Franjo Tuđman facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Vrhovnik

Dr. Franjo Tuđman

|

|

|---|---|

Tuđman in 1995

|

|

| 1st President of Croatia | |

| In office 22 December 1990 – 10 December 1999 |

|

| Prime Minister |

|

| Preceded by | Himself (as President of the Presidency of the Republic of Croatia) |

| Succeeded by |

|

| President of the Presidency of the Republic of Croatia | |

| In office 25 July 1990 – 22 December 1990 |

|

| Prime Minister | |

| Deputy | Josip Manolić |

| Preceded by | Himself (as President of the Presidency of the Socialist Republic of Croatia) |

| Succeeded by | Himself (as President of Croatia) |

| President of the Presidency of the Socialist Republic of Croatia | |

| In office 30 May 1990 – 25 July 1990 |

|

| Prime Minister | Stjepan Mesić (as President of the Executive Council of the Socialist Republic of Croatia) |

| Deputy | Josip Manolić |

| Preceded by | Ivo Latin |

| Succeeded by | Himself (as President of the Presidency of the Republic of Croatia) |

| President of the Croatian Democratic Union | |

| In office 17 June 1989 – 10 December 1999 |

|

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by |

|

| Personal details | |

| Born | 14 May 1922 Veliko Trgovišće, Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes |

| Died | 10 December 1999 (aged 77) Zagreb, Croatia |

| Resting place | Mirogoj Cemetery, Zagreb, Croatia |

| Nationality | Croatian |

| Political party | SKH (1942–1967) HDZ (1989–1999) |

| Spouse |

Ankica Žumbar

(m. 1945) |

| Children | 3, including Miroslav |

| Parents |

|

| Alma mater |

|

| Profession | Politician, historian, soldier |

| Signature | |

| Nickname | "Francek" |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | Yugoslav Partisans (1942–45) Yugoslav People's Army (1945–61) Armed Forces of Croatia (1995–99) |

| Years of service | 1942–1961 1995–1999 |

| Rank | Major general (YPA) Vrhovnik (HV) |

| Unit | 10th Zagreb Corps |

| Battles/wars | World War II in Yugoslavia Croatian War of Independence Bosnian War |

Franjo Tuđman (born 14 May 1922 – died 10 December 1999) was a Croatian politician and historian. He became the first President of Croatia after the country gained independence from Yugoslavia. He served as president from 1990 until his death in 1999. Before that, he was the last President of the Presidency of SR Croatia from May to July 1990.

Tuđman was born in Veliko Trgovišće. As a young man, he fought in World War II as a member of the Yugoslav Partisans. After the war, he worked for the Ministry of Defence. He became a major general in the Yugoslav Army in 1960.

After his military career, he studied geopolitics. In 1963, he became a professor at the Zagreb Faculty of Political Sciences. He earned a doctorate in history in 1965. He worked as a historian until he had disagreements with the government.

Tuđman was part of the Croatian Spring movement. This movement wanted reforms in the country. He was put in prison in 1972 for his activities. He lived quietly for several years. When communism ended, he started his political career. He founded the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ) in 1989.

The HDZ won the first Croatian parliamentary elections in 1990. Tuđman became the President of the Presidency of SR Croatia. As president, Tuđman introduced a new constitution. He pushed for Croatia to become an independent country.

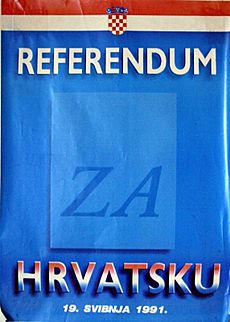

On 19 May 1991, people voted in an independence referendum. About 93 percent of voters approved it. Croatia declared independence from Yugoslavia on 25 June 1991. Some areas with a Serb majority started a revolt. They were supported by the Yugoslav Army. Tuđman led Croatia during its War of Independence.

A ceasefire was signed in 1992. But the war spread into Bosnia and Herzegovina. There, Croats first fought with Bosniaks. Their cooperation ended in late 1992. Tuđman's government supported Herzeg-Bosnia during the Croat-Bosniak War. This brought criticism from other countries.

In March 1994, he signed the Washington Agreement. He signed it with Bosnian President Alija Izetbegović. This agreement brought Croats and Bosniaks back together. In August 1995, he approved a big military action called Operation Storm. This operation effectively ended the war in Croatia.

In the same year, he signed the Dayton Agreement. This agreement ended the Bosnian War. He was re-elected president in 1992 and 1997. He stayed in power until he died in 1999. Many people praise his role in Croatia gaining independence. However, some critics have called his presidency authoritarian. After his death, surveys have shown that many Croatian people still have a positive view of him.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Franjo Tuđman was born on 14 May 1922. This was in Veliko Trgovišće, a village in northern Croatia. At that time, it was part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. His family moved to the house known as his birthplace soon after he was born.

His father, Stjepan, ran a local tavern. He was also active in politics. He was a member of the Croatian Peasant Party (HSS). Stjepan Tuđman was the president of the HSS committee in Veliko Trgovišće for 16 years. He was also elected mayor of Veliko Trgovišće in 1936 and 1938.

Franjo had an elder sister who died as a baby. He also had two younger brothers, Ivica and Stjepan. When Franjo was seven, his mother, Justina, died. She died while giving birth to her fifth child. Franjo attended elementary school in his village from 1929 to 1933. He was an excellent student.

He went to secondary school for eight years, starting in 1935. When he was 15, his father took him to Zagreb. There, he met Vladko Maček, the leader of the Croatian Peasant Party. Young Franjo first liked the HSS. But later, he became interested in communism. In 1940, he was arrested during student protests. These protests celebrated the anniversary of the Soviet October Revolution.

World War II

On 10 April 1941, the Independent State of Croatia (NDH) was declared. This was a state supported by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. Tuđman left school and started publishing secret newspapers.

He joined the Yugoslav Partisans in early 1942. His father also joined the Partisans. He became a founder of the State Anti-Fascist Council for the National Liberation of Croatia (ZAVNOH). Tuđman said that his father was arrested by the Ustaše, who governed the NDH. One of his brothers was taken to a concentration camp. Both survived. However, his youngest brother, Stjepan, was killed by the Gestapo while fighting for the Partisans in 1943.

Tuđman traveled between Zagreb and Zagorje. He used fake documents that said he was part of the Croatian Home Guard. He helped to start a partisan division in Zagorje. In May 1942, he was arrested by the Ustashas. But he managed to escape from the police station.

Military Career

Franjo Tuđman and Ankica Žumbar got married on 25 May 1945. They married in Belgrade. This showed their support for the Communist movement. On 26 April 1946, his father Stjepan and stepmother were found dead. The police said his father killed his wife and then himself. Other ideas suggest Ustasha guerrillas or the Yugoslav secret police were involved.

Franjo and Ankica finished their secondary school education after the war. In 1953, Tuđman became a colonel. In 1959, he was promoted to major general. At 38, he was the youngest general in the Yugoslav Army. This was unusual for a Croat at that time.

In 1954, he became secretary of JSD Partizan Belgrade. In 1958, he became its president. He was the first colonel to hold this position. He was put there to fix problems in the club, especially the football section. During his time, the club adopted the black-white striped uniform. This uniform is still used today.

Tuđman went to the military academy in Belgrade. He graduated from the tactical school in 1957. He was an excellent student. Before he turned 40, he became the youngest general in the Yugoslav Army. He was very involved in communist training while in Belgrade. His three children were born there.

Institute Work

In 1963, he became a professor at the University of Zagreb Faculty of Political Sciences. He taught a course on "Socialist Revolution and Contemporary National History". He left active army service in 1961. He then started working at the Institute for the History of Workers' Movement of Croatia. He was its director until 1967.

Tuđman started to focus more on a Croatian view of history. This caused some professors to disagree with him. In 1964, one professor called him a nationalist. Under Tuđman's leadership, the Institute offered new ways to understand Yugoslav history. This led to conflicts with the official history.

He did not have a formal history degree. So, he decided to get a doctorate to keep his job. His thesis was about why the Yugoslav Monarchy broke down. The University of Zagreb first rejected his thesis. But the Faculty of Arts in Zadar accepted it. He graduated on 28 December 1965.

In his thesis, he said the main reason for Yugoslavia's breakdown was its harsh and corrupt government. This was different from the common view at the time. He publicly supported the goals of the Declaration on the Name and Status of the Croatian Literary Language. However, the Croatian Parliament and the League of Communists of Croatia criticized this. The institute asked Tuđman to resign.

In 1966, he was accused of copying parts of his doctoral thesis. He was then removed from the Institute. He was forced to retire in 1967. Between 1962 and 1967, he was also involved in the Croatian League of Communists. He was a deputy in the Croatian Parliament from 1965 to 1969.

Political Activism

Tuđman wrote many articles criticizing the Yugoslav government. His most important book from that time was Velike ideje i mali narodi ("Great ideas and small nations"). This book discussed political history. It caused him to disagree with the main ideas of the Yugoslav Communist leaders.

In 1970, he joined the Croatian Writers' Society. In 1972, he was sentenced to two years in prison. This was for "subversive activities" during the Croatian Spring. This movement wanted more freedom for Croatia within Yugoslavia. Yugoslav President Josip Broz Tito reportedly helped him get a shorter sentence. Tuđman was released after nine months in prison.

In 1977, he traveled to Sweden using a fake passport. He met with Croatians living abroad. He gave an interview to Swedish TV about the situation of Croats in Yugoslavia. When he returned, he was put on trial again in 1981. He was accused of spreading "enemy propaganda." He was found guilty and sentenced to three years in prison. But he served only eleven months.

In June 1987, he became a member of the Croatian PEN centre. On 6 June 1987, he traveled to Canada with his wife. He met many Croatian Canadians. These meetings with Croatians living abroad later led to many rumors.

Forming a National Plan

In the late 1980s, Yugoslavia was starting to fall apart. Different national groups had strong disagreements. Tuđman created a plan for Croatia. His main goal was to create an independent Croatian nation-state. He believed all past disagreements should be put aside. This meant getting strong support, especially financial, from Croatians living outside the country.

Even though he wanted an independent Croatia, he knew it would be hard. His first idea was not a fully independent Croatia. Instead, he suggested a Yugoslavia where each part had more freedom and democracy. Tuđman saw Croatia's future as a country with a strong economy. He believed it would move closer to central Europe and away from the Balkans.

Regarding national conflicts, he thought that Serbian nationalism, supported by the Yugoslav Army, could cause problems in Croatia and Bosnia. He suggested that Serbs in Croatia, who made up 12% of the population, should have cultural freedom. They would also have some local self-rule.

For Bosnia and Herzegovina, Tuđman was less clear. He did not see Bosnia as a separate country. He said it was part of Croatia before the Ottoman invasion.

On 17 June 1989, Tuđman founded the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ). This was a Croatian nationalist movement. It focused on Croatian values, Catholicism, and historical traditions. These traditions had been suppressed in communist Yugoslavia. The goal was to gain national independence and create a Croatian nation-state.

1990 Election Campaign

Tensions within the Communist party of Yugoslavia led to free elections in spring 1990. These were the first free elections for the Croatian Parliament since 1913. The HDZ held its first meeting in February 1990. Tuđman was elected its president. The election campaign lasted from late March to April 1990. Tuđman got support from Croatians living abroad, like Gojko Šušak.

Tuđman focused his campaign on the idea of Croatian nationhood. He said that money earned in Croatia should stay in Croatia. He also wanted to stop giving money to less developed parts of Yugoslavia or the army. He talked about the economic problems. He called for a market economy and a democracy. He supported joining the European Community. He believed Yugoslavia could only survive as a loose union of states.

His main opponent was Ivica Račan from the League of Communists of Croatia (SKH). Tuđman's ideas about Croatia's past and independence were not popular among Croatian Serbs. Serbian media criticized the HDZ. They said a HDZ victory would bring back the bad times of the NDH. A few weeks before the elections, the army removed weapons from defense stores across Croatia.

The elections were for all 356 seats in the parliament. Tuđman's party won a clear majority. They got about 60% of the votes, or 205 seats. Tuđman was elected President of Croatia on 30 May 1990. After the HDZ won, the nationalistic Serb Democratic Party (SDS) quickly gained power in areas with many Serbs.

President of Croatia (1990–1999)

After the election, the new government introduced the traditional Croatian flag and coat of arms. They removed Communist symbols. The word "Socialist" was taken out of the republic's name. New constitutional changes were proposed. These included many political, economic, and social changes.

Tuđman offered a vice-presidency to Jovan Rašković, the SDS president. But Rašković refused. He told his party's elected members to boycott the parliament. Local Serb police in Knin started acting independently. They often did not follow orders from Zagreb. Many government workers, especially in the police, lost their jobs. This was because the government wanted the number of people from different ethnic groups in public service to match their percentage in the population.

On 25 July 1990, a Serbian Assembly was formed in Srb, near Knin. Jovan Rašković announced a vote on "Serb sovereignty and autonomy" in Croatia in August 1990. Tuđman called this illegal. A series of events followed in Serb-populated areas around Knin. This was known as the Log Revolution. The revolt in Knin made the Croatian government realize it needed more weapons. The new Defence Minister, Martin Špegelj, bought weapons from Hungary. Croatia did not have a regular army. So, the government focused on building up the police force. By January 1991, there were 18,500 policemen. By April 1991, there were about 39,000. On 22 December 1990, the Croatian Parliament approved the new constitution. The Serbs in Knin declared the Serbian Autonomous Oblast of Krajina.

In December 1990, Tuđman and Slovenian President Milan Kučan suggested a new structure for Yugoslavia. They proposed a confederation. Tuđman believed a confederation of independent republics could help Croatia join the European Community faster. Leaders of the Yugoslav republics held many meetings in early 1991. They tried to solve the growing crisis. On 25 March 1991, Tuđman and Slobodan Milošević met at Karađorđevo. This meeting became controversial. Some claimed the two presidents discussed dividing Bosnia and Herzegovina between Serbia and Croatia. However, there is no proof of such an agreement.

War Years

On 1 March, the Pakrac clash happened. Local Serb police took over the town's police station. They declared Pakrac part of SAO Krajina. This was one of the first big clashes between Croat forces and the rebel SAO Krajina. It ended without deaths. Croatian control was restored. On 31 March, a Croatian police group was attacked at the Plitvice Lakes.

Until spring 1991, Tuđman and the Slovenian leaders were willing to accept a compromise. They wanted a confederation or alliance of independent states within Yugoslavia. But the Serbian leaders rejected their ideas. Armed attacks became more frequent. So, Tuđman decided to make Croatia fully independent. On 25 April 1991, the Croatian Parliament decided to hold an independence referendum on 19 May. Most Croatian Serbs did not vote. The turnout was 83.56%. Of those, 93.24% voted for Croatia's independence. Both Slovenia and Croatia declared independence from Yugoslavia on 25 June 1991. The Yugoslav side said they were breaking away illegally. The federal government ordered the JNA to take control of border crossings in Slovenia. This led to the Ten-Day War. The JNA was defeated. The war ended with the Brioni Agreement. A three-month pause was put on the independence decision.

The armed incidents of early 1991 grew into a full war by summer. Tuđman's first plan was to get support from the European Community. He wanted to avoid direct fighting with the JNA. He rejected the Defence Minister's idea for a big attack. He thought it would hurt Croatia's international standing. Also, he doubted the Croatian army was ready. The new Croatian Army had only four brigades in September 1991. As the war grew, Tuđman formed a government that included members from most parties.

Heavy fighting happened in Vukovar. About 1,800 Croat fighters stopped the JNA from moving into Slavonia. Vukovar became very important to both sides. Its strong defense against a much larger army was inspiring. People called it a "Croatian Stalingrad". More losses and public complaints made Tuđman act. He ordered the Croatian National Guard to surround JNA army bases. This started the Battle of the Barracks. Tuđman named Gojko Šušak the new Minister of Defence in September 1991.

In early October 1991, the JNA increased its attacks in Croatia. On 5 October, Tuđman gave a speech. He called on everyone to fight against "Greater Serbian imperialism." This was being carried out by the Serb-led JNA, Serbian paramilitary groups, and rebel Serb forces. Two days later, the Yugoslav Air Force bombed Banski Dvori. This was the seat of the Croatian Government in Zagreb. Tuđman was meeting with other leaders there, but no one was hurt. On 8 October, the Croatian Parliament broke all ties with Yugoslavia. It declared full independence.

In November 1991, the Battle of Vukovar ended. The city was destroyed. The JNA and Serbian groups took control of about a quarter of Croatia's land by the end of 1991. In December 1991, the SAO Krajina declared itself the Republic of Serbian Krajina (RSK). By the end of 1991, sixteen ceasefires were signed. None of them lasted longer than a day.

On 19 December 1991, Iceland and Germany recognized Croatia's independence. Many people believe Tuđman's good relationship with Germany's foreign minister helped this decision. Fighting in Croatia stopped for a while in January 1992. This was when the Vance plan was signed. Tuđman hoped that UN peacekeepers would secure Croatia's borders. But the military situation in Croatia remained uncertain.

Bosnian War

As the war in Croatia slowed down, the situation in Bosnia and Herzegovina got worse. The JNA used Bosnia to attack Croatia. But it avoided the Croat-majority part of Herzegovina. Tuđman doubted that Bosnia and Herzegovina could survive. But he supported its independence if it stayed out of a Yugoslav federation and Serbian influence. The first Croat deaths in Bosnia happened in October 1991. This was when the village of Ravno was attacked by the JNA.

The Bosniak leaders first wanted to stay in a smaller Yugoslavia. But they later changed their mind and chose independence. The Croat leaders started organizing themselves in Croat-majority areas. On 18 November 1991, they formed the Croatian Community of Herzeg-Bosnia. This was an independent Croat area. Tuđman discussed joining Herzeg-Bosnia to Croatia. He thought Bosnian leaders wanted to stay in Yugoslavia. However, in February 1992, he told Croats in Bosnia to support the upcoming Bosnian independence referendum. Izetbegović declared Bosnia's independence on 6 April. Croatia immediately recognized it.

At the start of the Bosnian war, Croats and Bosniaks formed an alliance. But it was often difficult. The Croatian government helped arm both Croat and Bosniak forces. On 21 July 1992, the Agreement on Friendship and Cooperation was signed. Tuđman and Izetbegović signed it. This agreement created military cooperation between the two armies. In September 1992, they signed two more agreements. These were about cooperation and future talks on how Bosnia and Herzegovina would be organized. But Izetbegović rejected a military pact. In January 1993, Tuđman said that Bosnia and Herzegovina could only survive as a union of three nations.

Over time, relations between Croats and Bosniaks got worse. This led to the Croat–Bosniak War. The Bosniak side claimed that Tuđman wanted to divide Bosnia and Herzegovina. This idea became more accepted by other countries. This made it hard for Tuđman to protect Croatia's interests and support Herzeg-Bosnia. As the conflict grew, Croatia's foreign policy faced problems.

Throughout 1993, several peace plans were suggested by other countries. Tuđman and the Herzeg-Bosnia leaders accepted all of them. This included the Vance-Owen Plan in January 1993. However, no lasting ceasefire was agreed upon. In early 1994, the United States became more involved in ending the wars. They were worried about how the Croat-Bosniak war helped the Serbs. They put pressure on both sides to sign a truce. The war ended in March 1994 with the signing of the Washington Agreement. In June 1994, Tuđman visited Sarajevo. He met with Alija Izetbegović. They talked about creating the Croat-Muslim Federation. They also discussed its possible union with Croatia.

Ceasefire in Croatia

Croatian diplomacy worked hard to get recognition from other countries. Croatia was recognized by the European Community on 15 January 1992. It became a member of the United Nations on 22 May. In April 1992, Washington recognized Croatia, Slovenia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina at the same time. In May 1992, Croatia started diplomatic relations with China. A year later, Tuđman was the first president from former Yugoslavia to visit China.

The war caused great damage. It also hurt tourism, trade, and investments. President Tuđman estimated the direct damage at over $20 billion. He said Croatia was spending $3 million daily to care for hundreds of thousands of refugees. When the ceasefire of January 1992 began, Croatia slowly started to recover. Economic activity grew. Talks with the leaders of RSK did not go anywhere. So, the Defence Minister, Gojko Šušak, started collecting weapons. This was to prepare for a military solution.

Tuđman won the presidential elections in August 1992. He got 57.8% of the votes in the first round. At the same time, parliamentary elections were held. These were also won by HDZ.

In January 1993, the Croatian Army launched Operation Maslenica. They recaptured the important Maslenica bridge. This bridge connected Dalmatia with northern Croatia. The UN Security Council criticized the operation. But there were no punishments. This victory helped Tuđman against those who said he was weak in dealing with RSK and the UN.

Despite clashes with RSK forces, the economy improved a lot in 1993 and 1994. Unemployment slowly went down. On 4 April 1993, Tuđman named Nikica Valentić as prime minister. Steps to control inflation in 1993 were successful. The Croatian dinar, a temporary currency, was replaced by the kuna in 1994. Economic growth reached 5.9% in 1994.

End of the War

In May 1995, the Croatian army launched Operation Flash. This was its third operation against RSK since the January 1992 ceasefire. They quickly recaptured western Slavonia. International diplomats created the Z-4 Plan. It suggested that RSK rejoin Croatia. RSK would keep its flag and have its own president, parliament, police, and currency. Tuđman was not happy with the plan. But RSK authorities rejected it completely.

On 22 July 1995, Tuđman and Izetbegović signed the Split Agreement. This agreement committed both sides to a "joint defense against Serb aggression." Tuđman soon acted on this. He started Operation Summer '95. This was carried out by joint forces of the Croatian Army (HV) and the Croatian Defence Council (HVO). These forces took over towns in western Bosnia. This almost cut off Knin from Republika Srpska and FR Yugoslavia.

At 5:00 a.m. on 4 August 1995, Tuđman publicly approved the attack on RSK. This was called Operation Storm. He called on the Serb army and their leaders in Knin to surrender. At the same time, he told Serb civilians to stay in their homes. He promised to protect their rights. The decision to go straight for Knin, the center of RSK, worked. By 10 a.m. on 5 August, Croatian forces entered the city with very few losses. By the morning of 8 August, the operation was mostly over. Croatia regained control of 10,400 square kilometers (4,000 square miles) of land. Around 150,000–200,000 Serbs left. Some crimes were committed against the civilians who stayed.

A joint attack by Croatian and Bosniak forces followed in western and northern Bosnia. Bosnian Serb forces quickly lost land. They were forced to negotiate. Talks for a peace treaty were held in Dayton, Ohio. Tuđman insisted on solving the issue of RSK-held eastern Slavonia. He wanted it to return peacefully to Croatia at the Dayton peace talks. On 1 November, he had a strong discussion with Milošević. Milošević said he did not control the region's leaders. Tuđman was ready to stop the Dayton agreement and continue the war if Slavonia was not peacefully reunited. The military situation gave him an advantage. Milošević agreed to his request.

The Dayton Agreement was written in November 1995. Tuđman was one of its signers. The leaders of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia also signed it. This agreement ended the Bosnian War. On 12 November, the Erdut Agreement was signed with local Serb authorities. This agreement was about the return of Eastern Slavonia, Baranja and Western Syrmia to Croatia. It included a two-year transition period. This ended the war in Croatia. Official numbers in 1996 showed that 180,000 homes were destroyed. Also, 25% of Croatia's economy was destroyed. The material damage was estimated at US$27 billion.

Post-War Policy

In 1995, parliamentary elections were held. HDZ won with 75 out of 127 seats. Tuđman named Zlatko Mateša as the 6th prime minister. He formed the first government of independent Croatia after the war. Elections were also held in Zagreb. Opposition parties won these local elections. Tuđman refused to formally approve the suggested Mayor of Zagreb. This led to the Zagreb crisis. In 1996, a big protest happened in Zagreb. This was because the broadcasting license for Radio 101, a station critical of the ruling party, was taken away.

Some international groups criticized how the media was treated. For example, the Feral Tribune, a Croatian newspaper, faced several lawsuits from government officials. Some opposition parties in Croatia believed Tuđman was making Croatia less European. They said he acted like a dictator. Other parties, like the Croatian Party of Rights, thought Tuđman was not strong enough in defending the Croatian state.

Croatia became a member of the Council of Europe on 6 November 1996. On 15 June 1997, Tuđman won the presidential elections. He got 61.4% of the votes. He was re-elected for a second five-year term. Marina Matulović-Dropulić became the Mayor of Zagreb after winning the 1997 local elections. This officially ended the Zagreb crisis.

In January 1998, Eastern Slavonia officially became part of Croatia again. In February 1998, Tuđman was re-elected as President of HDZ. The start of the year saw a large union protest in Zagreb. Because of this, the government passed laws about public gatherings in April. After the war, Tuđman suggested bringing the remains of those killed during the Yugoslav death march of Nazi collaborators to Jasenovac. He later dropped this idea. This idea included burying Ustaša troops, anti-fascist Partisans, and all civilians together. In 1998, Tuđman said his plan for national reconciliation prevented a civil war in Croatia.

Economy

After the war, Croatia's economy started to grow again. Reconstruction efforts helped this growth. People started spending more money and businesses invested. This improved economic conditions from 1995 to 1997. Real economic growth was 6.8% in 1995, 5.9% in 1996, and 6.6% in 1997.

In 1995, a Ministry of Privatization was created. Privatization in Croatia had just started when the war broke out in 1991. The war caused huge damage to infrastructure. This included the tourism industry, which brought in a lot of money. Because of this, changing from a market socialist economy to a free-market economy was slow. Public trust decreased when many state-owned companies were sold to people connected to politics for low prices. The ruling party was criticized for giving businesses to a small group of privileged owners.

The way privatization was done led to more state ownership. Unsold shares were given to state funds. In 1999, the private sector made up 60% of the economy. This was lower than in other former socialist countries. The sale of large government-owned companies mostly stopped during and right after the war. By the end of Tuđman's rule, about 70% of Croatia's major companies were still owned by the state. This included water, electricity, oil, transportation, telecommunications, and tourism.

Value-added tax was introduced in 1998. The government budget had a surplus that year. The consumer boom ended when the economy went into a recession in late 1998. This was due to a bank crisis where 14 banks went bankrupt. Economic growth slowed to 1.9%. The recession continued in 1999. Unemployment increased from about 10% in 1996 and 1997 to 11.4% in 1998. By the end of 1999, it reached 13.6%. The country came out of the recession in late 1999.

Foreign Policy

Mate Granić was the Minister of Foreign Affairs from 1993 until Tuđman's time ended. In 1996, he signed an agreement to normalize relations with FR Yugoslavia. On 9 September 1996, Croatia started diplomatic relations with FR Yugoslavia.

The US played a main role in reaching a peace treaty in the region. It continued to have the most influence after 1995. The Croatian attacks in 1995 did not get full support from the US. But the US supported Croatia's demands for its land. However, Croatian-American relations after the war were not as Tuđman expected. Serb minority rights and cooperation with the ICTY became main issues. This led to worse relations in late 1996 and 1997. Tuđman tried to reduce this pressure by having closer ties with Russia and China. In November 1996, he received the Medal of Zhukov from Russian President Boris Yeltsin. This medal was for his help in the fight against fascism.

A union between Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, agreed upon in the Washington Agreement, was not fully achieved. The Croat-Bosniak Federation existed mostly on paper. In August 1996, Tuđman and Izetbegović agreed to fully carry out the Dayton agreement. Herzeg-Bosnia was to be officially ended by the end of the month.

In 1999, NATO started its actions in Kosovo. Tuđman was worried about possible damage to Croatia's economy and tourism. This damage was estimated at $1 billion. Still, the government supported NATO. It allowed NATO planes to use Croatia's airspace. In May, Tuđman said a possible solution was to send UN peacekeepers to Kosovo. This would allow Albanian refugees to return. Yugoslav forces would then move to Serb-majority northern Kosovo.

Relation to the Catholic Church

Tuđman believed the Catholic religion was important for the modern Croatian nation. When he took his oath in 1992, he added the phrase "So help me God!" This was not part of the official text then. In 1997, he officially included this sentence in the oath. Tuđman's time as president saw a return of Catholic faith in Croatia. More people went to church. Even former communists took part in church ceremonies. The government helped fund the building and repair of churches and monasteries. Between 1996 and 1998, Croatia signed agreements with the Holy See. These agreements gave the Catholic Church in Croatia some financial rights.

Health Problems and Death

Tuđman was diagnosed with cancer in 1993. His health got worse by the late 1990s. On 1 November 1999, he appeared in public for the last time. While he was in the hospital, opposition parties said the ruling HDZ was hiding that Tuđman had already died. They claimed the authorities were keeping his death a secret to win more seats in the upcoming January 2000 general election. Tuđman's death was officially announced on 10 December 1999. He had a funeral Mass in Zagreb's Cathedral. He was buried in Mirogoj Cemetery.

Vrhovnik

The Croatian Parliament gave Tuđman the military rank of Supreme Commander of Croatia, or 'Vrhovnik', on 22 March 1995. This was the highest honorary title in the Croatian Armed Forces. It was similar to a Marshal. Tuđman was the only person to ever hold this rank. He held it until his death. The uniform for this position was reportedly based on the uniform of Josip Broz Tito. The title was eventually removed in 2002.

ICTY and Historical Views

The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) was set up by the United Nations in 1993. This court investigated serious crimes committed during the wars in former Yugoslavia. Croatia passed a law to cooperate with the ICTY. However, relations between the ICTY and Croatia became difficult after 1997. Tuđman criticized the ICTY's work in 1999. The ICTY's chief prosecutor, Louise Arbour, said she was not happy with Croatia's cooperation.

During Tuđman's life, the first ICTY chief prosecutors did not consider charging him. In 2002, a new ICTY prosecutor, Carla del Ponte, said she would have charged Tuđman if he had still been alive. A senior Tribunal prosecutor also said there would have been enough evidence to charge him.

In 2000, British Channel 4 television showed a report. It claimed to have recordings of Franjo Tuđman. In these, he supposedly talked about dividing Bosnia and Herzegovina with the Serbs after the Dayton Agreement. They said the then Croatian President Stjepan Mesić gave them access to 17,000 transcripts. Mesić and his office denied giving any transcripts. They called the report a "sensationalistic story that has nothing to do with the truth."

In a 2013 verdict about the trial of Prlić and others, the ICTY found that Tuđman, along with others, was part of a plan. This plan aimed to create a Croatian entity that would reunite the Croatian people. This was to be done through actions that affected Bosnian Muslims. However, the court did not find him guilty of any specific crimes. In 2016, the Appeals Chamber confirmed that the trial court "made no explicit findings concerning [Tudjman's, Šušak's and Bobetko's] participation in the JCE and did not find [them] guilty of any crimes."

Tuđman as Historian

Tuđman did not have a formal history degree. He looked at history as a scholar and a Croatian lawyer. He always saw history as a way to shape society. His long book, Hrvatska u monarhističkoj Jugoslaviji (Croatia in Monarchist Yugoslavia), is used as reading material at some Croatian universities. His shorter writings on national issues, like Nacionalno pitanje u suvremenoj Europi (The National question in contemporary Europe), are still seen as important essays. They discuss unresolved national and ethnic disputes and the creation of nation-states in Europe.

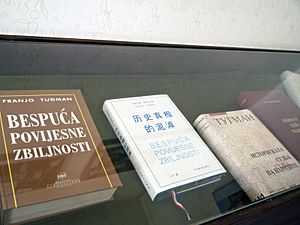

Horrors of War

In 1989, Tuđman published Bespuća povijesne zbiljnosti. This book was published in English in 1996 as Horrors of War: Historical Reality and Philosophy. The book questioned the number of victims killed during World War II in Yugoslavia. This was especially true for the Jasenovac concentration camp. Tuđman had done this before in a work published in 1982. The Yugoslav government's estimates put the number of Jasenovac victims between 600,000–700,000. Some Serbian historians even suggested up to one million victims. Tuđman felt that Jasenovac was being used to blame all Croats. He thought it was used to prove that Croatian nationalism was "genocidal."

The last serious research on victim numbers before the Yugoslav wars was done by Croatian economist Vladimir Žerjavić and Serbian researcher Bogoljub Kočović. Both found about 83,000 deaths in Jasenovac. They used different methods. In his book, Tuđman estimated that the total number of victims in the Jasenovac camp was between 30,000 and 40,000. He listed the victims as "Gypsies, Jews and Serbs, and even Croatians." He emphasized that the camp was organized as a "work camp." He estimated that a total of 50,000 were killed in all Ustaše camps throughout the NDH. While he correctly questioned the very high numbers, he gave figures that were too low.

In Horrors of War, Tuđman stated that 900,000 Jews died in the Holocaust instead of six million. Besides war statistics, Tuđman's book had views on the role of Jewish people in history. Many readers found these views too simple and biased. Some have called it anti-semitic. Tuđman based his views on the memories of a Croatian former Communist, Ante Ciliga. Ciliga described his experiences at Jasenovac. He claimed Jewish prisoners had a special position in Jasenovac. Tuđman added that most prisoners died at the hands of Jewish people, who controlled the killing process, not the Ustaše.

In 1994, Tuđman apologized for his remarks about Jewish people. He said that his views on Jewish people had changed since the book was published. The problematic parts were removed in the English version published in 1996. But they were kept in the Croatian, French, and German versions. On 22 April 1998, Tuđman welcomed the first Israeli ambassador to Croatia, Natan Meron.

Legacy

His supporters say Tuđman created the foundation for an independent Croatia. They also say he helped the country move away from communism. He is sometimes called the "father of the country." This is because of his role in Croatia gaining independence. His legacy is still strong in many parts of Croatia. It is also strong in parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina where Croatians are the majority. There are schools, squares, and streets named after him in some cities. Statues have also been built. In December 2006, a large square in Zagreb was named after him. In June 2015, the Minister of Maritime Affairs Transport and Infrastructure said the rebuilt Zagreb International Airport would be named after Tuđman.

Some observers criticized his time as president. They called it authoritarian. One historian said that Tuđman chose chauvinism instead of healthy nationalism. He also chose favoritism instead of a free market economy. He chose the idea of a strong state instead of freedom. He chose traditionalism instead of being modern and open to the world. This was a bad choice for a small country like Croatia that needs to be open to grow.

Public Opinion

Tuđman's approval ratings were mostly positive during his presidency. They were generally higher than the rest of the government. His approval increased a lot after Croatia joined the United Nations in May 1992. It also rose after successful military operations in January 1993 and August 1995. And it increased after eastern Slavonia was peacefully reunited in January 1998. Polls showed a drop in support in late 1993, throughout 1994, and in 1996. From early 1998, his approval slowly went down. But it increased slightly in November 1999.

In a December 2002 poll, 69% of voters had a positive opinion of Tuđman. In a June 2011 poll, 62% of voters gave Tuđman the most credit for creating independent Croatia. In December 2014, a survey of 600 people showed that 56% saw him as a positive figure. 27% said he had both positive and negative aspects. 14% saw him as a negative figure.

In a July 2015 survey about renaming Zagreb Airport after Tuđman, 65.5% supported the idea. 25.8% were against it. And 8.6% had no opinion.

| Date | Event | Approval (%) |

|---|---|---|

| December 1991 | 69 | |

| May 1992 | Croatia accepted into the UN | 77 |

| July 1992 | 71 | |

| January 1993 | Operation Maslenica | 76 |

| May 1993 | 61 | |

| December 1994 | 55 | |

| August 1995 | Operation Storm | 85 |

| October 1996 | 60 | |

| July 1997 | Re-elected president | 65 |

| February 1998 | 50 | |

| October 1998 | 44 | |

| November 1999 | 45 |

Immediate Family

- Widow: Ankica Tuđman (1926–2022)

- Sons: Miroslav Tuđman (1946–2021) and Stjepan Tuđman

- Daughter: Nevenka Tuđman (born in 1951)

Honours and Decorations

Croatian

Awarded by the Croatian Parliament in 1995:

| Award or decoration | |

|---|---|

| Grand Order of King Tomislav | |

| Grand Order of King Petar Krešimir IV | |

| Order of Duke Domagoj | |

| Order of Ante Starčević | |

| Order of Stjepan Radić | |

| Order of Danica Hrvatska with the face of Ruđer Bošković | |

| Order of the Croatian Trefoil | |

| Homeland War Memorial Medal | |

| Homeland's Gratitude Medal | |

Military Rank

| Award or decoration | |

|---|---|

|

Vrhovnik of the Croatian Armed Forces |

International

| Award or decoration | Country | Awarded by | Date | Place | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knight Grand Cross of the Military Order of Italy | Francesco Cossiga | 17 January 1992 | Zagreb | ||

| Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of Chile | Eduardo Frei Ruiz-Tagle | 29 November 1994 | Santiago de Chile | ||

|

Collar of the Order of the Liberator San Martin | Carlos Menem | 1 December 1994 | Buenos Aires | |

| Medal of Zhukov | Boris Yeltsin | 4 November 1996 | Zagreb | ||

| Grand Cross of the Order of the Redeemer | Konstantinos Stephanopoulos | 23 November 1998 | Athens | ||

| Order of the State of Republic of Turkey | Suleyman Demirel | 1999 | Zagreb | ||

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Franjo Tuđman para niños

In Spanish: Franjo Tuđman para niños