Pindar facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Pindar

|

|

|---|---|

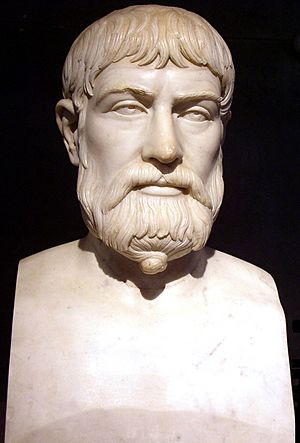

Pindar, Roman copy of Greek 5th century BC bust (Naples National Archaeological Museum, Naples)

|

|

| Native name |

Πίνδαρος

|

| Born | c. 518 BC Cynoscephalae, Boiotia |

| Died | c. 438 BC (aged approximately 80) Argos |

| Occupation | Lyric poet |

| Genre | Poetry |

Pindar (born around 518 BC, died around 438 BC) was a famous Ancient Greek poet from Thebes. He is known as one of the nine greatest lyric poets of ancient Greece, and his poems are the best preserved among them. People like Quintilian thought he was the best because of his amazing style and beautiful ideas.

Pindar was the first Greek poet to think deeply about what poetry is and what a poet's job should be. His poems show us the beliefs and values of Archaic Greece as it entered the Classical period. Like other poets of his time, he knew that life could be unpredictable. But he also strongly believed in what people could achieve with help from the gods. He famously wrote about this in one of his Victory Odes.

Contents

Pindar's Life Story

Learning About Pindar

We don't have many clear records about Pindar's life. Most of what we know comes from a few old writings, but many of these stories might not be completely true. Scholars today often look at Pindar's own poems, especially his victory odes, to learn about his life. These poems sometimes mention historical events that help us figure out when they were written.

However, it's tricky to use his poems as a diary. For a long time, experts thought his poems showed his personal thoughts. But then, a scholar named Elroy Bundy suggested that the odes were more like public speeches meant to praise people and communities. So, we still don't know a lot about Pindar's personal life.

Growing Up and Becoming a Poet

Pindar was born around 518 BC in a village called Cynoscephalae, near Thebes. There's a story that when he was young, a bee stung him on the mouth. People said this was why his poems were as sweet as honey!

He started writing poems when he was about 20 years old. His first big poem was a victory ode for a powerful family in Thessaly. Pindar studied poetry in Athens and even got some helpful advice from another poet named Corinna.

Pindar During the Persian Wars

Pindar's early career happened during the Greco-Persian Wars. These were big wars between the Greeks and the Persian Empire. When Pindar was almost 40, his hometown of Thebes was taken over by the Persian general Mardonius. Many Theban leaders died in the Battle of Plataea. Pindar might have spent some of this time in Aegina.

He also became good friends with a Sicilian prince named Thrasybulus, which later led to Pindar visiting Sicily.

Pindar's Middle Years

Pindar sometimes used his poems to help his friends. For example, he wrote two odes for King Arcesilas of Cyrene in 462 BC, asking for a friend named Demophilus to be allowed to return from exile. Pindar was proud of his own family history, which he shared with the king. This family was important in many parts of the Greek world. Being part of this family might have helped Pindar become a successful poet.

In 470 BC, Pindar wrote a poem for Hieron, a powerful ruler in Sicily. In this poem, Pindar celebrated Greek victories against foreign invaders, like the Athenians and Spartans beating the Persians. However, his hometown, Thebes, had actually sided with the Persians, so they weren't happy about his praise for Athens. The Theban authorities even fined him! But the Athenians reportedly paid his fine and gave him more money.

Pindar wrote the music and planned the dances for his victory odes. He traveled all over the Greek world to train performers and present his poems. He visited major festivals like the Olympic Games, and also places like Sicily, Macedonia, and Africa. Other poets competed with him for the favor of wealthy patrons. Pindar sometimes wrote about these rivalries in his poems.

Pindar's Later Years and Death

As Pindar grew older, his fame drew him into Greek politics. His home city, Thebes, was a rival of Athens. Even so, Pindar never openly criticized the Athenians in his poems, though sometimes his words hinted at it.

One of his last poems suggests he lived near a shrine and kept some of his wealth there. He also mentioned receiving a prophecy from a long-dead prophet.

We don't know much about Pindar's wife or son, only their names. A story says that about ten days before he died, the goddess Persephone appeared to him. She complained that he had never written a hymn for her and said he would come to her soon to compose one.

Pindar lived to be about 80 years old. He died around 438 BC while at a festival in Argos. His daughters, who were good at music, brought his ashes back home to Thebes.

Pindar's Legacy After Death

Pindar's house in Thebes became a famous landmark. Later, when Alexander the Great destroyed Thebes in 335 BC, he ordered Pindar's house to be left untouched. This was because Alexander appreciated Pindar's poems that praised his ancestor, Alexander I of Macedon.

At Delphi, where Pindar had been chosen as a priest of Apollo, priests would show an iron chair where he used to sit during a festival. Every night, they would say, "Let Pindar the poet go unto the supper of the gods!"

Pindar's Ideas and Beliefs

Pindar often wrote about his beliefs in his poems. He was one of the few ancient Greek poets to talk so much about the meaning of his art. He strongly supported choral poetry (poems sung by a group) when it was becoming less popular. He believed it showed the feelings and ideas of the Greek noble families.

His poems often connect gods, heroes, and people. He even wrote about the dead as if they were still listening.

Pindar's view of the gods was traditional and respectful. He never showed gods in a way that made them seem unimportant. He saw gods as powerful beings who protected their rights. He believed that people could be like gods if they reached their full potential, as their talents were gifts from the gods. When Pindar honored successful people, he was also honoring the gods.

He didn't have one clear idea about life after death, which was common at the time. But for Pindar, gaining glory and lasting fame was the best way to show a life well-lived. He believed that even for the best people, luck could change, so it was important to be humble in success and brave in hard times.

Pindar believed that while the Muses (goddesses of inspiration) gave him ideas, it was his job to use his own wisdom and skill to shape those ideas into poems. He saw himself as having a special calling, like a prophet. He thought lesser poets were like "ravens" compared to his "eagle," and their art was common, while his was magical.

Pindar's Works

Pindar was very creative, but he didn't invent new types of poems. Instead, he used the existing types in new ways. For example, in one of his victory odes, he said he invented a new way of playing music with a lyre, flute, and human voice all together.

He wrote in a special literary language that used a lot of the Doric dialect, mixed with other dialects. Scholars at the Library of Alexandria collected his poems into 17 books, organized by type:

- 1 book of hymns (songs of praise to gods)

- 1 book of paeans (songs of thanks or healing)

- 2 books of dithyrambs (wild, emotional songs for Dionysus)

- 2 books of processionals (songs for parades)

- 3 books of songs for maidens

- 2 books of songs for light dances

- 1 book of songs of praise

- 1 book of laments (sad songs for the dead)

- 4 books of victory odes (songs celebrating athletic wins)

Most of these books only survive in small pieces or quotes from other ancient writers. Only the victory odes are still complete today. Even the fragments show how complex his thoughts and language were.

His dithyrambs, for example, were full of strong religious feeling, showing the wild spirit of Dionysus. In one of these, written for the Athenians to be sung in spring, he described the energy of the world coming back to life:

|

φοινικοεάνων ὁπότ' οἰχθέντος Ὡρᾶν θαλάμου |

phoinikoeánōn hopót' oikhthéntos Hōrân thalámou |

When the room of the scarlet-clothed Hours opens |

Victory Odes

Almost all of Pindar's victory odes celebrate wins by athletes in major Greek festivals, like the Olympian Games. These festivals were very important to the Greek noble families. Winning at these events brought huge fame and honor, much more than winning a sports event today. Pindar's odes capture the glory of these victories. He wrote:

-

-

-

-

- If ever a man strives

-

- With all his soul's endeavour, sparing himself

- Neither expense nor labour to attain

- True excellence, then must we give to those

- Who have achieved the goal, a proud tribute

-

- Of lordly praise, and shun

- All thoughts of envious jealousy.

-

- To a poet's mind the gift is slight, to speak

- A kind word for unnumbered toils, and build

- For all to share a monument of beauty. (Isthmian I, antistrophe 3)

-

-

His victory odes are divided into four groups, named after the main festivals: Olympian, Pythian, Isthmian, and Nemean Games. Most of these odes were written for young men who had won athletic contests. Sometimes, he celebrated older victories or wins from smaller games, using them as a way to talk about other achievements. For example, Pythian 3 was written to comfort a ruler named Hieron, who was sick, even though it mentioned an old victory of his.

Pindar's Poetic Style

Pindar's poetry has a very unique style. His poems often start with a grand opening, perhaps calling out to a god or a place. He used rich, descriptive language and colorful words. His sentences could be very short and packed with meaning, sometimes making them hard to understand. He used unusual words, and his ideas sometimes seemed to jump around. This style can be puzzling but also makes his poems very vivid and memorable.

One scholar said Pindar's power came from "a splendor of phrase and imagery that suggests the gold and purple of a sunset sky." Another described his style as "a burning glow which darted out a shower of brilliant images."

Pindar's way of telling myths was also special. He often changed traditional stories because his audience already knew them. This allowed him to focus on surprising effects. He might tell events in reverse order or in a circular pattern. Myths helped him explore his main themes, like how humans relate to the gods and the limits of human life. He sometimes edited myths if they showed gods in a bad light, saying things like, "To insult the gods is a fool's wisdom." His myths were often dramatic, with big, symbolic elements like the sea, sky, or fire.

How Pindar's Odes Are Built

Pindar's odes usually begin by calling upon a god or the Muses. Then, he praises the winner of the contest, and often their family and hometown. After that, he tells a myth, which is usually the longest part of the poem. This myth teaches a lesson and connects the poet and audience to the world of gods and heroes. The ode usually ends with more praise, perhaps for the winner's coaches or relatives who also won contests, and with hopes for future success. He rarely described the actual athletic event in detail, but he often mentioned the hard work it took to win.

Most of Pindar's odes have a three-part structure. This means the stanzas are grouped in threes. Each group has two stanzas that are the same length and rhythm (called 'strophe' and 'antistrophe'), and a third stanza (called an 'epode') that is different but completes the musical flow. Some shorter odes have just one of these three-part units, while the longest has thirteen. Seven of his odes are simpler, with each stanza being the same length and rhythm. These simpler odes might have been for victory marches, while the three-part ones were for choral dances.

Pindar's rhythms were complex, not simple and repetitive like many modern poems. This adds to the feeling of depth in his work.

Timeline of Victory Odes

This table shows the estimated dates for Pindar's victory odes. The date of a victory isn't always when the poem was written, but it helps us understand the timeline of his career.

| Date (BC) |

Ode | Victor | Event | Focusing myth |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 498 | Pythian 10 | Hippocles of Thessaly | Boy's long foot-race | Perseus, Hyperboreans |

| 490 | Pythian 6 (M) | Xenocrates of Acragas | Chariot-race | Antilochus, Nestor |

| 490 | Pythian 12 (M) | Midas of Acragas | Flute-Playing | Perseus, Medusa |

| 488 (?) | Olympian 14 (M) | Asopichus of Orchomenus | Boys' foot-race | None |

| 486 | Pythian 7 | Megacles of Athens | Chariot-race | None |

| 485 (?) | Nemean 2 (M) | Timodemus of Acharnae | Pancration | None |

| 485 (?) | Nemean 7 | Sogenes of Aegina | Boys' Pentathlon | Neoptolemus |

| 483 (?) | Nemean 5 | Pythias of Aegina | Youth's Pancration | Peleus, Hippolyta, Thetis |

| 480 | Isthmian 6 | Phylacides of Aegina | Pancration | Heracles, Telamon |

| 478 (?) | Isthmian 5 | Phylacides of Aegina | Pancration | Aeacids, Achilles |

| 478 | Isthmian 8 (M) | Cleandrus of Aegina | Pancration | Zeus, Poseidon, Thetis |

| 476 | Olympian 1 | Hieron of Syracuse | Horse-race | Pelops |

| 476 | Olympians 2 & 3 | Theron of Acragas | Chariot-race | 2. Isles of the Blessed 3. Heracles, Hyperboreans |

| 476 | Olympian 11 | Agesidamus of Epizephyrian Locris | Boys' Boxing Match | Heracles, founding of Olympian Games |

| 476 (?) | Nemean 1 | Chromius of Aetna | Chariot-race | Infant Heracles |

| 475 (?) | Pythian 2 | Hieron of Syracuse | Chariot-race | Ixion |

| 475 (?) | Nemean 3 | Aristocleidas of Aegina | Pancration | Aeacides, Achilles |

| 474 (?) | Olympian 10 | Agesidamus of Epizephyrian Locris | Boys' Boxing Match | None |

| 474 (?) | Pythian 3 | Hieron of Syracuse | Horse-race | Asclepius |

| 474 | Pythian 9 | Telesicrates of Cyrene | Foot-race in armour | Apollo, Cyrene |

| 474 | Pythian 11 | Thrasydaeus of Thebes | Boys' short foot-race | Orestes, Clytemnestra |

| 474 (?) | Nemean 9 (M) | Chromius of Aetna | Chariot-race | Seven against Thebes |

| 474/3 (?) | Isthmian 3 & 4 | Melissus of Thebes | Chariot race & pancration | 3.None 4.Heracles, Antaeus |

| 473 (?) | Nemean 4 (M) | Timisarchus of Aegina | Boys' Wrestling Match | Aeacids, Peleus, Thetis |

| 470 | Pythian 1 | Hieron of Aetna | Chariot-race | Typhon |

| 470 (?) | Isthmian 2 | Xenocrates of Acragas | Chariot-race | None |

| 468 | Olympian 6 | Agesias of Syracuse | Chariot-race with mules | Iamus |

| 466 | Olympian 9 | Epharmus of Opous | Wrestling-Match | Deucalion, Pyrrha |

| 466 | Olympian 12 | Ergoteles of Himera | Long foot-race | Fortune |

| 465 (?) | Nemean 6 | Alcimidas of Aegina | Boys' Wrestling Match | Aeacides, Achilles, Memnon |

| 464 | Olympian 7 | Diagoras of Rhodes | Boxing-Match | Helios and Rhodos, Tlepolemus |

| 464 | Olympian 13 | Xenophon of Corinth | Short foot-race & pentathlon | Bellerophon, Pegasus |

| 462/1 | Pythian 4 & 5 | Arcesilas of Cyrene | Chariot-race | 4.Argonauts 5.Battus |

| 460 | Olympian 8 | Alcimidas of Aegina | Boys' Wrestling-Match | Aeacus, Troy |

| 459 (?) | Nemean 8 | Deinis of Aegina | Foot-race | Ajax |

| 458 (?) | Isthmian 1 | Herodotus of Thebes | Chariot-race | Castor, Iolaus |

| 460 or 456 (?) | Olympian 4 & 5 | Psaumis of Camarina | Chariot-race with mules | 4.Erginus 5.None |

| 454 (?) | Isthmian 7 | Strepsiades of Thebes | Pancration | None |

| 446 | Pythian 8 | Aristomenes of Aegina | Wrestling-Match | Amphiaraus |

| 446 (?) | Nemean 11 | Aristagoras of Tenedos | Inauguration as Prytanis | None |

| 444 (?) | Nemean 10 | Theaius of Argos | Wrestling-Match | Castor, Pollux |

Pindar's Influence and Legacy

Pindar's unique style influenced many later poets.

- The famous Alexandrian poet Callimachus was very interested in Pindar's original ideas. His important work Aetia included a poem celebrating a chariot victory, written in a style that reminded people of Pindar.

- The ancient Greek epic poem Argonautica, by Apollonius Rhodius, was also influenced by Pindar's style and his use of short stories within a larger narrative.

- After the Roman poet Horace published his Odes, there was a trend for poems written in Pindar's style. These were called Pindarics, even though they didn't always perfectly match Pindar's complex structure.

- Pindar's poems were widely read and copied during the Byzantine Era.

- For the modern Olympic Games, poets have sometimes been asked to write "Pindaric Odes" to celebrate the events, just like Pindar did in ancient times.

Horace's Tribute to Pindar

The Roman poet Quintus Horatius Flaccus greatly admired Pindar's style. He described it in one of his poems, saying that anyone who tries to copy Pindar is like someone trying to fly with wax wings, doomed to fall. He compared Pindar's poetry to a powerful river rushing down a mountain:

|

Pindarum quisquis studet aemulari, |

Julus, whoever tries to rival Pindar, |

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Píndaro para niños

In Spanish: Píndaro para niños

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |