Friedrich Schleiermacher facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

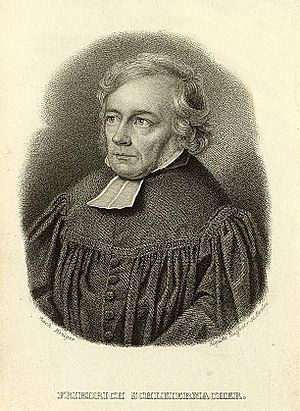

Friedrich Schleiermacher

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Friedrich Daniel Ernst Schleiermacher

21 November 1768 Breslau, Prussian Silesia, Kingdom of Prussia

|

| Died | 12 February 1834 (aged 65) Berlin, Province of Brandenburg, Kingdom of Prussia

|

| Alma mater | University of Halle (1787–90) |

| Era | 18th-/19th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | German Idealism Jena Romanticism Berlin Romanticism Romantic hermeneutics Methodological hermeneutics |

| Institutions | University of Halle (1804–07) University of Berlin (1810–34) |

| Notable students | August Böckh Friedrich Adolf Trendelenburg |

|

Main interests

|

Theology, psychology, New Testament exegesis, ethics (both philosophic and Christian), dogmatic and practical theology, dialectics (logic and metaphysics), politics |

|

Notable ideas

|

Hermeneutics as a cyclical process Socratic problem |

|

Influences

|

|

|

Influenced

|

|

Friedrich Daniel Ernst Schleiermacher (German: [ˈfʁiːdʁɪç ˈʃlaɪɐˌmaxɐ]; 21 November 1768 – 12 February 1834) was an important German theologian, philosopher, and biblical scholar. He is famous for trying to bring together the new ideas of the Enlightenment with traditional Protestant Christian beliefs.

Schleiermacher also played a big role in developing "higher criticism," which is a way of studying the Bible using historical and literary methods. His work also helped create the modern field of hermeneutics, which is the study of how we understand texts. Many people call him the "Father of Modern Liberal Theology" because of his huge impact on Christian thought. He was also a key leader in German Romanticism, a movement that focused on emotion and imagination.

Contents

About Schleiermacher's Life

Early Years and Education

Friedrich Schleiermacher was born in Breslau, in what was then Prussian Silesia. His father was a chaplain in the Prussian army. Friedrich first went to a Moravian school. The Moravians had a strong focus on personal religious experience, called Pietism.

However, Schleiermacher began to have doubts about these teachings. His father eventually allowed him to attend the University of Halle. This university was more open to new ideas, including rationalism, which emphasized reason and logic.

As a student, Schleiermacher read widely on his own. He learned about historical criticism of the New Testament, which involves looking at the Bible's history. He also developed a love for the philosophy of Plato and Aristotle. He studied the works of Immanuel Kant, a very influential philosopher. Schleiermacher started to combine ideas from Greek philosophers with Kant's thinking. During this time, he became quite skeptical and moved away from traditional Christian beliefs.

Becoming a Tutor and Chaplain

After finishing his studies, Schleiermacher worked as a private tutor for a noble family. This experience helped him appreciate family and social life. In 1796, he became a chaplain at the Charité Hospital in Berlin.

In Berlin, he spent time with educated people and studied philosophy deeply. He was greatly influenced by German Romanticism, a movement that valued emotion and imagination. He also studied the ideas of Baruch Spinoza and Plato.

During this time, he wrote an important book called Reden über die Religion (On Religion: Speeches to Its Cultured Despisers). In this book, he argued that religion has a special place in human nature. He also wrote Monologen (Soliloquies), where he shared his ideas about freedom and the human spirit. These works laid the foundation for his later ideas about religion and philosophy.

Serving as a Pastor

From 1802 to 1804, Schleiermacher worked as a pastor in the town of Stolp. He also continued his philosophical work. He wrote Grundlinien einer Kritik der bisherigen Sittenlehre (Outlines of a Critique of the Doctrines of Morality to date). This book criticized earlier moral systems, including those of Kant. He argued that a good moral system should look at all parts of human life and have one main principle.

University Professor in Berlin

In 1804, Schleiermacher became a professor of theology at the University of Halle. He quickly became well-known as a professor and preacher. During this period, he started his lectures on hermeneutics, the art of understanding texts.

After the Battle of Jena, he moved back to Berlin in 1807. He became a pastor at the Trinity Church. In 1809, he married Henriette von Willich.

When the University of Berlin was founded in 1810, Schleiermacher played a big part in its creation. He became a theology professor there and also secretary of the Prussian Academy of Sciences. He helped reorganize the Prussian church and strongly supported uniting the Lutheran and Reformed branches of German Protestantism. This led to the Prussian Union of Churches in 1817.

Schleiermacher taught many subjects at the university. These included New Testament studies, ethics, dogmatic and practical theology, church history, philosophy, psychology, dialectics (logic and metaphysics), politics, and aesthetics.

He also wrote his most important theological work, Der christliche Glaube (The Christian Faith). In this book, he argued that the basis of religious belief is a deep feeling of absolute dependence on God. This feeling is communicated through Jesus and the church. He wanted to reform Protestant theology and free religion from constantly changing philosophical ideas.

Schleiermacher supported liberty and progress in politics. After Napoleon's defeat, he was even accused by the Prussian government of "demagogic agitation." He felt isolated at times, but his church and lectures were always full.

He continued his translation of Plato and worked on a new edition of The Christian Faith. Sadly, in 1829, he lost his only son, Nathaniel. He said this loss "drove the nails into his own coffin."

Death and Legacy

Friedrich Schleiermacher died from pneumonia on 12 February 1834, at the age of 65.

His ideas had a lasting impact. For example, the asteroid 12694 Schleiermacher is named after him. A street in Berlin-Kreuzberg, Schleiermacherstrasse, was also named in his honor in 1875.

Schleiermacher's Key Ideas

Understanding Knowledge

Schleiermacher believed that humans have both a mind (ego) and a body (non-ego). He saw human life as these two parts working together. He thought that our senses and our intellect are always connected. There is no such thing as a "pure mind" or "pure body."

He said that our mind's main job is thinking. This thinking can be about receiving information or actively creating something. Both involve our senses and our intellect working together.

He also talked about "self-consciousness," which is being aware of ourselves. This self-consciousness is always both about us and about the world around us. When the world affects us, we feel pleasure or pain. He believed that religious feeling is the highest form of thought. In this feeling, we realize our connection with the world and with God. It is a feeling of being completely dependent on God.

Schleiermacher agreed with Immanuel Kant that our knowledge is limited by our experiences. However, he tried to show that we can still understand the true nature of things. He believed that all knowledge comes in the form of concepts (ideas) or judgments (statements). Concepts combine different parts of being into a single idea. Judgments connect concepts to specific objects.

He thought that our ability to form similar judgments and concepts comes from the fact that our minds and senses are similar to the way things exist in the world. This means that our knowledge can truly reflect reality.

The Art of Understanding (Hermeneutics)

Schleiermacher gave many lectures on hermeneutics, which is the study of how we understand texts. He wanted to change hermeneutics from just being about specific types of texts (like the Bible) to being about how people understand any text. He called this "the art of understanding."

He believed that a text is how an author shares their thoughts. These "inner thoughts" become "outer expression" through language. To understand a text, you need to think about both the author's inner thoughts and the language they used. This involves two parts:

- Grammatical interpretation: This deals with the language itself.

- Psychological (or technical) interpretation: This deals with the author's thoughts and goals.

The goal of hermeneutics for Schleiermacher was to understand the author's thoughts as deeply as possible. This is a historical process, meaning you learn about the time and place the author wrote. It's also a psychological process, using your intuition and connection with the author. Since both the reader and author are human, they share some common understanding, which makes it possible to understand each other.

Schleiermacher also talked about avoiding misunderstanding. He identified two types:

- Qualitative misunderstanding: Not understanding the words or language correctly.

- Quantitative misunderstanding: Missing the deeper meaning or nuance of the author's thoughts.

He even suggested that an interpreter might sometimes understand the author's thoughts better than the author did! This happens by figuring out why a work was created and finding connections with other works by the same author or in the same style.

While he believed in deep understanding, Schleiermacher admitted that "good interpretation can only be approximated." Hermeneutics is not a "perfect art." However, it helps the interpreter by "putting oneself in possession of all the conditions of understanding."

Schleiermacher's work had a huge impact on hermeneutics. He is often called "the father of modern hermeneutics as a general study." Later philosophers, like Martin Heidegger and Hans-Georg Gadamer, expanded hermeneutics even further. They applied it not just to texts but to understanding all human experiences.

Ideas on Ethics

Besides religion and theology, Schleiermacher also focused on the moral world. He believed that previous moral systems, including those of Immanuel Kant and Johann Gottlieb Fichte, had problems. He thought they lacked a clear basis, were incomplete, and didn't organize their ideas well.

Schleiermacher's own moral system tried to fix these issues. He defined ethics as the study of how human reason affects the world. He saw it as a descriptive science, like physical science, but focused on human actions.

He believed that the goal of ethics is for nature (everything that is not mind, including our bodies) to become a perfect symbol and tool of the mind. He thought that our conscience helps us know what is right. He didn't see moral laws as strict "commands" but as descriptions of how the mind, as conscious will, is above nature.

Schleiermacher brought back the idea of the summum bonum, or the highest good. This was the ideal goal for all human life. His system looked at how individuals act in relation to society and the universe.

He divided ethics into three parts:

- Doctrine of moral ends: What goals should moral actions achieve?

- Doctrine of virtue: The moral power within each person.

- Doctrine of duties: How to achieve ethical goals.

He believed that moral actions cannot be done alone. They happen within families, states, schools, churches, and society. He also thought that eternal hell was not compatible with God's love. He believed that divine punishment was meant to help people improve, not just to punish them. He was one of the first major theologians to teach Christian Universalism, the idea that all people will eventually be saved.

Thoughts on Society

Schleiermacher's book On Religion: Speeches to its Cultured Despisers addressed a growing gap he saw between educated people and general society. He wrote this during the Age of Enlightenment, when new ideas were changing Western Europe. While art and science were thriving, theological discussions seemed to be shrinking.

In On Religion, Schleiermacher argued that critics often oversimplified religion. He said they wrongly believed that religion was based only on fear of God or hope for an afterlife. He wanted to show that religion was a deeper, more fundamental part of human experience.

Religious Beliefs

Schleiermacher was deeply influenced by thinkers like Gottfried Leibniz and the Romantic movement. He had a profound and mystical view of the human spirit. His religious ideas are best seen in The Christian Faith, a very influential book in Christian theology.

He saw each person as a unique part of a larger, universal reason. He believed that our self-awareness is the first connection between our individual life and the universe. Each person is a unique reflection of the universe, a "microcosmos."

He argued that while we cannot fully grasp the unity of thought and being through just thinking or acting, we can find it within ourselves. We find it in our immediate self-consciousness, or what he called "feeling." This "feeling" is a deep awareness where the difference between subject and object disappears. This feeling is the core of our being, and it is where religion truly lies.

Over time, Schleiermacher used different words to describe this religious feeling. In his early days, he called it an intuition of the universe or a consciousness of the unity of reason and nature. Later, he described it as the feeling of absolute dependence, or being aware of our relationship with God.

Works by Schleiermacher

Schleiermacher's works were first published in three main sections:

- Theological writings

- Sermons

- Philosophical and other writings

Some of his important works include:

- Brief Outline for the Study of Theology (1830)

- The Christian Faith in Outline (1830–1)

- Christmas Eve: A Dialogue on the Incarnation (1826)

- Dialectic, or, The Art of Doing Philosophy (1903)

- On Religion: Speeches to its Cultured Despisers (1799, 1806, 1831)

- Hermeneutics and Criticism and Other Writings (1838)

Images for kids

Error: no page names specified (help).

- Hermeneutic circle

See also

In Spanish: Friedrich Schleiermacher para niños

In Spanish: Friedrich Schleiermacher para niños

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |