Roger Joseph Boscovich facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Roger Joseph Boscovich

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait by Robert Edge Pine, London, 1760.

|

|

| Born |

Ruđer Josip Bošković

18 May 1711 |

| Died | 13 February 1787 (aged 75) |

| Citizenship | Republic of Ragusa |

| Alma mater | Collegio Romano |

| Known for | Precursor of the atomic theory Founder of Brera Observatory |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Theology, physics, astronomy, mathematics, natural philosophy, diplomacy, poetry |

| Institutions | Brera Observatory University of Pavia |

| Influences | G. W. Leibniz |

Roger Joseph Boscovich (born Ruđer Josip Bošković; 18 May 1711 – 13 February 1787) was a brilliant scientist and thinker from the Republic of Ragusa (today Dubrovnik, Croatia). He was a physicist, astronomer, mathematician, and philosopher. He was also a Jesuit priest and a polymath, meaning he was an expert in many different subjects.

Boscovich lived and studied in Italy and France. He made important discoveries, including an early idea of atomic theory. He also helped develop ways to figure out a planet's orbit and rotation using observations. In 1753, he discovered that the Moon has no atmosphere.

Contents

Biography

Early Life and Education

Ruđer Josip Bošković was born in Dubrovnik on 18 May 1711. His mother, Paola Bettera, came from an Italian noble family. His father, Nikola Bošković, was a merchant from Ragusa. Ruđer was the seventh of his family's eight children.

When he was about 8 or 9 years old, Ruđer started school at the local Jesuit Collegium Ragusinum. He was a very bright student with a great memory.

In 1725, at age 14, Ruđer left Dubrovnik for Rome. He joined the Society of Jesus, which was famous for its schools. He studied mathematics and physics and showed great talent. By 1740, he became a professor of mathematics at the college. He was known for understanding new scientific ideas and for his clear way of explaining things.

Scientific Discoveries and Travels

Even with his teaching duties, Boscovich found time to research many areas of science. He published many papers on topics like the transit of Mercury, the Aurora Borealis, the shape of the Earth, and the theory of comets.

In 1742, Pope Benedict XIV asked Boscovich and other scientists for advice. A crack had appeared in the dome of St. Peter's Basilica in Rome. Boscovich suggested adding five iron bands around the dome to make it stable. His idea was used.

In 1744, he became a Roman Catholic priest. In 1745, he wrote De Viribus Vivis. In this book, he tried to connect Isaac Newton's ideas about gravity with Gottfried Leibniz's ideas about tiny "monad-points." He developed the idea of "impenetrability" to explain how hard objects behave.

Boscovich visited his hometown of Dubrovnik only once in 1747. He never returned after that. He helped measure a section of the Earth's surface in Italy with another Jesuit, Christopher Maire. This project, which started in 1750, helped create a detailed map of the Papal States.

In 1757, Boscovich used his diplomatic skills. He helped settle a dispute between the Grand Duke of Tuscany and the Republic of Lucca over a lake.

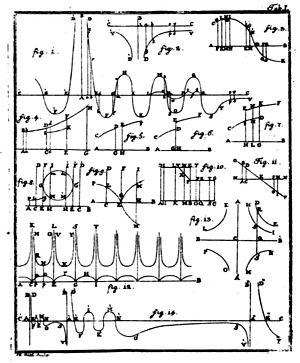

In 1758, he published his most famous work, Philosophiæ naturalis theoria (Theory of Natural Philosophy). This book contained his atomic theory and his ideas about forces. It was reprinted several times.

In 1760, Boscovich went to London as an ambassador for Dubrovnik. The British government thought Dubrovnik was helping France in a war. Boscovich successfully proved that Dubrovnik was neutral. While in England, he became a member of the Royal Society.

In 1761, he traveled to Constantinople to observe the transit of Venus across the Sun. He then went to Saint Petersburg in Russia, where he became a member of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

Later Years and Legacy

In 1764, Boscovich became a professor of mathematics at the University of Pavia in Italy. He also directed the Brera Astronomical Observatory in Milan for six years.

He was invited to go to California to observe another transit of Venus in 1769. However, the Spanish government had recently expelled Jesuits, so he could not go. Boscovich often had to move because of disagreements with others.

In 1773, his Jesuit order was shut down in Italy. He then accepted an invitation from the King of France to move to Paris. There, he became the director of optics for the navy. He stayed in France for ten years, continuing his scientific work. He published important works on micrometres and achromatic telescopes.

In 1783, he returned to Italy. He published a five-volume collection of his works on optics and astronomy in 1785. His health began to fail, and he died in Milan on 13 February 1787. He was buried in the church of St. Maria Podone.

Boscovich's Idea of Determinism

Boscovich had an interesting idea about how the universe works, which is similar to what is known as Laplace's demon. He thought that if you knew the exact position and speed of every tiny particle in the universe, you could figure out everything that happened in the past and everything that will happen in the future.

He believed that forces in nature change smoothly, without sudden jumps. This idea of continuous force was important for his theory. Modern science, especially quantum mechanics, suggests that knowing everything about a particle's position and speed at the same time is not possible.

Further Works

Besides his major books, Boscovich also wrote textbooks for his students. He published accounts of his travels, including a journey from Constantinople to Poland.

He also worked on practical engineering projects. These included advising on repairs for St. Peter's Basilica and the Duomo of Milan. He also wrote reports on damage to buildings in Rome caused by a whirlwind.

Legacy

Boscovich's contributions to astronomy were so important that a crater on the Moon was named after him: Boscovich crater.

The largest science institute in Croatia, located in Zagreb, is called the "Ruđer Bošković Institute". In 1782, Boscovich helped start the National Association of the Sciences in Italy, which brought together important Italian scientists. The oldest astronomical society in the Balkans, in Belgrade, Serbia, is named the Astronomical Society Ruđer Bošković.

His ideas, especially his Theory of Natural Philosophy, influenced later thinkers. For example, the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche was inspired by Boscovich's ideas about force.

Religious Views

Roger Joseph Boscovich was a Roman Catholic priest. He was open about his religious beliefs. In his famous book A Theory of Natural Philosophy, he wrote that his theory helped show the need to believe in a Divine Creator. He felt it proved that the world was not created by accident.

Boscovich also wrote poetry, often including religious and astronomical themes. He wrote verses about the Virgin Mary. He even worked as a confessor in the dome of St. Peter's Basilica, the same dome he helped save from ruin.

Nationality and Identity

The idea of "nationality" based on language or culture is a modern concept. Because of this, it can be hard to assign a single nationality to people from past centuries, especially those from areas with mixed cultures like Dubrovnik.

Boscovich's legacy is celebrated in Croatia, Italy, and Serbia. He had connections to all these cultures.

- Croatian Identity: Some sources say he spoke of his Croatian identity. He wrote to his sister that he had not forgotten the Croatian language. In a letter from 1757, he cheered for "our Croats" after meeting Croatian soldiers.

- Italian Connections: His mother's family came from Italy, and he spent most of his life there. He often used the Italian language in his personal letters. Some encyclopedias describe him as an Italian scientist.

- Serbian Connections: The Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts includes him among important Serbs.

Boscovich himself was proud of his Dalmatian identity. When a French mathematician called him "an Italian mathematician," Boscovich replied that he was "a Dalmatian from Dubrovnik, and not an Italian." However, he added that since he had lived in Italy for a long time, he could "in some way be called Italian."

Works

Boscovich published many scientific papers and books throughout his life. Here are a few examples of his important works:

- De maculis solaribus (1736) – On Sunspots

- De aurora boreali (1738) – On the Aurora Borealis

- Dissertatio de telluris figura (1739) – A Dissertation on the Shape of the Earth

- De viribus vivis (1745) – On Living Forces

- De cometis (1746) – On Comets

- De lunae atmosphaera (1753) – On the Atmosphere of the Moon

- Theoria philosophiae naturalis (1758) – A Theory of Natural Philosophy

- De Solis ac Lunae defectibus (1760) – On the Sun, Moon, and Eclipses

- Opera pertinentia ad opticam et astronomiam (1785) – Works Pertaining to Optics and Astronomy

See also

In Spanish: Ruđer Bošković para niños

In Spanish: Ruđer Bošković para niños

- List of Catholic clergy scientists

- Pietro De Martino

- Quantile regression

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |