Christopher Hitchens facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Christopher Hitchens

|

|

|---|---|

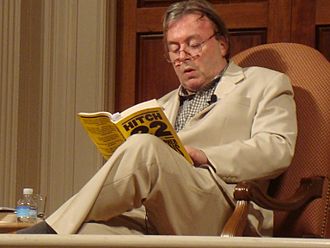

Hitchens in 2007

|

|

| Born |

Christopher Eric Hitchens

13 April 1949 Portsmouth, Hampshire, England

|

| Died | 15 December 2011 (aged 62) |

| Education | Balliol College, Oxford (BA) |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Era | Contemporary |

| School | New Atheism |

|

Notable ideas

|

Hitchens's razor |

|

Influences

|

|

|

Influenced

|

|

| Citizenship |

|

| Political party | Labour (1965–1967) International Socialists (1967–1971) |

| Signature | |

|

|

Christopher Eric Hitchens (born April 13, 1949 – died December 15, 2011) was a famous British-American writer and journalist. He wrote or edited more than 30 books about culture, politics, and literature. Hitchens was born and grew up in England. He worked as a journalist for the New Statesman magazine in London in the 1970s after studying at Oxford. In the early 1980s, he moved to the United States. There, he wrote for The Nation and Vanity Fair.

Hitchens's political ideas changed a lot during his life. At first, he called himself a democratic socialist. He was part of different socialist groups when he was young. He often criticized parts of American foreign policy. This included its involvement in wars and conflicts in Vietnam, Chile, and East Timor. However, he also supported the United States in the Kosovo War.

Hitchens believed the American Revolution and the U.S. Constitution were very important to his political beliefs. He supported gun rights and LGBT rights. After the 9/11 attacks, many people thought his politics moved more towards conservative ideas. But Hitchens did not like being called conservative. In the 2000s, he argued for the invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan. He also supported George W. Bush's re-election in 2004. He saw Islamism as the main threat to the Western World.

Hitchens described himself as an anti-theist. This means he believed all religions were false, harmful, and authoritarian. He strongly supported free speech, scientific discovery, and the separation of church and state. He argued that these ideas were better than religion for guiding human behavior. His famous saying, "What can be asserted without evidence can also be dismissed without evidence," is known as Hitchens's razor.

Hitchens passed away from problems related to esophageal cancer in December 2011. He was 62 years old.

Contents

Life and Career Highlights

Early Life and Education

Christopher Hitchens was born in Portsmouth, Hampshire, England. He was the older of two boys. His brother, Peter, also became a journalist. Their parents, Eric and Yvonne, met while serving in the Royal Navy during World War II. Christopher's mother was of Jewish background. He found this out when he was 38 years old.

Hitchens often called his father "the commander." His father served on HMS Jamaica, which helped sink a German battleship in 1943. Christopher praised his father's war efforts. He said it was "a better day's work than any I have ever done." His father's naval career meant the family moved often. They lived in places like Malta, where Peter was born.

Hitchens went to two private schools: Mount House School and Leys School. In 1967, he was accepted into Balliol College, Oxford. There, he studied Philosophy, Politics, and Economics. He finished his degree in 1970. As a teenager, he loved books by authors like Richard Llewellyn and George Orwell. In 1968, he appeared on the TV quiz show University Challenge.

In the 1960s, Hitchens joined the political left. He disagreed with the Vietnam War, nuclear weapons, and racism. He liked the protest movements of the 1960s and 1970s. He was inspired to become a journalist after reading an article by James Cameron.

Hitchens joined the Labour Party in 1965. But he was expelled in 1967 because he disagreed with Prime Minister Harold Wilson's support for the Vietnam War. He became interested in Trotskyism, which is a type of anti-Stalinist socialism. He then joined a small group that followed the ideas of Rosa Luxemburg.

Journalism in the UK (1971–1981)

Early in his career, Hitchens worked as a writer for International Socialism magazine. This magazine was published by a group called the International Socialists. They were a Trotskyist group that did not defend communist countries. Their motto was "Neither Washington nor Moscow but International Socialism."

In 1971, after traveling in the United States, Hitchens worked for the Times Higher Education Supplement. He was a social science writer. He was fired after six months. Next, he worked as a researcher for ITV's Weekend World.

In 1973, Hitchens started working for the New Statesman. His co-workers included famous writers like Martin Amis and Julian Barnes. Amis described him as "handsome, festive [and] gauntly left-wing." At the New Statesman, Hitchens became known as a left-wing writer. He worked as a war correspondent in places like Northern Ireland, Libya, and Iraq.

In November 1973, Hitchens reported from Greece about a political crisis. This became his first main article for the New Statesman. In 1977, he interviewed the Argentine dictator Jorge Rafael Videla. Hitchens later called this conversation "horrifying." He left the New Statesman for a short time to work for the Daily Express. He returned to the New Statesman in 1978 as an assistant editor and then foreign editor.

Writing in America (1981–2011)

Hitchens moved to the United States in 1981. He was part of an exchange program between the New Statesman and The Nation. After joining The Nation, he wrote strong criticisms of presidents Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush. He also criticized American foreign policy in South and Central America.

In 1992, Hitchens became a contributing editor for Vanity Fair. He wrote ten articles a year for them. He left The Nation in 2002 because he strongly disagreed with other writers about the Iraq War.

Some people think Hitchens was the inspiration for a character in the 1987 novel The Bonfire of the Vanities. In 1987, Hitchens's father died from esophageal cancer. This was the same disease that would later take Christopher's life. In April 2007, Hitchens became a U.S. citizen. He said he saw himself as both British and American.

He worked as a media fellow at the Hoover Institution starting in 2008. For Slate magazine, he often wrote under the column Fighting Words.

Hitchens spent part of his early career as a foreign correspondent in Cyprus. There, he met his first wife, Eleni Meleagrou. They had two children, Alexander and Sophia. His son, Alexander, born in 1984, later became a policy researcher. Hitchens continued to write essays from many different places, including Chad, Uganda, and Darfur in Sudan. In 1991, he won a Lannan Literary Award for Nonfiction.

Hitchens met Carol Blue in Los Angeles in 1989. They married in 1991. Hitchens said it was love at first sight. In 1999, Hitchens and Blue, who both criticized President Bill Clinton, gave a statement during Clinton's impeachment trial. This caused a public disagreement between Hitchens and his former friend, Sidney Blumenthal. The incident ended their friendship.

Before Hitchens's political views changed, the American writer Gore Vidal called Hitchens his "heir." In 2010, Hitchens criticized Vidal for believing in 9/11 conspiracy theories. Hitchens's strong support for the Iraq War helped him gain more readers. In 2005, he was named fifth on a list of "Top 100 Public Intellectuals."

Hitchens did not leave The Nation until after the September 11 attacks. He felt the magazine thought John Ashcroft was a bigger threat than Osama bin Laden. The 9/11 attacks made him feel "exhilarated." He saw it as a fight "between everything I love and everything I hate." This strengthened his belief in an active foreign policy against "fascism with an Islamic face." His many articles supporting the Iraq War led some to call him a neoconservative. However, Hitchens insisted he was not "a conservative of any kind." His friend Ian McEwan said he represented the anti-totalitarian left. In a 2010 BBC interview, Hitchens said he "still [thought] like a Marxist" and considered himself "a leftist."

In 2007, Hitchens wrote a controversial article called "Why Women Aren't Funny" for Vanity Fair. He argued that there was less social pressure for women to be funny. He also said that "women who do it play by men's rules." Vanity Fair published many letters disagreeing with his article. Hitchens later repeated his views in a video.

In 2007, Hitchens won the National Magazine Award for his columns in Vanity Fair. He was also a finalist in 2008 for his columns in Slate. His memoir Hitch-22 was nominated for an award in 2010. He won another National Magazine Award in 2011 for his columns about cancer. Hitchens also advised the Secular Coalition for America. In December 2011, before he died, Asteroid 57901 Hitchens was named after him.

Literature and Reviews

Hitchens wrote a monthly essay for The Atlantic and sometimes wrote for other literary magazines. His book Unacknowledged Legislation: Writers in the Public Sphere collected these works. In Why Orwell Matters, he argued that George Orwell's writings were still important today. The book Christopher Hitchens and His Critics: Terror, Iraq, and the Left includes many reviews of his essays and books.

In an interview, he named authors who influenced him. These included Aldous Huxley, George Orwell, and Evelyn Waugh. When asked about the difference between an autobiography and a memoir, he joked that most people's books should stay inside them.

University Teaching

Hitchens was a visiting professor at several universities:

- University of California, Berkeley

- The University of Pittsburgh

- The New School of Social Research

Relationship with His Brother

Christopher's younger brother was the journalist and author Peter Hitchens. Christopher said in 2005 that their main difference was their belief in God. Peter joined the International Socialists (a group Christopher introduced him to) from 1968 to 1975.

The brothers had a disagreement after Peter wrote an article in 2001. This article supposedly called Christopher a Stalinist. They later made up after Peter's third child was born. Peter's review of Christopher's book God Is Not Great led to another public argument, but they did not become estranged again.

In 2007, the brothers appeared together on BBC TV's Question Time. They disagreed on many topics. In 2008, in the U.S., they debated the 2003 invasion of Iraq and the existence of God. In 2010, they debated the role of God in civilization. At Christopher's memorial service, Peter read a passage from the Bible that Christopher had read at their father's funeral.

Political Views

In 2009, Forbes magazine listed Hitchens as one of the "25 most influential liberals in the U.S. media." The article noted that he would likely be surprised to be on this list. Hitchens's political ideas are also seen in his many writings and discussions. He once said about Ayn Rand's Objectivism, "I have always found it quaint, and rather touching, that there is a movement in the US that thinks Americans are not yet selfish enough."

Hitchens had mixed feelings about the idea of a Jewish homeland. He said, "I am an Anti-Zionist. I'm one of those people of Jewish descent who believes that Zionism would be a mistake even if there were no Palestinians."

Hitchens had long called himself a socialist and a Marxist. He began to move away from the traditional political left after what he called the "tepid reaction" of the Western left to the controversy over The Satanic Verses. He also disagreed with the left's support for Bill Clinton and their opposition to NATO intervention in Bosnia and Herzegovina in the 1990s. He later became a "liberal hawk" and supported the War on Terror. However, he had some concerns, like calling waterboarding torture after he experienced it himself.

Hitchens strongly criticized President Slobodan Milošević of Serbia and other Serbian politicians in the 1990s. He called Milošević a "fascist" and a "nazi" after the Bosnian genocide and ethnic cleansing in Kosovo. He was glad when Milošević died. Hitchens often accused the Serbian government of committing war crimes. He also criticized Croatian president Franjo Tuđman.

Hitchens supported gun rights and same-sex marriage.

Hitchens supported the European Union. In 1993, he said he liked the idea of European unity. He also criticized the "Eurosceptic movement" in the UK. He called them "fanatical" and "dogmatic."

Criticisms of Specific People

Hitchens wrote book-length essays about historical figures like Thomas Jefferson (Thomas Jefferson: Author of America), Thomas Paine (Thomas Paine's "Rights of Man": A Biography), and George Orwell (Why Orwell Matters).

He was also known for his strong criticisms of public figures of his time. These included Mother Teresa, Bill Clinton, and Henry Kissinger. He wrote full books about Clinton (No One Left to Lie To: The Triangulations of William Jefferson Clinton) and Kissinger (The Trial of Henry Kissinger). In 2007, while promoting his book God Is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything, Hitchens called the Christian evangelist Billy Graham "a self-conscious fraud" and "a disgustingly evil man."

In 1999, Hitchens wrote about Donald Trump for The Sunday Herald. Trump had shown interest in running for president in 2000. Hitchens described Trump as someone who "embodies his country" and "hates to be alone, who needs approval and reinforcement, who talks a better game than he plays, who is crude, hyperactive, emotional and optimistic." Hitchens had also written that Trump showed how "nobody is more covetous and greedy than those who have far too much."

Views on Religion

Hitchens was an antitheist. He said an antitheist is someone who is "relieved that there's no evidence" for God. He often spoke against the Abrahamic religions. When asked what he considered the "axis of evil," Hitchens replied, "Christianity, Judaism, Islam – the three leading monotheisms." In debates, Hitchens often posed "Hitchens's Challenge." He would ask people to name a moral action that a non-believer could not do. He also asked for an immoral action that only a person with faith could do.

In his best-selling book God Is Not Great, Hitchens criticized all religions. This included religions rarely criticized by Western non-believers, like Buddhism. Hitchens said that organized religion is "the main source of hatred in the world." He called it "violent, irrational, intolerant, allied to racism, tribalism, and bigotry, invested in ignorance and hostile to free inquiry, contemptuous of women and coercive toward children." He believed humanity needed a new Enlightenment. The book received mixed reviews. Some praised its "logical flourishes," while others called it "intellectual and moral shabbiness." God Is Not Great was nominated for a National Book Award in 2007.

God Is Not Great confirmed Hitchens's place in the "New Atheism" movement. He was made an Honorary Associate of the Rationalist International and the National Secular Society. He also joined the advisory board of the Secular Coalition for America. Hitchens said he would debate any religious leader who invited him. In 2007, Richard Dawkins, Hitchens, Sam Harris, and Daniel Dennett met for a private discussion called "The Four Horsemen."

That year, Hitchens began a series of written debates with Christian theologian Douglas Wilson. These debates were about the question "Is Christianity Good for the World?" They were published in Christianity Today magazine. This exchange became a book with the same title in 2008. A film called Collision: Is Christianity GOOD for the World? was made about their debates. On April 4, 2009, Hitchens debated William Lane Craig on the existence of God. On October 19, 2009, he debated whether the Catholic Church was a force for good. On November 26, 2010, Hitchens debated former British Prime Minister Tony Blair about religion.

In these debates, Hitchens was known for his strong and exciting public speaking. People described his speeches as having "wit and eloquence" and "verbal barbs." His supporters sometimes used the term "hitch-slap" for his clever remarks meant to challenge opponents.

Personal Life

Hitchens was raised Christian and went to Christian boarding schools. However, he chose not to take part in prayers from a young age. Later in life, he found out his mother's family had Jewish roots from Eastern Europe. Hitchens was married twice. First, to Eleni Meleagrou, a Greek Cypriot, in 1981. They had a son, Alexander, and a daughter, Sophia.

In 1991, Hitchens married his second wife, Carol Blue, an American screenwriter. They had a daughter named Antonia.

Hitchens saw reading, writing, and public speaking not just as a job, but as "what I am, who I am, [and] what I love."

In November 1973, Hitchens's mother passed away in Athens.

In 2007, after living in the U.S. for 25 years, he became an American citizen. He also kept his UK citizenship.

Illness and Death

On June 8, 2010, Hitchens was on a book tour in New York when he had a serious heart problem. Soon after, he announced he was postponing his tour to get treatment for oesophageal cancer.

In a Vanity Fair article called "Topic of Cancer," he wrote about his cancer treatment. He knew the long-term outlook was not good. He said he would be "a very lucky person to live another five years." Hitchens had been a heavy smoker and drinker since he was a teenager. He admitted these habits likely caused his illness. During his illness, Hitchens was treated by Francis Collins. He was part of Collins's new cancer treatment, which studies DNA to target damaged cells.

According to Christopher Buckley, Hitchens's former friend Sidney Blumenthal wrote him a letter before he died. Buckley said the letter offered "tenderness and comfort and implicit forgiveness."

Hitchens died from pneumonia on December 15, 2011, at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. He was 62. As he wished, his body was given to medical research. Mortality, a collection of his Vanity Fair essays about his illness, was published after his death in September 2012.

Reactions to His Death

Former British prime minister Tony Blair said, "Christopher Hitchens was a complete one-off, an amazing mixture of writer, journalist, polemicist and unique character. He was fearless in the pursuit of truth and any cause in which he believed."

Richard Dawkins said Hitchens was "a polymath, a wit, immensely knowledgeable, and a valiant fighter against all tyrants." Dawkins later called Hitchens "probably the best orator I've ever heard." He called his death "an enormous loss." American theoretical physicist Lawrence Krauss said, "Christopher was a beacon of knowledge and light in a world that constantly threatens to extinguish both." Bill Maher paid tribute to Hitchens on his show Real Time with Bill Maher. Salman Rushdie and English comedian Stephen Fry also paid tribute at a memorial event in 2012.

British Conservative and friend of Hitchens, Douglas Murray, wrote a tribute in The Spectator. He shared personal memories of Hitchens.

Three weeks before Hitchens died, George Eaton of the New Statesman wrote about him. He said Hitchens wanted to be remembered for his commitment to "reason, secularism, and pluralism." Eaton noted that Hitchens's illness came when he had a larger audience than ever. The Chronicle of Higher Education asked if Hitchens was the last public intellectual.

In 2015, an annual prize of $50,000 was created in his honor. It is for an author or journalist whose work shows a commitment to free expression, deep intellect, and a willingness to seek truth.

Books by Christopher Hitchens

- 1984 Cyprus. Later revised as Hostage to History: Cyprus from the Ottomans to Kissinger.

- 1987 Imperial Spoils: The Curious Case of the Elgin Marbles

- 1988 Blaming the Victims: Spurious Scholarship and the Palestinian Question (co-editor with Edward Said)

- 1988 Prepared for the Worst: Selected Essays and Minority Reports

- 1990 Blood, Class and Nostalgia: Anglo-American Ironies

- 1993 "For the Sake of Argument"

- 1997 The Parthenon Marbles: The Case for Reunification

- 1999 No One Left to Lie To: The Values of the Worst Family

- 2000 Unacknowledged Legislation: Writers in the Public Sphere

- 2001 The Trial of Henry Kissinger

- 2001 Letters to a Young Contrarian

- 2002 Why Orwell Matters (also known as Orwell's Victory)

- 2003 A Long Short War: The Postponed Liberation of Iraq

- 2004 Love, Poverty, and War: Journeys and Essays

- 2005 Thomas Jefferson: Author of America

- 2007 "Thomas Paine's Rights of Man: A Biography "

- 2007 God Is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything (published in the UK as God is not Great: The Case Against Religion)

- 2007 The Portable Atheist: Essential Readings for the Non-Believer (Editor)

- 2008 Christopher Hitchens and His Critics: Terror, Iraq and the Left (with Simon Cottee and Thomas Cushman)

- 2008 Is Christianity Good for the World? – A Debate (co-author, with Douglas Wilson)

- 2010 Hitch-22: A Memoir

- 2011 Arguably: Essays by Christopher Hitchens (UK edition as Arguably: Selected Prose)

- 2012 Mortality

- 2015 And Yet...: Essays

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Christopher Hitchens para niños

In Spanish: Christopher Hitchens para niños