Georg Forster facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Georg Forster

FRS

|

|

|---|---|

Georg Forster at age 26, by J. H. W. Tischbein, 1781

|

|

| Born |

Johann George Adam Forster

27 November 1754 Nassenhuben, Pomeranian Voivodeship, Crown of the Kingdom of Poland

|

| Died | 10 January 1794 (aged 39) |

| Education | Saint Peter's School (Saint Petersburg), Warrington Academy |

| Known for | Founding modern travel literature |

| Spouse(s) | Therese Heyne |

| Children | Therese Forster |

| Parent(s) | Johann Reinhold Forster and Justina Elisabeth, née Nicolai |

| Awards | Fellow of the Royal Society, 1777 |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | natural history, ethnology |

| Institutions | Vilnius University, University of Mainz, Collegium Carolinum (Kassel) |

| Patrons | Catherine the Great |

| Influences | John Aikin, Carl Linnaeus |

| Influenced | Alexander von Humboldt |

| Author abbrev. (botany) | G.Forst. |

| Signature | |

Johann George Adam Forster, better known as Georg Forster (27 November 1754 – 10 January 1794), was a German geographer, naturalist, ethnologist, travel writer, journalist, and revolutionary. From a young age, he joined his father, Johann Reinhold Forster, on scientific trips. One of these was James Cook's second journey around the Pacific.

His book about that trip, A Voyage Round the World, greatly helped us understand the people of Polynesia. It is still an important book today. Because of this report, Forster became a member of the Royal Society at just 22 years old. He is now seen as one of the founders of modern scientific travel writing.

After his travels, Forster became a university professor. He taught natural history at the Collegium Carolinum in Kassel (1778–84). Later, he taught at the Academy of Vilna (Vilnius University) (1784–87). In 1788, he became the main librarian at the University of Mainz. During this time, he wrote essays on botany (plants) and ethnology (cultures). He also translated many books about travel and exploration, including James Cook's own travel diaries.

Forster was a key thinker during the Age of Enlightenment in Germany. He exchanged letters with many important people, including his friend Georg Christoph Lichtenberg. His ideas, travel stories, and personality influenced Alexander von Humboldt. Humboldt was a famous scientist in the 1800s who called Forster the founder of both comparative ethnology (the study of different cultures) and regional geography (the study of specific places).

When the French army took control of Mainz in 1792, Forster played a big part in creating the Mainz Republic. This was the first republic (a state governed by elected representatives) in Germany. In July 1793, while he was in Paris representing the new Mainz Republic, armies from Prussia and Austria took Mainz back. Forster was declared an outlaw. He could not return to Germany and was separated from his family. He died in Paris from an illness in early 1794, before he turned 40.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Georg Forster was born in Nassenhuben (now Mokry Dwór, Poland). This small village is near Danzig. He was born on 27 November 1754. Georg was the oldest of seven children. His father, Johann Reinhold Forster, was a Reformed Protestant pastor and scholar. His mother was Justina Elisabeth, née Nicolai.

From a young age, Georg loved studying nature. His father taught him biology, Latin, French, and religion. His father learned natural history from the books of Carl Linnaeus.

First Expedition to Russia

In 1765, Georg's father got a job from the Russian government. He was asked to check on new settlements near Saratov on the Volga River. These settlements were mostly for German colonists. Ten-year-old Georg went with his father on this long journey. They traveled about 4,000 kilometers (2,500 miles). They reached the Kalmyk Steppe and Lake Elton. Georg helped his father collect hundreds of plant samples. He also helped name and identify them.

From October 1765, Georg attended Saint Peter's School in St. Petersburg. His father was writing a report about the settlements. The report was critical of the local leader and the conditions. So, the Forsters left Russia without being paid.

Moving to England

After a sea trip from Kronstadt, they arrived in London on 4 October 1766. During the trip, Georg learned English and practiced Russian. Twelve-year-old Georg skillfully translated Lomonosov's history of Russia into English. He continued the history up to his own time. The printed book was given to the Society of Antiquaries in May 1767.

His father started teaching at Warrington Academy in June 1767. Georg stayed in London as an apprentice with a merchant. The rest of his family arrived in England in September 1767. In Warrington, Georg studied classic subjects and religion with John Aikin. He learned mathematics from John Holt. His father taught him French and natural history.

Around the World with Captain Cook

The Forsters moved back to London in 1770. There, Reinhold Forster made many scientific connections. He became a member of the Royal Society in 1772. After another scientist, Joseph Banks, dropped out, the British Admiralty invited Reinhold Forster to join James Cook's second expedition to the Pacific. This trip lasted from 1772 to 1775.

Georg Forster joined his father on this expedition. He was hired as a draughtsman (someone who makes drawings) to help his father. Johann Reinhold Forster's job was to write a scientific report about the discoveries after they returned.

The Journey Itself

They boarded HMS Resolution on 13 July 1772, in Plymouth. The ship first sailed to the South Atlantic. Then it went through the Indian Ocean and the Southern Ocean. Finally, it reached the islands of Polynesia and sailed around Cape Horn back to England. They returned on 30 July 1775.

During the three-year journey, the explorers visited many places. These included New Zealand, the Tonga islands, New Caledonia, Tahiti, the Marquesas Islands, and Easter Island. They sailed further south than anyone before them, almost reaching Antarctica. The journey proved that the idea of Terra Australis Incognita was wrong. This theory claimed there was a large, livable continent in the South.

Scientific Discoveries

Georg Forster, guided by his father, studied the zoology (animals) and botanics (plants) of the southern seas. He mostly drew pictures of animals and plants. But Georg also followed his own interests. This led him to explore geography and ethnology (the study of cultures) on his own. He quickly learned the languages of the Polynesian islands.

His reports about the people of Polynesia are highly respected today. He described the people of the southern islands with understanding and kindness. He did this mostly without judging them based on Western or Christian ideas.

Unlike Louis Antoine de Bougainville, who wrote about Tahiti a few years earlier, Forster gave a detailed picture of the South Pacific island societies. Bougainville's reports had started a romantic idea of the "noble savage." Forster, however, described different social structures and religions. He saw these on the Society Islands, Easter Island, and in Tonga and New Zealand. He believed this variety came from the different living conditions of the people.

At the same time, he noticed that the languages of these widely spread islands were similar. For example, he wrote about the people of the Nomuka islands (in Tonga). He said their languages, vehicles, weapons, clothes, and tattoos were just like those he had seen on Tongatapu. However, he also noted differences. He wrote that on Nomuka, "we could not observe any subordination among them." This was different from Tonga-Tabboo, where people showed great respect to their king.

The journey brought many scientific results. However, the relationship between the Forsters and Cook was often difficult. This was partly because of the elder Forster's temper. Cook also refused to allow more time for scientific observations. Because of his experiences with the Forsters, Cook did not allow scientists on his third journey.

Founder of Modern Travel Literature

The arguments continued after the journey. The question was who should write the official report of the travels. Lord Sandwich was willing to pay the promised money. But he was annoyed with Johann Reinhold Forster's first chapter. He tried to have it changed. However, Forster refused to have his writing corrected "like a theme of a School-boy."

As a result, Cook wrote the official report. The Forsters lost the right to write their own report and did not get paid for their work. During these talks, Georg Forster decided to write his own unofficial account of their travels.

A Voyage Round the World

In 1777, his book A Voyage Round the World in His Britannic Majesty's Sloop Resolution, Commanded by Capt. James Cook, during the Years, 1772, 3, 4, and 5 was published. This was the first book about Cook's second voyage. It came out six weeks before the official book. It was written for everyone to read.

The English version and his own German translation (published 1778–80) made the young author very famous. The poet Christoph Martin Wieland called the book the most important of his time. Even today, it is still one of the most important travel descriptions ever written. The book also had a big impact on German literature, culture, and science. It influenced scientists like Alexander von Humboldt and inspired many ethnologists later on.

Forster wrote clear and engaging German prose. It was not only scientifically correct but also exciting and easy to read. This was different from other travel books at the time. His book was more than just a collection of facts. It gave detailed, colorful, and reliable ethnographical information. This came from his careful and understanding observations. He often paused his descriptions to add philosophical thoughts about what he saw.

His main focus was always on the people he met. He wrote about their behavior, customs, habits, religions, and how their societies were organized. In A Voyage Round the World, he even included songs sung by the people of Polynesia. He provided both the lyrics and the music. The book is a very important source about the societies of the South Pacific before Europeans had a big influence.

Both Forsters also published descriptions of their South Pacific travels. These appeared in a Berlin magazine called Magazin von merkwürdigen neuen Reisebeschreibungen (Magazine of strange new travel accounts). Georg also translated "A Voyage to the South Sea, by Lieutenant William Bligh, London 1792" in 1791–93.

Forster at Universities

Publishing A Voyage Round the World brought Forster scientific fame across Europe. The respected Royal Society made him a member on 9 January 1777. He was not even 23 years old. He received similar honors from academies from Berlin to Madrid. However, these positions did not pay money.

In 1777, he traveled to Paris to talk with the American revolutionary Benjamin Franklin. In 1778, he went to Germany. He took a job as a Natural History professor at the Collegium Carolinum in Kassel. There, he met Therese Heyne, whose father was the classical scholar Christian Gottlob Heyne. Georg and Therese married in 1785, after he left Kassel. They had two children who survived, Therese Forster and Clara Forster. Their marriage was not happy. Therese later left him for Ludwig Ferdinand Huber. She became one of the first independent female writers in Germany.

From his time in Kassel, Forster regularly wrote to important thinkers of the Age of Enlightenment. These included Lessing, Herder, Wieland, and Goethe. He also helped the Carolinum in Kassel work with the University of Göttingen. His friend Georg Christoph Lichtenberg worked there. Together, they started and published a scientific and literary magazine. Forster's close friend, Samuel Thomas von Sömmering, arrived in Kassel soon after Forster. Both became involved with the Rosicrucians in Kassel.

By 1783, Forster felt that his involvement with the Rosicrucians was taking him away from real science. It also led him deeper into debt. So, Forster was happy to accept a job offer from the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. He became the Chair of Natural History at Vilnius University in 1784.

At first, he was well-received in Vilnius. But over time, he felt more and more alone. Most of his contacts were still with scientists in Germany. He had a notable discussion with Immanuel Kant about ideas of human groups. In 1785, Forster traveled to Halle. There, he submitted his thesis on South Pacific plants for a doctorate in medicine.

Back in Vilnius, Forster wanted to build a real natural history science center. But he could not get enough money from the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Also, his famous speech on natural history in 1785 was barely noticed. It was not printed until 1843. These events caused tension between him and the local community.

Eventually, he ended his contract six years early. Catherine II of Russia had offered him a place on a trip around the world. This was the Mulovsky expedition. It came with a high payment and a professor position in Saint Petersburg. This led to a conflict between Forster and the Polish scientist Jędrzej Śniadecki. However, the Russian offer was later taken back. Forster then left Vilnius. He settled in Mainz, where he became the head librarian of the University of Mainz. His friend Johannes von Müller had held this job before him.

Forster regularly published essays about current explorations. He continued to translate many books. For example, he wrote about Cook's third journey to the South Pacific. He also wrote about the Bounty expedition. He translated Cook's and Bligh's diaries from these journeys into German. From his years in London, Forster was in contact with Sir Joseph Banks. Banks started the Bounty expedition and was on Cook's first journey.

While at Vilnius University, Forster wrote an article called "Neuholland und die brittische Colonie in Botany-Bay." It was published in 1786. This essay discussed the future of the English colony founded in New South Wales in 1788.

He was also interested in indology (the study of India). One of the main goals of his failed expedition with Catherine II had been to reach India. He translated the Sanskrit play Shakuntala. He used a Latin version provided by Sir William Jones. This translation greatly influenced Johann Gottfried Herder. It also sparked German interest in the culture of India.

Views from the Lower Rhine

In the spring of 1790, Forster and the young Alexander von Humboldt began a long journey. They started from Mainz and traveled through the Southern Netherlands, the United Provinces, and England. They ended their trip in Paris.

Forster described his experiences from this journey in a three-volume book. It was called Ansichten vom Niederrhein, von Brabant, Flandern, Holland, England und Frankreich im April, Mai und Juni 1790. This means Views of the Lower Rhine, from Brabant, Flanders, Holland, England, and France in April, May and June 1790. The book was published from 1791 to 1794.

Goethe said about the book: "One wants, after one has finished reading, to start it over, and wishes to travel with such a good and knowledgeable observer." The book includes comments on the history of art. These comments were as important for art history as A Voyage Round the World was for ethnology. For example, Forster was one of the first writers to fairly describe the Gothic architecture of Cologne Cathedral. At that time, many people thought Gothic style was "barbarian." The book fit well with the early Romantic ideas in German-speaking Europe.

Forster's main interest, however, was again the social behavior of people. This was just like 15 years earlier in the Pacific. The uprisings in Flanders and Brabant and the revolution in France made him curious. His journey through these areas, along with the Netherlands and England, where people had many freedoms, helped him form his political views. From then on, he was a strong opponent of the ancien régime (the old system of government).

Like other German scholars, he welcomed the start of the revolution. He saw it as a clear result of the Enlightenment. As early as 30 July 1789, after hearing about the Storming of the Bastille, he wrote to his father-in-law. He said it was wonderful to see what philosophy had taught people and then achieved in the state. He wrote that teaching people about their rights was the surest way. The rest, he believed, would follow naturally.

Life as a Revolutionary

Founding the Mainz Republic

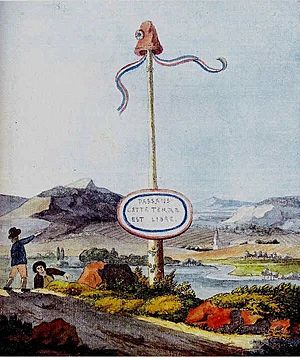

The French revolutionary army, led by General Custine, took control of Mainz on 21 October 1792. Two days later, Forster joined others in starting a Jacobin Club. It was called "Freunde der Freiheit und Gleichheit" ("Friends of Freedom and Equality"). This club met in the Electoral Palace.

From early 1793, he actively helped organize the Mainz Republic. This was the first republic on German soil. It was based on democratic ideas. It included areas on the left bank of the Rhine river, between Landau and Bingen. Forster became the vice-president of the republic's temporary government. He was also a candidate in the elections for the local parliament. This parliament was called the Rheinisch-Deutscher Nationalkonvent (Rhenish-German National Convention).

From January to March 1793, he was an editor for Die neue Mainzer Zeitung oder Der Volksfreund (The new Mainz newspaper or The People's Friend). The name was chosen to honor Marat's L'Ami du peuple (Friend of the People). In his first article, Forster wrote:

Die Pressefreiheit herrscht endlich innerhalb dieser Mauern, wo die Buchdruckerpresse erfunden ward.

The freedom of the press finally reigns within these walls where the printing press was invented.

This freedom did not last long. The Mainz Republic existed only until the French troops left in July 1793. This happened after the siege of Mainz.

Forster was not in Mainz during the siege. He and Adam Lux had been sent to Paris. They were representatives of the Mainz National Convention. Their job was to ask for Mainz to become part of the French Republic. Mainz could not exist as an independent state. The request was accepted. But it had no effect because Prussian and Austrian troops conquered Mainz. The old government was put back in place. Forster lost his library and collections. He decided to stay in Paris.

Death in Revolutionary Paris

An order from Emperor Francis II punished Germans who worked with the French revolutionary government. Because of this, Forster was declared an outlaw. He could not return to Germany. He had no way to earn a living. His wife had stayed in Mainz with their children and her later husband, Ludwig Ferdinand Huber.

Forster remained in Paris. At this time, the revolution in Paris had entered the Reign of Terror. This was a period of harsh rule by the Committee of Public Safety, led by Maximilien Robespierre. Forster saw the difference between the revolution's promises of happiness for everyone and its cruel reality. Unlike many other German supporters of the revolution, such as Friedrich Schiller, Forster did not give up his revolutionary ideals. He saw the events in France as a powerful force that could not be stopped. He believed it had to release its energy to avoid being even more destructive.

Before the Reign of Terror reached its peak, Forster died. He had a rheumatic illness. He passed away in his small attic apartment in Paris on 10 January 1794. He was 39 years old. At the time, he was planning a trip to India.

Views on Nations and Cultures

Forster had some Scottish family roots. He was born in Polish Royal Prussia, so he was a Polish subject by birth. He worked in Russia, England, Poland, and several German states of his time. He ended his life in France. He worked in different places and traveled a lot from a young age. He believed this, along with his scientific education based on Enlightenment ideas, gave him a broad view of different ethnic and national groups:

All peoples of the earth have equal claims to my good will ... and my praise and blame are independent of national prejudice.

He believed that all humans have the same abilities for reason, feelings, and imagination. But these basic parts are used in different ways and in different environments. This creates different cultures and civilizations. He thought it was clear that the culture on Tierra del Fuego was less developed than European culture. But he also admitted that life conditions there were much harder. This gave people very little chance to develop a higher culture. Because of these ideas, he is seen as a great example of 18th-century German cosmopolitanism (being a citizen of the world).

However, his private letters during his time in Vilnius showed some negative opinions about Poles. This was different from his public views on equality. These negative comments only became known after his death when his private letters and diaries were made public. Since Forster's published descriptions of other nations were seen as fair scientific observations, his private negative descriptions of Poland were sometimes used in Imperial and Nazi Germany. They were used to support the idea of German superiority. The spread of the "Polnische Wirtschaft" (Polish economy) stereotype likely came from his letters.

Forster's attitude sometimes caused conflicts with people from different nations. He was seen as too revolutionary and anti-national by Germans. He was proud and challenging in his dealings with Englishmen. He was seen as not caring enough about Polish science by Poles. And in France, he was seen as politically unimportant and ignored.

Legacy

After Forster's death, his works were mostly forgotten, except by experts. This was partly because he was involved in the French Revolution. However, how people viewed him changed with the politics of the times. Different periods focused on different parts of his work.

During the time of rising nationalism after the Napoleonic era, Germans saw him as a "traitor to his country." This overshadowed his work as a writer and scientist. This view grew even though the philosopher Karl Wilhelm Friedrich Schlegel wrote about Forster in the early 1800s:

Among all those authors of prose who are justified in laying claim to a place in the ranks of German classics, none breathes the spirit of free progress more than Georg Forster.

Some interest in Forster's life and revolutionary actions came back in the 1840s. This was during the liberal feelings leading up to the 1848 revolution. But he was largely forgotten in Germany under Wilhelm II and even more so in Nazi Germany. There, interest in Forster was limited to his private letters about Poland.

Interest in Forster started again in the 1960s in East Germany. There, he was seen as a champion of class struggle. The GDR research station in Antarctica, opened on 25 October 1987, was named after him. In West Germany, the search for democratic traditions in German history also led to a more balanced view of him in the 1970s. The Alexander von Humboldt foundation named a scholarship program for foreign scholars from developing countries after him.

His reputation as one of the first and most important German ethnologists is clear. His works are seen as crucial in making ethnology a separate science in Germany.

The items collected by Georg and Johann Reinhold Forster are now shown as the Cook-Forster-Sammlung (Cook–Forster Collection). This is part of the Sammlung für Völkerkunde (anthropological collection) in Göttingen. Another collection of items from the Forsters is on display at the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford.

Works

- A Voyage Round the World in His Britannic Majesty's Sloop Resolution, Commanded by Capt. James Cook, during the Years, 1772, 3, 4, and 5 (1777)

- Characteres generum plantarum, quas in Itinere ad Insulas Maris Australis, Collegerunt, Descripserunt, Delinearunt, annis MDCCLXXII-MDCCLXXV Joannes Reinoldus Forster et Georgius Forster (1775/76)

- De Plantis Esculentis Insularum Oceani Australis Commentatio Botanica (1786)

- Florulae Insularum Australium Prodromus (1786)

- Essays on moral and natural geography, natural history and philosophy (1789–97)

- Views of the Lower Rhine, Brabant, Flanders (three volumes, 1791–94)

- Georg Forsters Werke, Sämtliche Schriften, Tagebücher, Briefe, Deutsche Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin, G. Steiner et al. Berlin: Akademie 1958

- Werke in vier Bänden, Gerhard Steiner (editor). Leipzig: Insel 1965. ASIN: B00307GDQ0

- Reise um die Welt, Gerhard Steiner (editor). Frankfurt am Main: Insel, 1983. ISBN: 3-458-32457-7

- Ansichten vom Niederrhein, Gerhard Steiner (editor). Frankfurt am Main: Insel, 1989. ISBN: 3-458-32836-X

- Georg Forster, Briefe an Ernst Friedrich Hector Falcke. Neu aufgefundene Forsteriana aus der Gold- und Rosenkreuzerzeit, Michael Ewert, Hermann Schüttler (editors). Georg-Forster-Studien Beiheft 4. Kassel: Kassel University Press 2009. ISBN: 978-3-89958-485-1

See also

In Spanish: Georg Forster para niños

In Spanish: Georg Forster para niños

- European and American voyages of scientific exploration

- List of important publications in anthropology