Giovanni Papini facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Giovanni Papini

|

|

|---|---|

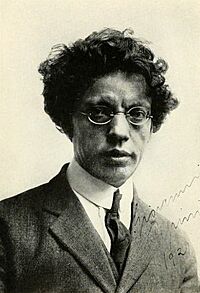

Papini in 1921

|

|

| Born | 9 January 1881 Florence, Italy |

| Died | 8 July 1956 (aged 75) Florence |

| Resting place | Cimitero delle Porte Sante |

| Pen name | Gian Falco |

| Occupation |

|

| Period | 1903–1956 |

| Genre | Prose poetry, fantasy, autobiography, travel literature, satire |

| Subject | Political philosophy, history of religion |

| Literary movement | Futurism Modernism |

| Notable works | A Man — Finished, Gog, The Story of Christ |

| Notable awards | Valdagno Prize (1951), Golden Quill Prize (1957) |

| Spouse | Giacinta Giovagnoli (1887–1958) |

| Children | 2 |

| Signature | |

Giovanni Papini (born January 9, 1881 – died July 8, 1956) was an Italian writer. He was a journalist, essayist, novelist, and poet. Papini was known for his strong opinions and writing style.

He was involved in new art movements like Futurism. Papini often changed his mind about politics and philosophy. He went from not believing in religion to becoming a Catholic. He also changed his views on war, first supporting it, then disliking it. Later in his life, he joined the Fascist political group, but he did not support Nazism.

Papini helped start magazines like Leonardo (1903) and Lacerba (1913). He believed writing should be active and bold. Even though he taught himself most things, he was a very important writer and editor. He played a big part in early Italian literary groups. He also helped bring new ideas from thinkers like Henri Bergson and William James to Italy.

His first big success was Il crepuscolo dei filosofi (The Twilight of the Philosophers) in 1906. His book Un uomo finito (A Finished Man) in 1913 was about his own life. After he died, his work was almost forgotten. But later, people like the writer Jorge Luis Borges said he was an "undeservedly forgotten" author.

Contents

Early Life and Learning

Giovanni Papini was born in Florence, Italy. His father sold furniture and had been a member of Giuseppe Garibaldi's Redshirts. Papini's mother secretly had him baptized. This was because his father was strongly against religion.

Papini mostly taught himself. He never went to university. His highest education was a teaching certificate. He had a quiet and lonely childhood. He disliked all beliefs and churches. He dreamed of writing an encyclopedia that would sum up all cultures.

From 1900 to 1902, he studied at the Istituto di Studi Superiori. He then taught for a year. From 1902 to 1904, he worked as a librarian. Papini was drawn to writing. In 1903, he started the magazine Il Leonardo. He wrote articles for it using the name "Gian Falco."

Through Il Leonardo, Papini introduced important thinkers to Italy. These included Kierkegaard, Peirce, and Friedrich Nietzsche. He also worked for Il Regno, a nationalist magazine. This magazine supported Italy's desire to expand its territories.

Papini met William James and Henri Bergson. These thinkers greatly influenced his early writings. He began publishing short stories and essays. In 1906, he wrote "Il Tragico Quotidiano" ("Everyday Tragic"). In 1907, he wrote "Il Pilota Cieco" ("The Blind Pilot"). He also published Il crepuscolo dei filosofi ("The Twilight of the Philosophers"). In this book, he argued against famous thinkers like Immanuel Kant and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel.

Papini declared that philosophy was "dead." He was interested in Futurism and other new art movements. In 1907, Papini married Giacinta Giovagnoli. They had two daughters.

Starting Magazines and New Ideas

After leaving Il Leonardo in 1907, Giovanni Papini started several other magazines. First, he published La Voce in 1908. Then, he started L'Anima with Giovanni Amendola. In 1913, just before World War I began, he launched Lacerba.

For three years, Papini was a writer for Mercure de France. He later became a literary critic for La Nazione. Around 1918, he created another magazine called La Vraie Italie. He worked on this with Ardengo Soffici.

Papini wrote many other books. His book Parole e Sangue ("Words and Blood") showed his early disbelief in religion. In 1912, he published his most famous work. This was the book about his own life, Un Uomo Finito (A Man — Finished).

In 1915, he published a collection of writings called Cento Pagine di Poesia. In this book, Papini compared himself to famous writers. These included Giovanni Boccaccio, William Shakespeare, and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. One critic said he was "one of the finest minds in the Italy of today." This critic also noted Papini's "refreshing independence."

In 1917, he published poems in a book called Opera Prima. In 1921, Papini announced he had become a Roman Catholic. He then published his book Storia di Cristo ("The Story of Christ"). This book became very popular around the world. It was translated into twenty-three languages.

After more poetry, he wrote the funny book Gog in 1931. He also wrote an essay called Dante Vivo ("Living Dante") in 1933.

Later Life and Legacy

In 1935, Papini became a teacher at the University of Bologna. The Fascist government approved his appointment. In 1937, Papini published his History of Italian Literature. He dedicated this book to Benito Mussolini, the leader of Italy. Papini was given important positions in schools. He especially focused on the Italian Renaissance. In 1940, his book was published in Nazi Germany.

Papini was also the vice president of the Europäische Schriftstellervereinigung. This was a group for European writers started in 1941. When the Fascist government fell in 1943, Papini went to a Franciscan religious house. He took the name "Fra' Bonaventura."

After World War II, Papini's reputation suffered. However, Catholic political groups supported him. He wrote about different topics, including a book about Michelangelo. He also continued to publish serious essays. He wrote articles for the newspaper Corriere della Sera. These were published in a book after he died.

Papini suffered from a disease that caused paralysis. He was blind in his last years. He died at age 75.

Some of Papini's writings were used by political groups. For example, his book Il Libro Nero (1951) contained made-up interviews. These were used against the artist Pablo Picasso.

Papini was admired by the mathematician Bruno de Finetti. He was also admired by Jorge Luis Borges. Borges said Papini had been "unjustly forgotten." He even included some of Papini's stories in his famous "Library of Babel."

Images for kids

-

"Caricature of Papini", by Carlo Carrà & Ardengo Soffici, from Broom, 1922.

-

Papini's grave in the Cimitero delle Porte Sante in Florence.

See also

In Spanish: Giovanni Papini para niños

In Spanish: Giovanni Papini para niños

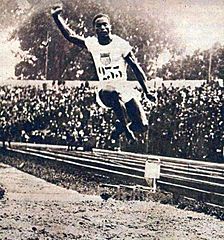

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |