemitic laws in 1938 by claiming Italy was following a Christian religious rule from the Catholic Church. This rule was started by Pope Innocent III in the Fourth Lateran Council of 1215, which set strict rules for Jews living in Christian lands. Jews were not allowed to hold public office that would give them power over Christians, and they had to wear special clothing.

Fascist Ideas and Beliefs

The Doctrine of Fascism (La dottrina del fascismo), published in 1932, is the official explanation of Italian fascism. It was written by the philosopher Giovanni Gentile but published under Benito Mussolini's name in 1933. Gentile was influenced by thinkers like Hegel, Plato, Benedetto Croce, and Giambattista Vico. His philosophy, called actual idealism, was the basis for fascism. The Doctrine sees the world as a place of action for humans. It rejects "everlasting peace" as a fantasy and believes humans are always at war. Those who face challenges become noble. It generally believed that conquerors, like the Roman Julius Caesar, the Greek Alexander the Great, and the French Napoleon, were important historical figures.

In 1925, Mussolini took the title Duce (Leader), which came from the Latin word dux (leader), a Roman military title. Even though fascist Italy (1922–1943) is seen as an authoritarian dictatorship, it kept the appearance of a "liberal democratic" government. The Grand Council of Fascism continued to work, and King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy could, at risk to his own power, dismiss Mussolini as Italian Prime Minister, which he eventually did.

Gentile described fascism as an idea based on faith rather than reason. Fascist ideas emphasized the importance of political myths. These myths were seen as true not as facts, but as a "higher reality." Fascist art, architecture, and symbols helped turn Fascism into a kind of civil religion or political religion. La dottrina del fascismo says fascism is a "religious way of life" and forms a "spiritual community," unlike materialistic ideas. The slogan Credere Obbedire Combattere ("Believe, Obey, Fight") shows how important political faith was in fascism.

According to historian Zeev Sternhell, "most syndicalist leaders were among the founders of the fascist movement." These leaders later got important jobs in Mussolini's government. Mussolini greatly admired the ideas of Georges Sorel, saying he helped create the main principles of Italian fascism. J. L. Talmon argued that fascism presented itself "not only as an alternative, but also as the heir to socialism."

La dottrina del fascismo suggested that Italy would have better living standards under a one-party fascist system than under the multi-party liberal democratic government of 1920. As the leader of the National Fascist Party (PNF), Mussolini said that democracy is "beautiful in theory; in practice, it is a fallacy." In 1923, to give Mussolini control of the pluralist parliament, a law called the Acerbo Law was passed. This law changed the voting system. The party with the most votes (if they had at least 25%) won two-thirds of the parliament seats. The rest were shared among other parties. This way, fascists used democratic law to make Italy a one-party state.

In 1924, the PNF won the election with 65% of the votes. However, the United Socialist Party refused to accept this. Deputy Giacomo Matteotti publicly accused the PNF of cheating in the election and spoke out against the violence of the fascist Blackshirts. He was also writing a book to prove his claims. On June 10, 1924, Matteotti was killed by a group linked to the fascist party. Five men were arrested, and one, Amerigo Dumini, was sentenced to five years but served only eleven months and was freed. When the King supported Prime Minister Mussolini, the socialists left Parliament in protest, allowing the fascists to govern without opposition. At that time, killing opponents was not common. The Italian fascist leader usually dealt with opponents by arresting them and sending them to islands.

How Fascism Grew in Italy

Unhappiness with Nationalism

After World War I (1914–1918), Italy was a full partner with the Allied Powers. However, Italian nationalism felt Italy was cheated in the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye (1919). They believed the Allies stopped Italy from becoming a "Great Power." The PNF used this feeling to argue that fascism was the best way to govern Italy. They claimed that democracy, socialism, and liberalism had failed. The PNF took control of the Italian government in 1922, thanks to Mussolini's speeches and the political violence of his Blackshirt paramilitary groups.

At the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, the Allies forced Italy to give the Croatian port of Fiume (Rijeka) to Yugoslavia. This city was mostly Italian but not very important to nationalists until 1919. Also, Italy was left out of the secret wartime Treaty of London (1915). In this treaty, Italy had agreed to leave the Triple Alliance and join the Allies by declaring war on Germany and Austria-Hungary. In return, Italy was promised territories it claimed (see Italia irredenta) after the war.

In September 1919, the angry war hero Gabriele D'Annunzio responded by creating the Italian Regency of Carnaro. He made himself the leader (Duce) of this independent Italian state. He also created the Carta del Carnaro (Charter of Carnaro), a mix of right-wing and left-wing political ideas. This greatly influenced early Italian fascism. After the Treaty of Rapallo (1920), the Italian military removed D'Annunzio's Regency in December 1920. D'Annunzio was a nationalist, not a fascist. His style of "Politics as Theatre" (ceremonies, uniforms, speeches, and chanting) was adopted by Italian Fascism.

At the same time, Mussolini and many of his followers moved towards a form of revolutionary nationalism. They wanted to connect people not by class, but by nation. According to A. James Gregor, Mussolini came to believe that "Fascism was the only form of 'socialism' right for the 'proletarian nations' of the twentieth century." Enrico Corradini, an early influence on Mussolini, promoted the idea of proletarian nationalism. He wrote in 1910 that Italy was "the proletarian people compared to the rest of the world. Nationalism is our socialism." Mussolini later used similar words, calling fascist Italy during World War II the "proletarian nations that rise up against the rich."

Worker Unrest

Italian fascism combined ideas from both left-wing and right-wing policies. This helped them gain support from unhappy workers and farmers. Farmers especially disliked socialist ideas about collective farming. Mussolini, who used to be a socialist, used speeches to inspire and organize country and working-class people. He said, "We declare war on socialism, not because it is socialist, but because it has opposed nationalism." Also, to get money for their campaigns in 1920–1921, the National Fascist Party sought support from factory owners and landowners. They appealed to their fears of left-wing socialist and Bolshevik worker politics and strikes. Fascists promised a good business environment with stable labor, wages, and politics. The fascist Party was on its way to power.

Historian Charles F. Delzell reports: "At first, the fascist Revolutionary Party was mainly in Milan and a few other cities. They grew slowly between 1919 and 1920. Only after the fear caused by workers taking over factories in late summer 1920 did fascism become widespread." Factory owners started giving money to Mussolini after he changed his party's name and stopped supporting Lenin and the Russian Revolution. By late 1920, fascism spread to the countryside. It sought support from large landowners, especially in areas like Bologna and Ferrara, which were strongholds of the Left and often saw violence. Socialist and Catholic organizers of farm workers were attacked by fascist Blackshirt groups. This period saw the start of squadrismo (fascist squad actions) and nightly attacks on Socialist and Catholic labor offices. During this time, Mussolini's fascist groups also attacked the Church, killing priests and burning churches.

Fascism Takes Power

Italy's use of brave elite shock troops called the Arditi, starting in 1917, greatly influenced fascism. The Arditi were soldiers trained for violence. They wore unique black uniforms and fezzes. The Arditi formed a national group in November 1918, which had about twenty thousand young men by mid-1919. Mussolini appealed to the Arditi, and the Fascists' squadristi (squads), formed after the war, were based on the Arditi.

World War I left Italy with huge debts, high unemployment (made worse by thousands of soldiers returning home), social unrest with strikes, organised crime, and anarchist, socialist, and communist uprisings. When the elected Italian Liberal Party government could not control Italy, Mussolini took charge. He fought these problems with the Blackshirts, who were paramilitary groups of World War I veterans and former socialists. Prime Ministers like Giovanni Giolitti allowed the fascists to take the law into their own hands. The violence between socialists and the mostly self-organized squadristi militias, especially in the countryside, grew so much that Mussolini was pressured to call a truce for "reconciliation with the Socialists." Signed in early August 1921, Mussolini and the Italian Socialist Party (PSI) agreed to the Pact of Pacification. However, most fascist leaders immediately condemned this peace pact. The pact was officially rejected during the Third Fascist Congress in November 1921.

The Liberal government preferred fascist class collaboration over the Communist Party of Italy's class conflict. They feared the Communists might take over, like Vladimir Lenin's Bolsheviks did in the Russian Revolution of 1917. However, Mussolini had originally praised Lenin's October Revolution and called himself "Lenin of Italy" in 1919.

The Manifesto of the Fascist Struggle (June 1919) of the PFR laid out the political and philosophical ideas of fascism. The manifesto was written by national syndicalist Alceste De Ambris and Futurist leader Filippo Tommaso Marinetti. It had four sections, describing the movement's goals in politics, society, military, and finance.

By the early 1920s, about 250,000 people supported the fascist movement's fight against Bolshevism. In 1921, the fascists became the PNF and gained political acceptance when Mussolini was elected to the Chamber of Deputies in 1922. Although the Liberal Party stayed in power, the governments were short-lived, especially that of Prime Minister Luigi Facta, whose government was indecisive.

To remove the weak parliamentary democracy, Mussolini (with military, business, and liberal right-wing support) launched the PNF March on Rome (October 27–31, 1922). This was a coup d'état to remove Prime Minister Luigi Facta and take over the government of Italy. Their goals were to restore national pride, restart the economy, increase production with labor controls, remove economic business controls, and establish law and order. On October 28, while the "March" was happening, King Victor Emmanuel III withdrew his support for Prime Minister Facta. He then appointed PNF Leader Benito Mussolini as the sixth Prime Minister of Italy.

The March on Rome became a victory parade. Fascists believed their success was both revolutionary and traditional.

Economy Under Fascism

Until 1925, when liberal economist Alberto de' Stefani was removed from his job as Minister of Economics (1922–1925), Italy's coalition government managed to restart the economy and balance the national budget. Stefani created economic policies that followed classical liberalism. For example, inheritance, luxury, and foreign capital taxes were removed. Life insurance (1923) and state communication monopolies were privatized. During this coalition government, pro-business policies did not seem to conflict with the state funding banks and industries. Political scientist Franklin Hugh Adler called this period "Liberal-Fascism." This was a mixed, unstable time where the old liberal system still allowed different views, elections, free press, and the right for unions to strike. Liberal Party leaders and industrialists thought they could control Mussolini by making him head of a coalition government.

One of Mussolini's first actions as Prime Minister was to give 400 million lira to Gio. Ansaldo & C., a major engineering company. After the 1926 deflation crisis, banks like Banco di Roma and Banco di Napoli also received state funding. In 1924, a private company, Unione Radiofonica Italiana (URI), part of the Marconi company, was given the official radio-broadcast monopoly by the Italian fascist government. After fascism was defeated in 1944, URI became Radio Audizioni Italiane (RAI) and later RAI — Radiotelevisione Italiana when television started in 1954.

Since Italy's economy was mostly rural, agriculture was very important to fascist economic policies and propaganda. To increase Italy's grain production, the fascist government started protectionist policies in 1925, but these eventually failed (see the Battle for Grain).

From 1926, after the Pact of the Vidoni Palace and the Syndical Laws, businesses and workers were organized into 12 separate groups. All other groups were outlawed or absorbed. These organizations negotiated labor contracts for all their members, with the state acting as a mediator. The state tended to favor large industries over small ones, commerce, banking, agriculture, labor, and transport, even though each sector officially had equal representation. Pricing, production, and distribution were controlled by employer associations, not individual companies. Worker groups negotiated collective labor contracts that applied to all companies in a specific sector. Enforcing these contracts was difficult, and the large bureaucracy delayed solving labor disputes.

After 1929, the fascist government fought the Great Depression with huge public works programs. These included draining the Pontine Marshes, developing hydroelectricity, improving railways, and rearming the military. In 1933, the Istituto per la Ricostruzione Industriale (IRI – Institute for Industrial Reconstruction) was created to help failing companies. It soon controlled large parts of the national economy through government-linked companies, like Alfa Romeo. Italy's Gross National Product grew by 2%. Car production increased, especially for Fiat. The aeronautical industry also grew. Especially after the League of Nations put sanctions on Italy in 1936 for invading Ethiopia, Mussolini strongly supported farming and self-sufficiency. He called these his economic "battles" for Land, the Lira, and Grain. As Prime Minister, Mussolini even worked physically with laborers. This "politics as theatre" style, inherited from Gabriele D'Annunzio, created great propaganda images of Il Duce as a "Man of the People."

A year after the IRI was created, Mussolini boasted to his Chamber of Deputies: "Three-fourths of the Italian economy, industrial and agricultural, is in the hands of the state." As Italy continued to nationalize its economy, the IRI "became the owner not only of the three most important Italian banks, which were clearly too big to fail, but also of the lion's share of the Italian industries." During this time, Mussolini called his economic policies "state capitalism" and "state socialism." This was later described as "economic dirigisme," where the state has the power to direct economic production and resource allocation. By 1939, fascist Italy had the highest rate of state ownership of an economy in the world, apart from the Soviet Union. The Italian state "controlled over four-fifths of Italy's shipping and shipbuilding, three-quarters of its pig iron production, and almost half that of steel."

Relations with the Catholic Church

In the 19th century, the forces of Risorgimento (1815–1871) conquered Rome and took control from the Papacy. The Pope then saw himself as a "prisoner in the Vatican." In February 1929, Mussolini, as Italian Head of Government, solved the long-standing Church-State conflict called the Roman Question (La Questione romana). He signed the Lateran Treaty between the Kingdom of Italy and the Holy See. This treaty created the Vatican City microstate in Rome. With the treaty, the papacy recognized the state of Italy. In return, the Vatican City gained diplomatic recognition, land, religious education in all state schools in Italy, and 50 million pounds sterling. British wartime records confirmed that a Swiss company, Profima SA, was the Vatican's company. This company was accused during World War II of acting against Allied interests. Cambridge historian John F. Pollard wrote that this financial deal ensured the "papacy [...] would never be poor again."

Soon after the Lateran Treaty was signed, Mussolini was almost "excommunicated" because he was determined to stop the Vatican from controlling education. In response, the Pope protested Mussolini's "pagan worship of the state" and the "exclusive oath of obedience" that forced everyone to support fascism. Mussolini, who once said in his youth that "religion is a type of mental illness," "wanted to appear greatly favored by the Pope" while also being "subordinate to no one." Mussolini's widow wrote in her 1974 book that her husband was "basically not religious until the later years of his life."

Influence Outside Italy

The fascist government's model was very influential outside Italy. In the twenty-one years between the World Wars, many political scientists and philosophers looked to Italy for ideas. Mussolini's success in bringing law and order to Italy was praised by Winston Churchill, Sigmund Freud, George Bernard Shaw, and Thomas Edison. The fascist government fought organized crime and the Sicilian Mafia.

Italian fascism was copied by Adolf Hitler's Nazi Party, the Russian Fascist Organization, and Romanian and Dutch fascists. The Sammarinese Fascist Party set up an early fascist government in San Marino, and their ideas were basically Italian fascism. In the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, Milan Stojadinović created his Yugoslav Radical Union. They wore green shirts and Šajkača caps and used the Roman salute. Stojadinović also took the title of Vodja (Leader). In Switzerland, pro-Nazi Colonel Arthur Fonjallaz became a big admirer of Mussolini after visiting Italy in 1932. He supported Italy taking over Switzerland and received fascist foreign aid. Switzerland hosted two Italian political-cultural groups: the International Centre for Fascist Studies (CINEF) and the 1934 congress of the Action Committee for the Universality of Rome (CAUR). In Spain, the writer Ernesto Giménez Caballero in Genio de España (The Genius of Spain, 1932) called for Italy to annex Spain, with Mussolini leading an international Latin Roman Catholic empire. He later became closely linked with Falangism and stopped supporting Spain's annexation to Italy.

Key Thinkers of Italian Fascism

- Benito Mussolini

- Massimo Bontempelli

- Giuseppe Bottai

- Enrico Corradini

- Carlo Costamagna

- Julius Evola

- Enrico Ferri

- Giovanni Gentile

- Corrado Gini

- Agostino Lanzillo

- Curzio Malaparte

- Filippo Tommaso Marinetti

- Robert Michels

- Angelo Oliviero Olivetti

- Sergio Panunzio

- Giovanni Papini

- Giuseppe Prezzolini

- Alfredo Rocco

- Edmondo Rossoni

- Margherita Sarfatti

- Ardengo Soffici

- Ugo Spirito

- Giuseppe Ungaretti

- Gioacchino Volpe

Famous Fascist Slogans

- Me ne frego ("I don't care!"), the Italian fascist motto.

- Libro e moschetto, fascista perfetto ("Book and musket, perfect fascist").

- Tutto nello Stato, niente al di fuori dello Stato, nulla contro lo Stato ("Everything in the State, nothing outside the State, nothing against the State").

- Credere, obbedire, combattere ("Believe, Obey, Fight").

- Chi si ferma è perduto ("He who hesitates is lost").

- Se avanzo, seguitemi; se indietreggio, uccidetemi; se muoio, vendicatemi ("If I advance, follow me. If I retreat, kill me. If I die, avenge me"). This was borrowed from French Royalist General Henri de la Rochejaquelein.

- Viva il Duce ("Long live the Leader").

- La guerra è per l'uomo come la maternità è per la donna ("War is to man as motherhood is to woman").

- Boia chi molla ("Who gives up is a rogue"); "boia" means "executioner" but here means "scoundrel" or "villain." It can also be an exclamation of anger.

- Molti nemici, molto onore ("Many enemies, much Honor").

- È l'aratro che traccia il solco, ma è la spada che lo difende ("The plough cuts the furrow, but the sword defends it").

- Dux mea lux ("The Leader is my light"), a Latin phrase.

- Duce, a noi ("Duce, to us").

- Mussolini ha sempre ragione ("Mussolini is always right").

- Vincere, e vinceremo ("To win, and we shall win!").

See Also

- Anti-fascism

- Fascism

- Italian fascist states

- Kingdom of Italy (1922–1943; as a fascist state)

- Italian Social Republic (1943–1945)

- National Fascist Party

- Nazism

- Post–World War II anti-fascism

- Squadrismo

- Shōwa Statism

- Totalitarianism

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |