Jean-Paul Marat facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Jean-Paul Marat

|

|

|---|---|

Jean-Paul Marat by Joseph Boze, 1793, Carnavalet Museum

|

|

| Born | 24 May 1743 |

| Died | 13 July 1793 (aged 50) |

| Cause of death | Assassination |

| Alma mater | University of St. Andrews, MD |

| Occupation | Journalist, politician, physician, scientist |

| Political party | Jacobin Club (1789–1790) Cordeliers Club (1790–1793) |

| Spouse(s) | fr: Simone Evrard |

| Parent(s) | Jean Mara, Louise Cabrol |

Jean-Paul Marat (born May 24, 1743 – died July 13, 1793) was a French writer, doctor, and scientist. He became famous for his strong role as a radical journalist and politician during the French Revolution. His writings were known for their fierce tone against the new leaders. He also strongly supported basic human rights for the poorest people. Marat was one of the most radical voices of the French Revolution.

Contents

Jean-Paul Marat's Early Life and Education

His Family Background

Jean-Paul Marat was born in Boudry, which is now a part of Switzerland. This was on May 24, 1743. He was the first of five children. His father, Jean Mara, was from Sardinia and had Spanish roots. His mother, Louise Cabrol, was from Geneva.

Marat's family was not rich, but they were comfortable. His father was well-educated but struggled to find a steady job. Marat said his father taught him to love learning. He felt lucky to have received a "very careful education" at home. His mother taught him strong morals and to care about society. Marat left home at 16 to study in France. He knew that people seen as outsiders had limited chances. His family moved to Neuchâtel in 1754, where his father became a tutor.

Marat's Education and Early Career

Marat first studied in Neuchâtel. Later, he moved to Paris to study medicine. He did not get a formal degree there. After moving to France, he changed his last name to "Marat."

He worked as a doctor without official qualifications after moving to London in 1765. He was very ambitious. Without a sponsor or degrees, he tried to become part of the intellectual world.

Marat's Early Writings

Political and Philosophical Works

Marat finished his first political book, Chains of Slavery, in 1774. In this book, Marat criticized parts of England's constitution. He thought they were unfair or like a dictator's rule. He spoke out against the King's power to influence Parliament. He also attacked limits on who could vote.

Chains of Slavery was inspired by Jean-Jacques Rousseau. It said that the common people, not a king, should have power. This book made him an honorary member of patriotic groups. These groups were in Berwick-upon-Tweed, Carlisle, and Newcastle.

Marat also published "A Philosophical Essay on Man" in 1773. He published "Chains of Slavery" in 1774.

Medical and Scientific Writings

When he returned to London, he published Enquiry into the Nature, Cause, and Cure of a Singular Disease of the Eyes. In 1776, Marat moved to Paris. He first stopped in Geneva to see his family.

In Paris, Marat became known as a very good doctor. He also gained the support of the Marquis de l'Aubespine. The Marquis was the husband of one of Marat's patients. This helped him get a job as a doctor for the bodyguard of the Comte d'Artois. This was Louis XVI's youngest brother. He started this job in June 1777. The job paid well, plus extra money.

Marat's Scientific Discoveries

Marat set up a lab in the Marquise de l'Aubespine's house. He used money he earned as a court doctor. He carefully described his experiments. He tried to explore all possible answers. Then he would rule out all but his own conclusion.

He wrote books about fire, heat, electricity, and light. He summarized his scientific ideas in Découvertes de M. Marat sur le feu, l'électricité et la lumière. This means Mr Marat's Discoveries on Fire, Electricity and Light. This book came out in 1779. He then published three more detailed books on each of his research areas.

Research on Fire

Marat's first big book about his experiments was Recherches Physiques sur le Feu. This means Research into the Physics of Fire. It was published in 1780. Official censors approved it.

This book described 166 experiments. They showed that fire was not a material element. Instead, he argued it was an "igneous fluid."

Discoveries on Light

In Marat's time, Newton's ideas about light and color were widely accepted. But Marat's goal in his second major book was to show that Newton was wrong in some key areas. This book was called Découvertes sur la Lumière, meaning Discoveries on Light.

Marat studied how light bends around objects. Newton believed white light broke into colors when it bent. Marat argued that colors were actually caused by diffraction. This happens when light spreads out as it passes through a small opening. He tried to show there are only three primary colors, not seven as Newton said.

Research on Electricity

Marat's third major work was Recherches Physiques sur l'Électricité. This means Research on the Physics of Electricity. It described 214 experiments. He was very interested in electrical attraction and repulsion. He believed repulsion was not a basic force of nature. He also wrote about lightning rods. He said pointed ones worked better than blunt ones. This book was approved by censors.

In April 1783, he left his court job. He then focused all his time on science. He also published shorter essays. These were about using electricity in medicine and about optics. He translated Newton's Opticks in 1787. This translation was still in print until recently. Benjamin Franklin visited him often.

Marat's Pre-Revolutionary Ideas

In 1780, Marat published his "favorite work." It was called Plan de législation criminelle. This book had many new ideas. He argued that society should provide basic needs like food and shelter. This was if it expected citizens to follow its laws. He also said the king was just the "first magistrate" of his people. He believed there should be one death penalty for everyone, no matter their social class. He also wanted each town to have a lawyer for the poor. He wanted independent criminal courts with twelve-person juries for fair trials.

Jean-Paul Marat and the French Revolution

In August 1789, Marat published La Constitution, ou Projet de déclaration des droits de l'homme et du citoyen. This was meant to influence France's new constitution. It was being discussed in the National Assembly. In this work, he used ideas from Montesquieu and Rousseau. He said that the power of the nation belongs to the people. He also stressed the need for a separation of powers. He supported a constitutional monarchy. He thought a republic would not work well in large nations. The National Assembly did not respond to Marat's work.

On September 12, 1789, Marat started his own newspaper. It was first called Publiciste parisien. Four days later, he changed its name to L'Ami du peuple ("The People's Friend"). Through this newspaper, he often attacked powerful groups in Paris. He saw them as plotting against the Revolution. These groups included the Commune, the Constituent Assembly, and government ministers.

Between 1789 and 1792, Marat often had to hide. Sometimes he hid in the Paris sewers. This likely made his skin condition worse. In January 1792, he married Simone Evrard. This was a common-law ceremony after he returned from London. She was the sister-in-law of his printer. She had lent him money and given him shelter many times.

As the Paris Commune gained more power, it created a Committee on Surveillance. Marat was one of its most important members. This committee decided to release some prisoners from jails if there was doubt about their guilt. Soon after, the September massacres began.

On September 3, the second day of the massacres, the Committee of Surveillance published a message. It asked people in other areas to defend Paris. It also asked them to remove those who opposed the Revolution. Marat wrote and signed this message. It was sent to other regions. It praised the actions in Paris as a model for others.

Marat was chosen for the National Convention in September 1792. He was one of 26 deputies from Paris. He did not belong to any specific party. When France was declared a Republic on September 22, Marat changed his newspaper's name. It became Le Journal de la République française ("Journal of the French Republic").

His view during the trial of King Louis XVI was unusual. He said it was unfair to accuse Louis of anything before he accepted the French Constitution of 1791. Even though he believed the king's death would help the people, he defended the King. He called him a "wise and respected old man."

On January 21, 1793, Louis XVI was guillotined. This caused political chaos. From January to May, Marat strongly argued with the Girondins. He believed they were secret enemies of republicanism. Marat's dislike and suspicion of the Girondins grew stronger. This led him to call for strong actions against them. He said France needed a leader, a "military Tribune." The Girondins fought back. They demanded that Marat be tried before the Revolutionary Tribunal.

After trying to avoid arrest for several days, Marat was finally put in prison. On April 24, he was brought before the Tribunal. He was accused of printing statements in his paper that called for widespread murder. He was also accused of wanting to stop the Convention. Marat strongly defended himself. He said he had no bad intentions against the Convention. Marat was found innocent of all charges. His supporters celebrated this decision.

Marat's Assassination

Marat was killed by Charlotte Corday. This happened while he was taking a special bath for his skin condition. After his death, Marat became a hero for the Jacobins. He was seen as a revolutionary martyr. This is shown in Jacques-Louis David's famous painting, The Death of Marat. Charlotte Corday was executed four days later, on July 17, 1793. During her trial, she said she acted alone. She stated she killed one man to help many others.

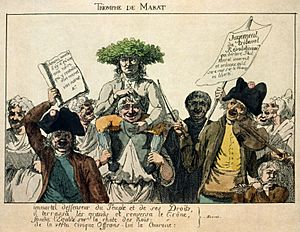

Images for kids

See Also

In Spanish: Jean-Paul Marat para niños

In Spanish: Jean-Paul Marat para niños