Boris Yeltsin facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Boris Yeltsin

|

|

|---|---|

| Борис Ельцин | |

Official portrait, c. 1991–1994

|

|

| President of Russia | |

| In office 10 July 1991 – 31 December 1999 |

|

| Prime Minister |

|

| Vice President | Alexander Rutskoy (1991–1993) |

| Preceded by | Office established Himself as Chairman of the Supreme Soviet |

| Succeeded by | Vladimir Putin |

| Chairman of the Supreme Soviet of the Russian SFSR | |

| In office 29 May 1990 – 10 July 1991 |

|

| Preceded by | Office established Vitaly Vorotnikov (as chairman of the Presidium) |

| Succeeded by | Ruslan Khasbulatov |

| First Secretary of the Moscow City Party Committee | |

| In office 23 December 1985 – 11 November 1987 |

|

| Preceded by | Viktor Grishin |

| Succeeded by | Lev Zaykov |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin

1 February 1931 Butka, Ural Oblast, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Died | 23 April 2007 (aged 76) Moscow, Russia |

| Resting place | Novodevichy Cemetery, Moscow |

| Nationality | Soviet (1931–1991), Russian (1991-2007) |

| Political party | Independent (after 1990) |

| Other political affiliations |

CPSU (1961–1990) |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 2, including Tatyana Yumasheva |

| Alma mater | Ural State Technical University |

| Signature | |

|

Central institution membership

1986–1988: Candidate member, 26th, 27th Politburo

1985–1986: Member, 26th Secretariat 1981–1990: Full member, 26th, 27th Central Committee Other offices held

1992: Minister, Defence

1976–1985: First Secretary, Sverdlovsk Regional Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union |

|

Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin (Russian: Борис Николаевич Ельцин; 1 February 1931 – 23 April 2007) was a very important Russian politician. He became the first president of Russia and served from 1991 to 1999. Before that, he was a member of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union for many years. Later, he became an independent politician. Many people saw him as someone who supported liberal ideas and Russian nationalism.

Yeltsin was born in a village called Butka in the Ural Oblast. He spent his childhood in Kazan and Berezniki. After studying at the Ural State Technical University, he worked in construction. He joined the Communist Party and slowly moved up the ranks. In 1976, he became the First Secretary of the party's committee in Sverdlovsk Oblast.

At first, Yeltsin supported the perestroika reforms of Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev. But he later felt these reforms were too slow. He wanted Russia to become a multi-party democracy. In 1987, he was the first person to ever resign from the powerful Politburo of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. This made him popular as someone who stood up against the system.

In 1990, he was elected to lead the Russian Supreme Soviet. Then, in 1991, he was elected president of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR). Yeltsin worked with leaders from other parts of the Soviet Union. He played a big role in the Soviet Union breaking apart in December 1991. After the Soviet Union dissolved, the RSFSR became the independent country of Russia. Yeltsin stayed on as president. He was reelected in 1996, though some critics said that election had problems.

As president, Yeltsin changed Russia's command economy (where the government controls everything) into a market economy (where businesses are mostly private). He did this by using "economic shock therapy", which meant making big changes very quickly. This included letting the ruble's value be set by the market, selling off many state-owned businesses (nationwide privatization), and removing price controls. These changes led to economic ups and downs and high inflation.

During this time, a small group of very rich people, called oligarchs, gained control of much of Russia's wealth. In 1993, there was a crisis when Yeltsin tried to dissolve the Russian parliament. This led to parliament trying to remove him. The crisis ended when troops loyal to Yeltsin took control of the parliament building. After this, he introduced a new constitution that gave the president much more power.

Between 1994 and 1999, there were conflicts in the Russian Caucasus, leading to the First Chechen War, War of Dagestan, and Second Chechen War. On the world stage, Yeltsin worked to improve relations with Europe and signed arms control agreements with the United States. Facing pressure at home, he resigned at the end of 1999. He chose Vladimir Putin to be his successor, who had been his prime minister for a few months. Yeltsin mostly stayed out of public life after leaving office. He had a state funeral when he died in 2007.

At first, Yeltsin was very popular in the late 1980s and early 1990s. However, his reputation suffered because of the economic and political problems during his time as president. When he left office, many Russians were not happy with him. People have both praised and criticized him. He is remembered for helping to break up the Soviet Union, bringing democracy to Russia, and introducing new freedoms. But he was also blamed for economic problems, corruption, and for weakening Russia's position as a world power.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Childhood Years: 1931–1948

Boris Yeltsin was born on 1 February 1931 in the village of Butka, in what was then the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic. This was one of the republics of the Soviet Union. His family had lived in the Urals region for a long time. His father, Nikolai Yeltsin, married his mother, Klavdiya Vasilyevna Starygina, in 1928. Boris felt closer to his mother, as his father sometimes used violence.

At that time, Joseph Stalin was the dictator of the Soviet Union. The country was a one-party state ruled by the Communist Party. In the late 1920s, Stalin's government started taking over farms and forcing people to join collective farms. Yeltsin's grandfather, Ignatii, was a successful farmer. He was accused of being a "kulak" (a rich peasant) in 1930. His farm was taken away, and his family had to move to a small cottage. Ignatii and his wife were later sent away in 1934, and he died two years later.

As a baby, Yeltsin was baptized in the Russian Orthodox Church. His mother was very religious. In the years after he was born, there was a big famine. Yeltsin was often hungry during his childhood. In 1932, his parents moved to Kazan. In 1934, his father, Nikolai, was arrested by the state security services. He was accused of speaking against the Soviet government and sent to a labor camp for three years. Yeltsin and his mother had to leave their home and stay with friends. His mother worked in a clothing factory.

In October 1936, Nikolai returned. In July 1937, Boris's brother, Mikhail, was born. That month, the family moved to Berezniki. There, Nikolai worked on a potash project. In July 1944, their sister, Valentina, was born.

Boris went to primary school in Berezniki from 1939 to 1945. He was a good student and was often chosen as class monitor. He also joined youth groups like the Komsomol. This was during World War II, and his uncle, Andrian, died fighting in the Red Army.

From 1945 to 1949, Yeltsin went to secondary school. He continued to do well in his studies. He became very interested in sports and was the captain of his school's volleyball team. He enjoyed playing pranks. Once, he played with a grenade, which accidentally blew off his thumb and index finger on his left hand. He also enjoyed long walking trips with friends in the nearby forests.

University and Early Career in Construction: 1949–1960

In September 1949, Yeltsin started studying at the Ural Polytechnic Institute (UPI) in Sverdlovsk. He studied industrial and civil engineering. This included subjects like math, physics, and drafting. He also had to study Communist ideas and a language. He chose German but never became good at it. His tuition was free, and he received a small allowance. He earned extra money by unloading railway trucks.

He got good grades in university. In 1952, he had to take a break because he got sick with tonsillitis and rheumatic fever. He spent a lot of time on athletics and joined the UPI volleyball team. He avoided joining any political groups while at university. During his summer break in 1953, he traveled across the Soviet Union, often by hitchhiking on freight trains. At UPI, he met Naina Iosifovna Girina, a fellow student who later became his wife. Yeltsin finished his studies in June 1955.

After university, Yeltsin was assigned to work in construction in Sverdlovsk. He asked to spend his first year learning different building jobs. He quickly moved up in the company. In June 1956, he became a foreman. In June 1957, he was promoted to work superintendent. In these roles, he faced challenges like unmotivated workers and a lack of building materials. He started fining people who damaged or stole materials and watched productivity closely. His work on a textile factory, where he managed 1000 workers, earned him recognition. In June 1958, he became a senior work superintendent. In January 1960, he was made head engineer of Construction Directorate Number 13.

At the same time, Yeltsin's family grew. In September 1956, he married Naina. She worked at a research institute for 29 years. Their first daughter, Yelena, was born in August 1957. Their second daughter, Tatyana, was born in January 1960. During this time, they moved to several different apartments. For family holidays, Yeltsin took his family to a lake in northern Russia and to the Black Sea coast.

Career in the Communist Party

Early Membership: 1960–1975

In March 1960, Yeltsin became a trial member of the Communist Party. He became a full member in March 1961. He later said he joined because he believed in the party's ideals. However, he also said that joining was necessary to advance his career. His career continued to grow in the early 1960s. In February 1962, he became the chief of the construction directorate. In June 1963, Yeltsin was moved to the Sverdlovsk House-Building Combine as its head engineer. In December 1965, he became the combine's director. During this time, he mostly built homes, which was a big priority for the government. He became known as a hard worker who met targets. He was even considered for a high award, the Order of Lenin. However, this was canceled after a five-story building he was constructing collapsed in March 1966. An investigation found he was not at fault.

Within the local Communist Party, Yeltsin gained a supporter in Yakov Ryabov. Ryabov became the first secretary of the party in 1963. In April 1968, Ryabov brought Yeltsin into the regional party organization. Yeltsin got a job in the construction department, even though some people thought he hadn't been a party member long enough. That year, Yeltsin and his family moved into a four-room apartment in Sverdlovsk. Yeltsin then received another award, the Order of the Red Banner of Labor, for his work on a steel mill. In the late 1960s, Yeltsin was allowed to visit France, his first trip to the West. In 1975, Yeltsin became one of the five secretaries in the Sverdlovsk Oblast. This meant he was in charge of construction, forests, and paper industries in the region. Also in 1975, his family moved to a new flat.

First Secretary of Sverdlovsk Oblast: 1976–1985

In October 1976, Ryabov was promoted and moved to Moscow. He suggested that Yeltsin take his place as the First Secretary of the Party Committee in Sverdlovsk Oblast. Leonid Brezhnev, who was the leader of the Soviet Union at the time, interviewed Yeltsin. Brezhnev agreed that Yeltsin was a good choice. The Sverdlovsk committee then voted to appoint Yeltsin. This made him one of the youngest provincial leaders in Russia, and he gained a lot of power in the region.

Yeltsin tried to improve life for people in the province. He believed it would make workers more productive. Under his leadership, new construction projects started in Sverdlovsk city. These included a subway system, new housing, theaters, a circus, and renovations to the opera house. In September 1977, Yeltsin followed orders to tear down the Ipatiev House. This was the place where the Romanov royal family had been killed in 1918. The government worried it was attracting too much attention. Yeltsin was also responsible for punishing people who wrote or published things the Soviet government considered harmful.

Yeltsin was part of the military leadership in the Urals and attended military exercises. In October 1978, the Ministry of Defense gave him the rank of colonel. In 1978, Yeltsin was also elected to the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union. In 1979, Yeltsin and his family moved into a five-room apartment in Sverdlovsk. In February 1981, Yeltsin gave a speech at a big Communist Party meeting. He was chosen to join the Communist Party Central Committee.

Yeltsin's reports at party meetings followed the rules of the time. He played along with the personality cult around Brezhnev, but he privately disliked Brezhnev's vanity. He later claimed he stopped plans for a Brezhnev museum in Sverdlovsk. While First Secretary, his views began to change. He read many journals and even an illegal copy of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's The Gulag Archipelago. He started to worry that the Soviet system was becoming less effective. He also thought about Russia's place within the Soviet Union, as Russia didn't have as much freedom as other republics.

By 1980, Yeltsin started visiting factories, shops, and public transport without warning. He wanted to see real life in the Soviet Union. In May 1981, he held a question-and-answer session with college students. He spoke openly about the country's problems, which was unusual. In December 1982, he gave a TV broadcast for the region, answering letters from viewers. This direct approach to the public was disliked by some party members, but the Central Committee didn't seem to mind. In 1981, he received the Order of Lenin for his work.

The next year, Brezhnev died and was replaced by Yuri Andropov, who also died soon after. Yeltsin spoke positively about Andropov. Andropov was followed by Konstantin Chernenko, another short-lived leader. After Chernenko's death, Yeltsin helped choose Mikhail Gorbachev as the new leader of the Communist Party in March 1985.

Moving to Moscow and Resignation: 1985–1987

Gorbachev wanted to reform the Soviet Union. He asked Yeltsin to meet him, seeing him as a possible ally. Yeltsin had some doubts about Gorbachev but agreed to support his reforms. In April 1985, Gorbachev made Yeltsin the Head of the Construction Department of the Party's Central Committee. Yeltsin was not happy with this, as he saw it as a step down, even though it meant moving to Moscow. He was given an apartment in Moscow, where his daughter Tatyana, her son, and husband soon joined him and his wife.

Gorbachev soon promoted Yeltsin to secretary of the Central Committee for construction. This was a powerful position. In December 1985, Yeltsin became the first secretary of the Moscow gorkom of the CPSU. He was now in charge of managing Moscow, a city with 8.7 million people. In February 1986, Yeltsin became a candidate (non-voting) member of the Politburo. He then focused on his role in Moscow. Over the next year, he replaced many older officials with younger people.

In August 1986, Yeltsin gave a two-hour report where he spoke openly about Moscow's problems, including issues that were usually kept secret. Gorbachev called his speech a "strong fresh wind." Yeltsin shared similar messages in other speeches, talking about the need for change.

On 10 September 1987, after being criticized by a hard-line official named Yegor Ligachyov, Yeltsin wrote a letter of resignation to Gorbachev. Gorbachev was on holiday and was surprised. No one in Soviet history had ever resigned from the Politburo voluntarily. Gorbachev called Yeltsin and asked him to change his mind.

On 27 October 1987, at a meeting of the Communist Party's Central Committee, Yeltsin spoke up. He was frustrated that Gorbachev had not addressed his concerns. He talked about the slow pace of reform, the excessive praise given to the general secretary, and the opposition he faced from Ligachyov. He then asked to resign from the Politburo. This was a shocking moment, as no one had ever spoken to a party leader like that in front of the Central Committee since the 1920s. Gorbachev accused Yeltsin of being "politically immature." No one in the Central Committee supported Yeltsin.

News of Yeltsin's actions quickly spread. Rumors of his "secret speech" made him popular as a rebel figure. Gorbachev called another meeting on 11 November 1987 to officially remove Yeltsin from his Moscow leadership role. Yeltsin was criticized by party members before being fired.

Yeltsin was given a less important job. In February 1988, he was removed from the Politburo. He felt upset and humiliated, but he started planning his return. His chance came when Gorbachev created the Congress of People's Deputies. Yeltsin began to strongly criticize Gorbachev, saying that reforms in the Soviet Union were too slow.

Yeltsin's criticism led to a campaign against him. People used examples of his awkward behavior to try and discredit him. At a party conference in 1988, Yegor Ligachyov famously told him, "Boris, you are wrong."

Despite this, on 26 March 1989, Yeltsin was elected to the Congress of People's Deputies of the Soviet Union with a huge 92% of the vote from Moscow. On 29 May 1989, he was elected to a seat on the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union. On 19 July 1989, Yeltsin announced a new group in the Congress called the Inter-Regional Group of Deputies. This group wanted radical reforms. On 29 July 1989, he was chosen as one of its five leaders.

On 16 September 1989, Yeltsin visited a grocery store in Texas, USA. A close associate later said that Yeltsin was deeply affected by seeing how much better stocked American stores were. He reportedly said, "What have they done to our poor people?" He felt pain for his country, which was so rich but exhausted. He believed they had "committed a crime against our people" by making their living standard so much lower than Americans. Some say this moment made him fully turn away from Communist ideas. In his autobiography, Yeltsin hinted that he wanted to open his own grocery stores in Russia to help solve the country's problems.

President of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic

On 4 March 1990, Yeltsin was elected to the Congress of People's Deputies of Russia from Sverdlovsk with 72% of the vote. On 29 May 1990, he was elected chairman of the Supreme Soviet of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR). Gorbachev had personally asked the Russian deputies not to choose Yeltsin. However, Yeltsin was supported by both democratic and conservative members who wanted more power for Russia.

This was part of a struggle for power between the Soviet Union's central government and the RSFSR. To gain more power, on 12 June 1990, the Russian Congress declared its sovereignty (its right to rule itself). On 12 July 1990, Yeltsin dramatically resigned from the Communist Party during a big meeting. Some party members shouted "Shame!"

1991: Presidential Election and the Fall of the Soviet Union

In May 1991, Václav Havel invited Yeltsin to Prague. There, Yeltsin clearly condemned the Soviet intervention in Czechoslovakia in 1968. On 12 June, Yeltsin won 57% of the votes in the democratic presidential elections for the Russian republic. He defeated Gorbachev's chosen candidate, Nikolai Ryzhkov, who only got 16% of the vote. In his campaign, Yeltsin criticized the "dictatorship of the center" (Moscow's control). He did not suggest a market economy at this point. He even said he would "put his head on the railtrack" if prices increased. Yeltsin took office on 10 July.

On 18 August 1991, a coup was launched against Gorbachev by government members who opposed his reforms. Gorbachev was held in Crimea. Yeltsin quickly went to the White House of Russia (the parliament building) in Moscow to oppose the coup. He gave a famous speech from atop a tank. The White House was surrounded by the military, but many soldiers joined the people protesting. By 21 August, most of the coup leaders had fled, and Gorbachev was brought back to Moscow. Yeltsin was praised worldwide for leading the opposition to the coup.

Even though Gorbachev was back, he had lost his political power. Neither the Soviet nor the Russian government structures listened to him anymore; support had shifted to Yeltsin. By September, Gorbachev could no longer control events outside Moscow. Yeltsin took advantage of this, taking over parts of the Soviet government, ministry by ministry. On 6 November 1991, Yeltsin issued a decree banning all Communist Party activities in Russia.

In early December 1991, Ukraine voted to become independent from the Soviet Union. A week later, on 8 December, Yeltsin met with Ukrainian president Leonid Kravchuk and the leader of Belarus, Stanislav Shushkevich. In the Belavezha Accords, the three presidents declared that the Soviet Union no longer existed. They announced the creation of a new group called the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS).

Gorbachev later said that Yeltsin kept the plans for the Belovezhskaya meeting a secret. He believed the main goal was to get rid of him. Gorbachev also accused Yeltsin of ignoring the will of the people, who had voted in a referendum to keep the Soviet Union united. On 12 December, the Russian parliament approved the Belavezha Accords and canceled the 1922 Union Treaty. This meant Russia was leaving a country that no longer existed.

On 17 December, Gorbachev accepted the situation and agreed to dissolve the Soviet Union. On 24 December, the Russian Federation took the Soviet Union's seat in the United Nations. The next day, Gorbachev resigned and handed his powers to Yeltsin. On 26 December, the Soviet Union officially ceased to exist. This ended the world's first and largest Communist state. Economic ties between the former Soviet republics were severely damaged. Millions of ethnic Russians found themselves living in new, foreign countries.

Initially, Yeltsin wanted to keep the old Soviet borders. However, this meant many ethnic Russians lived in parts of northern Kazakhstan, eastern Ukraine, and areas of Estonia and Latvia.

President of the Russian Federation

First Term: 1991–1996

Big Economic Changes

Just days after the Soviet Union broke up, Yeltsin decided to start major economic reforms. Unlike Gorbachev's reforms, which aimed to improve socialism, Yeltsin's plan was to completely get rid of socialism and create a capitalist market economy. This meant turning the world's largest government-controlled economy into a free-market one. On January 1, 1992, Yeltsin and U.S. President George H. W. Bush declared the Cold War officially over.

Yeltsin also worked to improve Russia's international relations. In April 1992, he visited Prague and apologized for the Soviet intervention in Czechoslovakia in 1968. He also withdrew Russian troops from there. In November 1992, he apologized for the 1956 Soviet intervention in Hungary. He signed friendship treaties with Poland and Bulgaria in 1992.

On 2 January 1992, Yeltsin, acting as his own prime minister, allowed free foreign trade, removed price limits, and let the currency value float. He also started a policy of "macroeconomic stabilization" to control inflation. This meant very high interest rates to control the amount of money and limit credit. To balance the government's budget, Yeltsin raised taxes, cut government support for industries, and reduced welfare spending.

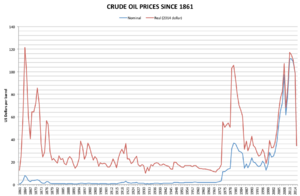

In early 1992, prices in Russia went up very quickly. Many industries closed down, leading to a long economic downturn. These reforms greatly hurt the living standards of many people, especially those who relied on government support from the Soviet era. Throughout the 1990s, Russia's economy shrank by 50%. Many parts of the economy were destroyed, and inequality and unemployment grew. People's incomes fell. Very high inflation, caused by the Central Bank of Russia's policies, wiped out many people's savings. Tens of millions of Russians became poor.

Some experts say Russia's economic problems in the 1990s were worse than the Great Depression in the United States or Germany decades earlier. Many Russian and some Western experts blamed Yeltsin's economic plan for these problems. Many politicians quickly distanced themselves from the plan. In February 1992, Russia's vice president, Alexander Rutskoy, called Yeltsin's plan "economic genocide." By 1993, the conflict over these reforms grew between Yeltsin and the parliament.

Conflict with Parliament

Throughout 1992, Yeltsin fought with the Supreme Soviet of Russia and the Congress of People's Deputies over control of the government and its policies. The speaker of the Russian Supreme Soviet, Ruslan Khasbulatov, started to oppose the reforms, even though he claimed to support Yeltsin's goals. In December 1992, the Congress of People's Deputies rejected Yeltsin's choice for Prime Minister, Yegor Gaidar. An agreement was reached that included a national vote on a new constitution.

Eventually, on 14 December, Viktor Chernomyrdin was chosen as Prime Minister. However, the conflict soon grew worse. The parliament changed its mind about holding a vote on the constitution. Yeltsin then announced on TV on 20 March 1993 that he would take "special powers" to carry out his reforms. In response, the parliament quickly tried to remove Yeltsin from the presidency on 26 March 1993. Yeltsin's opponents got over 600 votes for impeachment, but they were 72 votes short of the two-thirds needed.

During the summer of 1993, Russia had a situation of "dual power". Yeltsin and the parliament both claimed authority. For example, in July, two different governments operated in the Chelyabinsk Oblast. The parliament also made its own foreign policy decisions. In August, a newspaper wrote that "The President issues decrees as if there were no Supreme Soviet, and the Supreme Soviet suspends decrees as if there were no President."

On 21 September 1993, Yeltsin announced on TV that he was dissolving the Supreme Soviet and Congress of People's Deputies. This was against the constitution. He said he would rule by decree until new elections and a vote on a new constitution. This started the constitutional crisis of October 1993. That night, the Supreme Soviet declared Yeltsin removed from office, and Vice-President Alexander Rutskoy was sworn in as acting president.

Between 21 and 24 September, Yeltsin faced public protests. People were unhappy with the terrible living conditions under his rule. Since 1989, the economy had shrunk by half. Corruption was widespread, crime was increasing, medical services were failing, and food and fuel were scarce. Life expectancy was falling for most people. Yeltsin was increasingly blamed. By early October, Yeltsin had the support of Russia's army and police. In a large show of force, Yeltsin ordered tanks to shell the Russian White House (parliament building). The attack killed 187 people and wounded almost 500.

After the Supreme Soviet was dissolved, elections for a new parliament, the State Duma, were held in December 1993. Candidates who supported Yeltsin's economic policies lost badly. Most votes went to the Communist Party and ultra-nationalists. However, a vote held at the same time approved the new constitution. This constitution greatly increased the president's powers, giving Yeltsin the right to appoint government members, fire the prime minister, and sometimes dissolve the Duma.

Chechnya Conflict

In December 1994, Yeltsin ordered the military to invade Chechnya. He wanted to bring the republic back under Moscow's control. Nearly two years later, Yeltsin pulled federal forces out of Chechnya. This was part of a 1996 peace agreement arranged by Alexander Lebed, who was Yeltsin's security chief at the time. The peace deal gave Chechnya more self-rule but not full independence. Many in the West were upset by the decision to start the war in Chechnya.

Nuclear Alert: Norwegian Rocket Incident

In 1995, a Black Brant sounding rocket launched from Norway caused a high alert in Russia. This event is known as the Norwegian rocket incident. The Russians thought it might be a nuclear missile launched from an American submarine. This happened after the Cold War, but many Russians were still very suspicious of the United States and NATO. A full alert went up the military chain of command all the way to Yeltsin. He was notified, and the "nuclear briefcase" (used to authorize a nuclear launch) was automatically activated. Russian satellites showed that no large attack was happening, and Yeltsin agreed with his advisors that it was a false alarm.

Privatization and the Rise of "Oligarchs"

After the Soviet Union broke up, Yeltsin supported privatization. This meant selling off former state-owned businesses to private owners. The goal was to spread ownership widely and gain support for his economic reforms. In the West, privatization was seen as key to moving from Communism to a "free market." In the early 1990s, Anatoly Chubais, Yeltsin's deputy for economic policy, strongly supported privatization.

In late 1992, Yeltsin started a program of free vouchers to kick-start mass privatization. All Russian citizens received vouchers, each worth about 10,000 rubles. These could be used to buy shares in certain state businesses. However, within months, most of these vouchers ended up in the hands of a few people who bought them for cash.

In 1995, Yeltsin needed money to pay Russia's growing foreign debt. He also wanted support from Russian business leaders for his 1996 presidential election campaign. So, he started a new wave of privatization. He offered shares in some of Russia's most valuable state businesses in exchange for bank loans. This was meant to speed up privatization and give the government much-needed cash.

However, these deals basically gave away valuable state assets to a small group of powerful people in finance, industry, energy, and media. These people became known as "oligarchs" in the mid-1990s. This happened because ordinary people sold their vouchers for cash, and a small group of investors bought them up. By mid-1996, a few individuals had gained significant ownership of major companies at very low prices. Boris Berezovsky, who controlled several banks and national media, became one of Yeltsin's strongest supporters. Along with Berezovsky, people like Mikhail Khodorkovsky and Vladimir Potanin were often called Russia's oligarchs.

Korean Air Lines Flight 007

On 5 December 1991, U.S. Senator Jesse Helms wrote to Yeltsin. He asked about American servicemen who were prisoners of war (POWs) or missing in action (MIAs) from past wars. He believed some might have been held by Soviet forces.

Yeltsin responded on 15 June 1992, saying, "Our archives have shown that it is true — some of them were transferred to the territory of the USSR and were kept in labor camps... We can only surmise that some of them may still be alive." On 10 December 1991, Senator Helms also wrote to Yeltsin about Korean Air Lines Flight 007 (KAL 007). This was a passenger plane shot down by the Soviet Union in 1983. Helms asked for information about possible survivors.

One of the greatest tragedies of the Cold War was the shoot-down of the Korean Airlines Flight 007 by the Armed Forces of what was then the Soviet Union on 1 September 1983... The KAL-007 tragedy was one of the most tense incidents of the entire Cold War. However, now that relations between our two nations have improved substantially, I believe that it is time to resolve the mysteries surrounding this event. Clearing the air on this issue could help further to improve relations.

In March 1992, Yeltsin gave KAL 007's black box (without its tapes) to South Korean President Roh Tae-woo. He said, "We apologize for the tragedy and are trying to settle some unsolved issues." On 8 January 1993, Yeltsin released the tapes from KAL 007's black box (the flight data recorder and cockpit voice recorder) to the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO). For years, Soviet authorities had denied having these tapes. Yeltsin's openness about POW/MIA and KAL 007 issues showed his willingness to be more open with the West. In 1992, he also discussed biological weapons with the United States. He admitted that the Sverdlovsk anthrax leak of 2 April 1979 was caused by an accident at a military facility. The Russian government had previously said it was caused by contaminated meat.

1996 Presidential Election

In February 1996, Yeltsin announced he would run for a second term as president. This came after weeks of rumors that his political career was ending due to his health problems and low popularity. At the time, Yeltsin was recovering from several heart attacks. People also noticed his sometimes strange behavior. When campaigning began in early 1996, Yeltsin was very unpopular. Meanwhile, the opposition Communist Party had gained strength in earlier elections. Their candidate, Gennady Zyuganov, had strong support, especially in rural areas. He appealed to people's memories of the Soviet Union's past glory and order.

Yeltsin's team panicked when polls showed he couldn't win. Some advisors urged him to cancel the elections and rule as a dictator. Instead, Yeltsin changed his campaign team. He gave a key role to his daughter, Tatyana Dyachenko, and appointed Chubais as campaign manager. Chubais used his control over the privatization program to help Yeltsin's campaign.

In mid-1996, Chubais and Yeltsin got help from a few rich financial and media leaders. These "oligarchs" funded Yeltsin's campaign and made sure he got good media coverage on national TV and in major newspapers. In return, Chubais allowed these business leaders to buy large shares in some of Russia's most valuable state-owned companies. The media, led by Mikhail Lesin, presented the election as a choice between Yeltsin and a "return to totalitarianism." The oligarchs even warned of civil war if a Communist became president.

The American president, Bill Clinton, also supported Yeltsin's campaign. American advisors were sent to help Yeltsin's team with new election techniques. Several European governments also showed their support. French Prime Minister Alain Juppé and German Chancellor Helmut Kohl visited Moscow and praised Yeltsin.

Yeltsin campaigned with a lot of energy, easing concerns about his health. He stayed in the public eye. To become more popular, Yeltsin promised to stop some unpopular economic reforms, increase welfare spending, end the war in Chechnya, and pay overdue wages and pensions. He also benefited from a US$10.2 billion loan from the International Monetary Fund, which helped his government stay afloat.

Zyuganov, who didn't have Yeltsin's money or support, saw his early lead shrink. After the first round of voting on 16 June, Yeltsin appointed a popular candidate, Alexander Lebed, who finished third, as his security chief. Yeltsin then fired his defense minister and other powerful officials. In the final vote on 3 July, Yeltsin won with 53.8% of the vote, and Zyuganov got 40.7%.

Second Term: 1996–1999

Yeltsin had major heart bypass surgery in November 1996 and stayed in the hospital for months. During his presidency, Russia received US$40 billion from the International Monetary Fund and other international lenders. However, some opponents claimed that much of this money was stolen by people close to Yeltsin and put into foreign banks.

In 1998, Russia faced a big political and economic crisis. Yeltsin's government couldn't pay its debts, which caused financial markets to panic and the rouble to lose much of its value in the 1998 Russian financial crisis. During the 1999 Kosovo War, Yeltsin strongly opposed the NATO military campaign against Yugoslavia. He warned that Russia might intervene if NATO sent ground troops to Kosovo. He said, "I told NATO, the Americans, the Germans: Don't push us towards military action. Otherwise there will be a European war for sure and possibly a world war." Yeltsin stated that NATO’s bombing of Yugoslavia went against international law.

On 9 August 1999, Yeltsin fired his Prime Minister, Sergei Stepashin, and his entire government. He appointed Vladimir Putin, who was not very well known at the time, and said he wanted Putin to be his successor. In late 1999, Yeltsin and U.S. President Bill Clinton openly disagreed about the war in Chechnya. At a meeting in November, Clinton pointed his finger at Yeltsin and demanded he stop bombing attacks that were causing many civilian deaths. Yeltsin immediately left the conference.

In December, while visiting China to seek support on Chechnya, Yeltsin responded to Clinton's criticism. He said, "Yesterday, Clinton permitted himself to put pressure on Russia. It seems he has for a minute, for a second, for half a minute, forgotten that Russia has a full arsenal of nuclear weapons." Clinton dismissed Yeltsin's comments. It was up to Putin to calm things down and reassure people about U.S. and Russian relations.

Attempted Impeachment and Resignation

On 15 May 1999, Yeltsin survived another attempt to remove him from office. This time, it was by the democratic and communist opposition in the State Duma. He was accused of several unconstitutional actions. These included signing the Belovezha Accords that dissolved the Soviet Union in December 1991, his actions during the crisis in October 1993, and starting the war in Chechnya in 1994. None of these accusations received enough votes (two-thirds majority) in the Duma to start the impeachment process.

On 31 December 1999, Yeltsin gave a televised speech announcing his resignation. In his speech, he praised the new freedoms in culture, politics, and economy that his government had brought. However, he also apologized to the Russian people for "not making many of your and my dreams come true. What seemed simple to do proved to be excruciatingly difficult."

When he left office, some estimates put his approval ratings as low as 2%. Polls also suggested that most Russians were happy about Yeltsin's resignation. His first decree as president was to grant Yeltsin lifelong protection from prosecution.

Life After Resignation

After resigning, Yeltsin mostly stayed out of the public eye. He made very few public statements. In December 2000, he criticized his successor, Putin, for bringing back the tune of the Soviet-era national anthem. In January 2001, he was hospitalized for six weeks with pneumonia. On 13 September 2004, after the Beslan school hostage crisis, Putin proposed a plan to change how regional governors were chosen. Instead of being elected, they would be directly appointed by the president. Yeltsin, along with Mikhail Gorbachev, publicly criticized this plan. They said it was a step away from democracy in Russia and a return to the old Soviet system.

In September 2005, Yeltsin had hip surgery in Moscow after breaking his leg in a fall while on holiday in Italy. On 1 February 2006, Yeltsin celebrated his 75th birthday.

Death and Funeral

Boris Yeltsin died of congestive heart failure on 23 April 2007, at the age of 76. Experts said his health problems began during a visit to Jordan in late March and early April. He was buried in the Novodevichy Cemetery on 25 April 2007. Before the burial, his body was placed in the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow for people to pay their respects.

Yeltsin was the first Russian head of state in 113 years to have a church ceremony for his burial, after Emperor Alexander III. He was survived by his wife, Naina Iosifovna Yeltsina, whom he married in 1956, and their two daughters, Yelena and Tatyana.

President Putin declared the day of his funeral a national day of mourning. Flags were flown at half-staff, and all entertainment programs were canceled for the day.

Beliefs and Personality

What Yeltsin Believed In

During the late Soviet period, Yeltsin's ideas about the world began to change. He started to believe in populism and a non-ethnic Russian identity. In the late 1980s, Yeltsin told a Greek newspaper that he saw himself as a "social democrat." He added that "Those who still believe in communism are moving in the sphere of fantasy."

Yeltsin is linked to "liberal Russian nationalism." He played a key role in how Russian nationalism developed. He helped guide Russian national feelings in a way that avoided conflicts with other national groups in the Soviet Union. As the head of the Russian SFSR, he emphasized Russia's specific interests within the larger Soviet Union. Some compared Yeltsin's move away from the Soviet Union's "empire-building" to the ideas of writer Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. Solzhenitsyn had called for Russia to leave the Soviet Union. However, by 1990, Yeltsin still seemed to believe that Ukrainians and Belarusians, who are also East Slavs, would want to stay united with Russia. By 1991, it was clear this would not happen, as Ukraine wanted full independence. During his presidency, he increasingly showed concern for ethnic Russians living in neighboring countries.

Personal Traits

Yeltsin was described as a complex person. He had a logical mind but also loved adventure. He was good at understanding situations as a whole. He could be stubborn and restless. In his autobiography, Yeltsin seemed to see himself more as a Soviet person than a Russian. Throughout his life, Yeltsin had several health problems, which he usually tried to hide. As a child, he broke his nose and injured his hand, which he was self-conscious about. He was also deaf in his right ear. Although his mother was a religious Orthodox Christian, Yeltsin did not grow up practicing. He only became religious in the 1980s and 1990s.

Yeltsin said his "style of management" was "tough." He "demanded strict discipline and fulfillment of promises." He was a workaholic. At university, he got into the habit of sleeping only four hours a night. He was punctual and very strict about his subordinates being on time. He had an excellent memory and loved reading. By 1985, his family had about 6000 books. At university, he was known for playing practical jokes. He enjoyed listening to folk songs and pop music. He could also play the lozhki (spoons). Until his health declined in the 1990s, Yeltsin enjoyed swimming in icy water. He started each day with a cold shower. He also loved using the banya (steam bath). Yeltsin enjoyed hunting and had his own collection of hunting guns. He liked to give watches and other gifts to his employees, often to motivate them. He disliked swearing. When he was frustrated or angry, he would often snap pencils in his hand.

Yeltsin's favorite writer was Anton Chekhov, but he also enjoyed the work of Sergei Yesenin and Alexander Pushkin. He was described as having a "husky baritone" voice.

Some people saw Yeltsin as a "hero for young Russians." He was seen as a popular figure for those who were tired of the Brezhnev years. He was described as cheerful and open, and also charismatic. He presented himself as a "true working-class hero" when he challenged the Soviet government.

Yeltsin had always wanted a son. His daughter Yelena briefly married a school friend, Aleksei Fefelov. They had a daughter, Yekaterina, in 1979, before separating. Yelena then married an Aeroflot pilot, Valerii Okulov. They had a second daughter, Mariya, in 1983. Yeltsin's other daughter, Tatyana, married Vilen Khairullin in 1980. They had a son, Boris, in 1981, named after his grandfather, but they soon separated. Tatyana then married Leonid Dyachenko. For a while, they lived with Yeltsin in his Moscow apartment. Yeltsin was loyal to his friends. He chose friends he thought were good at their jobs and had strong morals. Among his friends, Yeltsin could be very joyful and hospitable.

Honors and Awards

Russian and Soviet

- Russia: Order "For Merit to the Fatherland", 1st class (12 June 2001) – for outstanding contributions to the Russian state

- Soviet Union: Order of Lenin (January 1981) – for services to the Communist Party and Soviet state

- Soviet Union: Order of the Red Banner of Labour, twice;

- August 1971 – for services in a five-year plan

- January 1974 – for achievements in construction

- Soviet Union: Order of the Badge of Honour (1966) – for achievements in construction

- Russia: Medal "In Commemoration of the 1000th Anniversary of Kazan" (2006)

- Soviet Union: Jubilee Medal "In Commemoration of the 100th Anniversary of the Birth of Vladimir Ilyich Lenin" (November 1969)

- Soviet Union: Jubilee Medal "Thirty Years of Victory in the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945" (April 1975)

- Soviet Union: Jubilee Medal "60 Years of the Armed Forces of the USSR" (January 1978)

- Soviet Union: Gold Medal, Exhibition of Economic Achievements (October 1981)

- Russia: Medal – "In memory of the army as a volunteer" (March 2012, posthumous) – for contributions to remembering the Great Patriotic War

Foreign Awards

- Belarus: Order of Francysk Skaryna (31 December 1999) – for developing Belarusian-Russian cooperation

- Kazakhstan: Order of the Golden Eagle (1997)

- Ukraine: Order of Prince Yaroslav the Wise, 1st class (22 January 2000) – for developing Ukrainian-Russian cooperation

- Italy: Knight Grand Cross with collar of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic (1991)

- Latvia: Order of the Three Stars, 1st class (2006)

- Palestine: Order "Bethlehem 2000" (2000)

- France: Knight Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour (France)

- South Africa: Order of Good Hope, 1st class (1999)

- Lithuania: Medal of 13 January (9 January 1992)

- Lithuania: Grand Cross of the Order of the Cross of Vytis (10 June 2011, posthumous)

- Mongolia: Order "For Personal Courage" (18 October 2001)

Other Awards

- Russia: Gorchakov Commemorative Medal (Russian Foreign Ministry, 1998)

- International Olympic Committee: Golden Olympic Order (International Olympic Committee, 1993)

Religious Awards

- Russia: Order of Saint Blessed Grand Prince Dmitry Donskoy, 1st class (Russian Orthodox Church, 2006)

- Greece: Chevalier of the Order of the Chain of the Holy Sepulchre (Greek Orthodox Church of Jerusalem, 2000)

Titles

- Honorary Citizen of

- Russia: Sverdlovsk Oblast (2010, posthumous)

- Russia: Kazan (2005)

- Russia: Samara Oblast (2006)

- Armenia: Yerevan (2002)

- Turkmenistan: Turkmenistan (1993)

- Greece: Corfu (1994)

Images for kids

See Also

In Spanish: Borís Yeltsin para niños

In Spanish: Borís Yeltsin para niños

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |