Daniel Dennett facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Daniel Dennett

|

|

|---|---|

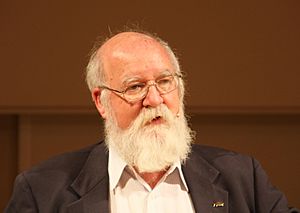

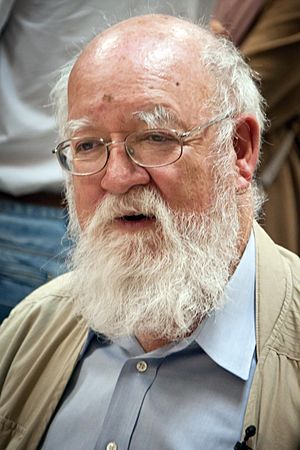

Dennett in Moscow in 2012

|

|

| Born |

Daniel Clement Dennett III

March 28, 1942 Boston, Massachusetts, U.S.

|

| Died | April 19, 2024 (aged 82) |

| Education | |

|

Notable work

|

|

| Spouse(s) |

Susan Bell

(m. 1962) |

| Awards |

|

| Era | 20th/21st-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School |

|

| Institutions | Tufts University |

| Thesis | The Mind and the Brain (1965) |

| Doctoral advisor | Gilbert Ryle |

|

Main interests

|

|

|

Notable ideas

|

Heterophenomenology Intentional stance Intuition pump Multiple drafts model Greedy reductionism Cartesian theater Belief in belief Free-floating rationale Top-down vs bottom-up design Cassette theory of dreams Alternative neurosurgery Sphexishness Brainstorm machine Deepity |

|

Influences

|

|

|

Influenced

|

|

| Signature | |

|

|

Daniel Clement Dennett III (born March 28, 1942 – died April 19, 2024) was an American thinker, writer, and cognitive scientist. He studied how our minds work, how science helps us understand the world, and how living things change over time through evolutionary biology.

He was a professor of philosophy at Tufts University in Massachusetts. Dennett was also known as one of the "Four Horsemen of New Atheism" because he openly shared his views on atheism and secularism. The other "Horsemen" were Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris, and Christopher Hitchens.

Contents

About Daniel Dennett

Daniel Clement Dennett III was born in Boston, Massachusetts, on March 28, 1942. His father worked for the American Embassy in Beirut, Lebanon, during World War II. Sadly, his father died in a plane crash when Daniel was young. His mother then brought him back to Massachusetts.

Daniel first became interested in philosophy at age 11 during summer camp. A counselor told him, "You know what you are, Daniel? You're a philosopher."

He went to Harvard University for his first degree in philosophy. Later, he earned his PhD from the University of Oxford in England. He studied with famous philosophers like W. V. Quine and Gilbert Ryle.

Dennett taught at the University of California, Irvine, before moving to Tufts University. He stayed there for many years. He often said he learned a lot from talking to leading scientists.

He received many awards for his work. These included the Jean Nicod Prize and the Erasmus Prize. The Erasmus Prize recognized his skill in explaining science and technology to many people.

Daniel Dennett passed away in April 2024 at the age of 82.

Daniel Dennett's Ideas

What is Free Will?

Daniel Dennett believed in something called "compatibilism" when it came to free will. This idea suggests that we can have free will even if everything is caused by something else. He thought that our decisions happen in two steps.

First, our brains create many ideas or choices. These ideas might pop up randomly. Second, we then choose which of these ideas are important. We use our intelligence to pick the best ones.

Dennett believed this process makes us feel like we are truly making our own choices. It also allows us to learn from our mistakes. He said that even if we could have thought more, we decide when "that's enough." Then, we take responsibility for our actions.

How Does the Mind Work?

Dennett spent much of his career trying to explain how the mind works. He wanted to understand consciousness based on scientific research. He believed that our brains process information in many ways at once.

He called this the "multiple drafts model" of consciousness. It's like our brains are constantly editing a story. This story is our experience of the world. Information comes in, and our brain keeps changing and adding to it.

Dennett thought that consciousness is a physical process in the brain. He argued that some ideas, like "qualia" (the private feeling of something, like the redness of red), are confusing. He believed they don't help us understand how the mind works scientifically.

He also said that he was a "teleofunctionalist." This means he thought we could understand the mind by looking at what it does. He also believed in "verificationism," which means ideas must be testable or provable.

Evolution and Life

Dennett believed that evolution by natural selection is a powerful way to explain how life developed. He saw evolution as an algorithm—a set of steps that leads to a result. He thought that even simple algorithms can involve some randomness.

He strongly supported the idea that many features of living things are "adaptations." This means they developed because they helped survival. He agreed with biologist Richard Dawkins on this point.

Dennett also wrote about how evolution might explain where our sense of morality comes from. He believed that our ability to be moral could have evolved naturally.

Views on Religion and Morality

Dennett was a well-known atheist and supporter of secularism. He was part of the Brights movement, which encourages a naturalistic worldview.

In his book Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon, he explored why people believe in religion. He looked at religious belief as a natural human behavior that could have evolutionary reasons.

He also studied religious leaders who secretly did not believe in God. He found that many felt alone but continued their work. They often felt they were still helping people by providing comfort and traditions. He wrote a book about this research called Caught in the Pulpit.

Memes and Deepities

Dennett was interested in the idea of "memetics." A meme is like an idea, behavior, or style that spreads from person to person within a culture. He thought it was a useful tool for understanding how ideas spread.

He was also critical of postmodernism. This is a way of thinking that suggests there are no absolute truths, only different interpretations. Dennett believed this view could make people distrust evidence and truth.

He also used the term "deepity." A deepity is a statement that sounds very wise and important but is actually either obvious or meaningless. For example, "Beauty is only skin deep!" is a deepity. It's true but simple, and it doesn't really tell you anything profound.

Artificial Intelligence (AI)

Dennett thought that artificial intelligence (AI) could make our lives more efficient. For example, AI helps doctors or GPS systems guide us. However, he also warned about the dangers of AI.

He worried that people might think AI systems are smarter than they really are. He believed that AI systems are often "parasitic." This means they rely on human intelligence rather than having their own deep understanding.

Dennett felt that creating AI with human-like understanding would be extremely difficult. He thought that super-intelligent AI was a very distant possibility. He believed other world problems were much more important to focus on.

Realism and How We See the World

Dennett had a balanced view on realism. He believed that things described by science, like electrons, really exist. They exist whether we perceive them or not. This is called scientific realism.

However, he also thought that some ideas are more like useful tools for understanding. For example, he saw beliefs as "logical constructs." They help us make sense of the world, even if they aren't physical things.

Dennett believed that how we talk about reality is shaped by our minds and language. This means our understanding of the world is not always a simple, direct copy of what's out there.

Personal Life

Daniel Dennett was married to Susan Bell in 1962. They lived in North Andover, Massachusetts. They had two children and five grandchildren. He also enjoyed sailing.

See also

In Spanish: Daniel Dennett para niños

In Spanish: Daniel Dennett para niños

- The Atheism Tapes

- Cartesian materialism

- Cognitive biology

- Mike Cooley (engineer)

- Evolutionary psychology of religion

- Jean Nicod Prize

Selected Works

- Brainstorms: Philosophical Essays on Mind and Psychology (1981)

- Elbow Room: The Varieties of Free Will Worth Wanting (1984) – about free will

- Content and Consciousness (1986)

- Consciousness Explained (1991)

- Darwin's Dangerous Idea: Evolution and the Meanings of Life (1995)

- Kinds of Minds: Towards an Understanding of Consciousness (1997)

- Brainchildren: Essays on Designing Minds (1998) – a collection of essays

- Freedom Evolves (2003)

- Sweet Dreams: Philosophical Obstacles to a Science of Consciousness (2005)

- Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon (2006)

- Neuroscience and Philosophy: Brain, Mind, and Language (2007) – co-authored

- Science and Religion: Are They Compatible? (2010) – co-authored

- Intuition Pumps And Other Tools for Thinking (2013)

- Caught in the Pulpit: Leaving Belief Behind (2013) – co-authored with Linda LaScola

- Inside Jokes: Using Humor to Reverse-Engineer the Mind (2011) – co-authored

- From Bacteria to Bach and Back: The Evolution of Minds (2017)

- I’ve Been Thinking (2023)

Images for kids