Friedrich Hölderlin facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Friedrich Hölderlin

|

|

|---|---|

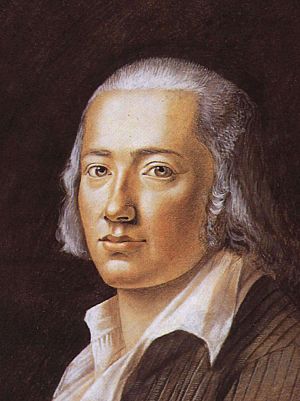

Hölderlin by Franz Carl Hiemer, 1792

|

|

| Born | Johann Christian Friedrich Hölderlin 20 March 1770 Lauffen am Neckar, Duchy of Württemberg, Holy Roman Empire |

| Died | 7 June 1843 (aged 73) Tübingen, Kingdom of Württemberg, German Confederation |

| Education | Tübinger Stift, University of Tübingen (1788–1793) University of Jena (1795) |

| Genre | Lyric poetry |

| Literary movement | Romanticism, German idealism |

| Notable works | Hyperion |

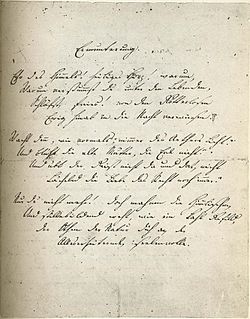

| Signature | |

|

|

Friedrich Hölderlin (born March 20, 1770 – died June 7, 1843) was an important German poet and philosopher. He is known as a key figure in German Romanticism, a time when artists focused on emotion and nature. He also influenced German Idealism, a major philosophical movement, especially through his friendships with thinkers like Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel and Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling.

Hölderlin was born in Lauffen am Neckar. His early life was marked by the loss of his father and stepfather. His mother wanted him to become a church minister. He studied at the Tübinger Stift, where he became close friends with Hegel and Schelling. After graduating in 1793, he decided not to join the church. Instead, he became a private teacher, also known as a tutor.

Later, he briefly attended the University of Jena and met other important thinkers. He continued working as a tutor but found it hard to become a successful poet. He faced many challenges, including mental health struggles. In 1806, he received care at a clinic. When he was thought to be incurable, a kind carpenter named Ernst Zimmer offered him a place to live. Hölderlin spent the last 36 years of his life in Zimmer's home in Tübingen, where he passed away in 1843 at age 73.

Hölderlin greatly admired Greek mythology and ancient Greek poets like Pindar and Sophocles. He blended ideas from Christianity and ancient Greece in his writings. The famous philosopher Martin Heidegger once said that Hölderlin was one of Germany's greatest poets and thinkers.

Contents

Hölderlin's Life Story

Early Years and Family

Johann Christian Friedrich Hölderlin was born on March 20, 1770, in Lauffen am Neckar. This town was part of the Duchy of Württemberg at the time. He was the first child of Johanna Christiana Heyn and Heinrich Friedrich Hölderlin. His father, who managed church property, died when Friedrich was only two years old. Friedrich and his sister, Heinrike, were then raised by their mother.

In 1774, his mother moved the family to Nürtingen. There, she married Johann Christoph Gok. Two years later, Johann Gok became the mayor (burgomaster) of Nürtingen. Hölderlin's half-brother, Karl Christoph Friedrich Gok, was born. Sadly, Johann Gok died in 1779 when he was only 30 years old.

School Days and Learning

Hölderlin started school in 1776. His mother hoped he would become a Lutheran church minister. To prepare for monastery entrance exams, he began extra lessons in Greek, Hebrew, Latin, and public speaking (rhetoric) in 1782. During this time, he became friends with Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, who was five years younger. Hölderlin often protected Schelling from older students. He also started playing the piano and enjoyed reading travel literature. He was especially interested in Georg Forster's book, A Voyage Round the World.

In 1784, Hölderlin entered the Lower Monastery in Denkendorf. This was the start of his official training for the church ministry. At Denkendorf, he discovered the poetry of Friedrich Schiller and Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock. He also began to write his own poems. In a letter from 1784, Hölderlin hinted that he had doubts about joining the church and worried about his own thoughts.

Hölderlin moved to the Higher Monastery at Maulbronn in 1786. Here, he formed a special friendship with Luise Nast, whose father managed the monastery. He started to question if he truly wanted to be a minister. In 1787, he wrote Mein Vorsatz (My Resolution), where he expressed his dream of becoming a great poet like Pindar and Klopstock. In 1788, he read Schiller's play Don Carlos because Luise Nast suggested it. Hölderlin later wrote to Schiller, saying that Carlos had been a "magic cloud" that protected him from seeing the harshness of the world too soon.

In October 1788, Hölderlin began studying theology at the Tübinger Stift. His classmates included Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Isaac von Sinclair, and Schelling. Some believe that Hölderlin introduced Hegel to ideas about the "unity of opposites" from the ancient philosopher Heraclitus. Hegel later used these ideas to develop his concept of dialectics. In 1789, Hölderlin ended his engagement with Luise Nast. He wrote to her that he wished her happiness with someone more worthy. He also wanted to switch to studying law but stayed at the Stift due to pressure from his mother.

Hölderlin, along with Hegel, Schelling, and other friends, strongly supported the French Revolution. Even though he disagreed with the violence of the Reign of Terror, he remained committed to the ideas of freedom and equality from 1789. His support for a republic influenced many of his famous works, such as Hyperion and The Death of Empedocles.

Becoming a Writer

After earning his master's degree in 1793, Hölderlin's mother expected him to become a minister. However, he did not feel satisfied with the church's teachings. Instead, he chose to work as a private tutor. In 1794, he met famous writers Friedrich Schiller and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. He then began writing his novel Hyperion, which is written as a series of letters. In 1795, he briefly attended the University of Jena, where he took classes with Johann Gottlieb Fichte and met Novalis.

Around 1797, a very important document called The Oldest Systematic Program of German Idealism was written. While it is in Hegel's handwriting, experts believe it might have been written by Hegel, Schelling, Hölderlin, or another person.

From 1796 to 1798, Hölderlin worked as a tutor in Frankfurt am Main. There, he formed a deep connection with Susette Gontard, the wife of his employer, a banker named Jakob Gontard. This friendship was very important to Hölderlin. When their close bond was discovered, Hölderlin was dismissed from his job. He then lived in Homburg from 1798 to 1800. He met Susette in secret once a month and tried to become a recognized poet. However, he struggled with money and had to rely on a small allowance from his mother. Being separated from Susette Gontard made him doubt himself and his abilities as a poet even more. He wanted to change German culture but felt he didn't have the influence he needed. From 1797 to 1800, he worked on a tragedy called The Death of Empedocles, which was never finished. He also wrote odes (a type of poem) in the style of ancient Greek poets.

Health Challenges and Later Years

In the late 1790s, Hölderlin began to experience serious mental health challenges. His condition worsened after his last meeting with Susette Gontard in 1800. After a short stay in Stuttgart in late 1800, where he likely worked on translating poems by Pindar, he found new tutoring jobs. He worked in Hauptwyl, Switzerland, and then for the Hamburg consul in Bordeaux, France, in 1802. His time in Bordeaux is remembered in his famous poem Andenken (Remembrance). However, after only a few months, he walked back home through Paris. He arrived in Nürtingen in late 1802, physically and mentally exhausted. He also learned that Susette Gontard had died from the flu around the same time.

While living with his religious mother in Nürtingen, Hölderlin combined his love for ancient Greece with Christian ideas. He tried to bring together old values with modern life. In his poem Brod und Wein (Bread and Wine), he suggests that Christ followed the Greek gods, bringing bread from the earth and wine from Dionysus. After two years in Nürtingen, Hölderlin was taken to the court of Homburg by Isaac von Sinclair. Sinclair found him a job as a court librarian. But in 1805, von Sinclair was accused of being a conspirator and faced trial. Hölderlin was also in danger but was declared mentally unable to stand trial. On September 11, 1806, Hölderlin was admitted to a clinic in Tübingen.

The clinic was part of the University of Tübingen. The poet Justinus Kerner, who was a medical student then, was assigned to look after Hölderlin. The next year, Hölderlin was discharged from the clinic because his condition was considered incurable. Doctors thought he would only live for three more years. However, a kind carpenter named Ernst Zimmer, who had read Hölderlin's novel Hyperion, took him in. Zimmer gave him a room in his house in Tübingen. This room was in an old city wall tower with a view of the Neckar river. This tower later became known as the Hölderlinturm (Hölderlin Tower) because he lived there for 36 years. His time in this building is often called the Turmzeit (Tower period).

Later Life and Passing

In the tower, Hölderlin continued to write poetry. His later poems were simpler and more formal than his earlier works. Over time, he became a minor tourist attraction. Curious travelers and people seeking autographs would visit him. He often played the piano or wrote short poems for his visitors. These poems were pure in their rhythm but seemed to lack strong emotion. However, some of them, like the famous Die Linien des Lebens (The Lines of Life), which he wrote for his caregiver Zimmer on a piece of wood, have a powerful beauty and have been set to music by many composers.

Hölderlin's own family did not support him financially. However, they successfully asked the state to pay for his care. His mother and sister never visited him, and his stepbrother only visited once. His mother died in 1828. His sister and stepbrother argued over his inheritance, claiming that too much money had been set aside for Hölderlin. They tried to overturn the will in court but failed. Neither of them attended his funeral in 1843. His childhood friends, Hegel (who had passed away earlier) and Schelling, had also long ignored him. The Zimmer family were his only mourners. His inheritance, which included money left to him by his father when he was two, had been kept from him by his mother. This money remained untouched and grew over time. He died a wealthy man, but he never knew it.

Hölderlin's Works

Hölderlin's poetry is now seen as one of the greatest achievements in German literature. However, during his lifetime, his work was not well known or understood. It became forgotten shortly after his death. His illness and quiet life made him disappear from the minds of people at the time. Even though some of his works were published by friends, they were mostly ignored for the rest of the 19th century.

Like his older fellow writers Goethe and Schiller, Hölderlin greatly admired ancient Greek culture. But for him, the Greek gods were not just old statues. They were powerful, life-giving presences, though sometimes frightening. Much later, the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche recognized Hölderlin as the first poet to truly understand the deeper, more mysterious side of Greek culture. Hölderlin combined this with the religious traditions of his home region, Swabia, creating a very unique spiritual experience. He believed that political change and an interest in ancient times, as well as Christianity and Paganism, should be brought together. He understood the Greek idea of a tragic fall, which he expressed powerfully in his poem "Hyperions Schicksalslied" ("Hyperion's Song of Destiny").

In his most important poems, Hölderlin often used a long, flowing style without rhymes. Along with these long hymns, odes, and elegies—which include "Der Archipelagus" ("The Archipelago"), "Brod und Wein" ("Bread and Wine"), and "Patmos"—he also wrote shorter, more precise poems. These included epigrams, couplets, and short works like the famous "Hälfte des Lebens" ("The Middle of Life").

After returning from Bordeaux, he finished some of his greatest poems. But he also kept going back to them, creating new and sometimes stranger versions. He would even layer different versions on the same piece of paper, which makes editing his works difficult. Some of these later versions and poems are incomplete, but they have amazing power. He sometimes seemed to think that even fragments, with unfinished lines, were complete poems. This constant revising and his stand-alone fragments were once seen as signs of his mental health struggles. However, they later greatly influenced poets like Paul Celan. During his years of illness, Hölderlin would sometimes write simple, rhymed four-line poems. These often had a childlike beauty. He would sign them with made-up names (most often "Scardanelli") and give them fake dates from past or future centuries.

How Hölderlin's Work Spread and Influenced Others

Hölderlin's main work published during his lifetime was his novel Hyperion, which came out in two parts (1797 and 1799). Various individual poems were also published but didn't get much attention. In 1799, he created a magazine called Iduna.

In 1804, his translations of Sophocles' plays were published. However, people generally made fun of them, saying they were unnatural and hard to understand. Critics thought this was because he tried to put Greek phrases directly into German. But in the 20th century, experts on translation like Walter Benjamin defended them. They showed how important these translations were as a new and influential way of translating poetry. "Der Rhein" and Patmos, two of his longest and most powerful hymns, appeared in a poetry calendar in 1808.

Wilhelm Waiblinger, who visited Hölderlin in his tower many times in 1822–23, wrote about him in his novel Phaëthon. Waiblinger said that an edition of Hölderlin's poems needed to be published. The first collection of his poetry was released by Ludwig Uhland and Christoph Theodor Schwab in 1826. However, Uhland and Schwab left out anything they thought might be "touched by insanity," which included many of Hölderlin's fragmented works. A copy of this collection was given to Hölderlin, but it was later stolen by someone looking for autographs. A second, larger edition with a biography appeared in 1842, the year before Hölderlin died.

It wasn't until 1913 that Norbert von Hellingrath published the first two volumes of what became a six-volume collection of Hölderlin's poems, prose, and letters. This was called the "Berlin Edition." For the first time, Hölderlin's hymn drafts and fragments were published. This made it possible to get a better understanding of his work from 1800 to 1807, which had been barely covered before. The Berlin edition and von Hellingrath's efforts led to Hölderlin finally getting the recognition he deserved after his death. As a result, since 1913, Hölderlin has been recognized as one of the greatest poets to write in the German language.

Norbert von Hellingrath joined the Imperial German Army when World War I began and was killed in action at the Battle of Verdun in 1916. The fourth volume of the Berlin edition was published after his death. The Berlin Edition was finished after the German Revolution of 1918 by Friedrich Seebass and Ludwig von Pigenot. The remaining volumes came out in Berlin between 1922 and 1923.

Even before the Berlin Edition started appearing, in 1912, Rainer Maria Rilke wrote his first two Duino Elegies. These poems were strongly inspired by Hölderlin's hymns and elegies. Rilke had met von Hellingrath a few years earlier and had seen some of the hymn drafts. The Duino Elegies marked the beginning of a new appreciation for Hölderlin's later work. While his hymns are hard to copy, they have become a powerful influence on modern poetry in German and other languages. They are sometimes called the very best of German lyric poetry.

The Berlin Edition was later replaced by the Stuttgart Edition (Grosse Stuttgarter Ausgabe), which began publishing in 1943 and finished in 1986. This project was much more careful in checking the texts than the Berlin Edition. It solved many questions about Hölderlin's unfinished and undated writings, which sometimes had several versions of the same poem with big differences. Meanwhile, a third complete edition, the Frankfurt Critical Edition, started publishing in 1975.

Hölderlin's hymn-like style, which relies on a true belief in the divine, creates a unique mix of Greek mythical figures and a spiritual connection to nature. This can seem both strange and appealing. His shorter and sometimes more fragmented poems have also had a wide influence on later German poets, starting with Georg Trakl. He also influenced the poetry of Hermann Hesse and Paul Celan. (Celan wrote a poem about Hölderlin called "Tübingen, January," which ends with the word Pallaksch—a word Hölderlin supposedly made up that sometimes meant "Yes" and sometimes "No.")

Hölderlin was also a thinker who wrote, in fragments, about poetry and philosophy. His theoretical works, like "Das Werden im Vergehen" ("Becoming in Dissolution") and "Urteil und Sein" ("Judgement and Being"), are insightful and important, even if they are sometimes difficult to understand. They bring up many of the same important questions that his Tübingen friends Hegel and Schelling also explored. While his poetry was never strictly "theory-driven," the study of some of his more challenging poems has led to deep philosophical discussions by thinkers like Martin Heidegger, Theodor Adorno, Jacques Derrida, Michel Foucault, and Alain Badiou.

Music Inspired by Hölderlin

Hölderlin's poetry has inspired many composers to create both vocal music and instrumental music.

- Vocal music

One of the earliest musical pieces based on Hölderlin's poetry is Schicksalslied by Johannes Brahms, which uses his poem Hyperions Schicksalslied. Other composers who set Hölderlin's poems to music include Ludwig van Beethoven (An die Hoffnung - Opus 32), Richard Strauss (Drei Hymnen), Benjamin Britten (Sechs Hölderlin-Fragmente), and György Ligeti (Three Fantasies after Friedrich Hölderlin). Carl Orff used Hölderlin's German translations of Sophocles in his operas Antigone and Oedipus der Tyrann. The Finnish melodic death metal band Insomnium has also used Hölderlin's verses in some of their songs.

- Instrumental music

Robert Schumann's piano suite Gesänge der Frühe was inspired by Hölderlin. Luigi Nono's string quartet Fragmente-Stille, an Diotima and parts of his opera Prometeo also draw inspiration from him. Paul Hindemith's First Piano Sonata is influenced by Hölderlin's poem Der Main. Hans Werner Henze's Seventh Symphony is partly inspired by Hölderlin's work.

Hölderlin in Cinema

- A 1981–1982 television drama called Untertänigst Scardanelli (The Loyal Scardanelli) was directed by Jonatan Briel.

- The 1985 film Half of Life is named after one of Hölderlin's poems. It explores the secret relationship between Hölderlin and Susette Gontard.

- In 1986 and 1988, Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub made two films, Der Tod des Empedokles and Schwarze Sünde. Both were filmed in Sicily and based on Hölderlin's drama Empedokles.

- German director Harald Bergmann has made several movies about Hölderlin, including Scardanelli (2000) and Passion Hölderlin (2003).

- A 2004 film, The Ister, is based on Martin Heidegger's 1942 lectures about Hölderlin's hymn "The Ister."

English Translations

- Some Poems of Friedrich Holderlin. Trans. Frederic Prokosch. (Norfolk, CT: New Directions, 1943).

- Alcaic Poems. Trans. Elizabeth Henderson. (London: Wolf, 1962; New York: Unger, 1963). ISBN: 978-0-85496-303-4

- Friedrich Hölderlin: Poems & Fragments. Trans. Michael Hamburger. (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1966; 4ed. London: Anvil Press, 2004). ISBN: 978-0-85646-245-0

- Friedrich Hölderlin, Eduard Mörike: Selected Poems. Trans. Christopher Middleton (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1972). ISBN: 978-0-226-34934-3

- Poems of Friedrich Holderlin: The Fire of the Gods Drives Us to Set Forth by Day and by Night. Trans. James Mitchell. (San Francisco: Hoddypodge, 1978; 2ed San Francisco: Ithuriel's Spear, 2004). ISBN: 978-0-9749502-9-7

- Hymns and Fragments. Trans. Richard Sieburth. (Princeton: Princeton University, 1984). ISBN: 978-0-691-01412-8

- Friedrich Hölderlin: Essays and Letters on Theory. Trans. Thomas Pfau. (Albany, NY: State University of New York, 1988). ISBN: 978-0-88706-558-3

- Hyperion and Selected Poems. The German Library vol.22. Ed. Eric L. Santner. Trans. C. Middleton, R. Sieburth, M. Hamburger. (New York: Continuum, 1990). ISBN: 978-0-8264-0334-6

- Friedrich Hölderlin: Selected Poems. Trans. David Constantine. (Newcastle upon Tyne: Bloodaxe, 1990; 2ed 1996) ISBN: 978-1-85224-378-4

- Friedrich Hölderlin: Selected Poems and Fragments. Ed. Jeremy Adler. Trans. Michael Hamburger. (London: Penguin, 1996). ISBN: 978-0-14-042416-4

- What I Own: Versions of Hölderlin and Mandelshtam. Trans. John Riley and Tim Longville. (Manchester: Carcanet, 1998). ISBN: 978-1-85754-175-5

- Holderlin's Sophocles: Oedipus and Antigone. Trans. David Constantine. (Newcastle upon Tyne: Bloodaxe, 2001). ISBN: 978-1-85224-543-6

- Odes and Elegies. Trans. Nick Hoff. (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan Press, 2008). ISBN: 978-0-8195-6890-8

- Hyperion. Trans. Ross Benjamin. (Brooklyn, NY: Archipelago Books, 2008) ISBN: 978-0-9793330-2-6

- Selected Poems of Friedrich Hölderlin. Trans. Maxine Chernoff and Paul Hoover. (Richmond, CA: Omnidawn, 2008). ISBN: 978-1-890650-35-3

- Essays and Letters. Trans. Jeremy Adler and Charlie Louth. (London: Penguin, 2009). ISBN: 978-0-14-044708-8

- The Death of Empedocles: A Mourning-Play. Trans. David Farrell Krell. (Albany, NY: State University of New York, 2009). ISBN: 978-0-7914-7648-2

- Selected Poems. Trans. Emery George (Kylix Press, 2011)

- Poems at the Window / Poèmes à la Fenêtre, Hölderlin's late contemplative poems, English and French rhymed and metered translations by Claude Neuman, trilingual German-English-French edition, Editions www.ressouvenances.fr, 2017

- Aeolic Odes / Odes éoliennes, English and French metered translations by Claude Neuman, trilingual German-English-French edition, Editions www.ressouvenances.fr, 2019 ; bilingual German-English edition : Edwin Mellen Press, 2022

- The Elegies / Les Elegies, English and French metered translations by Claude Neuman, trilingual German-English-French edition, Editions www.ressouvenances.fr, 2020 ; bilingual German-English edition : Edwin Mellen Press, 2022

See also

In Spanish: Friedrich Hölderlin para niños

In Spanish: Friedrich Hölderlin para niños

- The Oldest Systematic Program of German Idealism

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |