Guglielmo Marconi facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

The Marchese

Guglielmo Marconi

|

|

|---|---|

Marconi in 1909

|

|

| Born |

Guglielmo Giovanni Maria Marconi

25 April 1874 |

| Died | 20 July 1937 (aged 63) Rome, Kingdom of Italy

|

| Nationality | Italian |

| Alma mater | University of Bologna |

| Known for | Radio |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Academic advisors | Augusto Righi |

| Signature | |

Guglielmo Marconi (born April 25, 1874 – died July 20, 1937) was an Italian inventor and electrical engineer. He is famous for creating the first practical radio wave-based wireless telegraph system. Because of his work, many people consider Marconi the inventor of radio.

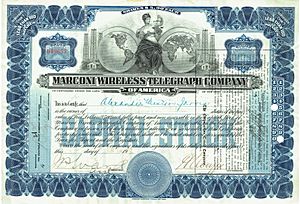

In 1909, he shared the Nobel Prize in Physics with Karl Ferdinand Braun. They received the award for their important work in developing wireless telegraphy. Marconi was also a smart businessman. He founded The Wireless Telegraph & Signal Company in the United Kingdom in 1897. This company later became known as the Marconi Company. In 1929, the King of Italy made Marconi a Marchese (a type of noble title). In 1931, he helped set up Vatican Radio for Pope Pius XI.

Marconi's Life Story

Growing Up

Guglielmo Giovanni Maria Marconi was born into a noble Italian family on April 25, 1874. His birthplace was the Palazzo Marescalchi in Bologna, Italy. His father, Giuseppe Marconi, was an Italian landowner. His mother, Annie Jameson, was from Ireland. Guglielmo had an older brother named Alfonso. He also had a stepbrother named Luigi. From ages two to six, Marconi lived in England with his mother and brother.

How He Learned

Marconi did not go to a regular school. Instead, he learned at home from private teachers. These tutors taught him chemistry, mathematics, and physics. When his family traveled to warmer places like Tuscany or Florence in winter, they hired more tutors for him.

A physics teacher named Vincenzo Rosa was an important mentor. Rosa taught Marconi about basic physics and new ideas about electricity. When Marconi was 18, he met Augusto Righi, a physicist at the University of Bologna. Righi allowed Marconi to attend university lectures. He also let Marconi use the university's lab and library.

Inventing Radio

From a young age, Marconi was very interested in science and electricity. In the early 1890s, he started working on "wireless telegraphy." This meant sending telegraph messages without using connecting wires. Many inventors had explored wireless ideas before, but none were very successful.

A key discovery came from Heinrich Hertz in 1888. Hertz showed that one could create and detect electromagnetic radiation. This radiation is now called radio waves. At first, scientists were more interested in radio waves as a scientific curiosity. They didn't see their potential for communication. They thought radio waves could only travel in a straight line, like light. This would limit their range to what you could see.

After Hertz died in 1894, more information about his discoveries was published. This included a demonstration by Oliver Lodge and an article by Augusto Righi. Righi's article made Marconi even more interested in using radio waves for wireless telegraphy. He noticed that other inventors weren't focusing on this idea.

Making Wireless Work

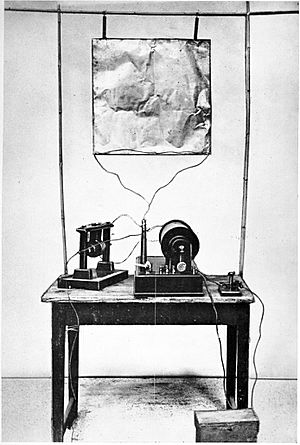

When he was 20, Marconi began experimenting with radio waves. He built much of his own equipment in his home's attic in Pontecchio, Italy. His butler, Mignani, helped him. Marconi improved on Hertz's experiments. He started using a device called a coherer. This device changed its electrical resistance when hit by radio waves.

In the summer of 1894, he built a storm alarm. It had a battery, a coherer, and an electric bell. The bell would ring when it picked up radio waves from lightning. In December 1894, Marconi showed his mother a radio transmitter and receiver. He pushed a button, and a bell rang across the room.

With his father's support, Marconi kept studying other physicists' work. He created portable transmitters and receivers that could work over long distances. He turned a lab experiment into a useful communication system. His system included:

- A simple spark-gap transmitter to create radio waves.

- A wire or metal sheet antenna placed high above the ground.

- A coherer receiver, improved to be more sensitive.

- A telegraph key to send short and long pulses, like Morse code.

- A telegraph register that recorded the Morse code signals on paper tape.

In the summer of 1895, Marconi moved his experiments outdoors. He tried different antennas. But even with improvements, his signals only traveled about half a mile. This was the distance Oliver Lodge had predicted.

A Big Breakthrough

A major breakthrough happened in the summer of 1895. Marconi found that he could send signals much farther by making his antenna taller. He also connected his transmitter and receiver to the ground. This was a technique used in wired telegraphy. With these changes, his system could send signals up to two miles and even over hills.

The new antenna sent out radio waves that could travel longer distances. Marconi realized that with more money and research, his device could send signals over even greater distances. He saw that it would be valuable for business and the military. Marconi's setup became the first complete and successful radio transmission system.

Marconi tried to get funding from the Italian government. But he didn't get a response. In 1896, he decided to go to Great Britain. He spoke fluent English. His family friend, Carlo Gardini, wrote a letter of introduction for him. The Italian Ambassador in London advised Marconi to get a patent before showing his work.

Marconi arrived in London in early 1896. He was 21 years old. He found support from William Preece, the Chief Electrical Engineer of the General Post Office. Marconi applied for his first patent for a radio wave communication system on June 2, 1896.

Amazing Demonstrations

Marconi showed his system to the British government in July 1896. He did more demonstrations, and by March 1897, he sent Morse code signals about six kilometers across Salisbury Plain. On May 13, 1897, Marconi sent the first wireless message over open sea. The message traveled about six kilometers across the Bristol Channel. It went from Flat Holm Island to Lavernock Point. The message simply said, "Are you ready."

William Preece was impressed. He introduced Marconi's work to the public in London. Marconi's work started getting international attention. In July 1897, he did tests for the Italian government. On March 27, 1899, he sent a transmission across the English Channel. It went from France to England.

Marconi set up an experimental base in Poole Harbour, England. He became friends with the van Raaltes, who owned Brownsea Island. Marconi later bought a steam yacht called the Elettra. He turned it into a floating laboratory for his experiments.

In December 1898, wireless communication was set up between the South Foreland lighthouse and a lightship. On March 17, 1899, the lightship sent the first wireless distress signal. It was for a ship that had run aground. The lighthouse received the message and called for help.

In late 1899, Marconi demonstrated his system in the United States. He was invited by The New York Herald newspaper. He covered the America's Cup yacht races. He installed wireless equipment on a passenger ship, the SS Ponce. Later, he installed equipment on the SS Saint Paul. On November 15, the Saint Paul became the first ocean liner to report its return to Britain by wireless. A newspaper called the Transatlantic Times was published on board. It had news from the Needles Station, received wirelessly.

Sending Signals Across the Ocean

Around 1900, Marconi wanted to send signals across the Atlantic Ocean. He wanted to compete with the transatlantic telegraph cables. In 1901, he set up a transmitting station in Ireland. He announced that a message was received in Signal Hill, Newfoundland, Canada, on December 12, 1901. This was a distance of about 2,200 miles. He used a kite-supported antenna to receive the signals. This was seen as a huge scientific step. However, some people were, and still are, doubtful about this claim. The signals were reported as faint and hard to hear.

To answer the doubters, Marconi planned a more organized test. In February 1902, he sailed from Great Britain on the SS Philadelphia. He carefully recorded signals sent daily from his station in England. He found that signals traveled much farther at night than during the day. During the day, signals only went about 700 miles. This was less than half the distance he claimed in Newfoundland. Even so, he proved that radio signals could travel hundreds of miles. This was important because some scientists thought they were limited to line-of-sight distances.

On December 17, 1902, a message from Marconi's station in Glace Bay, Canada, became the first radio message to cross the Atlantic from North America. In 1903, a station in South Wellfleet, Massachusetts, sent a message from U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt to King Edward VII of the United Kingdom. But sending consistent signals across the Atlantic was still difficult.

Marconi built powerful stations on both sides of the Atlantic to talk to ships at sea. In 1904, he started a service to send nightly news summaries to ships. A regular transatlantic radio service finally began on October 17, 1907.

The Titanic and Radio

The role of Marconi's wireless system in sea rescues made radio famous. This was especially true after the sinking of the RMS Titanic on April 15, 1912. The Titanic's radio operators worked for the Marconi Company. After the ship sank, survivors were rescued by the RMS Carpathia. The Carpathia received and decoded the SOS signal in 17 minutes.

When the Carpathia docked in New York, Marconi went aboard. He spoke with Harold Bride, the surviving operator. After this event, Marconi became even more recognized for his work. On June 18, 1912, Marconi testified about marine telegraphy at the inquiry into the Titanic's loss. Britain's Postmaster-General said, "Those who have been saved, have been saved through one man, Mr. Marconi... and his marvellous invention."

Later Radio Work

For many years, Marconi's companies kept using older spark-transmitter technology. This technology was only good for sending telegraph messages. It was not as efficient as newer continuous-wave transmissions. These newer methods could also send audio.

Later, around 1915, the company started working with continuous-wave equipment. In 1920, the first entertainment radio broadcasts in the United Kingdom happened at Marconi's factory in Chelmsford. Regular entertainment broadcasts began in 1922. This led to the creation of the BBC. In 1924, the Marconi Company helped create the Unione Radiofonica Italiana (now RAI).

Marconi's Final Years

In 1914, Marconi became a Senator in Italy. He was also made an Honorary Knight in the UK. During World War I, Italy joined the Allied side. Marconi was put in charge of the Italian military's radio service. He became a lieutenant in the army and a commander in the navy. In 1929, the King of Italy made him a marquess.

Marconi worked on developing microwave technology. He suffered several heart attacks in the years before his death. He died in Rome on July 20, 1937, at age 63, from a heart attack. Italy held a state funeral for him. As a tribute, shops on his street closed for national mourning. The next day, at the time of his funeral, radio transmitters worldwide observed two minutes of silence. His remains are in the Mausoleum of Guglielmo Marconi in Sasso Marconi, Italy.

In 1943, Marconi's yacht, the Elettra, was used by the German Navy. It was sunk by the RAF in 1944. After the war, parts of the wreckage were brought to Italy. They were later cut into pieces and given to Italian museums.

In 1943, the Supreme Court of the United States made a decision about Marconi's radio patents. The court said that some earlier patents by other inventors were valid. This decision did not say Marconi wasn't the first to achieve radio transmission. It just meant he couldn't claim ownership of certain parts of the technology.

His Family Life

Marconi married Beatrice O'Brien in 1905. They had three daughters: Degna, Gioia, and Lucia (who died as a baby). They also had a son, Giulio. In 1913, the Marconi family moved back to Italy.

Marconi later married Maria Cristina Bezzi-Scali in 1927. He became a devout member of the Catholic Church. Marconi and Maria Cristina had one daughter, Maria Elettra Elena Anna.

In 1931, Marconi personally introduced the first radio broadcast by a Pope, Pope Pius XI. He announced, "With the help of God... I have been able to prepare this instrument which will give to the faithful of the entire world the joy of listening to the voice of the Holy Father."

Political Involvement

Marconi joined the National Fascist Party in 1923. In 1930, the Italian leader Benito Mussolini appointed him President of the Royal Academy of Italy. This made Marconi a member of the Fascist Grand Council. Marconi held these important positions during a time of political change in Italy.

Marconi's Legacy

Archives

A large collection of Marconi's items is now held by the Museum of the History of Science in the UK. This collection includes artifacts, papers, books, and patents. An online catalog of the Marconi Archives was released in 2008.

Honors and Awards

- In 1901, he became a member of the American Philosophical Society.

- In 1903, he received the freedom of the City of Rome.

- In 1909, Marconi shared the Nobel Prize in Physics.

- In 1914, the King of Italy made Marconi a senator.

- In 1918, he received the Franklin Institute's Franklin Medal.

- In 1920, he was awarded the IEEE Medal of Honor.

- In 1931, he received the John Scott Medal.

- In 1934, he was awarded the Wilhelm Exner Medal.

- In 1974, Italy made a special coin to celebrate 100 years since Marconi's birth.

- In 1975, Marconi was added to the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

- In 1978, he was inducted into the NAB Broadcasting Hall of Fame.

- In 1988, the Radio Hall of Fame honored Marconi as a Pioneer.

- In 1990, the Bank of Italy issued a 2,000 Lire banknote with his picture.

- In 2001, Great Britain released a special £2 coin to celebrate 100 years of Marconi's first wireless communication.

- In 2009, Italy issued a special silver 10 Euro coin for the 100th anniversary of his Nobel Prize.

- In 2009, he was inducted into the New Jersey Hall of Fame.

- The Dutch radio academy gives out the Marconi Awards each year for great radio programs.

- The National Association of Broadcasters (US) gives out the annual NAB Marconi Radio Awards.

Tributes

- A monument to Marconi is in the Basilica of Santa Croce, Florence. His remains are in the Mausoleum of Guglielmo Marconi in Sasso Marconi, Italy. His old home next to the mausoleum is now the Marconi Museum (Italy).

- A sculpture of Guglielmo Marconi stands in Washington, D.C..

- A granite monument stands near Marconi's old wireless station in Cornwall, England. It remembers his first transatlantic transmission.

- Marconi Plaza Park in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, is named after him. It has a statue of Marconi.

Places and Organizations Named After Marconi

Outer Space

The asteroid 1332 Marconia is named in his honor. A large crater on the far side of the moon is also named after him.

Europe

Italy

- Bologna Guglielmo Marconi Airport in Bologna is named after him.

- Ponte Guglielmo Marconi is a bridge in Rome.

Oceania

Australia

- The Australian football (soccer) club Marconi Stallions is named after him.

North America

Canada

- The Marconi's Wireless Telegraph Company of Canada was created in 1903 by Guglielmo Marconi. It is now called CMC Electronics and Ultra Electronics.

- The Marconi National Historic Sites of Canada were created by Parks Canada. They honor Marconi's work in radio. The museum is in Glace Bay, Nova Scotia.

United States

California

- Marconi Conference Center and State Historic Park is the site of an old receiving station.

Hawaii

- Marconi Wireless Telegraphy Station on Oahu's North Shore was once the world's most powerful telegraph station.

Massachusetts

- Marconi Beach in Wellfleet, Massachusetts, is part of the Cape Cod National Seashore. It is near where he sent his first transatlantic wireless signal from the U.S.

New Jersey

- New Brunswick Marconi Station is now the Guglielmo Marconi Memorial Plaza in Somerset, NJ.

- Belmar Marconi Station is now the InfoAge Science History Center.

New York

- La Scuola d'Italia Guglielmo Marconi is a school on New York City's Upper East Side.

Pennsylvania

- Marconi Plaza, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, is a park named to honor Marconi.

Patents

British patents

- British patent No. 12,039 (1897) "Improvements in Transmitting Electrical impulses and Signals, and in Apparatus therefor".

- British patent No. 7,777 (1900) "Improvements in Apparatus for Wireless Telegraphy".

- British patent No. 10245 (1902)

- British patent No. 5113 (1904) "Improvements in Transmitters suitable for Wireless Telegraphy".

- British patent No. 21640 (1904) "Improvements in Apparatus for Wireless Telegraphy".

- British patent No. 14788 (1904) "Improvements in or relating to Wireless Telegraphy".

US patents

- U.S. Patent 586,193 "Transmitting electrical signals", filed December 1896, patented July 1897.

- U.S. Patent 624,516 "Apparatus employed in wireless telegraphy".

- U.S. Patent 627,650 "Apparatus employed in wireless telegraphy".

- U.S. Patent 647,007 "Apparatus employed in wireless telegraphy".

- U.S. Patent 647,008 "Apparatus employed in wireless telegraphy".

- U.S. Patent 647,009 "Apparatus employed in wireless telegraphy".

- U.S. Patent 650,109 "Apparatus employed in wireless telegraphy".

- U.S. Patent 650,110 "Apparatus employed in wireless telegraphy".

- U.S. Patent 668,315 "Receiver for electrical oscillations".

- U.S. Patent 676,332 "Apparatus for wireless telegraphy".

- U.S. Patent 757,559 "Wireless telegraphy system".

- U.S. Patent 760,463 "Wireless signaling system".

- U.S. Patent 763,772 "Apparatus for wireless telegraphy".

- U.S. Patent 786,132 "Wireless telegraphy".

- U.S. Patent 792,528 "Wireless telegraphy".

- U.S. Patent 884,986 "Wireless telegraphy".

- U.S. Patent 884,987 "Wireless telegraphy".

- U.S. Patent 884,988 "Detecting electrical oscillations".

- U.S. Patent 884,989 "Wireless telegraphy".

- U.S. Patent 924,560 "Wireless signaling system".

- U.S. Patent 935,381 "Transmitting apparatus for wireless telegraphy".

- U.S. Patent 935,382 "Apparatus for wireless telegraphy".

- U.S. Patent 935,383 "Apparatus for wireless telegraphy".

- U.S. Patent 954,640 "Apparatus for wireless telegraphy".

- U.S. Patent 997,308 "Transmitting apparatus for wireless telegraphy".

- U.S. Patent 1,102,990 "Means for generating alternating electric currents".

- U.S. Patent 1,226,099 "Transmitting apparatus for use in wireless telegraphy and telephony".

- U.S. Patent 1,271,190 "Wireless telegraph transmitter".

- U.S. Patent 1,377,722 "Electric accumulator".

- U.S. Patent 1,148,521 "Transmitter for wireless telegraphy".

- U.S. Patent 1,981,058 "Thermionic valve".

Reissued (US)

- U.S. Patent RE11,913 "Transmitting electrical impulses and signals and in apparatus, there-for".

See also

In Spanish: Guillermo Marconi para niños

In Spanish: Guillermo Marconi para niños

- History of radio

- Jagadish Chandra Bose

- List of people on stamps of Ireland

- List of covers of Time magazine during the 1920s – December 6, 1926

- Marconi's law